The United States remains in a period of mass incarceration. The rate of incarceration—700 per 100,000 persons—is the highest among developed countries. Federal and state prisons confine 1.5 million people. Another 600,000 people are detained in local jails. These individuals are housed within 1,800 prisons and 2,800 local jails in the United States, which also employ over 400,000 correctional officers.

“Jails and prisons are hotbeds for the spread of communicable diseases like Covid-19.”Jails and prisons are hotbeds for the spread of communicable diseases like Covid-19. Anyone who has spent time in a correctional facility—voluntarily or otherwise—knows that close quarters, overcrowding, and inadequate healthcare render these institutions highly vulnerable to contagion. Social scientists and medical professionals were sounding the public health alarm throughout the early months of the disease’s arrival to the United States.1Stuart A. Kinner et al., “Prisons and Custodial Settings Are Part of a Comprehensive Response to Covid-19,” The Lancet Public Health 5, no. 4 (2020): E188–E189.

And yet, the New York Times reports that correctional facilities constitute seven of the top 10 leading hot spots for cases connected to Covid-19. At the top of the list, the Marion Correctional Institute, a prison in Ohio, has reported nearly 2,000 cases, amounting to over 80 percent of the facility’s population. Over 150 prison staff at this facility have also contracted the disease.

Official reports of infection counts, along with journalistic reporting, have come to represent the leading accounts of Covid-19 in one of our nation’s most vulnerable settings. Both sources are valuable but may not systematically capture what is being experienced in these institutions.

Social science research in prison during a pandemic

What can social science contribute to better understand and respond to Covid-19 in correctional facilities?

Social scientists are accustomed to gathering data under challenging circumstances. Research conducted in war zones and active drug markets or with political extremists or intravenous drug users is illustrative of the contexts and populations studied by social scientists.

Jail and prison populations are also notoriously difficult to study. Justice officials exercise an abundance of caution when allowing researchers into their facilities. Ethics boards apply stringent standards to research with incarcerated populations. The prisoners themselves can be reluctant to participate in research. This makes sense because there is a contentious history of research, especially medical research, in jails and prisons.2 New York: Routledge, 2013More Info →

New York: Routledge, 2013More Info →

The stakes are raised for collecting data in prisons during a pandemic. In the rush to thwart its outbreak, officials shut off access to correctional facilities. All 51 prison systems in the country suspended visitation and nonessential employees. Those decisions also apply to social science researchers. Studies occurring in jails and prisons across the country hang in the balance.

Our own study in Oregon, an evaluation of a solitary confinement step-down program, was in jeopardy. On-site interviews were slated to begin at the beginning of April with the first cohort of prisoners in the program, but that was no longer possible, because our universities restricted travel and the prison system restricted access.

We nonetheless ended up spending the month of April interviewing prisoners. The fast actions of our team, our universities, and the prison system made these interviews possible. We secured permission from our ethics board and prison authorities to alter our study protocols, shifting our mode of data collection from face-to-face to phone-based interviews. Our research team was dispersed across three states while the people we interviewed spoke with us by phone in an attorney room. Very few people declined to interview, which was at least somewhat surprising given the circumstances. We spent about 60 hours on the phone with a random sample of 31 high-security prisoners.

Views on Covid-19 from prisoners

What did we learn from prisoners about Covid-19?

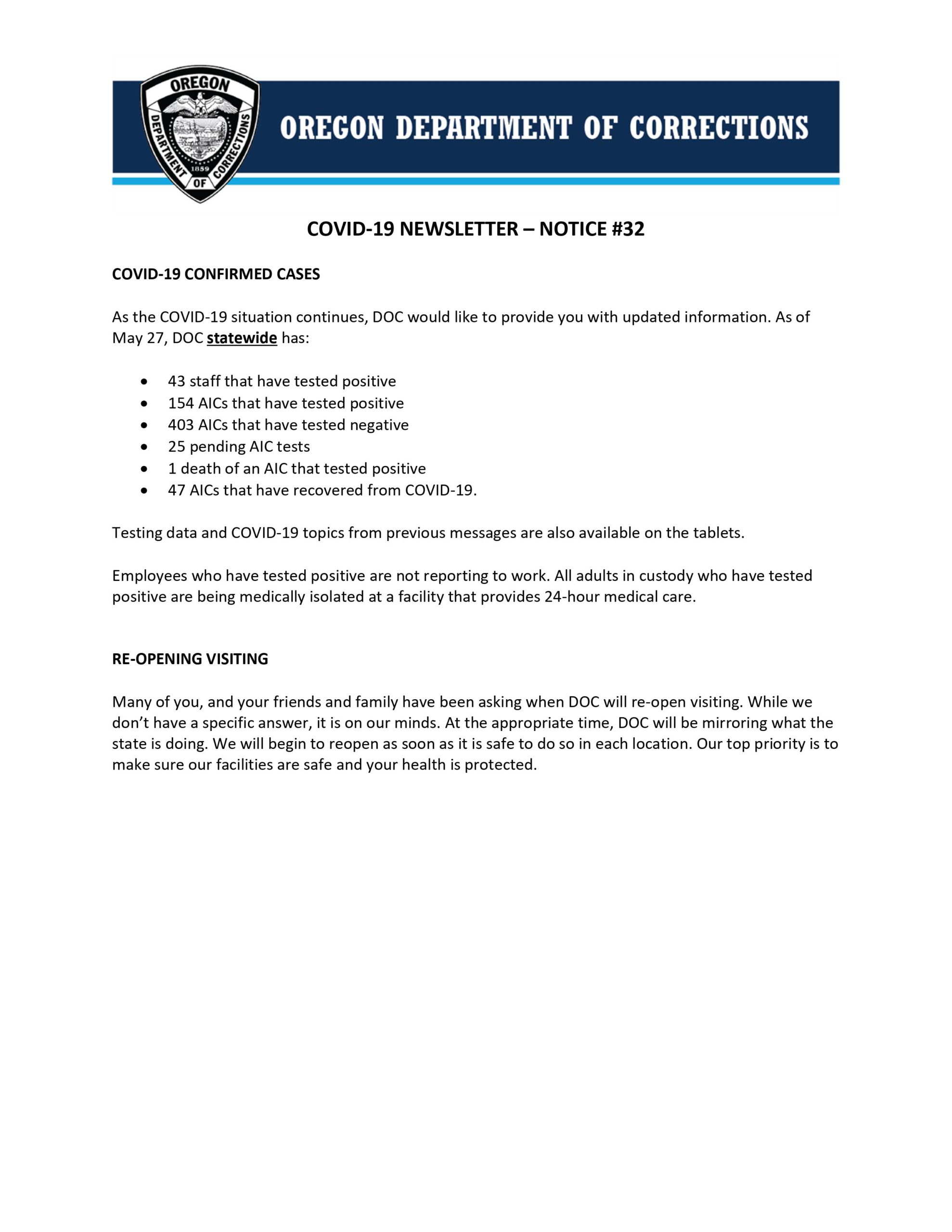

As of this writing, Oregon has been fortunate—only 157 of the 14,500 prisoners and 43 of the 4,400 corrections officers have tested positive for Covid-19. These estimates rank Oregon toward the bottom of prison systems impacted by the virus, according to researchers aggregating data at Covid Prison Data.

Prisoners in Oregon believed that the prison system was taking the threat of the virus seriously. Informational flyers communicated how the prison system was responding to the disease and included best practices to prevent its spread. Prisoners reported the presence of additional cleaning supplies, such as cleaners and disinfectants, in common areas. Recently, face masks were also distributed to prisoners.

Still, the threat of Covid-19 looms large. Prisoners felt that it is not a matter of if, but when, the virus would ultimately reach them and their facility.

Whereas people who shelter-in-place in their communities maintain a great deal of control over their surroundings, that is simply not the case in total institutions like prisons. Prisoners have no option other than to place their lives in the hands of the prison system. And these individuals maintained little confidence in the ability of the prison system to contain the disease. Many pointed to the correctional officers as the likely transmitters, owing to poor screening, asymptomatic transmission, and their time spent in the outside world.

The people we interviewed felt that they would not receive adequate medical treatment if they were to become infected. Many based their view on past medical experiences in prison. As one person put it, “You could break your toe, and [the doctor’s] going to tell you to gargle saltwater.”

“We were told by one respondent that ‘this is the one time in my life I’ve been grateful to be in isolation.’”Despite the distrust in the prison system’s preventative measures, our research shows physical distancing alleviates concern about Covid-19. Our interviews were with people in restrictive housing. While there are ethical and legal concerns with this type of housing,3Marie Garcia et al., eds., Restrictive Housing in the U.S.: Issues, Challenges, and Future Directions (Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice, 2016). the individuals we spoke with viewed their housing arrangement as beneficial for remaining virus-free. We were told by one respondent that “this is the one time in my life I’ve been grateful to be in isolation.” Many believed that their fellow prisoners who are double-celled or live in dormitory-style housing are at greater risk of infection.

Even a few additional hours spent with others appeared to increase concern about Covid-19. About half the people we interviewed were in near-complete isolation, spending around 23 hours a day alone in their cell. The other half were in a less restrictive condition, getting about three additional hours out of their cell. Those few hours—typically spent with other people—resulted in feeling less protected from contracting the virus.

Still, prisons are meant to do more than warehouse those who violate the social contract—they are also intended to rehabilitate.4 Elsevier, 2013More Info → The vast majority of prisoners will rejoin society, typically after just a few years of incarceration. Recidivism numbers remain stubbornly high in the United States, with around 80 percent of former prisoners rearrested within five years of release. Yet Covid-19 is disrupting efforts to improve the livelihoods of prisoners.

Elsevier, 2013More Info → The vast majority of prisoners will rejoin society, typically after just a few years of incarceration. Recidivism numbers remain stubbornly high in the United States, with around 80 percent of former prisoners rearrested within five years of release. Yet Covid-19 is disrupting efforts to improve the livelihoods of prisoners.

The loss of nonessential employees means that counseling and education services have ceased. The suspension of visitation is also problematic, because visits from family and friends can help prisoners cope with the stresses of imprisonment. Rehabilitative programs and visitations lower the risk of problem behavior, including recidivism.5→Mark W. Lipsey and Francis T. Cullen, “The Effectiveness of Correctional Rehabilitation: A Review of Systematic Reviews,” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 3 (December 2007): 297–320.

→Meghan M. Mitchell, Kallee Spooner, Di Jia, and Yan Zhang, “The Effect of Prison Visitation on Reentry Success: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Criminal Justice 47 (December 2016): 74–83. Alternative mechanisms are needed to deliver these services during a pandemic.

While the nation has remained on lockdown, it is nearly impossible to fully isolate the 2.2 million people in our nation’s jails and prisons. Many have called for early release as a solution, focusing on nonviolent prisoners or those nearing parole eligibility. While some jails have taken up the call, prison systems have been slower to respond despite executive orders from governors and judicial officials. Prisons house more serious offenders serving longer sentences than do jails. The potential consequences of releasing prisoners prematurely must be balanced against the health and welfare of those who live or work in these facilities.

A little effort can go a long way to prevent jails and prisons from becoming the epicenters of the Covid-19 crisis. Mitigating its spread will require screening and testing of staff and prisoners, providing masks and other protective gear, regular sanitization of living spaces, safe preparation of food, minimizing interpersonal contact, and better and increased communication with prisoners about the virus and the prison’s response.

The latter point bears further elaboration, as prisoners are at the mercy of authorities for information. Prisons are total institutions: Authorities and staff control where people live, with whom they associate, what they eat and read, and their health and safety. Anxiety runs deep among prisoners. Quelling that anxiety by sharing information is critical to the orderly function of institutions. Whereas some of the people we interviewed felt that the Oregon DOC was doing a good job by producing bulletins, others felt that this did not go far enough because the information provided was general to the prison system and not tailored to the specific prison in which they resided.

The continued need for social science

It is important to understand the views of prisoners when considering responses to challenges like Covid-19. Even though prisons are by their nature coercive institutions, they are typically a beehive of activity. Prisons are self-contained cities where prisoners live, work, learn, eat, sleep, socialize, and exercise. Any response requires their cooperation, or it runs the risk of civil disobedience, uprisings, or worse, collective violence. The Covid-19-triggered riots in Kansas and Washington state prisons illustrate these risks.

“Efforts to prevent the spread of Covid-19 throughout these facilities will pay dividends toward reducing the greater spread of Covid-19.”Jails and prisons are a vector for managing and responding to a public health crisis. They may feel like an entire world away from our communities, but they are far more closely connected than people might believe, due to the movement of employees and regular churning of prisoners. Efforts to prevent the spread of Covid-19 throughout these facilities will pay dividends toward reducing the greater spread of Covid-19.

This disease may ultimately restructure the functions and purposes of US prisons, not unlike its expansive impact on education, work, and social life in the United States. During the build-up to mass incarceration in the 1980s, sociologist Loïc Wacquant famously noted that researchers “deserted the scene” when they were needed the most.6“The Curious Eclipse of Prison Ethnography in the Age of Mass Incarceration,” in “’In and out of the Belly of the Beast’: Dissecting the Prison,” special issue, Ethnography 3, no. 4 (December 2002): 371–397. That was a mistake. Social scientists must be at the forefront of generating knowledge to understand and respond to Covid-19 while incarcerated populations remain at near all-time highs.

References:

→Meghan M. Mitchell, Kallee Spooner, Di Jia, and Yan Zhang, “The Effect of Prison Visitation on Reentry Success: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Criminal Justice 47 (December 2016): 74–83.