Ten years ago, at the end of 2011, a woman grabbed my arm to pull me into a procession snaking its way through central Hadiboh, the capital of Socotra. A year into the Arab uprisings, the streets of Hadiboh resembled the streets of Arab cities almost everywhere. A “revolutionary tent” modeled after the protest encampments in Tahrir Square (Cairo) and Taghyir Square (Sanaa) had been erected near the central soccer pitch. Hadiboh’s youths had taken it upon themselves to clean up the town’s ubiquitous plastic litter in an act of self-governance and as an indictment of state neglect. And protestors of all backgrounds—fed up with corruption, price hikes, and the reduction in affordable air travel between Socotra and mainland Yemen—chanted slogans demanding local administrative change and national political reform. One rhyme they returned to over and over was: “Revolution, revolution in all of Yaman, from Socotra to ‘Amran!” An Indian Ocean island 240 miles south of the Arabian Peninsula, Socotra is about as distant from the northern governorate of ‘Amran as one can be within Yemen. As I wrote at the time,1Nathalie Peutz, “Revolution in Socotra: A Perspective from Yemen’s Periphery,” Middle East Report 263 (Summer 2012): 14–20. “In Hadiboh, so removed from Yemen in so many ways, this vow of unity was electrifying.”

”What started as a largely peaceful revolution despite Yemen’s heavily armed tribes—in Socotra, as elsewhere in Yemen, protestors wore pink to signal their nonbelligerent intent—has turned into a protracted civil-and-proxy war claiming nearly a quarter million lives.”Today, it is Yemen’s disunity that resounds throughout the country. In February 2012, Yemen’s ousted president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, ceded power to his deputy, former vice president Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, the sole candidate in an election boycotted by Houthi rebels in the north and secessionists in the south. Three years later, in January 2015, President Hadi resigned after Houthi forces had taken control of Sanaa and much of northern Yemen with the help of Saleh, their erstwhile foe. In March 2015, Saudi Arabia and a coalition of Arab-majority states launched Operation Decisive Storm to unseat the Houthis and restore Hadi’s government to power, with US intelligence and logistical support. Originally expected to last for less than six months, the ongoing military intervention has engendered the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. Today, more than 20 (out of 30) million Yemenis are in need of humanitarian assistance, five million Yemenis are at risk of famine, and more than four million Yemenis are internally displaced.2David Gressly, “United Nations Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for Yemen, David Gressly Remarks to Media in Geneva,” United Nations Office of the Resident Coordinator and the Humanitarian Coordinator for Yemen, October 11, 2021. What started as a largely peaceful revolution despite Yemen’s heavily armed tribes—in Socotra, as elsewhere in Yemen, protestors wore pink to signal their nonbelligerent intent—has turned into a protracted civil-and-proxy war claiming nearly a quarter million lives.

In addition, hundreds of thousands of Yemenis fled the country, largely by way of small dhows and fishing boats crossing the Red Sea. Those who had the means and opportunity to travel onward joined relatives in the diaspora or sought asylum elsewhere. Others displaced by fighting and airstrikes in western Yemen fled to neighboring Djibouti and Somaliland and stayed, having been recognized there as refugees on a prima facie basis. A good percentage of these refugees are the biracial descendants of Yemeni men who had once migrated to and married women from the Horn of Africa and thus had relatives or social connections there already. However, this route to becoming and understanding themselves as refugees was a new one for Yemenis who had understood themselves to be citizens of—or even migrants from—a country that had generously hosted refugees from the Horn of Africa, but not one that had engendered them. With the war, Yemen has become a refugee-producing country, too.

In this essay, I reflect on the changing aspirations of some of the many Yemenis who had been alienated in Saleh’s Yemen. During the revolution, Socotran islanders who had long felt like second-class citizens on account of their ethnic, linguistic, and geographic marginalization believed that they could aspire to more: that full citizenship and a life of dignity was finally within reach. During the war that followed, and that is now entering its seventh year, many Yemeni mainlanders who had long felt discriminated against on account of their ethnic, racialized, or low occupational status are no longer hoping to be treated as full citizens but as full refugees. While this juxtaposition has its flaws—Socotrans consider themselves an ethnic minority within Yemen while the Yemeni refugees are, of course, a diverse population constituted through a shared legal category—I propose that this aspirational decline from “citizen” to “refugee” captures some of the hopes and disappointments of the post-revolutionary period. It may also structure our scholarship for years to come.

The revolution in Socotra

Socotra is the largest island of Yemen’s Socotra Archipelago, one of the most biologically diverse island chains in the world. For years, I had been researching and documenting Socotra’s transformation from a geographically and socioeconomically marginalized region of Yemen into a national protected area, a UNESCO natural World Heritage Site, and an ecotourism attraction.3 Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018More Info → I had first visited Socotra in March 2003 during the US invasion of Iraq; then, I followed the events unfolding in Iraq through broadcasts from my pastoralist hosts’ shortwave radio. A year later, while residing among pastoralists in one of the newly established nature sanctuaries, I discovered how weary my interlocutors were of unrest (fitna) at home. Middle-aged Socotrans who had lived through several distinct political systems and regime changes already—a Sultanate under British occupation, socialist South Yemen (1967–1990), and the then-unified democratic Republic of Yemen (1990–2015)—extolled the virtues of their island’s security (‘amn) while worrying about how their increasing connectivity to the mainland would impact them.

Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018More Info → I had first visited Socotra in March 2003 during the US invasion of Iraq; then, I followed the events unfolding in Iraq through broadcasts from my pastoralist hosts’ shortwave radio. A year later, while residing among pastoralists in one of the newly established nature sanctuaries, I discovered how weary my interlocutors were of unrest (fitna) at home. Middle-aged Socotrans who had lived through several distinct political systems and regime changes already—a Sultanate under British occupation, socialist South Yemen (1967–1990), and the then-unified democratic Republic of Yemen (1990–2015)—extolled the virtues of their island’s security (‘amn) while worrying about how their increasing connectivity to the mainland would impact them.

Indeed, the introduction in 1999 of regular, commercial flights between Socotra, Sanaa, and Aden had enabled not only Socotrans to reach mainland hospitals for critical medical care. It also precipitated the influx of northern Yemeni merchants and their imports, including qat, a leafy narcotic that the Socotran “revolutionaries” (their term) sought to banish from the central marketplace in 2011; mounting land disputes; and (according to Socotrans) increasing factionalism. Despite Socotrans being citizens of Yemen, many viewed this “northern” incursion as a form of colonization by wealthy and well-connected mainlanders who were buying up their land. Moreover, Socotrans who had come of age during the socialist period had learned to be ashamed of their Indigenous, unwritten language (Suqutri), which had been treated as a poor dialect of Arabic. Now, with the “opening” of the island to development, Socotrans were becoming increasingly embarrassed also by their relative impoverishment, their pastoralist (“Bedouin”) upbringing, and their purportedly ignorant customs. Most Socotrans I knew avoided “entering [talking] politics,” for fear of causing social strife. One had to listen between the lines of Suqutran poetry to know how many Socotrans were feeling alienated, disempowered, and dispossessed.4Nathalie Peutz, “Bedouin ‘Abjection’: World Heritage, Worldliness, and Worthiness at the Margins of Arabia,” American Ethnologist 38, no. 2 (2011): 338–360.

Of all the changes I witnessed in Socotra in the decade between 2003 and 2013, by far the most striking were the expressions of empowerment the uprisings ushered in. Socotrans whom I had known to be politically disengaged and circumspect had begun joining public demonstrations and openly expressing their grievances. Many Socotrans were individually and collectively refusing silence; refusing to feel ashamed of their mother tongue; refusing to accept Yemen’s caste-like social distinctions based on genealogy, race, and occupation; refusing corrupt or ineffective local leadership; simply “refus[ing] to continue on this way.”5Carole McGranahan, “Theorizing Refusal: An Introduction,” Cultural Anthropology 31, no. 3 (2016): 319–325. “Now the reins of power are in the hands of the people,” Yahya, a Socotran friend, had said while apprising me in January 2012 of the revolutionaries’ recent effects to “purify” the local government. “We’ll go after any sign of corruption, any director who doesn’t work out…. And then, that’s it. He leaves, he leaves [yirhal].”

Notably, for all the activists’ talk of self-determination and the value of their Suqutri language and traditions, this mode of self-expression had been imported, too. “We’ve benefitted from this Arab spring,” Yahya continued. “Irhal [leave], isqat an-nizam [topple the regime]—these are new words we didn’t know before. The revolutions brought this talk and, thank God, Socotran society is beginning to understand, to acquire civilization, to change by itself.” Later, Yahya articulated what these successes had meant for him—a Socotran of African descent in a context where some Africans had been enslaved until the 1960s–personally: “Now, thank God, I feel as if I’m a free citizen. I feel inside that I am a citizen who is free. Noble! I don’t feel afraid like I did before. I speak from strength, and I’ll press my demands until they are realized.”

”In Socotra, demonstrations against the regime continued, as did voluntary acts of self-governance.”For a few short years, Yahya’s sense of emancipation seemed optimistic but warranted. In Socotra, demonstrations against the regime continued, as did voluntary acts of self-governance. Several youth groups formed specifically to fill the void left by the withdrawal of international NGOs and the suspension of foreign aid: by initiating island cleanups and environmental awareness campaigns, for example. In March 2013, Socotra sent three delegates to Sanaa to participate in the National Dialogue Conference (2013–2014), a representative forum tasked with facilitating Yemen’s reconciliation and with formulating the basis for a new constitution. Not all Socotrans were supportive of these Sanaa-directed proceedings, but the Dialogue resulted in some triumphs, especially pertaining to the archipelago. In December 2013, Yemen’s transitional government decreed that the Socotra Archipelago had been elevated to a governorate. And Yemen’s draft constitution, finalized on January 15, 2015, contained a prominent state commitment (in Article 3) to protecting Yemen’s minority languages: Mehri and Suqutri. However, within a week of the draft constitution’s release, the country fell into its current crisis of government and this interminable war.

The last time I visited Socotra was in December 2013. Since then, I have kept in touch with my former interlocutors and hosts through WhatsApp and periodic phone calls. For millions of Yemenis, including Socotrans, the Saudi-led and US-supported aerial bombardment of Yemen and embargo of its airspace has been life-threatening. Even those whose villages, schools, homes, markets, hospitals, and fishing boats have not been hit by airstrikes, suffered and continue to suffer from the aerial and naval blockades. On Socotra, which has not been targeted, this aerial “siege” (as Socotrans called it) has resulted in shortages of imported foods, medicines, and cooking gas. Many Socotrans lost their incomes while others were unable to travel to the mainland for urgent medical treatment, like dialysis.6Likewise, Yemenis on the mainland were unable to travel abroad for critical medical care unavailable in Yemen. In December 2016, an overloaded cargo vessel carrying 64 passengers from al-Mukalla to Socotra capsized at sea and around 30 Socotrans drowned. Commercial flights had resumed briefly in spring 2016 only to be suspended again through most of 2018. When flights recommenced, they were infrequent and often canceled, leading Socotrans to resort to irregular sea travel instead.

Despite Socotrans’ war-induced confinement, the island has not been shielded from the conflict. In November 2015, within months of having become cut off from mainland Yemen, it was struck by back-to-back cyclones. Together, cyclones Chapala and Megh destroyed or damaged more than 800 homes and displaced more than 10,000 people. In response, the UAE’s Khalif bin Zayed Al Nahyan Foundation and Saudi Arabia’s King Salman Humanitarian Aid and Relief Centre sent several hundred tons of food supplies and other relief aid to Socotra by boat and by air. By spring 2018, both the UAE and Saudi Arabia had deployed their troops to the island, provoking talk of occupation, if not yet another colonization. More recently, in June 2020, Yemen’s secessionist Southern Transitional Council seized control of the island deposing the local Saudi-backed governor. Today, Socotra is divided into pro-Emirati, pro-Saudi, and various other factions. One thing Socotrans are likely to agree upon is that the mainland’s fitna has arrived there, too.

The making of Yemeni refugees

In the intervening years, unable to return to Socotra, I have taken up a new research project on Yemeni refugees and migrants in the Horn of Africa.7Nathalie Peutz, “‘The Fault of Our Grandfathers’: Yemen’s Third Generation Migrants Seeking Refuge from Displacement,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 51, no. 3 (2019): 1–20. The bulk of my fieldwork to date has been conducted in Djibouti, one of few countries that granted prima facie refugee recognition to all Yemenis fleeing from Yemen. Djibouti is also the only country to have established a camp for refugees from Yemen: Markazi, where some of Yemen’s most vulnerable refugees reside. Like many Socotrans I know, these are Yemenis who had felt marginalized within Yemen—not because of their geographic location or linguistic identity, but because of their perceived blackness or low status within the country’s hierarchical, caste-like social system. In Yemen, citizens born to a Yemeni father and an African mother—a common occurrence given historical migration patterns across the Red Sea and Yemen’s proximity to the Horn of Africa—are called muwaladeen (“half-caste”), a derogatory label that marks them as impure. Other racialized minorities such as the muhamesheen (“marginalized”; formerly called akhdam, meaning “servants”) are restricted by social norms to menial occupations and are prohibited from owning land or carrying weapons on account of being stigmatized as “weak” and socially “incomplete” (naqis).8Gokh Amin Alshaif, “Black and Yemeni: Myths, Genealogies, and Race,” in POMEPS (The Project on Middle East Political Science) Studies 44 – Racial Formations in Africa and the Middle East: A Transregional Approach (George Washington University, September 2021). The current war has exacerbated these status distinctions and other identity-based labels.9Sabria al-Thawr, “Identity and War: The Power of Labeling,” in POMEPS (The Project on Middle East Political Science) Studies 44 – Racial Formations in Africa and the Middle East: A Transregional Approach (George Washington University, September 2021).

Thus, many of the refugees in the camp today experienced their refugee status as an ascendant status—not only because today’s prized refugee status remains one of the few pathways to the Global North,10→Roger Zetter, “More Labels, Fewer Refugees: Remaking the Refugee Label in an Era of Globalization,” Journal of Refugee Studies 20, no. 2 (2007): 172–192.

→Rebecca Hamlin, Crossing: How We Label and React to People on the Move (Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2021: 7). but also because it puts a name to their sense of alienation at home. Several of the Yemenis living in Markazi maintain that, despite the camp’s undeniable hardships, they have acquired more “rights” as refugees than they had had as Yemeni citizens in Yemen. After all, the Markazi camp has been generously supported by international and local humanitarian organizations as well as Gulf-based charities, including Saudi Arabia’s King Salman Humanitarian Aid and Relief Centre. “At least here, even if we are living in windstorms and heat and tents, at least I feel as if I’m a human being,” Ahmed, a truck driver from Yemen’s Red Sea coast, told me in October 2017. “People come from Europe, America, Ethiopia, and all the organizations to check whether my water is clean or not, to inspect our health, and so on,” he explained. “Back in Yemen, no one would look after us because I’m not a tribesman or the son of a shaykh or a merchant. In Yemen, they look after whom? After those with power and influence. If you’re poor, you’re marginalized. You have no value.”

Frequently denigrated in Yemen—“yā khādim (servant), they’d say”—Ahmed told me a few months later how he had long hoped to leave Yemen. “But no country would have taken me as a refugee—the United Nations wouldn’t have taken me. It would’ve said, ‘there’s no war in your country.’ And yet, war was inevitable. In Yemen, we were suffering. Many Yemenis, millions of them, including me, were suffering […] I felt as if I wasn’t a human being, as if I wasn’t even Yemeni. I was [like] a refugee in Yemen, but without international recognition. A virtual refugee. Now I’m a real refugee.”

The fortunate?

Ten years after Yemen’s “Pink Revolution,” these are just two of the many stories of hope and resignation that stick with me: Yahya, a Socotran of African descent, feeling like he had finally become a “free citizen” in 2011; Ahmed, a self-identified “dark-skinned” man from a “weak” tribe (he rejects the label muwallad or muhamesh) relieved to finally be recognized as a “real refugee” six years later. For all their hardships and disappointments—and I am referring to people who lost their homes to missiles or air strikes or cyclones; some of my interlocutors have had to bury their children due to this war—the previously marginalized Socotrans and the Markazi refugees may end up being the more fortunate ones. Their lives are being sustained by the humanitarian organizations of the Gulf states fighting in the war: a cruel irony that is not lost on them. But they are not among the millions of Yemenis who are starving: Yemenis who can no longer afford to flee across the sea.

Where does this leave scholars who are from or were working on Yemen? Clearly, academic scholarship on Yemen has been one of the numerous casualties of this war. Many Yemeni scholars have left the country, if they could, or are laboring under near-impossible conditions with limited electricity and internet access and steeply rising food costs due to the devaluation of Yemen’s currency. Few non-Yemeni scholars have been able to visit, much less conduct research in Yemen. Nevertheless, a growing cohort of young academics from all backgrounds is now conducting research with Yemeni refugees outside of the country. One result of this emerging scholarship will inevitably be a new spotlight on Yemen as a refugee-producing country—in contrast to an earlier focus on its role as a refugee-hosting country. Meanwhile, much of today’s academic work on Yemen, regardless of its focus, has become infused with an urgent, if not a despairing, tone. It implores readers to concern themselves with this calamity of unfathomable proportions that few scholars could have foreseen in the heady days of 2011.

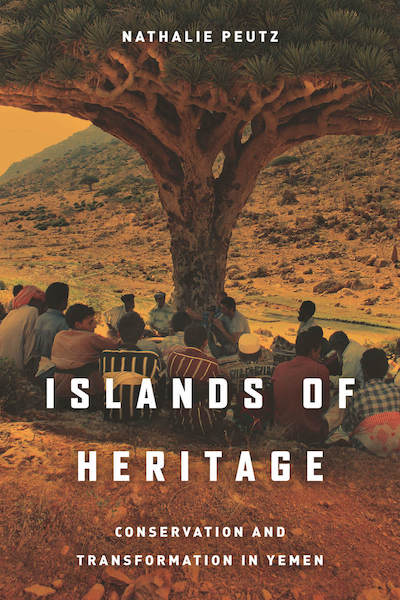

Banner photo: “Revolution in all of Yemen,” Demonstrations in Hadibo, Socotra in January 2012. Photo credit: Nathalie Peutz.

References:

→Rebecca Hamlin, Crossing: How We Label and React to People on the Move (Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2021: 7).