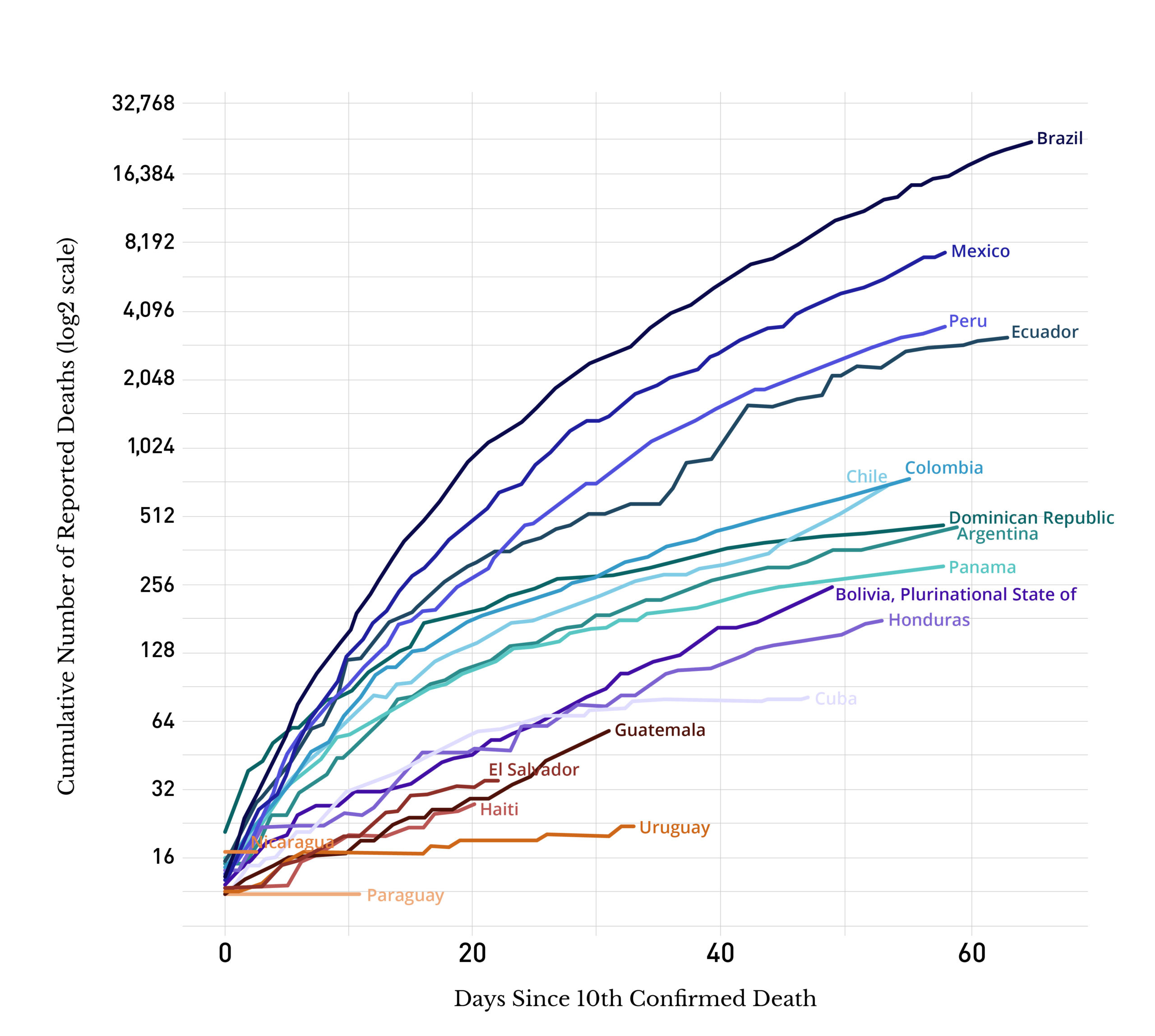

Brazil identified its first Covid-19 case on February 26. Since then, the virus has spread across Latin America with varying epidemiological trajectories as reflected by the death rates in Figure 1 to the point that the World Health Organization (WHO) has just declared Latin America the epicenter of the pandemic. Less noticed have been its widespread consequences for democratic governance across a region already facing crucial governability challenges before the pandemic. Whereas Covid-19 provided a popularity boost for many Latin American presidents who acted rapidly and decisively, it also limited crucial mechanisms of democratic accountability, such as elections and protests. Additionally, the need for coordination across territorial jurisdictions to avoid contagion has highlighted the limitations of federal systems and the weakness of Latin American states in a region where half of the labor force works in the informal sector. Once the pandemic recedes, the consequences of Covid-19 are likely to increase popular discontent, highlighting the urgent need to expand and renovate mechanisms for democratic accountability in the region.

Democratic accountability in Latin America

After a year of citizen disaffection, which had resulted in widespread protests as well as electoral turnover in various presidential elections, Covid-19 arrived on Latin American shores.1Maria Victoria Murillo, “Why Is South America in Turmoil? An Overview,” Americas Quarterly, November 18, 2019. The virus immediately impacted two crucial mechanisms of democratic accountability: elections and mobilization. The salience of these effects was particularly noticeable because Latin America had closed 2019 amidst a wave of protests and political crises.

The outburst of popular discontent in Latin America was triggered by an economic slowdown, which reversed prior gains in social mobility and inequality reduction.2Nora Lustig, “Desigualdad y descontento social en América Latina,” Nueva Sociedad no. 286 (March–April 2020): 53–61. This situation was compounded by corruption and institutional scandals, further undermining popular support for democracy.3Elizabeth J. Zechmeister and Noam Lupu, eds., Pulse of Democracy (Nashville, TN: LAPOP, 2019). Among the many countries where social discontent overflowed into the streets, Chile and Bolivia stood out. Chile, often touted for its sustained economic growth, experienced unending protests that brought ten percent of its population to the streets, with mobilizations continuing into early March 2020. Student mobilizations originally denounced an increase in transportation prices by a right-wing government. Over time, students were joined by broad swaths of the population and demands shifted to question the legitimacy of a constitution inherited from the military dictatorship. In Bolivia, the opposition protested against the results of the presidential election. Left-wing president Evo Morales was running for re-election despite having lost a plebiscite asking to end the constitutional ban on doing so. As the police joined the revolt and the military demanded his resignation, Morales was forced into exile, triggering a questionable succession and further protests by his followers, who were violently repressed.

In both Chile and Bolivia, electoral solutions seemed the only way out of deep political crises that polarized those societies. Yet the arrival of Covid-19 forced the suspension of the Chilean plebiscite on constitutional reform scheduled for April 2020 and of the new Bolivian presidential elections of May 2020. Without an institutional solution and with protests restrained by fear of contagion, quarantines, and curfews—and even a biased application of those regulations as denounced by Human Rights Watch for Bolivia—popular discontent is left with no clear outlet, signaling a deeper regional problem with political accountability.

“With no mechanisms for mail-in voting or effective alternatives to protests for demanding policy change, Latin American citizens are suddenly deprived of their main two mechanisms of democratic accountability.”The suspension of elections spread throughout the region as Uruguay, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, and Paraguay plan to postpone local elections and many other countries rescheduled special elections.4María Victoria Murillo, “Covid-19: Political Impact in Latin America,” (commentary on dataset by Andrea Quijano, Institute of Latin American Studies, Columbia University, May 1, 2020). Social protests were restrained by the virus, and social media does not provide a real alternative for many groups as it is accessible mostly to the more educated and younger population, and it often reinforces echo chambers rather than amplifying popular support. Social media cannot replace social mobilization, such as the 2019 Indigenous marches in Ecuador to protest gas prices, stopped the country, and forced the president to relocate outside the capital city. With no mechanisms for mail-in voting or effective alternatives to protests for demanding policy change, Latin American citizens are suddenly deprived of their main two mechanisms of democratic accountability.

Growing internal disconnections

Democratic governance was also affected by intragovernmental tensions produced by the need for coordination across jurisdictional units to avoid contagion. Indeed, the three large Latin American federal countries were all pushed by subnational authorities who moved earlier to declare measures of social isolation. Yet, whereas the Argentine president soon followed suit in declaring a national quarantine and coordinated with both allied and opposition provincial governors, the outsider presidents of Mexico and Brazil were reticent to admit the health risks of Covid-19.

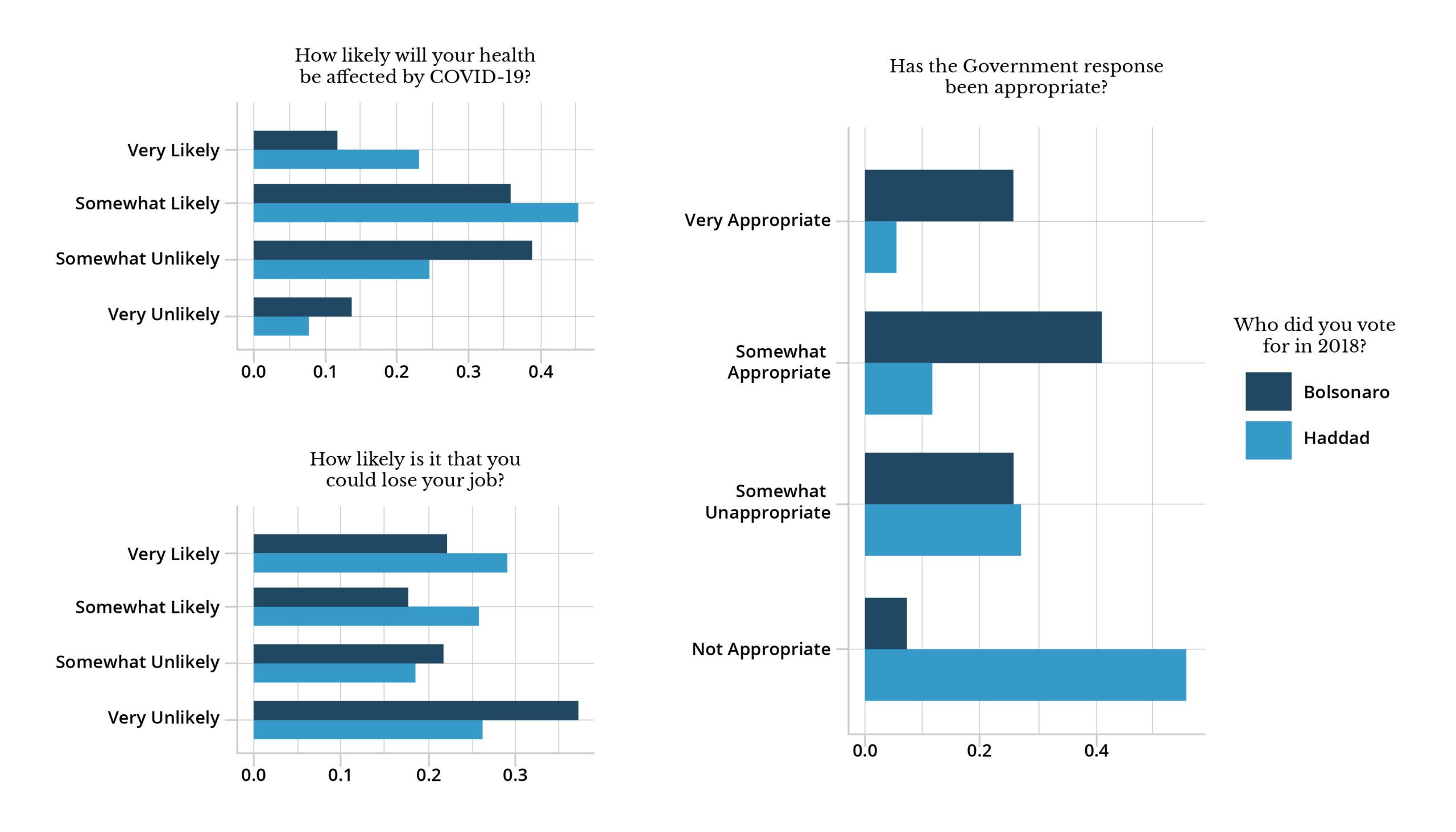

The Mexican president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, imposed voluntary measures of social isolation, pushed by a decline in his popularity, but some states imposed more stringent quarantines. Whereas compensation policies at the federal level were limited (and its figures on the deaths questioned), some governors were more generous in devising policies to deal with the economic costs of social isolation. These disagreements, however, paled in comparison with the almost open war between Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro and the majority of Brazilian governors (even his political allies), who followed WHO guidelines of social isolation against his will. As governors sued the president successfully to continue their quarantine policies and the Brazilian congress passed a generous compensation package for Brazil’s large informal sector, Bolsonaro continued to deny the risks of Covid-19, fired his health minister, and joined demonstrations against social isolation.5Murillo, “Covid-19: Political Impact in Latin America.” Whereas Bolsonaro’s popularity has suffered as Brazil leads the region in number of deaths (Figure 1) and is second only to the United States in the world, Brazilian public opinion is polarized around perceptions of Covid-19 to a much larger degree than public opinion in Argentina, or even in Mexico. Indeed, voter results from the 2018 presidential election are strong predictors of opinion on both the Bolsonaro government’s response to the pandemic and Covid-19’s health and economic risks, as shown by Calvo and Ventura in Figure 2.6Ernesto Calvo and Tiago Ventura, “Will I Get COVID-19: Partisanship, Social Media Frames, and Perceptions of Health Risk in Brazil” (working paper, ILCSS, University of Maryland, 2020).

Problems of intraterritorial coordination were less prevalent outside federal systems. However, Chilean mayors also imposed more stringent measures when their localities were affected—even when they shared partisan affiliations with the president. A prescient decision, as Chile’s health system is being overwhelmed by Covid-19 patients at the time I am writing. Intragovernmental conflict seems less likely for presidents whose popularity was boosted by their rapid response to the pandemic, as shown by the cases of Peru and El Salvador, where presidential popularity had reached 80 percent, or even cases that had less popular presidents before Covid-19, like those of Colombia and Costa Rica.7Murillo, “Covid-19: Political Impact in Latin America.” However, the pre-existing weakness of health systems has forced even countries with early responses and generous compensation packages for those who lost jobs, such as Peru, to ration access to treatment.

“Outsider politicians, more dependent on public support than their mainstream counterparts, seem to be straining democratic institutions amidst the pandemic, which can sway their rankings in either direction.”Presidential efforts at leading the policy response to Covid-19 may generate risks for democratic governance in either case. On the one hand, highly popular presidents, who were already uncomfortable with checks and balances, could use this popularity boost to further weaken horizontal accountability. An example may be President Nayib Bukele of El Salvador, who brought the military into congress to enforce legislative discipline in February. He has been criticized for his iron-hand application of the quarantine, his treatment of inmates in prisons during the pandemic, and more recently for declaring a state of emergency ignoring congress. On the other hand, an unpopular president like Bolsonaro, at odds with other political powers, may also generate instability given the factionalization of the Brazilian political system and the possibility of impeachment (which has ended two presidencies in the last three decades). As his ministers of health and justice resigned, Bolsonaro and his followers mobilized to call for the military to save Brazil, but the armed forces have denied any intention of intervention. In either case, outsider politicians, more dependent on public support than their mainstream counterparts, seem to be straining democratic institutions amidst the pandemic, which can sway their rankings in either direction.

Political discontent during economic uncertainty

In a region where large swaths of the population work in the informal sector and survive from day-to-day income, the quarantine’s impact may have longer lasting repercussions on democratic accountability. The slowdown of 2019 has become a full recession and the number of people in poverty is increasing daily. The vulnerability of the new middle class that emerged during the commodities boom is now evident. Since many of these countries lack robust social safety nets, the increasing precarity is likely to feed popular discontent given the economic challenges that the region will face. The effects of a sharp decline in the price of commodities—especially oil, a main export product in the region—along with the impact of Covid-19 on tourism, remittances, economic activity, and foreign investment are likely to be devastating.8Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Special Report: Dimensionar los efectos del Covid-19 para pensar la reactivacion (Chile: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2010). After the “rally around the flag” effect of the pandemic, economic conditions are likely to return to a traditional pattern where they exercise a crucial influence on presidential popularity and voting behavior, even when presidents are not always responsible for those conditions.9→María Victoria Murillo and Giancarlo Visconti, “Economic Performance and Incumbents’ Support in Latin America,” Electoral Studies 45, (February 2017): 180–190.

→Daniella Campello and Cesar Zucco, The Volatility Curse: Exogenous Shocks and Representation in Resource-Rich Democracies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming). Countries that are harder hit (economically and epidemiologically) or where the pandemic restrained prior discontent are likely to see this effect earlier. Indeed, governments with questioned legitimacy in Chile and Bolivia had to face small and focalized protests in response to the dire economic conditions of informal sector workers—although in Bolivia, demands also involved the realization of the postponed presidential elections.

Covid-19 has weakened two crucial mechanisms for democratic accountability in Latin America—elections and protests—and strengthened presidents who acted decisively and concentrated power to coordinate the response. Whereas the longer-term consequences are still uncertain, in the less democratic regimes of the region, such as Venezuela, presidents often took advantage of the crisis to increase societal control. Yet the risks of presidential centrality will heighten when the far-reaching consequences the current situation hit the economies of the region. As popular discontent cannot be channeled immediately through elections and mobilization, it may simmer, risking a future explosion. In a region characterized by compulsory voting, the lack of effective alternatives for secret and universal elections during the pandemic heightens the urgency for policy creativity to reopen avenues for political accountability that strengthen democratic governance.

Banner photo credit: Palácio do Planalto/Flickr

References:

→Daniella Campello and Cesar Zucco, The Volatility Curse: Exogenous Shocks and Representation in Resource-Rich Democracies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming).