Rep. John Lewis, the last living speaker from the 1963 March on Washington, died this summer, on July 17, 2020. His funeral was broadcast on all of the major cable television networks here in the United States. Journalists knit together elegiac newsreels to recount his early life as a student organizer in the 1950s and 1960s. While watching these tributes, it occurred to me that so much of this footage was available because of Lewis. During his lifetime, the Congressman had been masterful at persuading White journalists to visit the segregated South to cover his sit-ins and marches.1Leigh Raiford, “‘Come Let Us Build a New World Together’: SNCC and Photography of the Civil Rights Movement,” American Quarterly 59, no. 4 (2007): 1129–1157. By engaging in “archiving as digital protest,”2Subin Paul and David O. Dowling, “Digital Archiving as Social Protest: Dalit Camera and the Mobilization of India’s ‘Untouchables’,” Digital Journalism 6, no. 9 (2018): 1239–1254. Lewis had created a “subaltern counterhistory”3Stuart Davis, “Digital Archives as Subaltern Counter-Histories: Situating “Favela Tem Memoria” in the Rio de Janeiro Media and Political Landscape,” Digital Journalism 6, no. 9 (2018): 1255–1269. of the civil rights movement, which might not have existed otherwise—let alone endured as a posthumous visual testament of lifelong activism.

What footage, I wondered, would future generations have when they looked to recount the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement in May 2020? At the time of Lewis’s death, the United States was raging still, in a nearly two month-long protest to the extrajudicial killing of George Floyd. And, unlike the civil rights movement—which owed much to legacy media for its coverage—this movement’s leaders relied instead on ephemeral social media platforms to bear witness. Thus, if today’s amalgam of fortuitous smartphone witnesses and dedicated live streamers continued to upload their frontline footage to Instagram, Periscope, Snapchat, or TikTok—and if those sites disappear most of it within 24 hours, by design—then how will history remember this summer?

“What role should social media platforms play in curating and saving content for future generations of news consumers?”Three concepts are central to understanding how social scientists might intervene to prevent this coming archival crisis. I call these the “three Ps” of mobile journalism conservancy: precarity, privacy, and platforms. First, I am encouraging researchers to study how vanishing video has threatened our collective memory of the largest social justice movement in US history.4Larry Buchanan, Quoctrung Bui, and Jungal K. Patel, “Black Lives Matter May Be the Largest Movement in US History,” New York Times, July 3, 2020. At the same time, this essay is not a suggestion that media scholars begin to screenshot fleeting video for future studies without regard for a user’s privacy and safety. I want us to think about how the act of archiving protest videos can introduce a host of ethical dilemmas without a citizen journalist’s consent. Lastly, I want to engender a debate about whether a social media platform can be (or even should be) an effective newsreel. Increasingly, these sites hold the only audiovisual accounts of key protests, which may prove notable in the future. What role should social media platforms play in curating and saving content for future generations of news consumers? Taken together, these three considerations will help evolve our current appraisal of social media platforms, not only as sites for breaking news, but also as potential loci for historic preservation.5Farida Vis, “Twitter as a Reporting Tool for Breaking News: Journalists Tweeting the 2011 UK Riots,” Digital Journalism 1, no. 1 (2013): 27–47.

The rise of vanishing video

No news medium ever has been impervious to potential loss. Newspapers are susceptible to water damage. Audio files are beholden to the device “player” of the moment. Videotape is vulnerable to extreme temperatures. What is different about today’s digital video, however, is that much of it is programmed to disappear. Time-limited instant messaging services feature video uploads that are viewable only within a finite window. Snapchat launched this genre, for example, with video that vanishes after 24 hours. Early research into the platform’s ephemerality indicated that Snapchat users preferred not to seek “Instafame” with sleek visuals. They used the mobile application to share their unpolished images instead with a smaller, more intimate base of followers.6Lukasz Piwek and Adam Joinson, “‘What Do They Snapchat About?’ Patterns of Use in Time-limited Instant Messaging Service,” Computers in Human Behavior 54 (January 2016): 358–367. The platform felt more personal because of this raw content, since life’s small moments, rather than one’s full humblebrag book, were on display—if but for a day.7Joseph B. Bayer et al., “Sharing the Small Moments: Ephemeral Social Interaction on Snapchat,” Information, Communication & Society 19, no. 7 (2016): 956–977. Researchers found that Snapchat’s promise to dissolve data enabled young adults to “take up a range of discourses and demonstrate discursive agency.”8Jennifer Charteris, Sue Gregory, and Yvonne Masters, “Snapchat ‘Selfies’: The Case of Disappearing Data,” Rhetoric and Reality: Critical Perspectives on Educational Technology. Proceedings of ascilite Dunedin 2014 (2014): 389–393. Snapchat, in other words, became a destination for doodles, funny face filters, food images, and even sexting.9Nicole A. Poltash, “Snapchat and Sexting: Snapshot of Baring your Bare Essentials,” Richmond Journal of Law & Technology 19, no. 4 (Summer 2013): 1–24.

For all of these reasons, Snapchat enjoyed a meteoric rise to the top of the social media fray over a three-year period, when its base of active users grew from 10 million in mid-2012, to more than 70 million in early 2014, and 100 million in early 2015. Roughly 400 million “snaps” were uploaded to the platform daily by 2015. During the same timeframe, Facebook and Instagram combined could not beat this volume of participation. I point out this era of Snapchat’s incredible growth because it coincided with the Black Lives Matter movement’s contentious rise. At the height of the movement’s first wave, between 2014 and 2016, African Americans were using smartphones to craft counternarratives of fatal police encounters, often uploading their protest journalism to ephemeral sites like Snapchat.10Allissa V. Richardson, “Bearing Witness While Black: Theorizing African American Mobile Journalism after Ferguson,” Digital Journalism 5, no. 6 (2017): 673–698. I came to understand that three “Ps” acted upon these videos to determine whether they will vanish or endure: platform-inspired precarity, the growing consideration of protester privacy, and the platform’s in-built affordances.

Considering video precarity as power play

“In addition to baking in ephemerality by design, social media platforms make opaque editorial decisions to disappear video too—often without explanation.”The primary lens through which social scientists can regard protest journalism’s precarity is that of political economic theory. An entity can be held in a precarious state only if another, more powerful entity has the ability to give or take away its resources. With regard to ephemeral video, this means that social media platforms have garnered a lopsided advantage over marginalized groups of Black people who believe that uploading videos to its sites are the primary way to practice “sousveillance,” or looking from below. Since the Black Lives Matter movement began, African Americans have wielded their smartphones to capture excessive police force, so-called “Karen’s Gone Wild,” and many other displays of potentially deadly anti-Black racism. These citizen journalists then hijacked social media platforms to create ad hoc emergency broadcast networks. Unfortunately, these platforms have not acted as neutral parties. In addition to baking in ephemerality by design, social media platforms make opaque editorial decisions to disappear video too—often without explanation.

Perhaps the most glaring examples of this are the tragic cases of Diamond Reynolds, Korryn Gaines, and Facebook. In July 2016, Ms. Reynolds became the first person to livestream a fatal police encounter when she filmed her fiancé, Philando Castile, groaning in agony after Officer Jeronimo Yanez shot him in their car. At the time, Facebook’s CEO, Mark Zuckerberg wrote:

The images we’ve seen this week are graphic and heartbreaking, and they shine a light on the fear that millions of members of our community live with every day. While I hope we never have to see another video like Diamond’s, it reminds us why coming together to build a more open and connected world is so important—and how far we still have to go.

One month later, however, in August 2016, Korryn Gaines attempted to leverage the new technology to livestream the Baltimore County Police Department’s unlawful entry into her home. They were there to serve her with a traffic warrant. When she refused to come outside, they kicked in her door, launching an hours-long standoff. While Gaines was able to broadcast the beginning of the encounter, Facebook cut her feed eventually, at the police’s request. Then police rushed into her home and shot her fatally, wounding her five-year-old son, Kodi, in the process. This time, Zuckerberg did not release a statement about the incident. Facebook, in both cases, had the power to elevate or suppress the Black witnessing that occurred on its platform. The act of granting a video its virality or ephemerality belongs not to the mobile journalist, therefore, but to the company. Future studies must probe how social media platforms wield this power, and shape historic newsreels in the process.

Considering protester privacy

Social scientists can study the potential impact of digital archiving on protestors too.11Documenting the Now is a group that endeavors to provide ethical social media archivist tools to activists and grassroots organizations. Read their white paper on ethical community archivism, Bergis Jules, Ed Summers, and Vernon Mitchell, Jr., “Ethical Considerations for Archiving Social Media Content Generated by Contemporary Social Movements: Challenges, Opportunities, and Recommendations” (white paper, Documenting the Now, April 2018). From June 2’s #BlackOutTuesday campaign, and until the July 4 Independence Day holiday here in the United States, my students and I mined more than 2 million videos that were tagged #JusticeforGeorgeFloyd from various social media platforms. My team and I found hundreds of dedicated citizen journalists who posted ephemeral videos, most commonly to Instagram Stories and Snapchat. Did these citizens have a “right to be forgotten,” even though they may have the only footage from a major protest in their town?12Jasmine E. McNealy, “The Emerging Conflict between Newsworthiness and the Right to be Forgotten,” Northern Kentucky Law Review 39, no. 2 (2012): 119–136. Moreover, if we were to curate our data and make it available to the public eventually, what potential harm could we bring to the citizen journalists who had hoped to disappear their civic participation? This was an especially tragic point of discussion among Ferguson protestors, who urged the public to remember the six high-profile Black men activists who died suspiciously after being photographed incessantly in 2014.13→EJ Dickson, “Mysterious Deaths Leave Ferguson Activists ‘on Pins and Needles’,” Rolling Stone, March 18, 2019.

→Madlin Mekelburg and Samatha Putterman, “Revisiting Concerns over Deaths of 6 Ferguson Activists,” Austin American-Statesman, June 5, 2020.

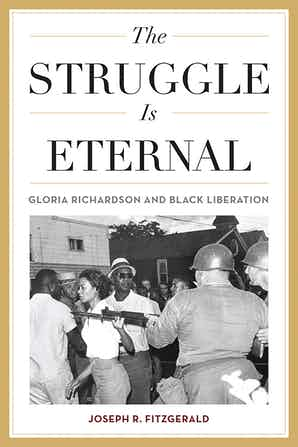

In response to these pleas, I observed a series of mobile applications that cropped up in an effort to obscure protestor identities. One of Stanford University’s new artificial intelligence tools placed brown fists over every face in a photograph, for example. Likewise, developers created tools that scrubbed EXIF metadata from pictures, and selectively blurred faces and other identifiable features.14Stanford University built a privacy bot to obscure protestor faces in crowd shots. Similarly, Everest Pipkin’s Image Scrubber is an open-source tool for anonymizing photographs taken at protests. What kinds of cultural and technological shifts have made these kinds of applications necessary? Social scientists need a sweeping literature review that discusses how facial recognition, deep fakes, policing via social media, and algorithmic bias have created the conditions for protestors’ guardedness and mobile journalism’s precarity. Moreover, media scholars should interrogate whether or not all of these applications that obscure one’s identity actually dilute the “affective” qualities—or the “mediated feelings of connectedness”—that protest journalism tends to bring forth.15Zizi Papacharissi, “Affective Publics and Structures of Storytelling: Sentiment, Events and Mediality,” Information, Communication & Society 19, no. 3 (2016): 307. Some of the most stirring iconography from the civil rights movement, for example, featured Black activists’ faces amid powerful displays of civil disobedience. Would the 1963 photograph of Gloria Richardson pushing away a US National Guardsman’s bayonet carry the same resonance had her face been blurred?16 Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2018More Info → We need a study that surveys how people remember (and react to) protest-themed photojournalism when faces are obstructed, to determine whether calls for protester privacy can live in a space that endeavors to save impactful protest journalism.

Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2018More Info → We need a study that surveys how people remember (and react to) protest-themed photojournalism when faces are obstructed, to determine whether calls for protester privacy can live in a space that endeavors to save impactful protest journalism.

Considering platform affordances

“Social scientists might investigate the front-end affordances that each platform provides for capturing protest journalism.”Finally, we can explore how a social media platform itself is conducive (or not) to producing protest journalism in the first place. My summer research team monitored Black Lives Matter protest coverage across Facebook Live, Instagram, Periscope, Snapchat, and TikTok. By the end of our observation period, we noticed that certain types of users seemed to favor discrete platforms over others. Instagram, for example, allows long-form video uploads with its IGTV feature. Its clunky mobile-first design, however—with its one-column, auto-play feature—is not easy to search. Thus, one of our research questions became, is this interface why serious mobile journalists—who livestreamed protests between four and six hours per day—seemed to avoid IGTV? They flocked instead to Periscope. Did these dedicated users find that their uploads were easier to share and archive there? Was it because Periscope content could be browsed on desktop devices, while IGTV cannot? Along these lines of inquiry, social scientists might investigate the front-end affordances that each platform provides for capturing protest journalism.17→Taina Bucher and Anne Helmond, “The Affordances of Social Media Platforms,” in The SAGE Handbook of Social Media, eds. Jean Burgess, Alice Marwick, and Thomas Poell (Sage Publications, 2018), 233–253.

→Elena Karahanna et al., “The Needs–Affordances–Features Perspective for the Use of Social Media,” MIS Quarterly 42, no. 3 (2018): 737–756. Doing so might help us narrow our search for high-quality protest journalism that is suited for digital archive research projects.

Social scientists would do well to consider the backend too. How easy is it for developers to shadow ban images of dissent, for example, thereby compounding the effects of ephemerality? I mention this because Instagram and TikTok admitted this summer that they did silence Black voices algorithmically, by hiding African Americans’ profiles and hashtags from in-app search.18→Starr Bowenbank, “Instagram CEO Adam Mosseri Pledges to Amplify Black Voices after Shadow Banning Accusations,” Cosmopolitan, June 16, 2020.

→Michelle Santiago Cortes, “Black Creators React to TikTok’s Apology and Share Experience of Suspected Shadowbanning,” Refinery29, June 5, 2020. A longitudinal study of this phenomenon would give us an idea of how a platform’s architecture can hasten ephemerality. If we find, for example, that livestreams of peaceful protests are removed or suppressed, while more violent imagery of cities on fire is allowed to remain in discoverable feeds, then we can begin to theorize about whether the social media platform mirrors legacy media’s normative news values about mediating protests. This kind of research would build upon current efforts to create a typology of protest coverage on social media around the world.19Summer Harlow et al., “Is the Whole World Watching? Building a Typology of Protest Coverage on Social Media from around the World,” Journalism Studies 21, no. 11 (2020): 1–19. It would also advance our understanding of the “protest paradigm,” which typically demonizes protestors and minimizes their demands.20Michael P. Boyle, Douglas M. McLeod, and Cory L. Armstrong, “Adherence to the Protest Paradigm: The Influence of Protest Goals and Tactics on News Coverage in US and International Newspapers,” International Journal of Press/Politics 17, no. 2 (2012): 127–144.

Breath, eyes, memory21I borrowed this section’s title from one of my favorite books of the same name. Edwidge Danticat’s Breath, Eyes, Memory remains, to me, one of the most searing explorations of identity and family heritage that I have ever read. I thought about each element of the title during the global Black Lives Matter uprisings this summer. Though Mr. Floyd was denied breath, Darnella Frazier served as the nation’s eyes and memory when she filmed his fatal police encounter.

Rep. John Lewis was the architect of a different kind of protest paradigm, which successfully brought the Southern horrors of the United States to mainstream audiences across the nation. It seemed full circle that his last public appearance was his visit to the stretch of 16th Street NW in Washington, DC, where the mayor had authorized city workers to paint the words, “Black Lives Matter” in bright yellow paint.22Jada Yuan, “Documenting John Lewis’s Last Public Appearance, Washington Post, July 30, 2020. He stood, masked amid the Covid-19 pandemic, on the road that led to the White House. At age 80, Lewis was using photojournalism to capture protest still.

In my own lifetime, I have spent a decade of teaching and researching the phenomenon of mobile journalism in the African American community. I am shifting now to focus on how I can help ensure that their digital protest journalism informs the newsreels of tomorrow. As social scientists, I believe it is our responsibility to continually probe the relationship between mobile devices, journalism, activism, and collective memory. We can do this if we bear in mind (1) the future historiographic impacts of ephemeral video’s precarity; (2) the dilemma of whether we should preserve a protester’s privacy or a photograph’s poignancy; and (3) the numerous platform affordances that often contribute to fleeting video and suppressed voices. These three broad areas of potential ephemeral video research will help us evaluate how power continues to shape mobile journalism practice, and history writ large.

We are at an odd crossroads, where we have more cameras than ever before—and even more vantage points—but limited places to archive that content for broad consumption. We can only study what we save. And we only tend to save that which we deem worthy of future analysis and cultural care. To hold onto mobile-mediated protest journalism, therefore, is to embrace the voices of the marginalized, ensuring that time does not erase their contribution to today’s news production.

Banner photo: Jacky Zeng/Unsplash.

References:

→Madlin Mekelburg and Samatha Putterman, “Revisiting Concerns over Deaths of 6 Ferguson Activists,” Austin American-Statesman, June 5, 2020.

→Elena Karahanna et al., “The Needs–Affordances–Features Perspective for the Use of Social Media,” MIS Quarterly 42, no. 3 (2018): 737–756.

→Michelle Santiago Cortes, “Black Creators React to TikTok’s Apology and Share Experience of Suspected Shadowbanning,” Refinery29, June 5, 2020.