Over the past generation, an economic transformation has taken place in the heart of the middle class family. The once-secure family that could count on hard work and fair play to keep it safe has been transformed by current economic risk and realities. Now a pink slip, a bad diagnosis, or a disappearing spouse can catapult a family from solidly middle class to newly poor in a few months.

The American family has been hit on every front. Rocked by rising prices for essentials and wages for men that have remained flat, middle class families have put both Mom and Dad into the workforce, a strategy that has left them working harder just to try to break even. Expenses for the basics have shot up, squeezing the family balance sheet so that even a small misstep can leave the family in crisis. The old financial rules have been rewritten by powerful corporate interests who see middle class families as the spoils of political influence.

Income

The changes in the basic economic structure of the American family are staggering. In just one generation, millions of mothers have gone to work, so that the typical middle class household in America is no longer a one-earner family, with one parent in the workforce and one at home full-time. Instead, the majority of families with small children now have both parents rising at dawn to commute to jobs so that they can both pull in paychecks.

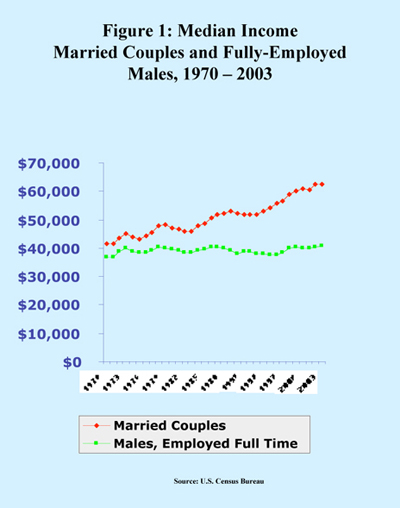

Many have debated the social implications of these changes, but few have looked at its economic impact. Today a fully employed male earns $41,670 per year. After adjusting for inflation, that is nearly $800 less than his counterpart of a generation ago. The only real increase in wages for a family has been the second paycheck added by a working mother. With both adults in the workforce full-time, the family’s combined income is $73,770—a whopping 75 percent higher than the household income for the family in the early 1970s. But increasing family income by sending more people into the workforce has an overlooked side effect: family risk has risen as well.

Today’s families have budgeted to the limits of their new two-paycheck status. As a result, they have lost the parachute they once had in times of financial setback—a back-up earner who could go into the workforce if the primary earner (usually Dad) got laid off or was sick. This phenomenon, known as the added-worker effect, could buttress the safety net offered by unemployment insurance or disability insurance to help families weather bad times. But today, with all workers already going—and spending—flat out, there is no one left in reserve to step in during the tough times. Any disruption to family fortunes can no longer be made up with extra income from an otherwise-stay-at-home partner.

Income risk has shifted in other ways as well. As Jacob Hacker and Nigar Nargis have shown, incomes today are less dependable, with the odds of a significant interruption double that of a generation ago. Moreover, the shift from one-income to two-income status has doubled the family’s risk of facing a period of unemployment. Of course, with two people in the workforce, the odds of income dropping to zero are less than for a one-income family. But for families where every penny of both paychecks is already fully committed to mortgage, health insurance, and other payments, then the loss of either paycheck can send them into a financial tailspin. With two workers, the odds that someone will be laid off so that the family can’t meet its bills have doubled in a single generation.

On the health front the family faces a host of new risks as well. Two jobs means either Mom or Dad could be out of work from illness or injury, losing a substantial chunk of the family income. The new everyone-in-the-workforce family faces another risk as well. When there was one stay-at-home parent, a child’s serious illness or Grandma’s fall down the stairs was certainly bad news, but the main economic ramifications were the medical bills. Now, with both parents in the workforce, someone has to take off work—or hire help—in order to provide family care. At a time when hospitals are sending people home quicker-and-sicker, more nursing care falls directly on the family—and someone has to be home to administer it.

Even the economic risks of divorce have changed. A generation ago, divorce was an economic blow, but a non-working spouse usually took a job, bringing in new income to stay afloat. When today’s two-income family divorces, there is no one to take on a new job and produce new income to cover the rent and buy the groceries. The only change for a divorcing couple is that what they earn now has to cover several new expenses. Evidence mounts that both post-divorce women and post-divorce men are struggling to make ends meet as they try to support two households on the same combined income. A divorced woman with children, for example, is about three times more likely to file for bankruptcy than a man or woman, single or married, without children. And men who owe child support are about three times more likely to file for bankruptcy than men who don’t.

For single parents, the news is even worse, as they face all the difficulties of dual-income families: All income is budgeted, there is no one at home who can work if the primary earner loses a job or gets sick, and no one is around to take over if a child gets sick or an elderly parent needs help. They face all the same risks, but the one-parent-one-earner family is trying to make it on a lot less money, competing for housing, daycare, health insurance, and all the other goods and services. As one divorced, working mother put it, “With what my ex contributes and what I earn, I can just about match what a man can make, but I can’t match what a man and woman both working can make.” The two-parent families are struggling to swallow the risk, but their single-parent counterparts are choking. Does this mean that middle-class women should return to the home in order to reduce their families’ risk? Before jumping on that bandwagon, it is important to look at the expenses facing middle class families.

Expenses

Why are so many moms in the workforce? For some it is the lure of a great job, but for millions more, it is the need for a paycheck, plain and simple. Incomes for men are flat at a time when expenses are rising sharply. Fully 80% of working mothers report that their main reason for working was to support their families. In short, families now put two people in the workforce to do what one could accomplish alone just a generation ago.

It would be convenient to blame the families and say that it is their lust for stuff that has gotten them into this mess. Indeed, there are those who do exactly that. Sociologist Robert Frank claims that America’s newfound “Luxury Fever” forces middle-class families “to finance their consumption increases largely by reduced savings and increased debt.” Others echo the theme. A book titled Affluenza sums it up: “The dogged pursuit for more” accounts for Americans’ “overload, debt, anxiety, and waste.” If Americans are out of money, it must be because they are over-consuming, buying junk they don’t really need.

Blaming the family supposes that we believe that families spend their money on things they don’t really need. Over-consumption is not about medical care or basic housing; it is, in the words of Juliet Schor, about “designer clothes, a microwave, restaurant meals, home and automobile air conditioning, and, of course, Michael Jordan’s ubiquitous athletic shoes, about which children and adults both display near-obsession.” And it isn’t about buying a few goodies with extra income; it is about going deep into debt to finance consumer purchases that sensible people could do without.

But is it true? Intuitions and anecdotes are no substitute for hard data. If families really are blowing their paychecks on designer clothes and restaurant meals, then the expenditure data should show that today’s families are spending more on these frivolous items than ever before. But the numbers don’t back up the claim.

A quick summary of the Consumer Expenditure Survey data paints a very different picture of family spending. Consider what a family of four spends on clothing. Designer toddler outfits and $200 sneakers are favorite media targets, but when it is all added up, including the Tommy Hilfiger sweatshirts and Ray-Ban sunglasses, the average family of four today spends 33 percent less on clothing than a similar family did in the early 1970s. Overseas manufacturing and discount shopping mean that today’s family is spending almost $1200 a year less than their parents spent to dress themselves.

Consider food, another big target as families eat out more and buy designer water and exotic fruit. Today’s family of four is actually spending 23 percent less on food (at-home and restaurant eating combined) than its counterpart of a generation ago.

Appliances tell the same picture. There is a lot of complaining about microwave ovens and espresso machines. Affluenza rails against appliances “that were deemed luxuries as recently as 1970, but are now found in well over half of U.S. homes, and thought of by a majority of Americans as necessities: dishwashers, clothes dryers, central heating and air conditioning, color and cable TV.” But manufacturing costs are down, and durability is up. Today’s families are spending 51 percent less on major appliances today than they were a generation ago.

This is not to say that middle-class families never fritter away money. A generation ago no one had cable, big-screen televisions were a novelty reserved for the very rich, and DVD and TiVo were meaningless strings of letters. So how much more do families spend on “home entertainment,” premium channels included? They spend 23 percent more—a whopping extra $180 annually. Computers add another $300 to the annual family budget. But even that increase looks a little different in the context of other spending. The extra money spent on cable, electronics, and computers is more than offset by families’ savings on major appliances and household furnishings alone.

The same balancing act holds true in other areas. The average family spends more on airline travel than it did a generation ago, but it spends less on dry cleaning. More on telephone services, but less on tobacco. More on pets, but less on carpets. And, when we add it all up, increases in one category are offset by decreases in another.

So where did their money go? It went to the basics. The real increases in family spending are for the items that make a family middle class and keep them safe (housing, health insurance), and that let them earn a living (transportation, child care and taxes).

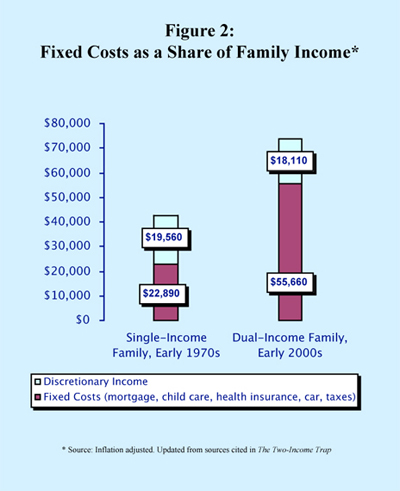

The data can be summarized in a financial snapshot of two families, a typical one-earner family from the early 1970s compared with a typical two-earner family from the early 2000s. With an income of $42,450 (all 1970s numbers are inflation adjusted), the average family from the early 1970s covered their basic mortgage expenses of $5,820, health insurance costs of $1,130 and car payments, maintenance, gas, and repairs of $5,640. Taxes claimed about 24 percent of their income, leaving them with $19,560 in discretionary income. That means they had about $1,500 a month to cover food, clothing, utilities, and anything else they might need—just about half of their income.

By 2004, the family budget looks very different. As noted earlier, while a man is making nearly $800 less than his counterpart a generation ago, his wife’s paycheck brings the family to a combined income that is $73,770—a 75% increase. But their expenses quickly reverse that bit of good financial news. Their annual mortgage payments are more than $10,500. If they have a child in elementary school who goes to daycare after school and in the summers, the family will spend $5,660. If their second child is a pre-schooler, the cost is even higher, $6,920 a year. With both people in the workforce, the family spends more than $8,000 a year on its two vehicles. Health insurance costs the family $1,970, and taxes now take 30 percent of the family’s money.

The bottom line: today’s median earning, median spending middle class family sends two people into the workforce, but at the end of the day they have about $1500 less for discretionary spending than their one-income counterparts of a generation ago.

What happens to the family that tries to get by on a single income in today’s economy? Their expenses would be a little lower because they can save on child care and taxes, and, if they are lucky enough to live close to shopping and other services, perhaps they can get by without a second car. But if they tried to live a normal, middle-class life in other ways—buy an average home, send their younger child to preschool, purchase health insurance, and so forth—they would be left with only $5,500 a year to cover all their other expenses. They would have to find a way to buy food, clothing, utilities, life insurance, furniture, appliances, and so on with less than $500 a month. The modern single-earner family trying to keep up an average lifestyle faces a 72 percent drop in discretionary income compared with its one-income counterpart of a generation ago.

But the biggest change has been on the risk front. In the early 1970s, if any calamity came along, the family had nearly half its income in discretionary spending. Of course, people need to eat and turn on the lights, but the other expenses—clothing, furniture, appliances, restaurant meals, vacations, entertainment and pretty much everything else—can be drastically reduced or even cut out entirely. In other words, they didn’t need as much money if something went wrong. If they could find a way through unemployment insurance, savings or putting their stay-at-home parent to work, they could cover the basics on just 50% of their previous earnings. Because of the option of a second paycheck, both could stay in the workforce for a few months once the crisis had passed, and pull out of their financial hole.

But today’s family is in a very different position. Fully 75 percent of their income is earmarked for recurrent monthly expenses. Even if they are able to trim around the edges, families are faced with a sobering truth: Every one of those expensive items we identified—mortgage, car payments, insurance, tuition—is a fixed cost. Families must pay them each and every month, through good times and bad times, no matter what. Unlike clothing or food, there is no way to cut back from one month to the next. Short of moving out of the house, withdrawing their children from preschool, or canceling the insurance policy altogether, they are stuck.

Today’s family has no margin for error. There is no leeway to cut back if one earner’s hours are cut or if the other gets sick. There is no room in the budget if someone needs to take off work to care for a sick child or an elderly parent. The modern American family is walking a high wire without a net. Their basic situation is far riskier than that of their parents a generation earlier. If anything—anything at all—goes wrong, then today’s two-income family is in big trouble.

The rules have changed

The one-two punch of income vulnerability and rising costs have weakened the middle class, but the revision of the rules of financing is delivering a death blow to millions of families. Since the early 1980s, the credit industry has rewritten the rules of issuing credit to families. Congress has turned the credit industry loose to charge whatever they can get and to bury tricks and traps throughout their credit agreements. Credit card contracts that were less than a page long in the early 1980s now number 30 or more pages of small-print legalese. In the details, credit card companies lend money at one rate, but retain the right to change the interest rate whenever it suits them. They can even raise the rate after the money has been borrowed—a practice once considered too shady for even a back-alley loan shark. When they think they have been cheated, customers in one state are forced into arbitration in locations thousands of miles from home. Companies claim that they can repossess anything a customer buys with a credit card.

Credit card issuers are not alone in their boldness. Home mortgage lenders are writing mortgages that are so one-sided that some of their products are known as “loan-to-own” because it is the mortgage company—not the buyer—who will end up with the house. Payday lenders are ringing military bases and setting up shop in working class neighborhoods, offering instant cash that can eventually cost the customer more than a thousand percent interest.

For those who can stay out of debt, the rules of lending may not matter. But the economic pressures on the middle class—stagnant wages, the need to pull down two salaries to support a family, and the rising costs of the basic expenses—are causing more families to turn to credit just to make ends meet. When something goes wrong—a job loss, an illness or accident, or a family break-up—the only place to turn is credit cards and mortgage refinancing. At that moment, the change in lending rules matters. The family that might manage $2,000 of debt at 9%, discovers that it cannot stay afloat when interest rates skyrocket to 29%. And the family that refinanced the home mortgage into a larger loan may be staring at foreclosure. Job losses or medical debts can put any family in a hole, but a credit industry that has rewritten the rules can keep that family from ever climbing back.

What happens to our middle class?

Family by family, the middle class now faces higher risks that a job loss or a medical problem will push them over the edge. They are working harder than ever just to maintain a tenuous grasp on a middle-class life. Plenty of families make it, but a growing number of those who worked just as hard and followed the rules just as carefully find themselves in a financial nightmare. A once-secure middle class has disappeared. In its place are millions of families whose grip on the good life can be shaken loose in an instant.

Elizabeth Warren is the Leo Gottlieb Professor of Law at Harvard Law School.