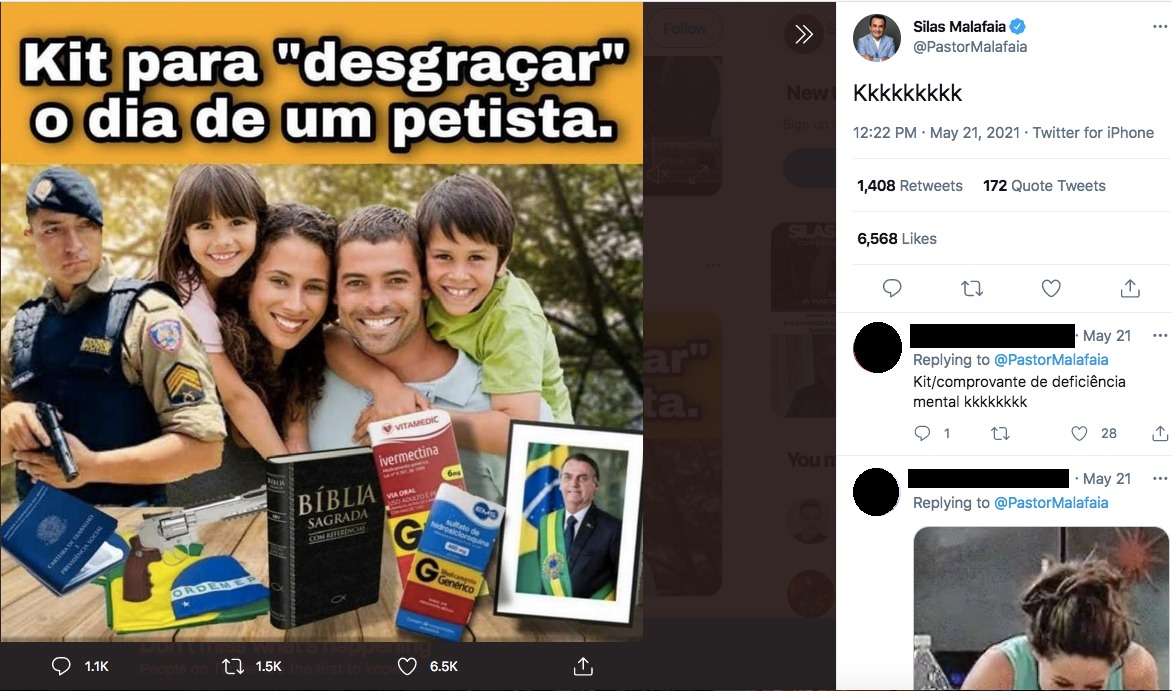

The image above, published by Pastor Silas Malafaia—a well-known Brazilian televangelist—on his social media accounts, summarizes the contemporary evangelical universe in its most visible version, that of religious leaders with great influence in media and the state.1It should be noted that the Brazilian evangelical world is heterogeneous. Although the most visible evangelical leaders can be defined as conservative, there are leaders considered progressive or left-wing expanding their public participation. In addition, while the most visible evangelical leaders are mostly white men, most evangelical believers are women (58 percent) and Black people (59 percent), with low income and low education, according to the Datafolha Institute. For the progressive evangelical leadership, see Gustavo de Alencar, “Grupos protestantes e engajamento social: uma análise dos discursos e ações de coletivos evangélicos progressistas,” Religião & Sociedade 39, no. 3 (2019): 173–196 (2019); Christina Vital da Cunha, “Irmãos contra o império: evangélicos de esquerda nas eleições 2020 no Brasil,” Debates do NER, no. 39 (2021): 13–80. Indeed, the elements in the image repeat a narrative conveyed by evangelical churches and leaders in the media during the Covid-19 pandemic in Brazil and beyond.2Olívia Bandeira and Brenda Carranza, “Reactions to the Pandemic in Latin America and Brazil: Are Religions Essential Services?” International Journal of Latin American Religions 4, no. 2 (2020): 170–193.

The image features what the caption calls a “Kit to upset the day of a petista,” referring to supporters of the Workers’ Party (PT) and also used to refer to the left in general. It promoted the use of drugs not recommended by health authorities, known as the “Covid kit,” the Bible, the Brazilian flag, a revolver, an Employment Record Book,3This is a work and social security card issued by the Ministry of Labor and mandatory for the provision of professional services in Brazil. a picture of far-right president Jair Bolsonaro, and a military policeman with a gun in his hand.

These components appear to surround or protect the idea of the heteronormative family exemplified by the one shown smiling in the center of the image. They synthesize how part of the evangelical leadership has placed themselves in the public arena during the pandemic, advocating individual freedom of movement and opening churches despite lockdown rules, the use of unproven medicines, support for Bolsonaro’s actions, and the strengthening of the idea of Brazil as a “Christian nation” (and no longer a country of Catholic tradition or a religiously diverse country).4According to IBGE (2010 Census), between 1940 and 2010, the number of evangelicals (Protestants, Pentecostals, and Neo-Pentecostals) increased from 2.6 percent of the Brazilian population to 22.2 percent, while the number of Catholics dropped from 95 percent to 64.6 percent in the same period. In 2020, the Bolsonaro government canceled the census scheduled for that year. However, a survey by the Datafolha Institute published in January 2020 points out that evangelicals were already 31 percent of the population, with 50 percent of Brazilians declaring themselves Catholic. The institute estimated that evangelicals could outnumber Catholics and become the majority faith in the country by 2032. The country’s minority religions include Afro-Brazilian religions, Spiritism, Indigenous traditions, Islam, Judaism, and traditions defined as “New Age.” To understand the complex religious dynamics in Brazil, see Faustino Teixeira and Renata Menezes, Religiões em movimento: o Censo de 2010 (Voices Publisher, 2014).

Our research has identified and analyzed the role religious institutions played in the responses to the pandemic in Brazil, focusing on the discourses spread by Christian religious leaders (both evangelical and Catholic) through mass media and social media. We monitored religious programs aired on national TV networks, five religious radio stations, and the social media accounts of religious leaders with high public exposure, over two periods. The first, from October 2020 to January 2021, focused mainly on discourse about the vaccine, announced in 2020 but not administered until January 2021. The second, from February to April 2021, focused on the controversy that arose in relation to a lawsuit filed by the National Association of Evangelical Jurists in the Federal Superior Court requesting that states and municipalities be prohibited from temporarily closing churches as a way to contain the pandemic in their areas. In addition, we collected stories published in traditional media on the actions carried out by religious leaders in public spaces, such as meetings with the president and prayers held in front of public buildings.

During the pandemic, Christian churches with the necessary financial and technological resources intensified an existing practice: the use of mass media and new information and communication technologies to maintain their connection with their followers. In addition to emotional and spiritual support, however, the churches were one of the main voices present in the public discourse concerning the pandemic’s handling.

Religious media in Brazil: From redemocratization to the management of the pandemic

The media and political strengthening of evangelical churches in Brazil has been taking place since the 1980s, during the redemocratization process following the military dictatorship (1964–1985). At the time a minority (6.6 percent of the population in 1980), evangelical leaders participated in the writing of the 1988 constitution with the aim of undermining the historical role of the Catholic Church.5For many decades, evangelicals in Brazil had remained “separated from the world” and politics. However, since the 1980s, political participation grew exponentially. On the involvement of evangelicals in the 1987 constituent assembly and the 1989 presidential elections, see Paul Freston, “In Search of an Evangelical Political Project for Brazil: A Pentecostal ‘Showvention’,” Transformation 9, no. 3 (1993): 26-32. Since then, the number of evangelical representatives in the National Congress and other parts of the state has increased. During this period the number of radio and TV stations controlled by the evangelicals also increased. Today, among the more visible evangelical leaders are precisely those who have positioned themselves in the media, inspired and trained by US televangelism, such as Malafaia from the Pentecostal Assembly of God Victory in Christ (Assembleia de Deus Vitória em Cristo); Edir Macedo from the transnational neo-Pentecostal Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus) and owner of the communication conglomerate Record, the second largest in the country; and R. R. Soares from the neo-Pentecostal International Church of the Grace of God (Igreja Internacional da Graça de Deus).

“Between March and July 2020…the pandemic was heavily covered in religious media, especially the controversy surrounding the closing of places of worship as a means to contain the virus.”From October to December 2020, the monitoring of social media accounts of religious leaders and religious TV and radio programs showed a lack of information about the pandemic, as if Brazil were not one of the countries most affected by the virus. In general, their posts were motivational messages with Bible quotes and church service broadcasts. Content about the pandemic was rare during this period in the religious media surveyed.6It must be said that in the last months of 2020 Brazil saw a drop in the number of people infected or killed by Covid-19. The numbers started to rise again in March 2021. This does not mean that the topic had not been addressed before. Between March and July 2020, as research by Olívia Bandeira and Brenda Carranza shows,7Bandeira and Carranza, “Reactions to the Pandemic in Latin America and Brazil.” the pandemic was heavily covered in religious media, especially the controversy surrounding the closing of places of worship as a means to contain the virus.

Basically, evangelical churches did not promote information campaigns that emphasized social distancing measures and other guidelines that followed health agencies’ recommendations. On the contrary, even when someone from a religious organization had been infected, evangelical leaders omitted the cause. Pastor Malafaia has used this ploy on two occasions: when he excluded the cause of death in notes of condolence on his Facebook and Twitter profiles following the deaths of a cousin and another pastor, both victims of the coronavirus.

This tendency to omit information related to Covid-19 reveals how the Bolsonaro government’s discourse of minimizing the pandemic has a safe harbor and reverberates strongly among sectors of the Brazilian evangelical community. The silence surrounding the pandemic seeks to preserve the idea that nothing has changed, that there’s no pandemic, increasing pressure on the opening of businesses and churches. In this sense, omission would produce an effect similar to denial, in that both approaches question the severity of the situation, posing a false dichotomy between saving lives and saving the economy.

“The president is also looking to evangelicals, a growing segment of the electorate, who helped elect him in 2018, for the political support needed to stay in power in the face of the country’s biggest crisis…”Indeed, the close relationship between evangelical leaders and President Bolsonaro is often exploited by churches. Another media pastor, Josué Valandro Jr., from the Attitude Baptist Church (Igreja Batista Atitude), displayed his role in this alliance through the media, sharing livestreams during the pandemic in which he appears with the Bolsonaro family. His church is known to be attended by First Lady Michelle Bolsonaro. The president is also looking to evangelicals, a growing segment of the electorate who helped elect him in 2018,8Ronaldo de Almeida, “Bolsonaro presidente – conservadorismo, evangelismo e a crise brasileira,” Novos Estudos 38, no. 1 (2019): 185–213. for the political support needed to stay in power in the face of the country’s biggest crisis, with more than 673,000 Covid-19 deaths as of July 11, 2022.9It is worth noting that Bolsonaro was raised Catholic, but got married in an evangelical church under the blessing of Pastor Silas Malafaia and was baptized in the Jordan River, in Israel, by another Brazilian pastor. Although evangelicals support him, Catholics leaders and rabbis also supported Bolsonaro at the beginning of the pandemic, as shown in a Easter 2020 livestream, broadcasted by TV Brasil, a public broadcaster. The livestream was attended by Bolsonaro and 20 Christian religious leaders (17 evangelicals and 3 Catholics), in addition to a rabbi. As Bandeira and Carranza show, when interpreting the pandemic religiously, these leaders sought to: a) strengthen the legitimacy of religion in politics and themselves as spokespersons for a heterogeneous religious field, b) consolidate the image of Brazil as a “Christian nation,” and c) reinforce the religious character in the president’s decisions, elevating him to the “new messiah” ready to save Brazil.10Olívia Bandeira and Brenda Carranza, “Só o Brasil cristão salva do COVID-19?” Boletim Cientistas Sociais, no. 33 (2020).

The churches’ relationship with the president creates a win-win arrangement. For the former, the relationship with Bolsonaro aims at confirming the importance of a particular congregation in the evangelical community, showing how close they are to the highest level of political power, and consolidating its political-religious project for the country. Although evangelical leaders have pragmatically participated in previous presidential administrations, including left-wing governments, it was with Bolsonaro that their moral agenda of defending the heteronormative family and opposing the rights of women and the LGBTI+ people came to power. For the government, this relationship aligns the administration with the interests of a part of the evangelical movement. Evangelical support for Bolsonaro is extremely valuable, since a contingent of these voters—together with the military, business, and agribusiness sectors—form his government’s political base, which has been called “Bolsonarism.”

Web of disinformation

The emergence of the vaccine, however, has returned the pandemic to religious media. There has been plenty of criticism and conspiratorial accusations regarding the vaccine’s effectiveness and the real intention behind its mass administration on social media accounts of religious leaders and on religious TV and radio programs. The narratives about the vaccine given by the most visible evangelical leaders have shifted with government action or inaction, ranging from conspiracy theories and anti-China xenophobia to support for government purchases of vaccines. Conflicting narratives create a web of disinformation with inconsistent stories, the spreading of “fake news,” and conspiracy theories. In this process, we observed that the discourse initially created by Bolsonaro or the religious leaders that support him is reproduced in the radio and social media of less well-known conservative evangelical leaders.

Regarding the vaccine, the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God has gone as far as to broadcast on television, as well as its social media, a conspiracy theory about the “Great Global Reset.” In this eschatological narrative, the “Great Reset” would be one of the first acts of the Apocalypse described in the Bible. In the video, the preacher claims that the Covid-19 vaccines would serve as tools for population control.

Pastor Malafaia continued the attacks on the vaccines. In particular, he used his social media profiles to speak out against the CoronaVac vaccine, produced by the Butantã Institute (a Brazilian biologic research center affiliated with the São Paulo State Secretariat of Health) in partnership with the Chinese biopharmaceutical company Sinovac Biotech. He claimed, referencing President Bolsonaro’s earlier statements, that “the Brazilian people will become guinea pigs.” His objection rested on two points. The first concerned the vaccine’s “suspicious” Chinese origin, because it was claimed that the virus originated in that country. In addition, the pastor hinted that China did not have the technological capability to create a safe and effective vaccine. The second point concerned the mandatory vaccination, fueling mistrust around the intentions of using the Chinese-Brazilian vaccine.11Research shows that, in Brazil, confidence in Covid-19 vaccines grew as vaccination progressed. Distrust in vaccines was greater among men and in the Midwest region, coinciding with the profile of the Bolsonaro electorate. In October 2021, 35.4 percent of respondents with an objection to vaccines surveyed by Morning Consult said they would not be vaccinated if the available formulation had been produced in China. See Rodrigo de Oliveira Andrade, “Confiança nas vacinas,” Pesquisa, November 2021.

Behind the mistrust over the vaccine lurked political disputes. The clashes between Bolsonaro and the governor of São Paulo, João Dória (PSDB), the main sponsor of the CoronaVac vaccine and, at the time of research, a potential candidate for the presidency in 2022,12Governor João Dória withdrew his candidacy for the president in the face of pressure from his party, the Brazilian Social Democracy Party. disrupted the vaccination process. The stance of evangelical groups toward the vaccine changed over time, as vaccination rates increased and the president was forced to adjust his statements in favor of immunization. Evangelical leaders, and their media outlets, adjusted their messaging accordingly.

In March 2021, for example, in the Disque M program, on Melodia FM radio station, run by evangelicals in Rio de Janeiro, the host defended the use of the vaccine, but blamed international demand for the low number of doses available in Brazil. Statements like this aligned with those from the Presidential Palace, which deny accusations that it boycotted or neglected purchase vaccines in 2020. However, a Parliamentary Inquiry Commission opened by the National Congress to investigate the government’s handling of the pandemic proved the Bolsonaro administration created a series of obstacles for the purchase of vaccines, delaying the beginning of its application.

Despite this change in discourse, the vaccine mistrust promoted by political and evangelical leaders helps reinforce the “Sinophobia” that has taken over part of the Brazilian public, especially those aligned with Bolsonarism. They believe that the virus and vaccine are a Chinese strategy to take over global geopolitical control, ultimately carrying out a plan of communist domination.

“Even as the national vaccination plan moved forward, the federal government did not stop promoting the use of these drugs as a therapeutic measure, a message echoed by the most prominent evangelical leaders, reinforcing the informational disorder that helped Brazil become one of the main epicenters of the pandemic.”Moreover, questioning the vaccine’s effectiveness is linked to the discourse in favor of what is called the “early treatment,” (the “Covid kit” showed in the picture) that is, a set of drugs (such as Ivermectin and Hydroxychloroquine) that supposedly would help fight the virus, even though they have not proven effective. However, even as the national vaccination plan moved forward, the federal government did not stop promoting the use of these drugs as a therapeutic measure, a message echoed by the most prominent evangelical leaders, reinforcing the informational disorder that helped Brazil become one of the main epicenters of the pandemic.

Conclusion

Though the research period has ended, we continue to track the social media profiles of religious leaders, since it is a critical period for Brazil. In 2021, the Bolsonaro government was threatened by two factors: the aforementioned Parliamentary Inquiry Commission and opinion polls that indicate left-wing candidate Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT) would defeat Bolsonaro in the 2022 elections, including among evangelical voters.

In this scenario, the defense of the government’s positions, including the promotion of early treatment, has again circulated strongly in evangelical media. However, as we see in the image at the beginning of the essay, there is much more than the pandemic at stake, which highlights the importance of researching the discourses circulating in Brazilian religious media and on the social media of the most visible leaders,13A survey by Ideia Big Data/Avaaz showed that, in 2018, 85 percent of Bolsonaro voters had contact with pieces of disinformation that said that the candidate of the Workers’ Party, Fernando Haddad, had distributed a “gay kit” to schools when he was minister of education, and 56 percent of those who saw the story said they believed it. See AVAAZ, “Elections and Fake News” (presentation, October 2018). especially in election years such as 2022.

The defense of the Bolsonaro government is the defense of a neoconservative project14Flávia Biroli, Maria das Dores Campos Machado, Juan Marco Vaggione, “Introdução: Matrizes do neoconservadorismo religioso na América Latina,” in Gênero, neoconservadorismo e democracia (São Paulo: Boitempo, 2020), 13–40.—playing out in different countries in the Americas and Europe—in which actors from different sectors (conservative religious leaders, agribusiness, military sector) unite around agendas that center the defense of the patriarchal heteronormative family. In their defense of the family, they justify themes such as the criminalization of abortion, the defense of absolute freedom of expression, including speeches that can be characterized as homophobia, homeschooling, freeing up gun ownership, the hardening of public security actions, the end of the secular state via the justification of the existence of a “Christian nation,” and the diminishing of the state’s role in favor of neoliberal policies.

However, the discourse of conservative religious leaders and politicians do not correspond to an automatic adhesion of the evangelical electorate to the Bolsonarism project. Brazilian believers are much more politically heterogeneous than the conservatism of the most visible media and political leaders might indicate. As many researchers warn, there is no evangelical vote in Brazil. Multiple factors contribute to evangelical voters’ decisions.

Banner photo: Carolina Antunes for Palácio do Planalto/Flickr.