After World War II, the United States was filled by an unprecedented optimism about the country’s prospects. As President Harry Truman put it: “As the year 1947 opens, America has never been so strong or so prosperous.”1“Economic Report of the President to the Congress, January 8, 1947” (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1947). Indeed, the war was finally over, the enemy had been defeated, and the United States was now the strongest economic, military, and political superpower in the Western hemisphere. Maintaining economic prosperity and superiority, however, would prove to be a difficult challenge. It was clear the government would have to assume this responsibility and take action through the creation of mechanisms that, like the Employment Act of 1946, would seek “all practicable means […] to promote maximum employment, production, and purchasing power.”2Employment Act of 1946, 15 U.S.C. § 1021 And, as the 1950s went by, there were some reasons to believe the government had advanced toward achieving these economic and social goals: the economy had experienced more than a decade of sustained growth with only minor recessions in between, the postwar depression many had feared would inevitably come had not materialized, and the insights of economists like John Maynard Keynes as well as the improvements in economic statistics had increased the effectiveness of the government’s response to recessions.

And yet, the memories of social disintegration and unrest, of mass unemployment, and of the economic frustration left by the Great Depression were still too vivid to believe that a full victory on social and economic problems had been achieved. The 1953–1954 and 1957–1958 recessions, in particular, were signs of a reduced but nonetheless persistent economic instability, and an important reminder for economists that there were still questions left to answer.

The SSRC’s Committee on Economic Stability

In June 1959 a group of 19 economists from academia, government agencies, and private institutions met for a three-day conference at the University of Michigan to discuss the persisting instability of the US economy. Organized by Robert A. Gordon (UC Berkeley), the conference aimed at understanding the type of “minor cycles” that the economy had experienced since the end of World War II. For Gordon, economists were still not able to explain these minor cycles, and some of the business-cycle theorists seemed content with developing mathematically elegant models that bore no resemblance to the actual postwar experience of the US economy.

The discussion at the conference led to a proposal for the creation of a Committee on Economic Stability at the Social Science Research Council (SSRC), which was successfully established by the end of the year. Besides Gordon, who acted as chairman during the first three years, the committee’s initial lineup consisted of Lawrence R. Klein (U. Pennsylvania), James Duesenberry (Harvard), Bert Hickman (Brookings Institution), Geoffrey Moore (National Bureau of Economic Research), and David Lusher (Council of Economic Advisers). Their main functions, as Gordon explained, would be to (1) facilitate research coordination; (2) help integrate current research methodologies (in particular econometrics but also “historical” methodologies associated to the work of the National Bureau of Economic Research); (3) facilitate the collection and publication of needed data, particularly from the federal government; and (4) serve as a channel of communication and a facilitating agency in the field of research on problems of economic instability.3“Research on Economic Stability,” Items 13, no. 4 (December 1959): 37.

Months after its creation, the committee’s first project started taking shape. With a grant from the National Science Foundation and led by Duesenberry and Klein, a group of more than 20 researchers worked from 1961 to 1963 to build the largest macroeconometric model of its time. A macroeconometric model, in Klein’s words, is “a system of mathematical equations with statistically determined coefficients (determined from actual observations of the working of the economy) that attempts to describe economic activity” of the country as a whole.4Lawrence R. Klein, “The Dartmouth Conference on an Econometric Model of the United States,” Items 15, no. 3 (September 1961): 34. Unlike most of the contemporary theoretical work, the committee’s macroeconometric model would allow researchers to study the actual US economy. And due to the project’s size, the resources it mobilized, and its innovative organizational characteristics, the committee’s project marked an important milestone in the development of macroeconometric models for quantitative policy analysis.

It was handed over to the Brookings Institution in 1963 for further development and maintenance—becoming known as the Brookings quarterly model—and it inspired the development of macroeconometric models for the Department of Commerce’s Office of Business Economics and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in the second half of the 1960s.

A “federation of research projects” and other committee innovations

The SSRC’s macroeconometric model was not the first model of this type. In the mid-1930s, the Dutch economist Jan Tinbergen had pioneered the development of macroeconometric models in his work for the League of Nations. In the United States, Klein had built progressively larger models since the mid-1940s, first at the Cowles Commission in Chicago and then at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. The committee’s macroeconometric model, however, was substantially larger than previous ones, boasting over 100 equations—compared to Klein’s 1950 mark III and the 1955 Klein-Goldberger models, which had 16 and 20 equations respectively. This size served a purpose, but it also posed important challenges.

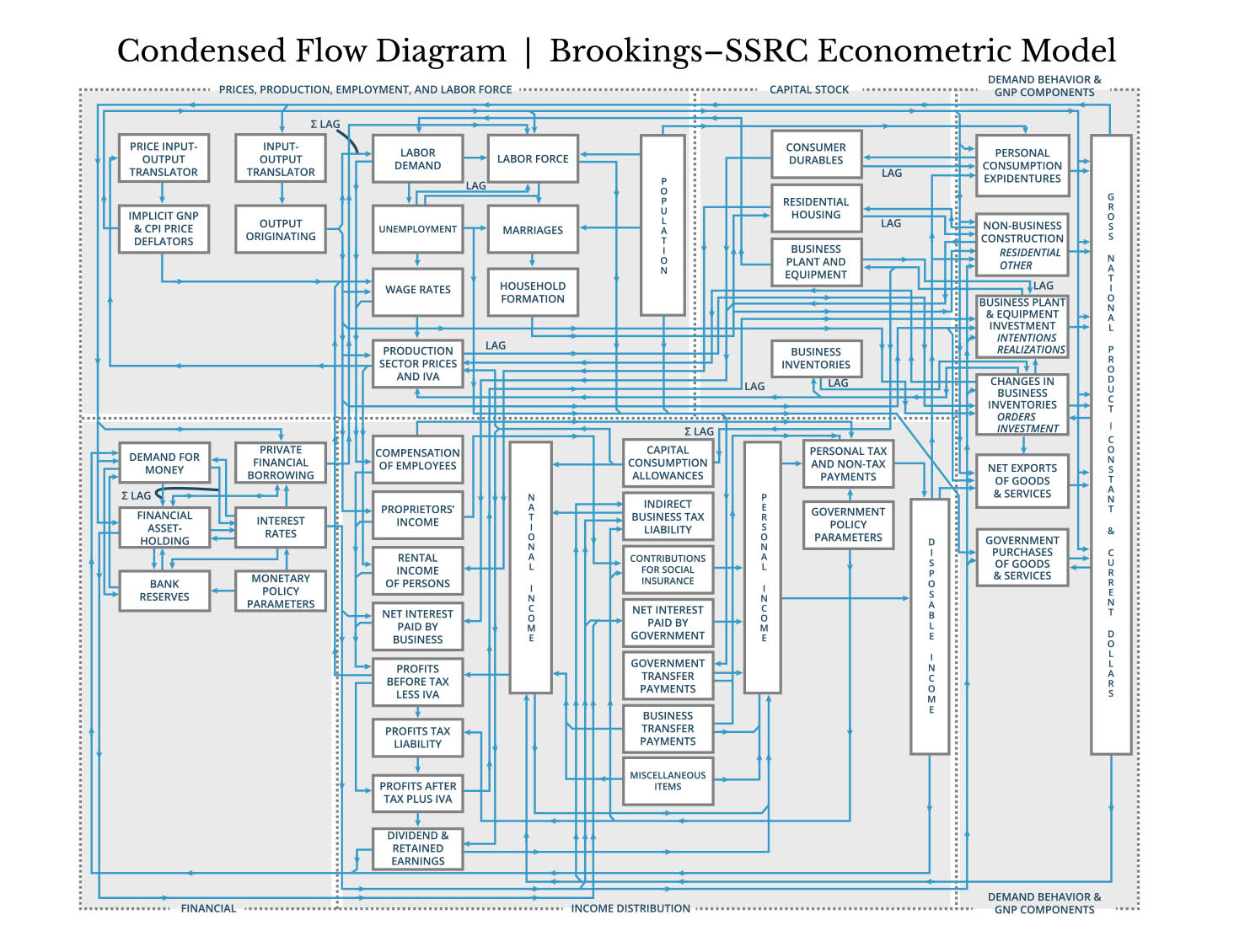

“Instead of dealing with highly aggregated variables such as a tax on aggregate output or the money supply, the committee’s model included variables that allowed model builders to measure the effects of changes in actual policy.”The main objective of building a larger model was to achieve a more detailed description of the economy (see Diagram 1). This was carried out by disaggregating sectors as much as possible and using variables that represented actual policy instruments (e.g., personal income tax, banks’ reserve requirements), which in turn would allow model builders to run computer simulations, or “experiments,” to evaluate specific government policies. Thus, instead of dealing with highly aggregated variables such as a tax on aggregate output or the money supply, the committee’s model included variables that allowed model builders to measure the effects of changes in actual policy. This concern for the model’s usefulness in the analysis of economic policies marked its planning and construction.

Diagram 15This is a “condensed flow diagram” of the model in its 1964 version, just after it had been handed over to the Brookings Institution. It shows the complexity of the model in terms of both the number of economic sectors included and the level of disaggregation. The diagram has been redrawn for better legibility but is otherwise identical to the original included in James S. Duesenberry et al., eds., The Brookings Quarterly Econometric Model of the United States (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1965).

At the same time, the structure of the project and the size of the model created some difficulties. First, the nature of the project made it impossible for it to be a “one-man job.”6We use the original term “one-man job” because this is the way in which economists such as Klein referred to previous and smaller projects. While it is true that most of the more “visible” team members were men, the literature on the history of computing has meticulously shown that women played a decisive role working as assistants and computer programmers. See, for example, Janet Abbate, “Recoding Gender: Women’s Changing Participation in Computing” (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2012). There’s every reason to believe that several women were also involved behind the scenes of the committee’s project as computer assistants and programmers at the various universities and institutions involved in the model. There is also evidence that several women worked as computer programmers during the development of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System’s model. See Juan Acosta and Beatrice Cherrier, “The Transformation of Economic Analysis at the Federal Reserve During the 1960s” (working paper, The Center for the History of Political Economy Working Paper No. 2019-04, Duke University, Durham, NC, 2019), 25. In fact, Tinbergen’s and Klein’s previous models had not been “one-man jobs” either. These models had also been built in small teams under the umbrella of a particular institutional framework, which provided the material conditions necessary for the creation of econometric laboratories. Yet, given the scope of the committee’s model and its level of disaggregation, the organizational challenges that this particular project demanded were even higher. Therefore, the project developed an important innovation by organizing as a “federation of research projects,” where teams of one to three researchers worked on individual sectors of the model and then met during weeks-long summer conferences at Dartmouth College to craft the collection of sector models into a sensible whole. Each of these individual sector models was built by specialists, and the project successfully gathered top talent from in and outside academia.7See Klein’s accounts of these summer conferences in “Dartmouth Conference on an Econometric Model,” 34 and “The Second Summer Conference on an Econometric Model of the United States: Summary Report,,” Items 16, no. 4 (December 1962): 37.

Second, the size of the model also posed important statistical and computational challenges. Franklin Fisher (MIT) devised a sequential estimation procedure that would allow the model to be estimated consistently, and Charles Holt and his team at the University of Wisconsin’s Social Systems Research Institute wrote Program SIMULATE to estimate and simulate the model.

And third, the number of variables included in the model made the availability of data and its management a major concern. The participation of government officials in the construction of some of the individual sectors and the development of a close relationship with the Department of Commerce greatly facilitated the task of getting the needed data series. Yet, a great deal of effort also went into creating physical and digital databases once the model was officially handed over to the Brookings Institution in September 1963, where it grew into the even larger and more disaggregated Brookings model.

The committee and the promotion of quantitative policy analysis

In August 1963, as the model project was coming to an end, the committee organized an international conference on quantitative policy analysis aimed at giving it more visibility among economists in the United States, including government officials. The organizers—Hickman, Holt, and Karl Fox and Erik Thorbecke (Iowa State)—explicitly wanted to make the case for the use of tools for quantitative policy analysis, such as the committee’s macroeconometric model in the United States, by showcasing the experiences of France, the Netherlands, and Japan. These countries had had a longer experience with various forms of quantitative policy analysis and, even if progress was still modest, they exemplified the advantages of such an approach. As a Brookings Institution research report on the conference and its proceedings put it:

The techniques of policy planning provide a rigorous and systematic method of exploring the impact on the economy of specific governmental actions. Their purpose is to supply the policymaker with a more scientific basis for choosing among alternative economic policies than is given by the rough estimates or intuition frequently underlying policy decisions.8“The Uses of Quantitative Economic Planning,” records of the SSRC. For a full reference, see Acosta and Pinzón-Fuchs, “Peddling Macroeconometric Modeling and Quantitative Policy Analysis: The Early Years of the SSRC’s Committee on Economic Stability, 1959–1963,” Œconomia – History / Methodology / Philosophy (forthcoming).

As the model project had done, the conference supported the idea that quantitative tools could be used for economic policy analysis, but the conference went a step further in arguing that these tools would lead to a better, more rigorous job.

“The rigorous and systematic methods for policy analysis advanced at the conference could help policymakers make better decisions but not determine the policy objectives.”At the same time, careful consideration was given to the role of these tools in the larger context of policymaking, explicitly recognizing that the quantitative policy analysis was subordinated to higher, and politically determined, objectives like price stability and full employment. Accordingly, in the introduction to the proceedings of the conference, Hickman reminded readers that quantitative policy analysis was “essentially a political problem.”9Bert Hickman, ed., introduction to Quantitative Planning of Economic Policy (Washington DC: The Brookings Institution, 1965), 1–17. The rigorous and systematic methods for policy analysis advanced at the conference could help policymakers make better decisions but not determine the policy objectives. These depended on the preferences of political parties, interest groups, and administrators and were scattered within a complex process that went down “to the art of finding legislation that stands a chance of passage in Congress” and that was dispersed among the political power of “various agencies, committees, and chairmen, as well as the Senate, the House, and the President.”10Charles C. Holt, “Validation and Application of Macroeconomic Models Using Computer Simulation,” in The Brookings Quarterly Econometric Model of the United States, eds., James Duesenberry et al. (Chicago: Rand-McNally, 1965), 637–650.

A lasting influence

The activities of the SSRC’s Committee on Economic Stability during the early 1960s laid the basis for the consolidation of large-scale macroeconometric modeling in the United States. For the first time, a large-scale model addressed key technical and logistical issues, and the committee’s experience was an important source of knowledge and guidance for future projects. In addition, the committee’s project also contributed to the broader use of digital computers in economics and to the development of computer programs to estimate and simulate this type of model. As evidenced by the goal of the 1963 conference on quantitative planning, these models did not play an important role in the policymaking process in the United States at the time, but the committee’s activities contributed to a long-term change.

The committee succeeded in bringing together academic and government officials, and macroeconometric models soon found a home in institutions like the Department of Commerce and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. These and other institutions, like the Congressional Budget Office, still use models that descend from the type of work done during the 1960s, and businesses all around the world buy services from private companies that sell access to forecasts and economic analysis based on large-scale macroeconometric models.

This essay draws from our ongoing research on the SSRC’s Committee on Economic Stability and in particular from our article “Peddling Macroeconometric Modeling and Quantitative Policy Analysis: The Early Years of the SSRC’s Committee on Economic Stability, 1959–1963,” Œconomia – History / Methodology / Philosophy (forthcoming).