The UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs has noted that “the coronavirus pandemic poses a grave health threat to Indigenous peoples around the world.” The threat has proven not only epidemiological, but also social and economic as many countries imposed strict lockdowns that created additional burdens on communities already suffering from resource deprivation and marginalization. In India, indigenous communities—legally known as “Scheduled Tribes” or popularly termed “Adivasi” (“original inhabitant”)—are highly dependent on performing migrant labor for subsistence. Several preliminary studies have shown that these populations were highly vulnerable during India’s harsh lockdown, which lasted from March to May 2020 in order to combat the first wave of Covid-19.1→Minaketan Behera and Preksha Dassani, “Livelihood Vulnerabilities of Tribals during COVID-19, Challenges and Policy Measures,” Economic & Political Weekly 61, no. 11 (2021): 19–22.

→Vatya Raina and Ananya, “The Lockdown in India: Understanding the Matrix of Caste, Class and Gender,” Economic & Political Weekly 61, no. 8 (2021): 12–16.

→Aashish Xaxa, “Minor Forest Produce and Tribal Livelihood in the era of COVID–19” in India’s Indigenous Peoples: A Journey on Self–Reflection on Society, Culture and Sustainability, eds. Virginius Xaxa and Vincent Ekka (New Delhi: Indian Social Institute, 2021), 284–296. There also have been academic and journalistic accounts of the “great migration” caused by the lockdown in which, conservative estimates suggest, over 15 million people returned to their home villages from cities and industrial centers during this period, many suffering intense hardships along the way.2Indrajit Roy et al., “Precarious Transitions: Mobility and Citizenship in a Rising Power,” Economic & Political Weekly: Engage, February 8, 2021. However, there has been very little ethnographic engagement with the effects of the lockdown on the villages where the migrants returned during the lockdown.

This study examines two villages in indigenous (“Schedule 5”) regions in western and eastern India, where a significant part of the population is involved in migrant labor. The villages were chosen due to their different migration profiles. In western India, most people migrated for work within the region, whereas in the east they typically migrated long distances, primarily to the west, for work. We found that in villages in both regions, the differential access to agricultural and forest land shaped experiences of the lockdown among return migrants and their families. However, in the east the added experience of long-distance migration led to more demands from the state while in the west, where people were left on their own, they quickly returned to work to secure their livelihoods.

Indigeneity, migrant labor, and the pandemic

While the government of India does not officially acknowledge any particular group as “indigenous,” the Constitution of India empowers the state to list certain communities as “Scheduled Tribes” based on “geographic isolation,” “primitive” characteristics and “distinctive culture.”3→ Constitution of India, Art. 342.

→National Commission of Scheduled Tribes Report (2003), 1. These dated and colonial criteria of classification, in addition to longstanding claims on the part of the tribal communities to land, have led many scholars to make parallels between these communities and indigenous peoples in settler colonial contexts and elsewhere.4For more on the debate, see Bengt Karlsson and T.B. Subba, Indigeneity in India (Routledge, 2016).

In addition to empowering the state to list communities as “Scheduled Tribe,” the Constitution also defines certain areas that have high concentration of these communities as “Scheduled Areas” under the 5th Schedule. This allows a degree of autonomy in governance and targeted development initiatives in these regions, which are some of the poorest in the country. While Schedule 5 areas are comprised predominately of Scheduled Tribe communities, as our study shows, they also have substantial populations of other marginalized groups including Scheduled Castes (also called “Dalit,” or formerly known as “Untouchable”), and Other Backward Classes, which include artisan and pastoral communities. All of these communities are subject to various affirmative action programs by the state.

Despite the guarantees of development, Schedule 5 areas remain some of the poorest regions in the country with limited access to schools, hospitals, roads, and gainful employment. Additionally, these areas also are located in the forests and hills where agriculture is not enough for subsistence. As a result, seasonal migration to industrial centers or fertile agricultural regions is common.

The study focused on two Schedule 5 villages, Moti Sadli in the western Indian state of Gujarat, and Bharbaria in the eastern Indian state of Jharkhand. Our aim was to analytically assess from an ethnographic perspective the experience of migrant workers and their families, as well as the social, political, and economic conditions of the villages following the lockdown. The regions in which the villages are located have different profiles within the larger circuit of migration in India: Gujarat, which is a highly industrialized state, is seen as a “receiver” region, attracting labor migration from all over the country; Jharkhand is considered a “sender” region from which labor migrates, typically west or south.5Rameez Abbas and Divya Varma, “Internal Labor Migration in India Raises Challenge for Migrants,” Online Journal of the Migration Policy Institute, March 3, 2014. However, both states are part of Schedule 5 with 14 and 21 percent indigenous (ST) populations, respectively. The difference is that from Schedule 5 regions in Gujarat, most migrate within the state, while in Jharkhand, most migrate to other states, such as Gujarat, for work.

Same village, different experiences

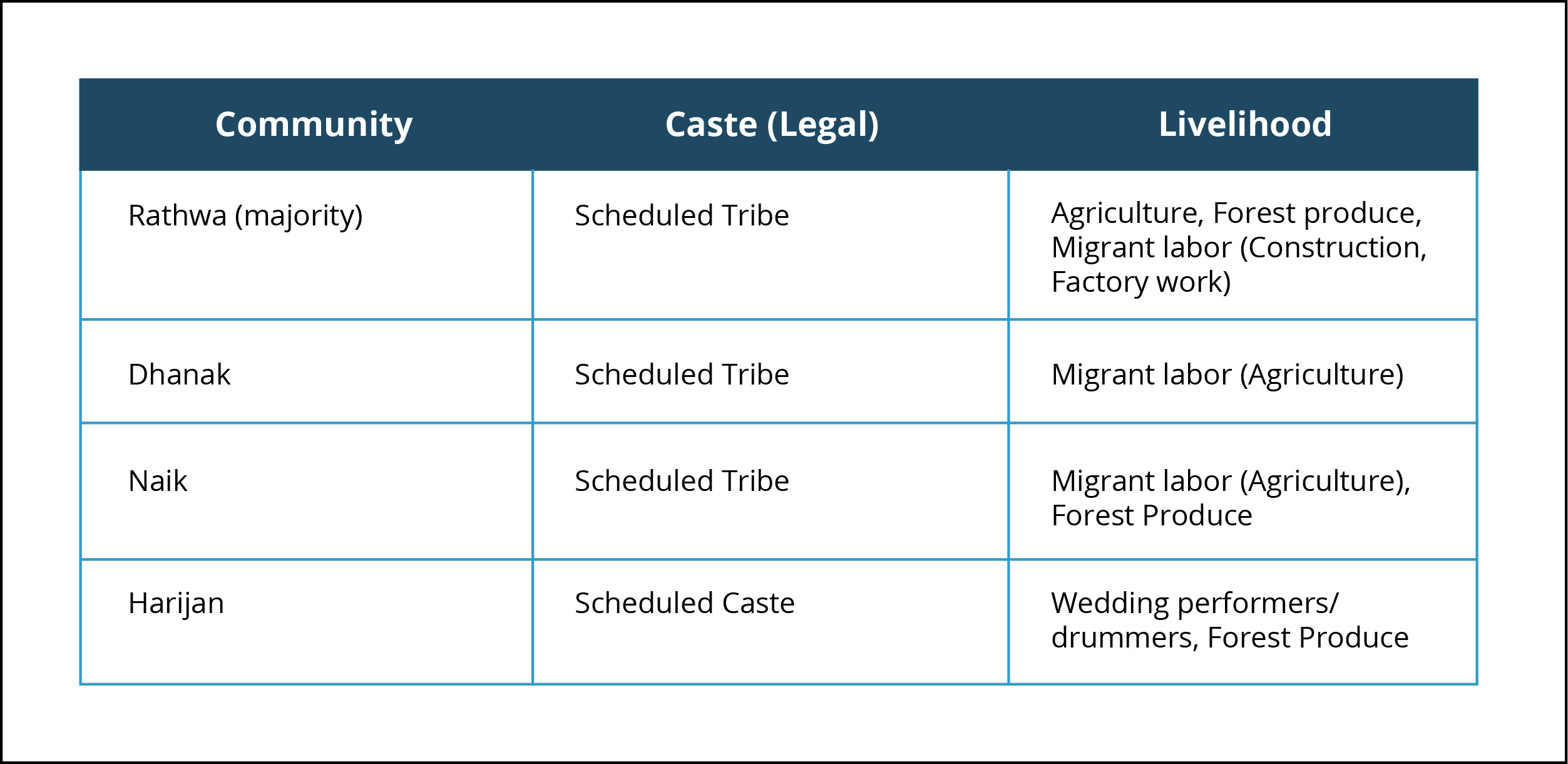

Despite popular ideas that imagine indigenous villages in Schedule 5 areas as homogenous, they are comprised of different communities that have unequal access to resources. In Moti Sadli village in Gujarat, with a population of 3,279,6Census of India, Moti Sadli village, 2011. there are four major communities:

The Rathwa is the largest tribe in the village and practice subsistence agriculture and have rights to forest land. They are also relatively more educated than the other communities. Besides agriculture, some Rathwas travel to the cities of central and southern Gujarat (such as Ahmedabad, Vadodara, and Surat) mainly in search of construction work. Dhanaks and Naiks are indigenous groups that have no land, although the latter have some claims to the forest. These communities are less educated, and they often go to the fertile areas of western Gujarat to work as farm labor, where much of their salary is paid in kind from the season’s crop. The Harijan community are a Schedule Caste group who have settled in the village. Their main source of income comes from performing music at the weddings of indigenous communities and also from making and selling baskets and other items from collected forest materials such as bamboo. Their education level is comparatively lower.

The effects of the lockdown in Moti Sadli were distributed across the communities of the village in different ways. Many Rathwas who worked in the cities of Gujarat, which were most affected in the early wave of the pandemic, returned to the village. Several migrant laborers used this time to remodel their village homes. As the agricultural season had ended, there was some food available, although since markets were closed, surplus agriculture could not be converted to cash. As Rathwas had access to the forest, the community could also gather the flowers of the mahua tree (which was in blooming season), which is sold either raw or is distilled and sold as a beverage.

The other communities who did not have land had different experiences of the lockdown. Members of the Harijan community did not migrate for labor; their loss of livelihood came primarily from the shutting down of weekly markets (hat) where they sell their goods and the cancellation of weddings. They attempted to compensate for this by setting up exchanges in the local villages instead of market towns to circumvent lockdown restrictions. Members of the Naik and Dhanak communities are also landless but depend on migrant farm labor for their livelihoods. As a result, many did not return during the lockdown, instead choosing to stay in the fields where they worked and survive off their portion of the season’s harvest. Some, however, did return and their stories were more harrowing. For example, one Dhanak man recounted his family’s journey from western Gujarat, and how after they returned to the village, they had no more food left. He and his family traded seeds, which they had collected from their work sites, with merchants for food grains, and then managed to pool together enough food grains from community members and neighbors to stave off starvation.

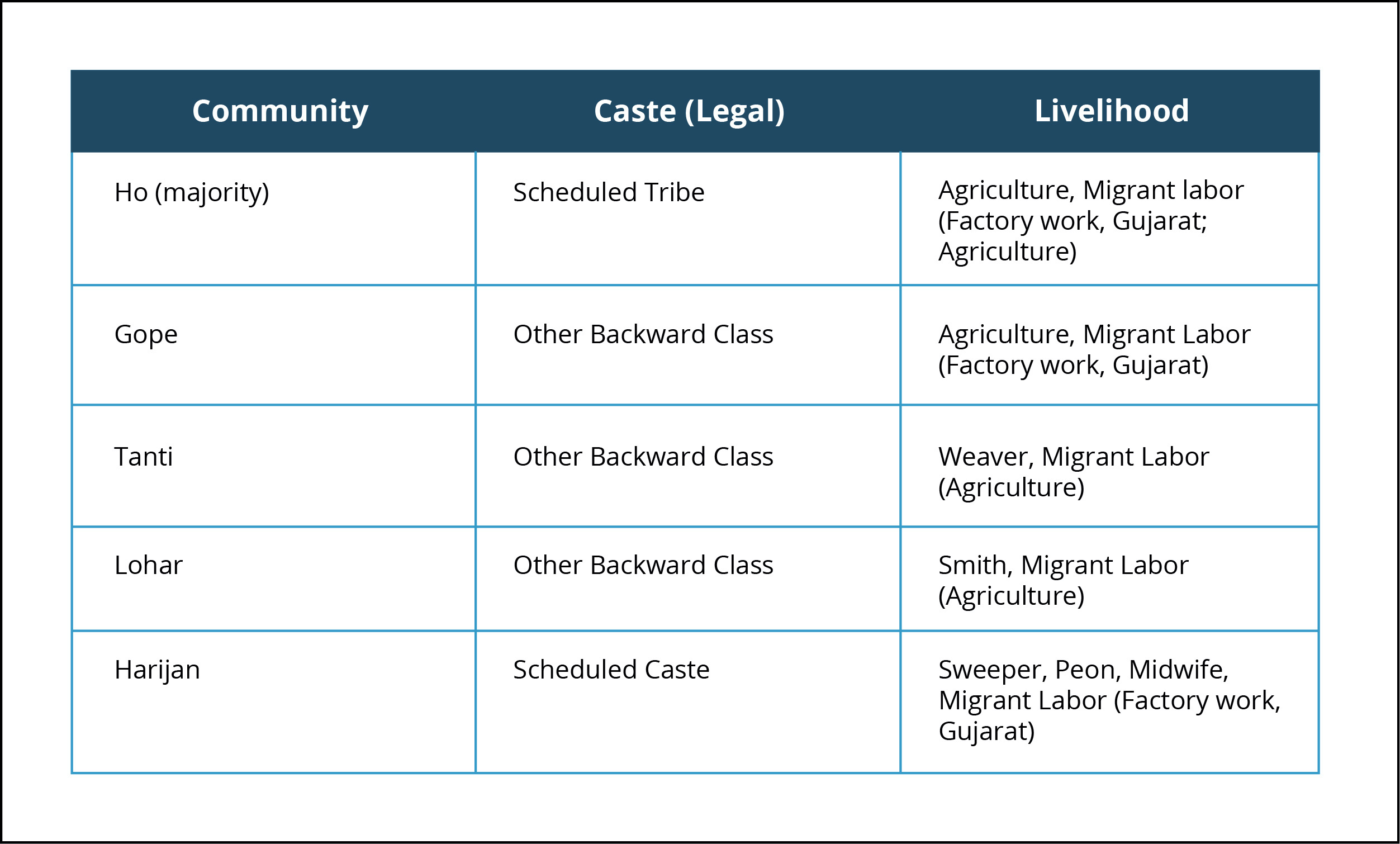

In Bharbharia village, Jharkhand, which is a Schedule 5 area in West Singhbhum district, there is also community-wise differentiation of land ownership. Bharbharia has a population of 2,966,7Census of India, Bharbharia village, 2011. with five major communities:

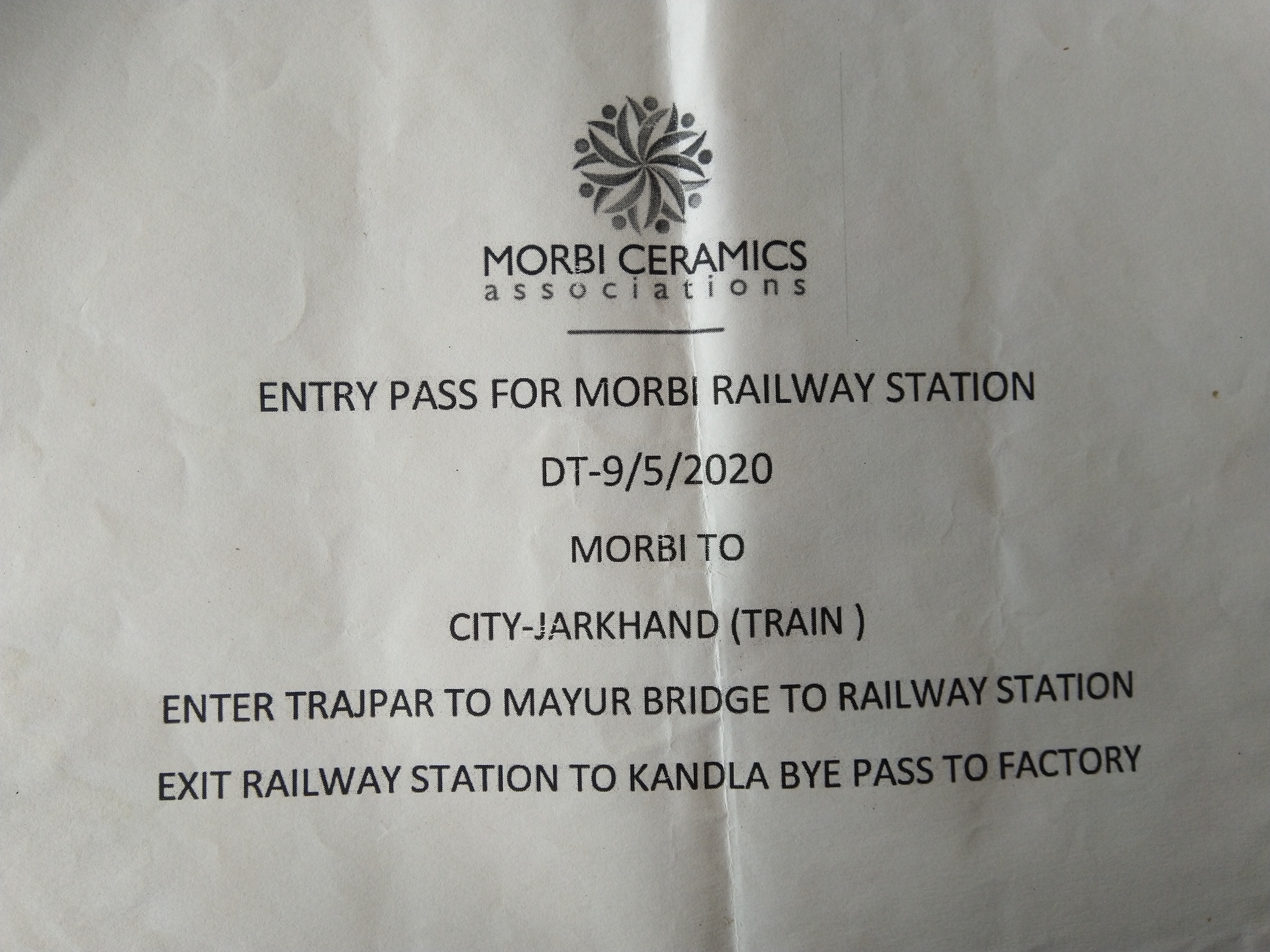

The Ho community, which is the majority group in the area, have small landholdings and practice subsistence agriculture, and the Gope (cowherd caste) also have land. The Lohar, Tanti, and Harijan do not have any landholdings. Like in Moti Sadli, because of the paucity of landholdings, lack of irrigation, etc., most households in the village are dependent on income from migrant labor. However, instead of migrating within their own region, many of the male members across communities migrate almost 2,000 kilometers to Gujarat to work in factories. The lockdown entailed a different experience for many of them as the return journeys were quite arduous. Some factory owners were kind enough to cover expenses and provide food and accommodation to out-of-state laborers until the Indian government started limited train services to transport them back to their villages. Having finally returned, the Jharkhand government processed them, and according to many, performed Covid tests (however, some said these were simply temperature checks) at the nearest train station. They then had to find their ways home through hired transport, special buses, or by walking.

Interviews were mainly conducted with the landowning Ho tribal community and the landless Harijan community, since they formed the majority in the village and were found in larger numbers at home during the period of research. Like in Moti Sadli, the end of the agricultural season meant that for those who had land, there was some agricultural produce available for subsistence. However, the closure of markets prohibited the sale of excess produce, so cash was not available for essential items like cooking oil, soap, detergent, etc. Throughout the lockdown some rations were made available through central and state government schemes of rice and lentils, but people complained that these were of low quality. Also, like in Moti Sadli, many of the migrant Ho workers used this time to remodel and repair their family homes. Some others brought with them goods from Gujarat and set up small shops in the villages. Yet, other households survived on income from selling rice beer (handiya).

Landless Harijan (SC) households in Bharbharia are also dependent on migrant labor, with many of the men migrating to Gujarat for work. However, unlike the Ho, where women were mainly engaged in agricultural activities, Harijan women worked as sweepers in the local hospital located in a nearby town, generating dual incomes. There was also an emphasis on education with many in the household studying and aiming for college degrees as a way to improve their financial and social circumstances. The lockdown, however, stopped both these dual streams of income, since migrant laborers returned home, and the government hospital abruptly dismissed many of the women from their sweeper positions. The lockdown also interrupted the studies of those from the community who were pursuing higher education. This put households in difficult financial circumstances and made them especially dependent on state support. This is also perhaps why Harijan households had more expectations than tribal households from the Jharkhand government, which during the lockdown had undertaken a skill survey in the state with the promise of creating local job opportunities. However, after long delays in the implementation of such initiatives, many, especially women, were eager for male community members to return to Gujarat to contribute financially. Meanwhile, women sustained the household by selling rice beer.

Overall, the study showed that in both Gujarat and Jharkhand the communities had a difficult time economically supporting the return of migrants during the lockdown. Agricultural stocks quickly dwindled and support from the government was scant and poorly implemented. Although the Jharkhand government (being a “sender” region) expressed greater intention to support the return of laborers, leading some not to return to work, most still expressed the desire to return as soon as possible.

Conclusion

The impact of the lockdown was manifold in the 5th Schedule villages of Gujarat and Jharkhand. In both cases, migrant workers had a difficult time returning home, and endured several hardships along the way. Once home, the social position of a particular community greatly conditioned the experience and possibility of self-sufficiency under the stringent lockdown conditions. The dominant indigenous communities, such as the Ho and Rathwa, due to their access to land and natural resources could more easily weather the pandemic lockdown, while the landless indigenous communities and the formerly untouchable communities had to improvise in order to survive. Due to the closure of weekly markets, the communities emphasized localized forms of trade and a greater sense of dependence on the village community.

However, these strategies had their limits and could only provide sustenance for a limited period. As soon as lockdown conditions were lifted, there was a significant outflow of migrant labor back to their previous places of employment, contrary to reports from other parts of the country suggesting that migrants were more likely to stay in the villages. One major difference in the study sites was the expectation of people from the local governments. In Gujarat, people had very little expectation that the government would provide alternative livelihoods for greater self-sufficiency, while in Jharkhand, there were some overtures made by the state government to promote local employment. However, according to the consultants most of these initiatives failed to yield results.

The findings revealed that indigenous communities could survive when cut off from the market economy; however, the conditions of survival differed due to unequal access to resources. It also showed that despite the special status of these areas, state development activities have been insufficient to curtail migration brought about by countervailing policies of resource extraction and agricultural degradation. We suggest that policies emphasizing local employment and skills generation such as that envisioned by the Jharkhand government be properly implemented across all Schedule 5 areas of the country. In addition, policies also need to emphasize that all communities residing in these areas have access to sustenance and income either through agriculture or forest rights. Such policies could mitigate the overall survival burden during future crises.

Banner photo: Selling herbal medicines in the weekly market, Chhota Udepur, Gujarat. Photo by Kalpesh Rathwa.

References:

→Vatya Raina and Ananya, “The Lockdown in India: Understanding the Matrix of Caste, Class and Gender,” Economic & Political Weekly 61, no. 8 (2021): 12–16.

→Aashish Xaxa, “Minor Forest Produce and Tribal Livelihood in the era of COVID–19” in India’s Indigenous Peoples: A Journey on Self–Reflection on Society, Culture and Sustainability, eds. Virginius Xaxa and Vincent Ekka (New Delhi: Indian Social Institute, 2021), 284–296.