Covid-19 disproportionately affects disabled, chronically ill, and elderly people across the globe. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control state that those with chronic illnesses or disabilities, as well as those over the age of 65, are in the highest risk categories for Covid-19. While there are physiological reasons for the particularly deadly effects of the virus on disabled and elderly folks once they’re exposed, the disproportionate spread of Covid-19 and risk of infection in these populations result from social conditions. For example, many individuals occupying these categories in the United States live in nursing homes and other congregant care facilities where they cannot isolate. Residents and workers of such facilities accounted for nearly one-third of Covid-19 deaths in the United States at one point in 2020, as well as accounted for more than 40 percent of all Covid-19 deaths. Efforts to address the injustices associated with institutionalizing disabled people in the United States have been of central importance in disability advocacy and scholarship. But according to the Congressional Budget Office, the vast majority of chronically ill and disabled people—80 percent of them—live in private homes in the community. The effects of the pandemic on them and their caregivers are also profound and socially manufactured. However, they are far more dispersed, their interactions with health and home care institutions are individualized, and their experiences are hidden in the intimacy of their homes.

Rendering invisible lives visible

To better understand the distal effects of the pandemic on such households, this research solicited stories from family members, specifically spouses or partners, caring for a disabled partner at home. According to the AARP, there are 53 million family caregivers across the United States, with an increase of nearly 10 million in just the last five years. This invisible “front line” is an essential part of the US healthcare system; their unpaid labor prevents a further explosion of long-term care costs in the United States. According to the Scan Foundation, unpaid caregiving is worth more than $470 billion dollars, which is more than all other long-term care markets combined. The United States relies on unpaid family caregivers partly because it is the only industrialized nation in the world that does not offer universal healthcare and because it has little in the way of publicly funded home care supports compared to other countries. The lack of robust funding for home and community-based support in the United States—or what many are now discussing as care infrastructure—is an issue disability advocates and scholars have long sounded alarms about. And the problems stemming from a lack of care infrastructure are not going away. The US Census Bureau notes that current demographic changes mean that the number of older and disabled adults is rapidly increasing. Moreover, technological change has resulted in people living longer with more complex conditions. These changes, combined with the lack of care infrastructure in the United States, result in the responsibilities of care being offloaded to families, and often times this care is highly medically complex.

Although studies track data on Covid-19 in long-term care facilities, we know little about the invisible lives of unpaid family caregivers and those they’re caring for at home. What we do know is that, due to Covid-19, this care work is now happening under further duress. A 2020 survey by AARP of family caregivers showed that the pandemic caused a significant increase in worry, stress, and anxiety. In another survey, 83 percent of caregivers reported more stress during Covid. My research focused on understanding one particular subtype of family caregiver: spousal caregivers. Pre-pandemic, the lives of spousal caregivers were already known to differ from other types of family caregivers in meaningful ways: They assist with more activities of daily living, perform more medical or nursing tasks, are almost always the sole caregiver, and are far more likely to be doing “high intensity” caregiving. They also report feeling significantly more stressed and more alone than other types of family caregivers.

How did the pandemic affect the lives of spousal caregivers and what do their stories tell us? To find out, I recruited spousal caregivers through online caregiver support forums on Facebook and through local support groups. I interviewed 44 caregivers across 21 states ranging in age from 29–87. Reflective of prior research showing that white people utilize formal caregiving supports more than other racial or ethnic groups,1The literature on formal versus informal caregiving support utilization largely indicates that people of color tend to rely on churches and/or other informal community networks, while white people tend to use formal supports like organizations explicitly geared toward caregivers. For further reading, please see Julian Chun-Chung Chow et al., “Types and Sources of Support Received by Family Caregivers of Older Adults from Diverse Racial and Ethnic Groups,” Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work 19, no. 3 (2010): 175–194. my participants were primarily white and they occupied a range of socioeconomic statuses.2I interviewed nearly all of the participants at least twice either on the phone or over a video call. The average length of time I spent talking to each participant in total was more than two hours, with a range of 1.5 hours to 5 hours.

Increased care demands on already overstretched caregivers

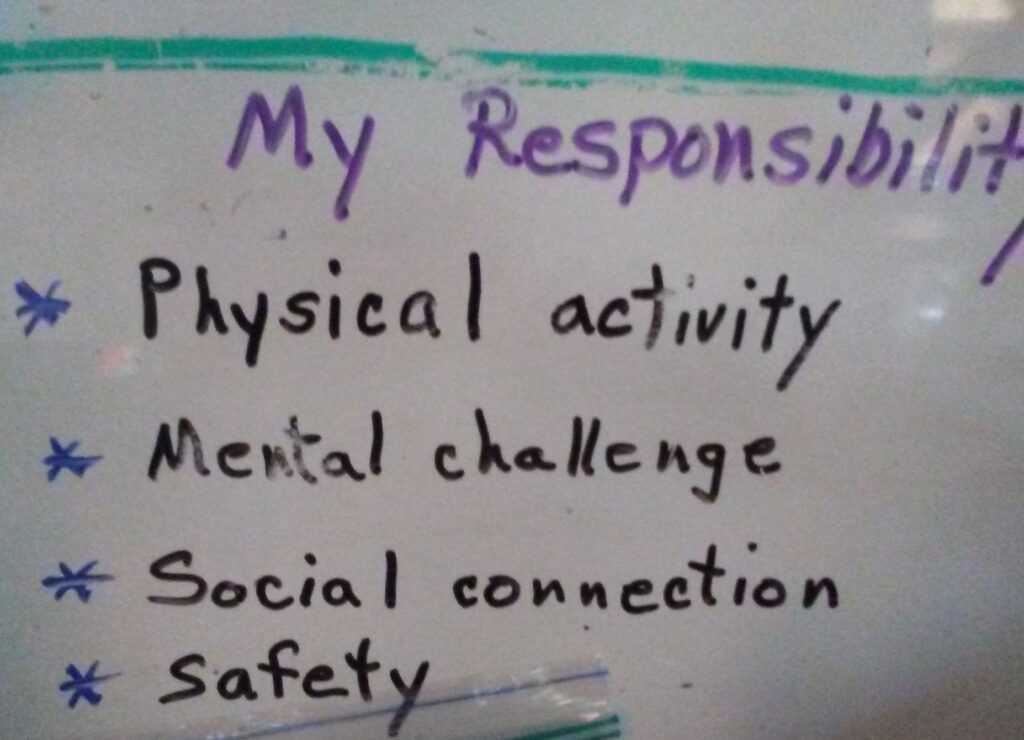

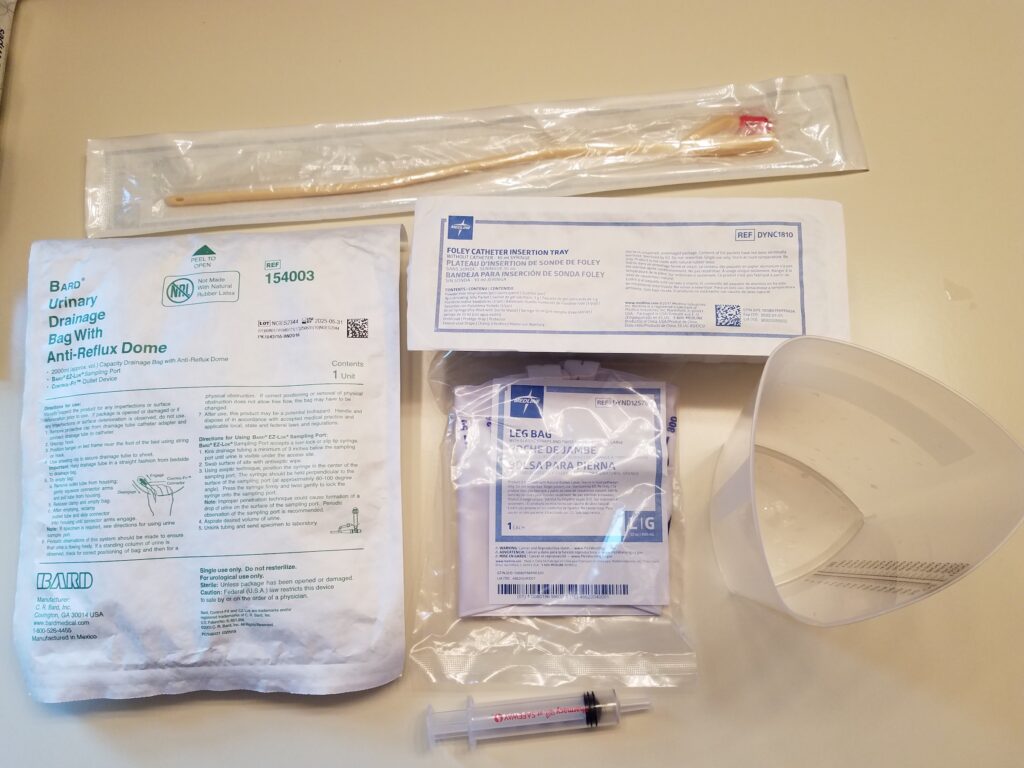

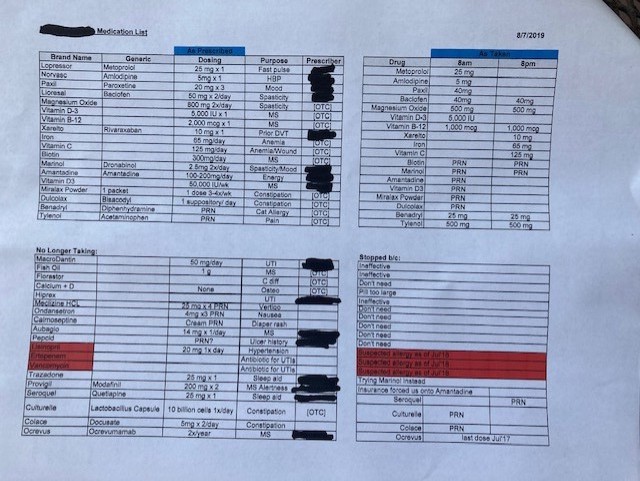

As I reported elsewhere, spousal caregivers deliver complex care, but the pandemic increased the complexity and amount of care they provided. People are now sent home with more complex technologies that require an array of skills to manage. In interviews, caregivers mastered simple blood pressure machines, glucose monitoring devices and insulin shots, to more complicated technologies like feeding tubes and infusion equipment with tubing and computerized infusion pumps. They change foley, condom, or suprapubic catheters; they run and maintain CPAP machines, suction machines for removing excess mucus, nebulizers, power wheelchairs, and hospital beds. They perform intensive wound care. In the wake of Covid-19, however, seeing healthcare providers in medical settings when things escalated at home—such as when a fall occurs, wounds become infected, and so on—became too risky. Instead of taking their spouse to a hospital for care, they would get on the phone or be instructed via telehealth on how to care for their spouse, monitor them, dose them with meds, and so on at home where they were safer because of the risk of Covid-19 in healthcare settings.

For many caregivers, these pressures resulted in more extreme and entrenched anxiety and stress. One woman described in grisly detail cleaning stubborn wounds on her husband’s feet in which his tendons were exposed. Due to his rare inflammatory skin disease, these have been recurring for years. Though they were carefully cleaned for weeks and sometimes months, the wounds had repeatedly landed him in the emergency room in the past. But the pandemic has made such wound care all the more challenging, since going to the hospital became too dangerous. “The new plan is…elevate the foot, give him Gatorade, and dose him with 60 to 80 milligrams of prednisone. So, I’m the new ER doc now….What pressure on a caregiver! With a fever of 101 it might be fluid in his foot, but it could also be some other kind of infection that will kill him.”

Shared isolation: “Now everyone else sees what it’s like”

Some participants said that their lives did not change much when the pandemic hit. For many of my participants, like others in the disability community, there were already structural and attitudinal barriers toward disability resulting in isolation. For example, they could not go out with their disabled partner without an accessible vehicle (something that costs tens of thousands of dollars) and public transportation—which was often already inaccessible—was not an option during the pandemic. For some, their spouse needed a level of attention and care that they could not provide alone. If their spouse had dementia, they may not understand why a mask was needed or be able to easily adapt to new routines for going out. That is, without support in the form of a home health aide or personal care attendant (which often requires paying out of pocket), they were not able to leave their house anyway. Participants also reported that friends and family did not understand their partner’s illness, weren’t willing to accommodate their spouse’s needs, or did not make them feel welcome. In this sense, they felt like the pandemic was certainly terrible, but also that everyone else was now joining them in experiencing social isolation.

Simultaneously, many participants felt like the pandemic made their lives better when it came to being able to attend work or events virtually, something many in disability communities point out they had long been requesting. Many of the participants in this study indeed had been isolated for years due to their care responsibilities for their spouses, but suddenly, everything shifted online, and it opened up new worlds not just for their disabled partners but for themselves. They could now do things on their own or with their partners such as attend talks, go to church, listen to a symphony, or have video calls with friends and family at a far greater frequency. The normalization of shifting events and social meetings online was a net positive for some caregivers and their disabled spouses. One of the biggest losses of emotional support for participants was the loss of their local support groups. Some caregiver support organizations shifted to online meetings and this was a lifeline for many. As we begin to emerge from the pandemic, participants in this study, like many disabled folks, are concerned about the potential loss of virtual options.

The intersection of precarious homecare workers and family caregiving

Many participants discussed how badly the pandemic hit them because what had once been a fragilely stitched together system of care abruptly fell apart. Because we as a society devalue disabled people, we devalue those that care for them. This is evidenced by home care in the United States being notoriously low wage, with much of the problem being rooted in labor regulations that allow low wages for home care, which is work predominantly performed by women of color. Participants explained to me how their aides are paid so poorly by agencies that they often have to work multiple jobs with multiple agencies/households to make ends meet. This meant their aide might be in other houses as well and this cemented their decision that it was no longer safe to risk exposure or contamination by continuing to have their home health aide work. As a result, many were too afraid to continue utilizing them. Caregivers who previously had aides now had none and suddenly spouses were providing 24-hour care, including hospice care, and some were unable to hardly sleep or eat or take care of themselves. Many were fraying, and quickly, sobbing on video calls. Anxiety overtook them; many talked about how afraid they were to slip up. If they had to go out and get groceries or obtain medical supplies, they were terrified of bringing home the virus. As I wrote elsewhere, one caregiver summed up this fear of their partner dying by telling me “If he gets Covid, it’s over.” The profound responsibility for their partner’s well-being, lack of support, and fear of slipping up resulted in caregivers being asked to do more with less help and trying to manage unrelenting anxiety.

A future of valuing care?

The pandemic has certainly brought issues of caregiving and the need for a stronger care infrastructure in the United States front and center in public discourse. But whether or not this translates into greater recognition of unpaid family or spousal caregiving through increased resource allocation, prioritization of home and community-based services, and long-term support services to relieve caregivers and enhance the lives of disabled people remains to be seen. At present, advocates for those who are aging, disabled, and/or chronically ill are all agitating for greater attention to caregiving and care infrastructure. A broad coalition of stakeholders supported the Biden administration’s Build Back Better bill. This plan includes addressing critical care infrastructure needs like better pay for home care workers, reducing wait lists for home and community-based services, and expanding eligibility for long term support services.

The bill is currently stalled while disabled people, their caregivers, and paid home care workers continue to live in untenable circumstances. Many in disability justice communities are turning to mutual aid and care collectives. But as the pandemic recedes, the need for care will not end. Will the conversations about strengthening our care infrastructure occurring in the wake of the pandemic translate into the United States correcting its lack of support for care? As the future unfolds, organizations that support spousal caregivers, such as the Well Spouse Association, advocate for a range of programs that would ease the pressures on caregivers. These include single-payer healthcare to expand access and improve overall health, expanding access to publicly funded long-term care programs, and expanding Medicaid eligibility. Medicaid is the country’s only publicly funded source of home and community-based long-term care. However, it is notoriously difficult to qualify for and is run differently in all 50 states.3 Russell Sage Foundation, 2018More Info → But these caregivers’ stories show that it is past time to re-examine resource allocation regarding care. As rates of disability increase, relying on spouses as the care infrastructure for adults in the United States is not sustainable.

Russell Sage Foundation, 2018More Info → But these caregivers’ stories show that it is past time to re-examine resource allocation regarding care. As rates of disability increase, relying on spouses as the care infrastructure for adults in the United States is not sustainable.

All images in this essay were taken by participants in the study.