Aesop’s familiar fable of the grasshopper and the ant is a story about inequality. The grasshopper is present-oriented, carefree, and lackadaisical; the ant, future-oriented, conscientious, and hardworking. At the end of the summer, the ant is rich with plenty of food for the winter; the grasshopper is poor, facing starvation. The inequality in their material conditions of life reflects the differences in their individual attributes and in their individual efforts.

A quite different parable of inequality is given by Alan Garfinkel in his book Forms of Explanation:1 Garfinkel, Alan. Forms of Explanation: Rethinking the Questions in Social Theory. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 1981. Print. Pg. 41, 43.

Suppose that, in a class I am teaching, I announce that the course will be “graded on a curve,” that is, that I have decided beforehand what the overall distribution of grades is going to be. Let us say […] that I decide that there will be one A, 24 Bs and 25 Cs. The finals come in, and let us say Mary gets the A. She wrote an original and thoughtful final […] If we take each person in the class and ask why that person got the grade he or she did, we have fifty answers to the question why Mary got an A, Bob got a B, […] Harold got a C, but the answers to those fifty questions do not add up to an answer to the question of why there was this distribution of grades.

While Mary is like the ant, which might be a perfectly good explanation for why she in particular got the A, it is clearly an inadequate explanation for the overall inequality in grades in the class. The distribution of grades is not explained by the distribution of attributes and efforts of students, but by the exercise of power by the teacher.

These two stories capture the central intuition of the two dominant approaches to understanding inequality in contemporary capitalist societies. The first approach sees economic inequalities as primarily the result of the attributes and efforts of persons; the second emphasizes inequalities built into the structure of social positions. Of course these two approaches to thinking about inequality often get combined in various ways, but one or the other tends to anchor research.

In what follows, we will first examine the explanatory reasoning of these general perspectives on inequality, and then explore their normative implications. The essay will conclude with a discussion of the connection between these approaches to inequality and the concept of class.

The individual attributes approach

There is something intuitively appealing about the individual attributes approach to inequality. After all, the income distribution is a distribution across persons. It seems natural, therefore, to believe that this distribution is explained by the distribution of other properties across the same individuals—but what properties? Given that in developed capitalist societies, economic status and rewards for most people are acquired mainly through employment in paid jobs, the central question for the individual attributes approach to inequality concerns the process by which people acquire the cultural, motivational, and educational resources that affect their success in labor markets.

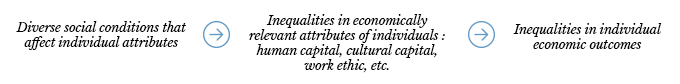

“A range of social factors play a crucial role in shaping such individual market capacities.”While this agenda implies a focus on individuals, it is not necessarily purely individualistic. As countless studies have demonstrated, a range of social factors play a crucial role in shaping such individual market capacities: racial and gender discrimination, the quality of schools, childrearing practices, neighborhood characteristics, and so on. Social causes are thus relevant for explaining inequalities in income and economic status, but they work through the inequalities in the attributes of persons, not directly on the income distribution itself. A simplified picture of this model is given below.

The structural approach

The central idea of structural approaches to inequality is that while the attributes and efforts of persons may explain who ends up in what position, they do not adequately explain the distribution of the positions themselves. The distribution of income and other economic rewards is not simply the aggregate effect of the activities of grasshoppers and ants; rather, it is, to a significant extent, the result of the processes through which jobs with different levels of rewards are created. Among the many aspects of these processes, of particular importance is the way power is exercised in the institutions (especially corporations and the state) that create and regulate jobs.

The fact that the income of CEOs of large corporations is several hundred times that of workers, for example, to a significant extent reflects the power of CEOs to set their own pay in collusion with boards of directors. The precariousness of employment and erratic work schedules of many workers in the fast food industry reflect the weakness of workplace regulations and unions in the sector, and the resulting power of managers to set work schedules as they please. The conversion of a significant proportion of academic jobs from secure tenure-track positions to precarious adjunct positions reflects shifting power relations over state budgets and university politics. And more broadly, the disappearance of large numbers of middle-income jobs in recent decades reflects the power of corporations to shift their capital around the world in ways that maximize the interests of shareholders rather than the welfare of employees.

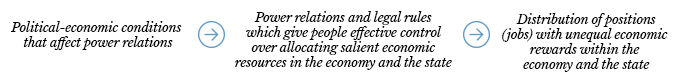

“The creation of jobs with particular characteristics depends on the balance of power among capital, labor, and the state.”Power structures in capitalist economies vary across time and place. Unlike the unilateral creation of the severe grading curve by the professor, the creation of jobs with particular characteristics (e.g., remuneration, security, working conditions, career prospects) depends in significant ways on the balance of power among capital, labor, and the state. All sorts of things affect these power relations. Labor laws can make it easy or difficult for unions to form. State regulation of the workplace affects minimum wages, job security, overtime rules, and other properties of jobs. Globalization and financialization of the economy can undermine the bargaining power of unions. Technological change can fragment the underlying solidarities on which union power depends. The task of a structural view of inequality, then, is to study the ways in which power shapes the distributional characteristics of jobs and the ways in which political-economic conditions affect those power relations. A stripped down version of this idea is illustrated below.

Approaches to inequality and normative concerns

The individual attributes view of inequality is closely allied with the normative ideal of fairness as equal opportunity. The ideal of equal opportunity is realized in the world of Aesop’s fable, where inequalities in well-being are entirely the result of choices for which people can be reasonably held responsible; the grasshopper and the ant are both responsible for their fates. We do not live in such a world because of two salient sources of unequal opportunity. First, people who have acquired the same economically relevant attributes often face different obstacles in the labor market, especially labor market discrimination on the basis of race, gender, and other attributes that have no relevance to an individual’s productivity. Secondly, children clearly face different conditions for acquiring the economically relevant attributes in the first place. In particular, if we want to reduce inequality at the bottom of the income distribution (i.e., reduce poverty) we need to reduce the inequalities in the acquisition of human capital. Mostly this has led to a focus on education as the central way of increasing opportunity: the poor frequently lack the education necessary to get good jobs in contemporary labor markets; the solution is to improve access to good quality education to remedy this deficit.

“Structural approaches to inequality are linked to normative ideals of democracy.”Structural approaches to inequality are linked to normative ideals of democracy. Once we recognize that inequalities across positions in an economic structure do not simply reflect the distribution of individual attributes, but are to a significant extent the result of the exercise of power, then, in addition to the issue of equal opportunity, the distribution of power becomes a salient normative concern. The question of fairness of inequalities is thus not simply a question of the opportunities people have in gaining rewards in the economic system, but of the fairness of who gets to exercise critical forms of power that shape those inequalities.

Capitalist economies always involve highly unequal distributions of power over the allocation of economic resources and governance of production. Indeed, this is what “private” ownership of capital means: owners have the right and power to dispose of their capital as they wish. In recent decades, many of the constraints on this exercise of power by owners of capital have weakened under the banner of neoliberalism: unions have declined, workplace rules have been weakened in the name of flexibility, the geographical mobility of capital has increased, and increasing concentration of capital itself has contributed to increasing concentrations of power. Reversing these trends in the distribution of power is essential if we ever hope to reduce the structural sources of inequality in the distribution of income.

Inequality and class

These two approaches to inequality correspond to two different concepts of class: gradational concepts and relational concepts.

The individual attributes view of inequality is linked to the gradational concept of class. In the gradational concept of class, classes are seen as rungs on a ladder in which classes are always defined as being “above” and “below” other classes. The names of classes reflect this strictly quantitative understanding: upper class, upper-middle class, middle class, lower-middle class, lower class, and underclass. This is the language of class in contemporary discussions about the decline of the middle class and political calls for a “middle class tax cut.” Insofar as attributes of individuals explain where a person ends up in an income distribution, they also explain a person’s class.

“Classes are defined not simply relative to each other, but in a social relation to each other.”The structural view of inequality is linked to relational concepts of class. Here classes are defined not simply relative to each other, but in a social relation to each other. Classes are not arbitrary divisions along a continuum from lower to upper; they get their names from the social relations that bind them together. In the class structure of capitalism, the issue is not simply that workers have less of something that capitalists have more of, but rather that they occupy a specific qualitative position within a social relation that defines both the capitalist class and the working class: the social relations in which workers are hired by capitalists (or their surrogates) who then direct their activities in the workplace.

The connection between the relational view of class and the structural view of inequality is power. In the relational view of class, the core property of the social relations within which classes are defined is power: by virtue of their ownership of the means of production, capitalists have power over workers. This class power, in turn, is at the center of the ways in which power shapes the distribution of economic rewards, both because of the way class power affects state policies that shape the income distribution and because of the ways class power directly affects the earnings connected to different kinds of jobs.

These connections between class and inequality suggest that there is something a bit misleading about the story of the professor grading on a curve at the beginning of this essay. In the story, the distribution of grades is decided by a god-like figure outside of the distribution. If the grading parable was like a real class structure, Mary, at the top of the distribution, would not only get the A, but would also have the power to shape the distribution itself to insure that it conforms to her interests. This, then, in the relational view of class, is the core of the link between class and inequality: the power relations that define a class structure confer on those who benefit most from distributional inequalities the power to shape that very distribution.