By late March 2020, reports began to surface of abandoned cadavers in the streets of the coastal Ecuadorian city of Guayaquil and, by April, the city’s residents reported waiting up to 17 days to bury loved ones. These reports and images were among the most traumatic for many of the people we interviewed. As one young man from the city of Ambato explained: “What impacted me most was in Guayaquil when there was the news of bodies scattered around that couldn’t be buried or cremated because the morgues were at capacity… It was a traumatic event that made me realize we were not prepared for this.”

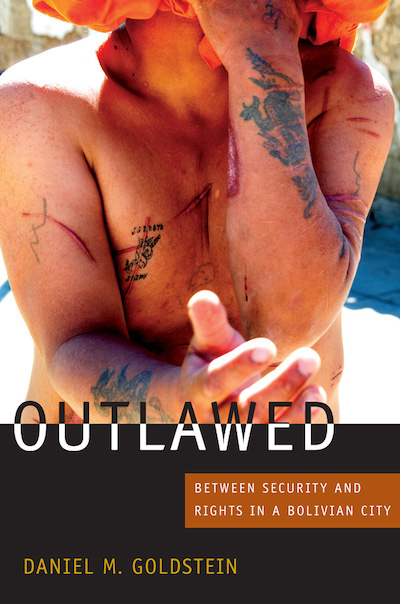

As medical professionals also began to realize the inadequacies of the country’s healthcare systems to face Covid-19, in large part due to insufficient state investment, then-President Lenin Moreno was focused on implementing a GPS-based system to track down Covid-positive patients who broke quarantine and sentence them with prison terms of one to three years along with fines. Behaving in what Daniel Goldstein has called the “phantom state”1 Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012More Info →—a state that is alternately present and even authoritarian in terms of security functions but absent in terms of social well-being—Moreno was swift in declaring a state of emergency, even as there were simultaneously widespread complaints that the government’s Covid-19 telephone hotline was unresponsive.

Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012More Info →—a state that is alternately present and even authoritarian in terms of security functions but absent in terms of social well-being—Moreno was swift in declaring a state of emergency, even as there were simultaneously widespread complaints that the government’s Covid-19 telephone hotline was unresponsive.

By May and June 2020, another failing of the state’s management of pandemic technologies was becoming apparent, as case after case of bribery, extortion, fraud, crony contracting, and trafficking in influence began to emerge regarding purchases of pandemic-related medical equipment by government health officials. In the most widely publicized case, hospital functionaries from Los Ceibos Hospital (part of Ecuador’s social security system) were charged with purchasing 4,000 body bags at 1,311 percent over market price in collusion with private contractors, including the son of ex-president Abdalá Bucaram. Other cases involved overpriced masks and emergency food kits, and, by the end of 2020, a total of 196 cases of corruption in pandemic contracting were under investigation.

Our research team sought to understand these failures and contradictions in government actions during the pandemic and how Ecuadorian people adapted in response. In our research, based on two sets of 40 and 32 qualitative interviews, respectively, conducted with participants that reflect the geographical and cultural diversity of the country, we sought to analyze the role of technology in Ecuador to understand how people experienced and perceived not only social solidarities but also social inequalities during the pandemic. While we focused on both communications and medical technologies, we understood pandemic technologies to broadly encompass any tool or system of knowledge utilized to respond, mitigate, or adapt to pandemic conditions or challenges, including alternative or local technologies such as forms of traditional, Indigenous, and ancestral medicine. Colonial histories of violence, as well as the modern Ecuadorian state’s nation-building projects, have reproduced structural inequalities along familiar lines of class, ethno-racial identity, and geographic region, where rural and Indigenous communities are more likely to be excluded and marginalized.2For example, see Mary Weismantel, Cholas and Pishtacos: Stories of Race and Sex in the Andes (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2001); see also Carmen Martínez Novo, Undoing Multiculturalism: Resource Extraction and Indigenous Rights in Ecuador (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2021). These very structural inequalities have been reproduced yet again by the Ecuadorian state in its management of communications and public health technologies during the pandemic. However, the very same marginalized communities or individuals generated their own adaptations and forms of agency in the face of an absent or negligent state, particularly in terms of education and healthcare.

Digital divides in education

While access to adequate devices and bandwidth for remote education was a widespread challenge, digital divides in education were particularly acute in rural and Indigenous communities, especially in the Amazonian region. Even for those who had internet access, the transition to remote learning was difficult for parents and guardians. As one mother we interviewed explained:

The mother has to be paying attention to this daughter, and the other daughter, and the signal gets interrupted, or some kid did something inappropriate and the class is suspended. And so, it’s more work for the parents who have to be sure if the child is comprehending, and the teacher doesn’t repeat things and just says that it’s recorded if we want.

However, such inconveniences were not even an option for much of the country’s population. At the national level, prepandemic census figures from 2019 indicated that only 45.5 percent of homes had internet access, while smartphone ownership stood at 46.0 percent nationally. In rural areas, these numbers are even more stark with home internet access dropping to 21.6 percent and smartphone ownership to 28.8 percent. As this data shows, inequalities in the country are framed by geographic and territorial dynamics, including urban/rural divides, as well as by the axes of class and ethno-racial identity. While poverty rates are certainly higher in rural zones and among Indigenous and Afro-Ecuadorian communities, and while longstanding racialized imaginaries associate Indigenous people with rurality, the economic reality today certainly also includes widespread urban poverty as well as urban Indigeneity.3For example, Luis Alberto Tuaza has estimated that as much as half of Ecuador’s Indigenous population now resides in urban and not rural zones. See Luis Alberto Tuaza, “Desarrollo, Identidad y Poder en las Comunidades Indígenas de Chimborazo (Ecuador),” Revista Andaluza de Antropología no. 17, (2019): 11–30. In addressing these contexts of inequality, even the education minister herself admitted during the transition to remote learning that at least 79,500 students had no internet access, and many of these students were left with only televised or radio-based lessons, at best. Many of the state’s solutions were criticized as inadequate by both our interviewees and in the international press.

When reporting on how people responded to the challenges of remote education, the national press tended to idealize and glorify individual instances of resilience. One example is the widely shared story of Carlos, a poor child who dutifully went to a bench in the public square where there was a wireless signal to attend virtual classes. However, our interviews suggest that collective agency and acts of local civil society collaboration and solidarity were the more common characteristics of responses to state failures in managing the technological inequalities related to remote education. For instance, in a rural, Afro-Ecuadorian community, an elderly gentleman we interviewed allowed neighbors to borrow his family’s computer and internet service regularly. Rural and Indigenous communities in the Amazon regions, where access to internet, cell phone service, and electricity can be scarce, implemented systems through which parents collected assignments and course content from the teacher’s house to deliver to their children. In other cases, multiple households collaborated to invest in purchasing and sharing a satellite-based internet service specializing in rural or remote regions. However, in responding to these conditions of technological marginalization in the context of the state’s focus on internet-based education, it was not lost on our interviewees that, even if resilient, they were filling in the gaps of the state’s inadequacies. As one interviewee expressed, given the state’s guarantee of free, universal basic education, it should also perhaps be responsible for covering the costs that families were now assuming with regard to technological devices and internet services. One young woman from the Galápagos Islands declared: “There’s no more money for food! It’s all going to the internet plan!”

State abandonment and medical pluralism

Along with education, the public health system was the other key place where our interviewees felt the state was neglectful and absent. Deficiencies in Ecuador’s healthcare systems are particularly acute in rural, Indigenous communities in both the Amazonian and highland regions. Indigenous interviewees consistently reported inadequate or nonexistent public health education or communication from the state, including the fact that information was not provided in Indigenous languages. In the case of the Waorani people, a provincial court even ruled that the Health and Social Inclusion Ministries had not provided them with sufficient communication, coordination, or pandemic relief. Given the mistrust of the public health system, based in part on its absence and lack of investment, many Indigenous migrants returned to their home communities, which attempted community quarantines through road closures or other forms of restricting access to communities. Without exception, our Indigenous interviewees reported that among their communities, there was significant mistrust and fear of hospitals as anonymous and impersonal places where people went to die or where they became sicker, whereas the home community was viewed as a healthier space in part due to the presence of personalized family and community support systems. Additionally, Indigenous interviewees recognized that adequate healthcare services, including testing, were not available for serious cases anyway in their regions. As a Shuar leader explained, people from his Amazonian community with respiratory problems had to travel two hours up to the mountain city of Loja to access adequate care.

The phenomenon of medical pluralism among Indigenous and rural populations, which involves the mixture of Indigenous, local, or ancestral medicine along with Western biomedicine, is common in the Andean region4 New York: Routledge, 2003More Info → and became one response to an absent state and negligent public health apparatus. Medical pluralism is a result of people’s knowledge of and experience with medicinal plants, and the pandemic activated Indigenous knowledge systems, health technologies, and health specialists, particularly around the use of plant-based teas and infusions. For example, in the Amazon region, herbs, roots, and different kinds of tree bark were often mentioned as ingredients in medicinal infusions that were already known to have anticoagulant properties and cure similar types of colds or flu. Interestingly, however, these remedies also sometimes included puro (highly concentrated alcohol) or Western medicines such as paracetamol. In other words, medical pluralism does not imply a binary separation pitting traditional against Western medicine but rather refers to the mixing and matching of diverse healing systems, in this case as one adaptive response to the inadequacy of public health systems in local Indigenous and rural contexts.

New York: Routledge, 2003More Info → and became one response to an absent state and negligent public health apparatus. Medical pluralism is a result of people’s knowledge of and experience with medicinal plants, and the pandemic activated Indigenous knowledge systems, health technologies, and health specialists, particularly around the use of plant-based teas and infusions. For example, in the Amazon region, herbs, roots, and different kinds of tree bark were often mentioned as ingredients in medicinal infusions that were already known to have anticoagulant properties and cure similar types of colds or flu. Interestingly, however, these remedies also sometimes included puro (highly concentrated alcohol) or Western medicines such as paracetamol. In other words, medical pluralism does not imply a binary separation pitting traditional against Western medicine but rather refers to the mixing and matching of diverse healing systems, in this case as one adaptive response to the inadequacy of public health systems in local Indigenous and rural contexts.

Curiously, Ecuador’s constitution defines the country as pluricultural and plurinational and recognizes rights regarding the inclusion of Indigenous and other intercultural healthcare practices in state-sponsored public health. The sort of intercultural, medical pluralism the state claims to aspire to is already occurring in the examples of everyday practice we have mentioned, but within official institutional spaces, this intercultural exchange has largely been limited to the posting of signs in hospitals and health departments in Kichwa or other Indigenous languages. The dominant system of medical knowledge and technology in the state’s public health apparatus continues to be overwhelmingly that of Western biomedicine. This lack of inclusion and recognition of non-Western healthcare is socially mirrored in the fact that the non-Indigenous, white/mestizo population often practices the use of plant-based teas and infusions as home remedies for various ailments but refers to these remedies colloquially as agüitas de vieja (old lady’s teas), failing to recognize the Indigenous roots of this health practice.

Conclusion: Intercultural health technologies and state denial

As we examine the constellation of inequalities, pandemic technologies, and the role of the state in Ecuador, we can appreciate how Ecuador’s most marginalized citizens in particular felt the state to be absent, inadequate, negligent, and even corrupt in its management of the lived consequences of the pandemic. This perception was linked particularly to state failures in terms of facilitating transitions to internet-based education and in guaranteeing meaningful and inclusive access to public health systems. Without glorifying their resilience as the solution to state failures, we have tried to show the forms of agency nevertheless exercised by civil society actors and everyday citizens in Ecuador to adapt, innovate, and fill in the gaps left by the state. However, our results also show the ongoing need to address Ecuador’s historic social inequalities in order to increase equity of access to medical and communications technologies and to foster greater dialogue and intercultural practices of medical pluralism in an already avowedly, pluricultural state.

Banner image: A caretaker disinfects a cemetery in the Calderón district of Quito. Photo by Juan Diego Montenegro.