During the peak of Islamic State (IS) control over Middle Eastern territory from 2014 to 2016, images of militants smashing statuaries to the ground and targeting the region’s rich cultural heritage were all over the news. In Syria in 2015, IS carried out executions against the backdrop of the ancient site of Palmyra, as well as turning its attentions to destroying the site itself, and those who cared for it. The archaeologist Khaled al-Asad, who, then-Director General of UNESCO Irina Bokova later said, “would not betray his deep commitment to Palmyra,” was publicly beheaded after he refused to direct IS members to the location of hidden artifacts. Palmyra continued to be a focal point of armed struggle as Syrian government forces, with Russian air support, retook the site in 2016. Then, in May, in a performance that wedded Russian cultural prowess with a confirmation of its military power, the Mariinsky Symphony Orchestra played classical music amidst the ruins in a concert simultaneously broadcast on Russian state television and intercut by footage of the Russian military in action.

Palmyra was targeted from all sides for its value as a metaphor, as a backdrop, and as a projection of cultural and military might. The IS took Palmyra back in December 2016, and Syrian government forces did so once again in 2017. A UNESCO World Heritage site, listed for its status as “one of the most important cultural centres of the ancient world … at the crossroads of several civilizations,” Palmyra had found itself at another kind of intersection: where cultural heritage meets violence.

“Heritage is an inheritance—what comes from the past to us today, and what we might pass on to the future.”The term “cultural heritage” encompasses a great range of ways the past manifests in the present: archaeology, artifacts, museums, memorials. As the word suggests, heritage is an inheritance—what comes from the past to us today, and what we might pass on to the future. Importantly, though, heritage is never just these things. As the critical heritage scholar Rodney Harrison puts it, heritage is not “simply preserving things from the past that remain, but an active process of assembling a series of objects, places, and practices that we choose to hold up as a mirror to the present, associated with a particular set of values that we wish to take with us into the future.”1Heritage: Critical Approaches (New York: Routledge, 2012), 4.

Heritage, in other words, is also something we do. We make heritage; people and societies use the material remains of the past for their own purposes, in response to their own needs in the present. This renders heritage a social and political phenomenon that incorporates objects. This heritage-making is subject to all sorts of dynamics, including those that involve violence—not only the physical violence of conflict, but also symbolic and structural violence within society.

Heritage is frequently a material target of violence, as we saw in Palmyra. Here the ancient site was attacked not only for itself, but also for its ability to serve as a metaphor of power and a proxy attack on those who valued it. What happened at Palmyra was dramatic, but far from unique. In Timbuktu in 2012, attacks on religious sites by Ansar Dine were, as ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda put it, not only directed at heritage sites themselves, but at “the soul and spirit of the people.” (Indeed, the leader of this campaign, Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi, was convicted at the ICC in the first instance of a war crimes conviction for the intentional destruction of religious and historical buildings.) Both the ICC and Ansar Dine, like the Taliban who destroyed Afghanistan’s Bamiyan Buddhas in 2001, knew that heritage holds meaning, symbolism, and deep value for communities.

“Conflicts over heritage…are never simply about heritage itself, but rather about its place at the center of social and political dynamics, including those which harness material, symbolic, and structural violence and responses to it.”This makes heritage a welcoming target for those who wish to inflict violence—but it also means that heritage itself can be a vehicle for violence. In the United States, conflicts over the future of Confederate monuments have raised questions about how heritage can both memorialize and perpetuate injustice. Protests centered on these monuments have forced Americans to grapple both with the country’s racist, violent past and present and with the question of who is entitled to make decisions about heritage in the public sphere. This discussion of how public monuments can embody and perpetuate violence is global. Protests have arisen also across Europe, especially focused around statues of brutal colonizers like King Leopold II. In South Africa (and elsewhere), the #RhodesMustFall campaign linked the removal of monuments to Cecil Rhodes to the decolonization of education and confronting structural inequality.2 Zed Books, 2018More Info → Conflicts over heritage, in other words, are never simply about heritage itself, but rather about its place at the center of social and political dynamics, including those which harness material, symbolic, and structural violence and responses to it.

Zed Books, 2018More Info → Conflicts over heritage, in other words, are never simply about heritage itself, but rather about its place at the center of social and political dynamics, including those which harness material, symbolic, and structural violence and responses to it.

Violence also shapes how the heritage we encounter is managed and handled—part of Harrison’s “process of selection.” What do we choose to keep? How do we interpret it? How do people relate to and understand it? The answers to these questions are affected by invisible dynamics of structural violence. Colonial archaeological knowledge production, for example—what Zimbabwean archaeologist Ashton Sinamai calls “pith helmet archaeology”3Ashton Sinamai, “Shadreck Chirikure: Great Zimbabwe: Reclaiming a ‘Confiscated’ Past,” African Archaeological Review 38 (2021): 387–388.—has erased African perspectives on their own history and dominated the interpretation of sites like Great Zimbabwe.4 Routledge, 2020More Info → But critical assessments of these forces have also given rise to attempts to push back with new, indigenized,5

Routledge, 2020More Info → But critical assessments of these forces have also given rise to attempts to push back with new, indigenized,5 Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2012More Info → and decolonized practices of research, management, and interpretation.6Chirikure, Great Zimbabwe.

Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2012More Info → and decolonized practices of research, management, and interpretation.6Chirikure, Great Zimbabwe.

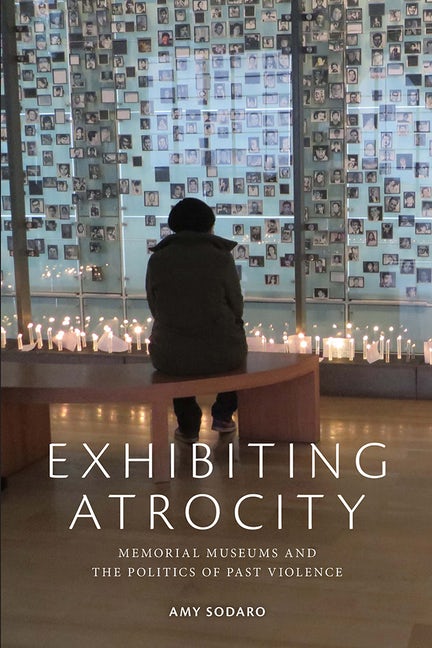

Other instances show how heritage can be a vehicle for not only injustice but also the pursuit of justice in the wake of structural violence. Many museums around the world hold valuable cultural objects—and even human remains—taken from Indigenous and colonized peoples. But today, claims by communities for such heritage’s repatriation, from Native America7Russell Thornton, “Repatriation and the Trauma of Native American History,” in The Routledge Companion to Indigenous Repatriation: Return, Reconcile, Renew, eds. Cressida Fforde, C. Timothy McKeown, Honor Keeler (Routledge, 2020). to postcolonial Nigeria, seek to counter the enduring violence of colonialism8Ciraj Rassool, “Re-storing the Skeletons of Empire: Return, Reburial and Rehumanisation in Southern Africa,” Journal of Southern African Studies 41, no. 3 (2015): 653–670. and the deep wounds such museum collections have inflicted by removing heritage from the people to whom it is most meaningful. The memorialization of violent atrocity, as at genocide memorials, displays similarly multifaceted characteristics. Genocide memorials are usually designed to honor the memory of victims, are meant to promote human rights in the context of transitional justice,9 Cambridge University Press, 2020More Info → and play a complex role in recognizing the trauma of survivors.10Rachel Ibreck, “The Politics of Mourning: Survivor Contributions to Memorials in Postgenocide Rwanda,” Memory Studies 3, no. 4 (2010): 330–343. They can also be a site of contestation in contemporary politics.11

Cambridge University Press, 2020More Info → and play a complex role in recognizing the trauma of survivors.10Rachel Ibreck, “The Politics of Mourning: Survivor Contributions to Memorials in Postgenocide Rwanda,” Memory Studies 3, no. 4 (2010): 330–343. They can also be a site of contestation in contemporary politics.11 New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2018More Info →

New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2018More Info →

The politics, both domestic and international, of the heritage-violence intersection are particularly fraught. Physical violence directed at heritage raises a set of questions about whether this can be seen as a form of cultural genocide, or if it triggers a responsibility to protect.12Thomas G. Weiss and Nina Connelly, “Cultural Cleansing and Mass Atrocities: Protecting Cultural Heritage in Armed Conflict Zones,” J. Paul Getty Trust Occasional Papers in Cultural Heritage Policy, no. 1 (2017). Might violence directed at heritage be part of the project of governing people and territory through asserting control over them, as political scientist Oumar Ba argues?13Oumar Ba, “Governing the Souls and Community: Why Do Islamists Destroy World Heritage Sites?” Cambridge Review of International Affairs, June 30, 2020. Do attacks on heritage even indicate that violence against people is imminent, in an echo of Heinrich Heine’s famous line, “Where they burn books, they will also ultimately burn people”? Such violence has repercussions long after the crisis has ended. What to make of the prospect of reparations14Luke Moffett, Dacia Viejo Rose, and Robin Hickey, “Shifting the Paradigm on Cultural Property and Heritage in International Law and Armed Conflict: Time to Talk about Reparations?” International Journal of Heritage Studies 26, no. 7 (2020): 619–634. or of projects of reconstruction, like UNESCO’s efforts to rebuild destroyed Iraqi heritage in the wake of the United States’ war in that country?15Benjamin Isakhan and Lynn Meskell, “UNESCO’s Project to ‘Revive the Spirit of Mosul’: Iraqi and Syrian Opinion on Heritage Reconstruction after the Islamic State,” International Journal of Heritage Studies 25, no. 11 (2019): 1189–1204. These efforts are far from a simple restoration of heritage; instead, especially given the involvement of international experts and funders, they force us to consider how heritage projects can engage—or not—with the needs of local communities that have suffered violence and loss.

As this inexhaustive recounting shows, many questions persist about the entanglement of heritage and violence, broadly construed. In this essay series, scholars from around the world take them on. Their essays demonstrate how studies of heritage can shed light on issues from the physical violence of war to the structural violence of colonialism and exploitation to the legacies of violence in the years that follow.

“Heritage’s value and meaningfulness in the world are revealed by its place within the forces of—sometimes violent—contestation.”The series opens with an assessment of “responsibility to protect,” and whether incorporating the protection of cultural heritage into this framework is warranted in order to protect people and things from violence. Over the next weeks, essays in this series will address the marketing of “cannibal” histories in auctions of Oceanic artifacts, local voices on the destruction and reconstruction of heritage in Iraq and Syria, ongoing erasure and destruction at Japanese internment camps in the United States, and other topics. If cultural heritage indeed designates more than simple objects, we can consider it, as these essays do, in many different lights: as a social phenomenon, as a subject or even a driver of political forces, as a tool, and as a part of people’s identities. Heritage’s value and meaningfulness in the world are revealed by its place within the forces of—sometimes violent—contestation. And heritage itself can show us the violence of both the past and the present; in engaging with it, we negotiate what our societies become.

Banner photo: ian262/Flickr.