In the earliest weeks of the Covid-19 pandemic, there was a significant shift in how companies responded to the uncertainty and new restrictions that accompanied increasing concerns about the virus. While some industries began laying off workers, others shifted to remote work. Pew Research surveyed US workers in October 2020, finding that about 40 percent said their job could be done remotely, although there was significant variance across industries. According to Pew, workers in finance, technology, and education sectors were the most likely to say their work could be remote, while retail, manufacturing, and hospitality workers were the least likely.

Unsurprisingly, employers wanted assurances that productivity would continue while workers were not directly under a manager’s eye. For example, a New York Times article described how new monitoring software promised to provide granular tracking of employees and generate productivity scores based on every click and keystroke employees made while logged in from home. In the earliest months of the pandemic, companies were already thinking of new ways to track employees’ location, proximity to other coworkers, and measures of physical health for when they eventually returned to the office.

“Just over a century ago, Henry Ford had a team of more than 200 investigators monitoring employees and visiting their homes to ensure they were model citizens and workers.”Workplace monitoring is not new; employers have been seeking ways to better track employees for decades. Just over a century ago, Henry Ford had a team of more than 200 investigators monitoring employees and visiting their homes to ensure they were model citizens and workers. Today, workplace wellness programs provide access to wearables like Fitbits to track employees’ health—and even their job performance.1For a review of workplace wellness programs, see Soeren Mattke et al., Workplace Wellness Programs: Services Offered, Participation, and Incentives (RAND Corporation, 2015), 7. In some workplaces, employees may have to pay financial penalties if they don’t meet certain health and wellness metrics, or if they refuse to participate in a wellness program.

Beyond this interest in monitoring employee wellness, the last decade has seen a steady increase in workplace surveillance more broadly. A 2019 study of 239 large corporations found that 50 percent were using “nontraditional” surveillance methods, including logging and analyzing phone calls, scrutinizing emails and social media posts, and tracking who attends meetings, an increase from only 30 percent four years earlier. The Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated these concerns, as the shift to remote work has led to a wide range of new ways that employers can track their employees’ movements, behaviors, and general productivity.

The intensification in workplace surveillance amid changing work environments raises important questions about the exercise of power and employees’ privacy rights. With support from the Social Science Research Council’s Covid-19 Rapid Response grant program, our research provides insight into how surveillance technologies are being deployed in different industries, employees’ awareness of these practices, and specific concerns workers have about different forms of surveillance. What are the negative impacts of surveillance on workers’ privacy, human rights, and empowerment?2For an overview, see Kristie Ball, “Workplace Surveillance: An Overview,” Labor History 51, no. 1 (2010): 87–106. Below, we share results from a survey of US remote workers we conducted in fall 2020 and consider the implications of this research for employees returning to the office. Though not fully representational of the workforce, our respondents revealed surprising information, among them concerns over health data use for reducing healthcare costs and worries over who will have access to any data gathered by employers.

Work experiences during the pandemic

To understand how the pandemic affected work surveillance practices in US companies and how workers felt about potential increases in surveillance practices, we surveyed 645 American adults who had been working at the same company since at least the start of 2020 and who had been able to work remotely for at least part of the pandemic. Our respondents were 53 percent male, 84 percent white, and the average age was 44. Most (77 percent) had at least a bachelor’s degree, and the most common industries represented were Information Technology (23 percent), Business/Finance (15 percent), and Education (14 percent).

Over the course of the pandemic, workers reported significant increases in job stress and decreases in job satisfaction and job security. Given high unemployment rates and additional pandemic-related stressors, these findings align with what other researchers have found,3Jenna M. Wilson et al., “Job Insecurity and Financial Concern during the Covid-19 Pandemic Are Associated with Worse Mental Health,” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 62, no. 9 (2020): 686–691. but also point to concerns over possible changes in workplace monitoring during the pandemic.

“More concerning, when asked whether their employer had begun using new technologies or changed workplace monitoring policies, 23 percent said they weren’t sure, suggesting confusion about what policies may have changed due to the pandemic.”Our data shows that overall, workplace monitoring was quite common before the pandemic: 78 percent of respondents said their company used at least one form of monitoring from a list of 12 options. Monitoring time and attendance (61.4 percent), work email (40.5 percent), physical location (32.9 percent), and network access (28.9 percent) were the most common forms of monitoring reported. Just 12.9 percent said their employer did not monitor them. More concerning, when asked whether their employer had begun using new technologies or changed workplace monitoring policies, 23 percent said they weren’t sure, suggesting confusion about what policies may have changed due to the pandemic. Among those who said their employer had not instituted new forms of monitoring since the start of the pandemic, nearly half (46 percent) said they were concerned there would be increases in a post-Covid workspace.

Concerns about future monitoring

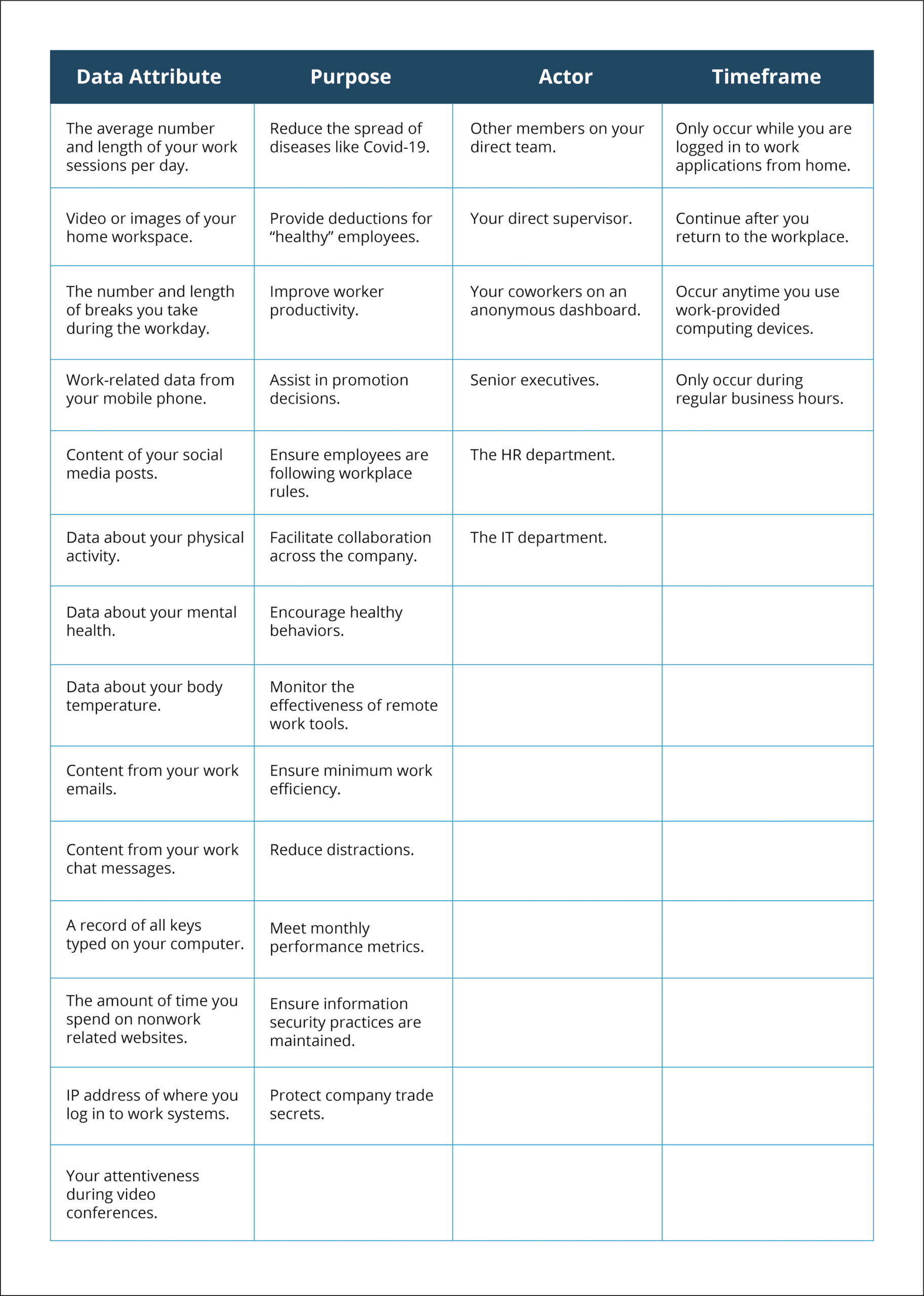

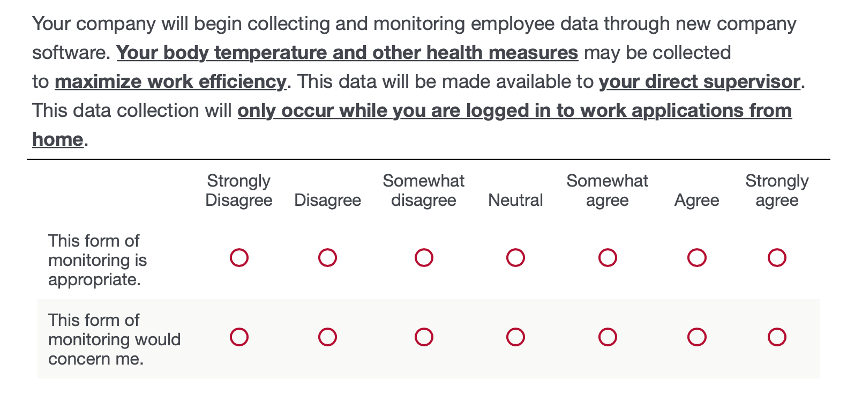

Our research also explored workers’ comfort and concern regarding different types of surveillance. Each respondent viewed 35 scenarios, each following the same structure regarding a new surveillance program at work, but randomly varying (1) the type of data collected, (2) the stated purpose of the data collection, (3) the actors the data would be shared with, and (4) timeframes during which the data will be collected (see Figs. 1 and 2 below for a sample vignette from the survey and a list of the items included for each factor). For each scenario, the respondent was asked to rate how appropriate they felt the monitoring program was and how concerned they were about the program. In total, we collected participant responses to more than 20,000 vignettes across our 650 participants. These ratings allowed us to gauge the specific aspects of workplace surveillance that were most concerning to workers.

Figure 2. Variables used in factorial vignettes.

Concerns about the types of data collected by employers

First, when considering different types of data that could be collected by an employer (“Data Attribute” in Figure 2), respondents thought videos or images of their home workspace were the most problematic, followed by their social media posts and data about their mental and physical health. While concerns about data collected from one’s home—a traditionally private space—are relatively novel, these other types of data are already captured by many employers. For example, social media data is frequently captured during the hiring process to screen potential employees, and algorithms are increasingly used to infer mental health from social media posts.4Stevie Chancellor and Munmun De Choudhury, “Methods in Predictive Techniques for Mental Health Status on Social Media: A Critical Review,” NPJ Digital Medicine 3, no. 43 (2020). Collecting data about one’s physical health, including questionnaires, temperature screenings, and Covid tests, has become commonplace during the pandemic and may continue for some time. Of course, other measures of physical health, such as data collected from fitness trackers, were common before the pandemic and raise important questions about how that data might be used. On the other hand, the least concerning data attributes aligned with the types of data routinely captured in normal work environments, such as metrics about the length of one’s work sessions, the content of work emails, and one’s IP address when accessing work systems. It’s likely workers see these types of data collection as justified because they are clearly linked with productivity and information security.

Concerns about the purposes of data collection

When we look at workers’ concerns related to different uses of their data (“Purpose” in Figure 2), we were surprised that two health-specific outcomes—to reduce healthcare costs for healthy employees and to encourage healthy behaviors—were viewed as the most concerning, while ensuring information security practices were maintained and reducing the spread of disease were viewed as the least concerning. Given the popularity of wellness programs that encourage healthy behaviors—which are usually accompanied by financial incentives for employees who participate—we expected these items to be viewed as less concerning. We speculate that workers might have greater sensitivity to this type of data collection and use, given the increased attention to personal health decisions during the pandemic.

Concerns about who has access to worker data

Workers we surveyed were presented with six categories of company staff that would have access to any data collected as part of the company’s new monitoring program (“Actor” in Figure 2). Respondents were significantly more concerned with their coworkers seeing this data, even when shared through an anonymous dashboard, compared with their supervisor, senior executives, or the IT or HR departments. Thinking about the hierarchical structure of most companies, this suggests that workers are more comfortable with those above them accessing data about them than their peers, as well as those who might have a legitimate reason for viewing the data (in the case of IT and HR personnel). These findings align with Helen Nissenbaum’s framework of privacy as contextual integrity5 Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009More Info → in that this flow of information to certain entities is seen as more appropriate. They also highlight that perceptions of privacy violations fall along a spectrum and should not be treated as all-or-nothing decisions.

Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009More Info → in that this flow of information to certain entities is seen as more appropriate. They also highlight that perceptions of privacy violations fall along a spectrum and should not be treated as all-or-nothing decisions.

Concerns about the timeframe for data collection

“Employees also worry that data collected through monitoring tools can be taken out of context and used against them.”Finally, we surveyed worker concerns about when and where data collection would occur (“Timeframe” in Figure 2). Respondents were most concerned when they were told data collection would continue after they returned to the workplace and least concerned when data collection would only occur while logged into work applications at home. This finding raises important considerations around data minimization, which refers to the practice of only collecting data that is required to complete a task or achieve a stated goal. In this case, some amount of additional surveillance during the pandemic might be deemed acceptable because of the unique nature of the pandemic, but excessive surveillance will likely be viewed with more concern and skepticism. Prior research has highlighted that employers have a responsibility “to justify the collection of particular data in particular contexts,”6Lucas D. Introna, “Workplace Surveillance, Privacy and Distributive Justice,” ACM SIGCAS Computers and Society 30, no. 4 (2000): 33–39. so employers need to carefully consider which monitoring tools to continue using after workers return to the office. Employees also worry that data collected through monitoring tools can be taken out of context and used against them.7Introna, “Workplace Surveillance.”

Where do we go next?

Covid-19 upended work in many ways and forced companies and employees to reconsider best practices for getting work done. This blurring of the public and private spheres through increased surveillance is concerning, as is the potential for such surveillance practices to continue after the pandemic. Our findings provide insights into workers’ perceptions of current workplace monitoring practices and, more importantly, their concerns regarding the potential uses of workplace monitoring technology after the pandemic is over and they return to “normal” working environments. They also raise new questions about how such reductions in privacy and independence at work may have negative outcomes on worker productivity, satisfaction, and well-being.

A recent SSRC report points to the need for research to “evaluate the proliferation of technology-oriented responses that emerged at the height of the pandemic” and to “illuminate the underlying assumptions in the presumed tensions among protecting public health, preserving privacy, and ensuring equity.” While our results provide a useful starting point to address these concerns, there is more work to be done.

Our sample focused on those who could easily transition to remote work during the pandemic, and thus skewed toward traditionally “white collar” workers. But these new forms of surveillance are being deployed across a range of workplaces, raising concerns for surveillance of gig workers, delivery drivers, warehouse workers, and more. Future research will need to explore the types of monitoring being used, whether they are necessary or simply being used to control workers’ every movement, and ways to empower these workers to push back against unnecessary monitoring.

Banner photo: Lianhao Qu/Unsplash.