Following the publication of his debut book of poems, Heed the Hollow, Malcolm Tariq discussed with the SSRC the varied and interconnected themes found in his poetry, as well as his academic work. He explains how he combines his academic and creative pursuits in his craft, delving into the role interdisciplinarity plays in better understanding and illustrating the trauma of Black history and the Black experience, particularly in the American South. Yet, he also touches on the exploration of sexuality and queerness through his work. Reflecting on his learning experience, in classrooms, the archive, and life, Tariq enlightens us to the truths represented in stanzas and the stage, beyond simply data.

Malcolm Tariq is from Savannah, Georgia. He is a graduate of Emory University, and holds a PhD in English from the University of Michigan. In 2016, Tariq was a fellow of the SSRC’s Dissertation Proposal Development Program. He is the author of Heed the Hollow (Graywolf Press, 2019), winner of the 2018 Cave Canem Poetry Prize. Tariq completed a playwriting apprenticeship at Horizon Theatre Company in Atlanta, Georgia, and is a 2020–2021 playwright resident with the Liberation Theatre Company in Harlem, New York. He lives in Brooklyn, New York, where he is the programs and communications manager for the Cave Canem Foundation, a home for Black poetry.

How did you become interested in poetry and what led you to pursue your PhD in English?

Poetry came before the PhD. I was always a writer; I grew up writing short plays. A lot of people grow up singing in church, I started writing plays in church—plays that weren’t great. First, I tried to write fiction, then I started writing poetry and that just stuck. In high school, I learned about Cave Canem and when I was 19, I submitted a book for the Cave prize. It wasn’t great. It’s very silly when I think about it. In college I was going to major in creative writing, since I didn’t initially want to get a bachelor’s degree in English, because I thought that I read and wrote so much growing up and needed to try something new. However, I would go on to major English at Emory, spending 4–5 years studying literature and not doing much writing.

I always a very ambitious child, always making plans. I knew when I was applying to Emory that I wanted to get my PhD in something because I wanted to be a teacher, a professor. I was mostly always on that path. When I went to grad school at the University of Michigan, my first year I obtained a Cave Canem fellowship. I attended classes, and I had time to rededicate myself to writing while studying for my doctoral program at the same time. I was very intentional about cultivating a doctoral experience that wasn’t just focused on academic research and teaching, so I opened myself up to new opportunities. I had the opportunity to participate in its great MFA program. Because I was a writer, my critical training influenced my creative output a lot.

You mentioned that you were really intentional about crafting a doctoral program that wasn’t solely focused on the traditional path, i.e., landing a tenure-track job and publishing. What advice do you have for graduate students?

My advice is to always to treat the graduate experience as if it’s yours, because it is. Open yourself up to possibilities that aren’t the ones you think you should be doing and remember to cater to yourself and not your advisor or your program, because a PhD program is already stressful enough. It takes a lot of energy to do a PhD. I was 23 when I started my PhD. It was a great opportunity to learn about myself and to learn about the work I wanted to do. It also gave me the time to read and study, especially if you’re on fellowship, since you probably won’t get a chance to do that again, to just soak up information.

In your dissertation, “Versing the Ghetto: The African American Urban Narrative, 1940–1995,” you explore Black artistic production in cities during and after the Great Migration and how Black Americans portrayed and imagined themselves versus outside portrayals. In your poetry collection, Heed the Hollow, you examine queerness, slavery, and intergenerational trauma in the American South, using the motif of the “Black bottom.” What prompted you to shift from your dissertation’s themes to those of Heed the Hollow? What do you see as the commonalities and differences between these two projects?

I wrote the book at the same time I wrote the dissertation, the summer of 2016, when I became a Cave Canem fellow. When I was in graduate school I wrote one poem called “tabby,” which is the last poem of the book, based on me finding out what tabby is when I was visiting home one summer. Tabby is essentially a concrete-like material made of oyster shell, linestone, sand, ash, and water, which was largely produced by ensaved Black people. It was used to make buildings and structures along the southeastern coast, including the housing for the people that produced it. The poem challenges the dominant narrative of the Confederacy, but also invokes a myth-like telling of the brutal experience of enslaved Black people through the story of a mother and her stillborn child who are thrown overboard during the journey across the Atlantic. While their souls live on in the water and natural resources used to make tabby, they also haunt those who survived the journey and have to produce the tabby.

At the same time, I also started writing about queerness, sexuality, and identity and somehow the two—Southern history, slavery and trauma—and—the more like evocative sexual stuff—became the two ends of the book. I wrote toward a meeting point. At the same time, when this project started to solidify, I moved unto the dissertation. I like to have different projects, because that made my scholarship better, but it also made my poetry better. I would pregame writing a dissertation chapter by writing a poem to make me feel good, because poetry’s my feel-good place.

And for the dissertation, I’ve always been a community-focused person. I was writing to Black working class communities, instead of a field, so I would have to explain that to my committee sometimes. They’d always say, “This is what the field is saying,” and I’d reply, “Okay, but I want to create a document my mom could pick up and try to understand what’s happening.” Because I was writing my dissertation with that audience in mind, when I started writing the poetry book I was able to detach myself from the project. In graduate school, I was thinking about what would Southern studies be if it was centered on the Black queer experience, so to me the poetry book was also like the dissertation; it was that same process. I wrote both at the same time and I think that’s why the book reads the way it does, because the “I” is not always me in the book. It’s more open, it’s more collective, it’s not so personal.

Oftentimes people consider artistic production and academic production as separate, disparate things and that they’re in conflict. How and where do academia and poetry intersect for you?

At Michigan there are PhD programs that are English/creative writing, but even when you’re getting your MFA, you’re taking literature classes as well, so you’re getting that critical piece alongside the creative workshop. When I was in graduate school, people thought that my dissertation was on poetry. I’m also a playwright, so when I was at Atlanta in the theater, people assumed my PhD was on theater. When I corrected them, they were perplexed that I would investigate more than one thing. Academia allowed me to imagine what I was writing into. We studied disciplines and time periods, like the Harlem Rennaissance, so I was able to write into “how can I imagine the conversation now and what’s my contribution to that conversation?” For me it was more focused on “I’m not only writing a book, I’m part of a larger thing,” which is why the “I” is not me in the book sometimes. Some of it’s my lived experience, it’s not so specific where it’s just me. That’s what graduate school did for my creative outlet; it allowed me to ask, “Who am I writing with?” as opposed to writing a poem. There are other people here and what am I doing and what’s my contribution.

In New York City, there’s been a lot of popular art that looks at issues of slavery and trauma—I’m thinking of plays like Sugar in Our Wounds and Slave Play, which are pretty popular right now. How do you see your work in conversation with other works by Black creators that touch on themes of sexuality, queerness, intergenerational trauma, and slavery, both past and present?

When you’re writing about trauma and pain, especially generational trauma and especially Black people in the Americas, I think audience. The sensationalism around these topics have been there all the time and now we’re moving toward taking care of our audience members, especially if you’re writing about Black subjects for Black audiences.

I think that when I was writing, I asked to do an interview because I told you I’m usually being interviewed by poets, so the reference points would not have been plays, it probably would’ve been poetry, so I like that you made me think a lot about my process. When I was writing I thought about other poets who were writing similar things. There’s also a poem called “Slave Play” in the book so readers have asked me about the play sometimes. And now, when I do readings, before I read the poem, I explain that its not about the play and to not discuss it since I have yet to see it. I mean they are all existing together at the same time.

When I was sat down to do the book and I noticed what I was doing, in the days of Tumblr, I discovered the “Queering Slavery Working Group,” which focused on reading and writing histories of intimacy, sex, and sexuality during the time of slavery. I think there’s a Twitter archive of it. Jessica Marie Johnson and Vanessa Holden started it. I was thinking about the academic piece as well as some of the poetry piece, but I don’t think I had really thought about how I positioned myself in it yet, because there’s a lot of distance. But I do think it’s an exciting time to be writing stuff like this. People are writing from different vantage points. Works like Donja A. Love’s Sugar in Our Wounds and even some of my stuff are not so much based on fact, but on what was possible, allowing the audience to exlore these themes not just through a scholarly perspective, but also a creative one. It’s influencing people to go out and think about these issues and themes, and also it complicates how slavery exists in the American imaginary.

When thinking about slavery, Americans tend to think of the plantations and enslaved working the field, but I’m from Savannah, Georgia, and Savannah was a city. Slavery was not always in a field. It was in a house, with slaves sleeping in the house, there was no field and house separation. The story also is different by state, which is where the scholars come in. I’m writing a play now that deals with queerness, slavery, and time travel, and I’m reading a lot about slavery in Savannah. It’s so different from what I was taught, even living in Savannah as a child. I think what we’re doing, as creatives, is really providing that nuance for a public audience.

When you say that what you and other authors are writing is not only based in fact, but push ideas of what we can imagine, because there’s so much that isn’t in the archive and that can’t be in the archive when delving into issues of oppression and slavery. Recently, there has been a strong push toward “empirical,” quantitative research, and this valorization of data. What role do you think arts and autoethnographies can play in expanding and rounding out how we understand this era when data is king in our policymaking processes, especially surrounding issues of race, trauma, and slavery?

My issue with data is that while it tells a story, it’s not always the complete story. When you look at numbers, facts, and figures, they don’t always take into account lived experiences, empathy, and feeling. All these things should be a part of decision making. Depending on how it’s found, data is used to vilify certain communities and people, and to create laws and decisions that are not always best for everybody. They’re best for certain people. This is something that one of my advisors pushed me to think about when writing my dissertation, because I had four chapters, each based on a specific writer. I was writing about Black communities. I wanted my artists to be from the communities they were writing about. My advisor asked me, “Why is that the case and what can literature tell us that we can’t get from social sciences?”

There was a piece about social science in my introduction. I really had to think about it and it goes back to that stuff about data and numbers. When sociology was introduced as a field of study in the United States, it wasn’t that well thought out. Of course, a field is always developing, but the Chicago School of Sociology did a lot of experiments on Black people on the southside of Chicago that weren’t always as careful as they should have been. They were using Black communities as labs basically, which is not good. The literature by Black writers I included takes us to a more humane place and makes us think about the decisions we make; and it also provides us a more complete narrative. So even if, for example, Donja Love’s play isn’t based on actual facts, that isn’t to say that the situation did not happen. We can use what we know to be true to create narratives, but how can we as writers and artists bring an emotional element that creates connection and understanding that data does not offer.

Fiction allows us to escape our preconceived notions and to consider other possible scenarions/realities. There’s fact, but there are also other truths. That’s what I like about working with literature and about being a literary artist: we provide thought provoking-inquiries, and imagine what could happen. For example, Toni Morrison’s Beloved was based on an article she found in an newspaper, which led her to do further research. This approach is really powerful, because it frees the mind and allows us, as artists, to make these stories and themes tangible. It gets me to really think about the power of myth. Myth is something you can grow up with and it can be this fun thing that we don’t know if it’s true or not. But myth also has power, so we think about how we are going to use that to our advantage.

To circle back a little bit, you participated in the DPD Program, which focuses on interdisciplinarity and mixed-methods approaches. How did the program and its methodology shape your approach to your dissertation, and what role does interdisiplinarity play in your own artistic process?

When I was applying to Michigan, they really stressed interdisciplinarity. Their English Department had no period requirements, which freed me up to take a lot of classes outside of my department. I took a lot of history classes and women’s studies classes. I took a playwriting class. Taking these classes and the program’s interdisciplinary approach pushed me to think about having a more nuanced narrative, but to also participate in several conversations, or peer in on several conversations. I’m really inspired by looking outside of the field or the scope of what I’m working on or what I’m taught to look in.

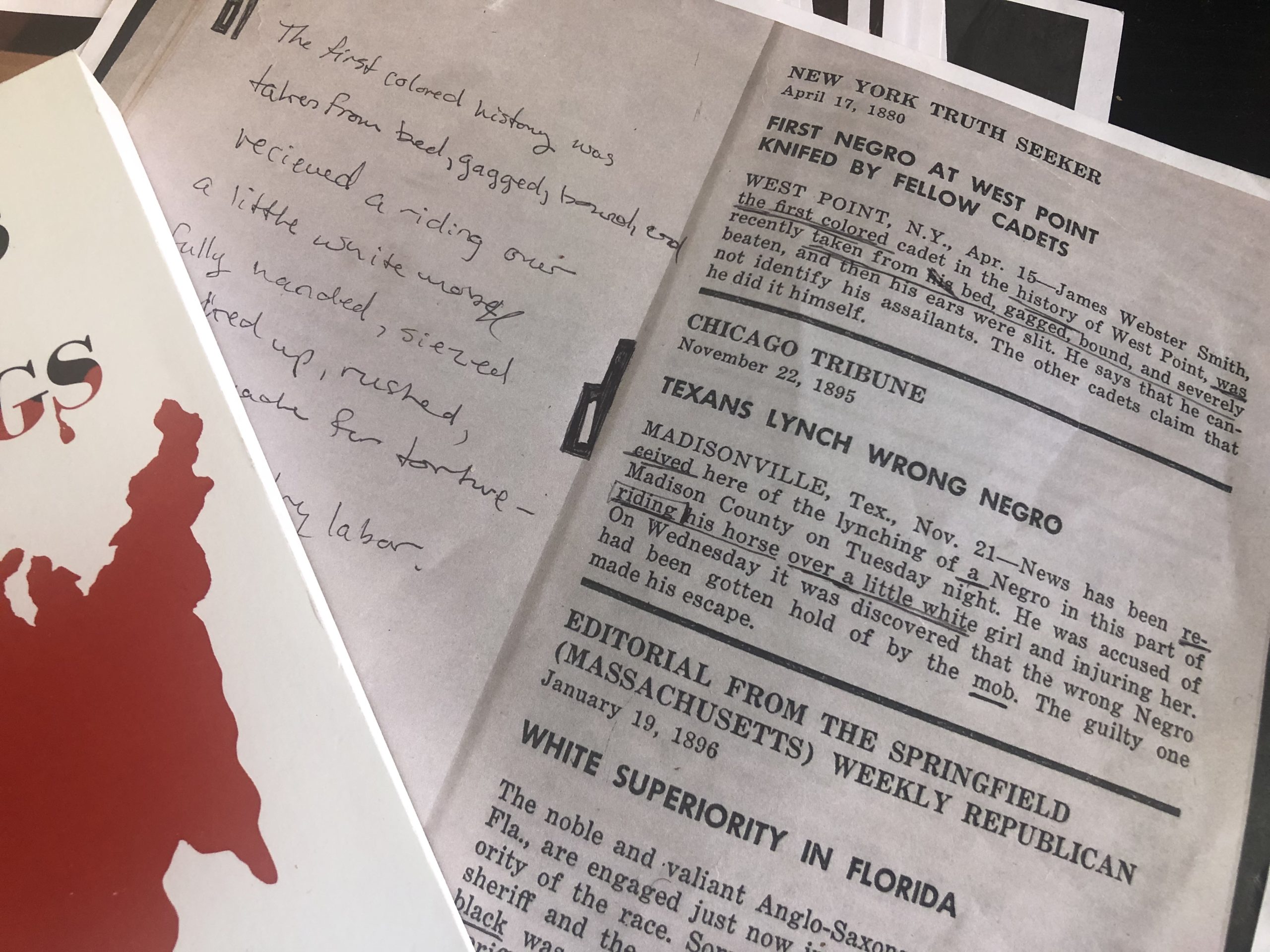

When I participated in the DPD summer workshop, I was at times frustrated because we were all coming from different disciplines. I remember there was a fellow in public health and I was, at first, unsure but after learning about her research, I was intrigued by her approach to public health, which applied a Black feminist, humanistic, humanities-based theory, to data use. Though getting feedback from so many people at one time was a lot, it helped me to think about the direction I was going in and all the things I had to consider. And so when I was on the road doing my research in the archive, I would also run into stuff that was related to my poetry project. It allowed me to question how, for example, a Ralph Ellison piece fit into a poem I wrote on so-and-so topic. It was great to bring that type of practice into the poetic experience. If somebody asked me what do I do when I have writer’s block or lack inspiration, I just sit in it; I don’t always have to be writing something. You can just look up a keyword in the archive and something will pop up, which is great.

What do you enjoy most about your work and your poetry?

One thing I like, as a Southerner, a Black Southerner, from a very specific place, Savannah, is getting to archive some piece of history in a creative way, so it exists in different communities and mediums. Especially, as cities and communities change, I allow what I grew up with to live on, in a way. That’s really important to me.

What advice would you give your 19-year-old self who wrote the book?

Going back to interdisciplinarity, I would say, “Read, read, and read. Read outside of what you know.” When I was younger I would go to the poetry section—it’s always small in the library—and pull a book out, and you’ll see a name. Then you’ll go other places and you’ll see it again, and you’ll say, “Oh I saw that Gwendolyn Brooks name somewhere, let me try to read that.” What also was really important to me was to imitate other people that I liked. First, imitation and then, creation. That’s how I developed my own voice, after imitating other people and spending all that time in college not writing, but studying, reading, and learning about the craft. After college and returning home, one of my friends read something I wrote and they said, “Oh yeah, this sounds like you,” and I asked, “What do I sound like?” Because I didn’t know, and then I read it and I was like “Oh yeah, this does sound like me.”

Banner photo courtesy of Malcolm Tariq.