Hate speech is often seen as a binary choice. This is in part due to attempts to automate its detection or censor/sanction it, thus needing clear demarcations to classify when a piece of communication is or is not hate speech. A review of definitions in the literature, however, identifies multiple interpretations of hate speech, with some potentially more harmful for its targets than others. This article first distinguishes three major typologies of hate speech and then six categories that fit within them. These categories are then placed within a 6-point hate-speech intensity scale that is differentiated by their escalating advocacy of deadly violence.

A hate-speech intensity scale can offer an early warning that can be useful to a range of actors, including those producing the speech (for self-correction), platform companies, regulators, jurists, human rights advocates, journalists, and the targeted groups. If operationalized through a hate-speech monitoring system, such a scale can also be a proxy for potential real-world harm against different groups and societal polarization in general. Of course, any effort at hate-speech monitoring must be conducted with great care to avoid violating the free speech rights of individuals and prevent abuse by those who may use it for nefarious ends, such as limiting legitimate political dissent against those in power.

Defining hate speech

“The focus on the human emotion of hate and the general ambiguity regarding the term, however, has led a number of thinkers to question its usefulness and propose more specific terminology, such as dangerous, fear, and ignorant speech.”To begin any definition of hate speech, it is important to separately examine its two key words—hate and speech. Hate is a human emotion that is triggered or increased through exposure to particular types of information. Hate involves an enduring dislike, loss of empathy and even a desire for harm against particular targets.1Michael S. Waltman and Ashely A. Mattheis, “Understanding Hate Speech,” in Oxford Encyclopedia of Communication (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017). Hate speech is widely understood to target groups, or collections of individuals, that hold common immutable qualities such as a particular nationality, religion, ethnicity, gender, age bracket, or sexual orientation. Meanwhile, speech refers to communication over a number of mediums, including spoken words or utterances, text, images, videos, and even gestures. Hate speech, of course, is usually defined more broadly and includes insults, discrimination, dehumanization, demonization, and incitement to violence. The focus on the human emotion of hate and the general ambiguity regarding the term, however, has led a number of thinkers to question its usefulness and propose more specific terminology, such as dangerous, fear,2Antoine Buyse, “Words of Violence: ‘Fear Speech,’ or How Violent Conflict Escalation Relates to the Freedom of Expression,” Human Rights Quarterly 36, no. 4 (2014): 779–97. and ignorant speech.3Maxime Lepoutre, “Can ‘More Speech’ Counter Ignorant Speech?” Journal of Ethics and Social Philosophy 16, no. 3 (2019): 155–191.

When considering hate speech, it is important to point out that decades of research on persuasion and media effects have largely debunked claims of mass effects. In other words, while the public and political pundits often assume the masses can be easily swayed by the media, and especially through the use of propaganda, researchers have found that most people do not easily change their opinions, especially on issues where core values and beliefs are already set. As such, exposure to hate speech will likely have different effects on different individuals. On significant matters, such as hating others, individuals will often be predisposed to particular views built up over many years and react in ways that confirm their biases either in support or against a message. Furthermore, even when hate reinforces and radicalizes existing views or influences vulnerable audiences who may become more hateful due to exposure, other moral, cultural, and legal inhibitions often prevent people from turning such views into violent and criminal action.

Three major categories of hate speech

Hate speech often emerges from an “us vs. them” conceptual framework, in which individuals differentiate the group they believe they belong to, or the “in-group,” from the “out-group.” Hate speech toward the out-groups is segmented into three major categories in this analysis. The first, which is most often associated with hate speech, involves dehumanizing and demonizing the out-group and its members. The second moves from the conceptual to the physical and involves incitement to violence and even death against the out-group. However, before these two more intense categories, out-groups are often subjected to different types of negative speech, which is referred to as an early warning category here.

1. Dehumanization and demonization

Dehumanization involves belittling groups and equating them to culturally despised subhuman entities, such as pigs, rats, monkeys, or even germs or dirt/filth. A widely known recent manifestation of this phenomena involved calling the Tutsi minority in Rwanda cockroaches in the lead up and during the 1994 genocide. Dehumanization can achieve at least two political outcomes if successfully conveyed. First, it can collectivize members of the out-group into a detested single entity, depriving them of their unique individuality and humanity. This then leads to “guilt by association” in which all members of the group can be collectively blamed and held responsible for the negative actions of any members. Second, by depicting certain groups as being less than human, the in-group is released from any guilt stemming from supporting or committing violence against them. After all, the violence is no longer against fellow humans like us, but rather subhuman creatures that are widely disliked and already expendable in our minds. As Sam Keen has pointed out, “We think others to death and then invent the battle-axe or the ballistic missiles with which to actually kill them.”4Sam Keen, Faces of the Enemy: Reflections on the Hostile Imagination (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1991), 10.

Demonization, on the other hand, involves portraying a group as superhuman, like a monster, robot, or even fatal diseases like cancer that are a mortal threat to the in-group. When presented this way, the destruction of the adversary is not only acceptable, but even desirable and beneficial for the in-group’s survival. Demonization and dehumanization are an extreme typology of negative group characterization and a well-established tool for justifying political violence; thus, they merit their own category beyond more standard negative characterizations.5Babak Bahador, “Rehumanizing Enemy Images: Media Framing from War to Peace,” in Forming a Culture of Peace: Reframing Narratives of Intergroup Relations, Equity and Justice, ed. K.V. Korostelina (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 195–211.

2. Violence and incitement

While dehumanization and demonization characterize groups of people in extremely negative ways, they do not outright call for violence against them. However, another notable typology of hate speech involves incitement to violence. Within many jurisdictions, inciting violence against a particular group is a crime. At the international level, Article 20 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (United Nations) specifically mentions incitement as illegal, stating, “[a]ny advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law.” Even in the United States, where free speech is almost completely protected by the First Amendment of the Constitution, it is considered a crime to incite “imminent lawless action” when such action is both imminent and likely.

3. Early warning

A third category of speech that often borders what constitutes hate speech can be called “early warning” for the purposes of this analysis. The starting point of group-based hate speech is rarely dehumanization or incitement but rather usually more subtle and measured. Recognizing these early signs, however, can be helpful for preventing escalation toward more intense language. To this end, a very early precursor to hate speech is simply creating an in-group (“us”) versus an out-group (“them”) dynamic, and distinguishing “them” as a separate group with different ideas and beliefs. This can then lead to criticisms of the out-group’s negative actions, often conflating the actions of a few members with the entire group. Finally, negative actions, which have a one-off focus, can morph into the negative characterization of the entire group. These will be milder than the more extreme forms of negative group characterizations, such as dehumanization and demonization, and can involve referring to groups by negative traits—stupid, lazy, or dishonest—or it could associate the group with nonviolent criminality, such as theft or fraud. Such references can help develop hatred for out-groups which can, over time, make it easier to employ the more extreme types of hate speech.

Hate-speech intensity scale

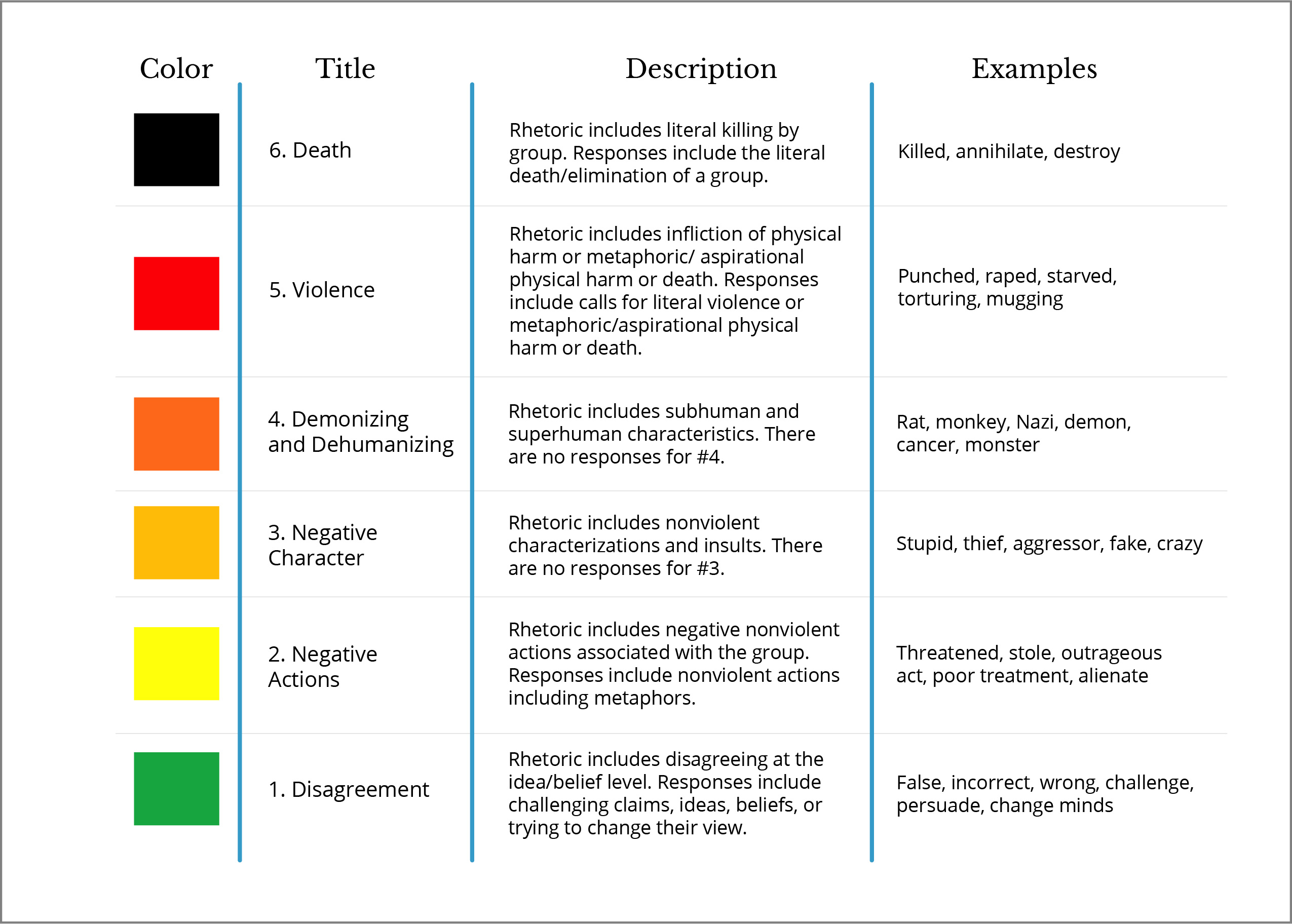

Within these three typologies, further categories are distinguishable that differ in their intensity. To make the scale easy to follow, a color, number, title, description, and examples for each category were placed into a Hate-Speech Intensity Scale and presented as a table (see Table 1). Within this scale, a distinction is made between rhetoric and response. Rhetoric includes negative words or phrases associated with the targeted out-group, which could refer to their past, present, or future actions or character. Response includes proposed actions that the in-group should take, either in response to the actions of the out-group or independent of the out-group’s actions.

The following section describes these six different categories. Categories 1 to 3 generally fall within the “early warning” typology; Category 4 includes the dehumanization/demonization typology; and Categories 5 and 6, which are the most intense, involve incitement to violence and death.

The first and earliest warning category is Disagreement, which involves disagreeing with the ideas or beliefs of a particular group. While there is nothing wrong with disagreeing with ideas or beliefs, what makes this category an early warning to future hate speech is the creation of the “us vs. them” framework. This is also problematic because in most cases, it will involve oversimplification and stereotyping of the out-group, as rarely will all members of the group think or believe in a uniform manner. Rhetoric will suggest, for example, that the out-group is wrong or hold incorrect beliefs while response will argue that we should take actions involving changing their minds or opposing them at the level of ideas.

“Responses involve nonviolent actions the in-group should do toward the out-groups, such as voting them out or protesting against them.”The second early-warning typology involves rhetoric that highlights nonviolent negative actions associated with the out-group, such as claims that the group stole or withdrew from a positive event. When such alleged actions are ambiguous on the use of violence (e.g., they stopped them) or use of nonviolent negative metaphors, they fit in this category (if unambiguous on violence, it’s classified a 5 or 6). Responses involve nonviolent actions the in-group should do toward the out-groups, such as voting them out or protesting against them.

The third early-warning typology includes negative characterizations or insults. This is worse than just negative nonviolent actions, as it makes an intrinsic claim about the group as opposed to a one-off action claim. As this category is not action oriented (unlike #1, 2, 5 and 6), there are no responses. The fourth category is also the second typology and can be considered an extreme form of negative characterization involving dehumanization and/or demonization. Like the third category, there are no responses in this category.

The fifth and sixth categories are part of the third and most intense typology, involving violent actions and death. The fifth category refers to literal violence allocated to out-groups either in their past, present, or future nonlethal violent actions. This also includes metaphorical or aspirational violence that is either nonlethal or lethal. Responses call for literal nonlethal violence to the out-group such as assaulting them. The sixth category involves rhetorically referring to out-groups as killers (past, present, and future). Responses call for the in-group to kill the out-group.

Identifying hate speech

“Understanding the dynamics of hate speech and its intensification and escalation, therefore, can serve as a signal for the political changes that drive it.”To combat hate speech and its negative consequences, it is necessary to identify and monitor early signs of its development before more extreme forms manifest. Hate speech does not operate in a vacuum and its increase reflects a changing underlying political context that allows it to grow. This can involve growing disunity and polarization within states or rising authoritarianism that seeks to consolidate power domestically. It can also reflect mounting international tensions and signal shifts toward conflict and war between states. Understanding the dynamics of hate speech and its intensification and escalation, therefore, can serve as a signal for the political changes that drive it.

A hate-speech intensity scale allows us to move beyond the binary approach that dominates current hate speech research. It can also potentially be operationalized to help various actors with interests and stakes in the negative consequences of hate speech to better identify and understand its evolution before it leads to real-world harms.