The coronavirus pandemic constitutes a major threat to many peoples’ lives and physical health. Even if containment is more or less successful in many countries, millions have been infected and more than one million people may be expected to die from the virus by the end of 2020. This existential threat from the new virus has resulted in severe and widespread fears—especially among the elderly and those with pre-existing health conditions, who are most vulnerable to its effects.

However, the political measures effective in containing the virus, such as lockdowns and rules on “social distancing,” have also taken a toll on mental health. Typically, a majority of people display resilience even in times of major crisis. But in the coronavirus crisis, important mechanisms for coping with fears and achieving resilience, such as socializing and other distractions, are unavailable. Among some groups, initial feelings of fear have given way to backlash and anger at lockdown measures, and several countries have witnessed protests and demonstrations.

A more concerning development with regard to mental health, though, is an apparent rise in depressive symptoms during the coronavirus crisis. Early on, studies from China indicated a respective increase.1Cuiyan Wang et al., “Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 5 (2020). Recent results from representative panel surveys, too, show a quite dramatic increase, especially among younger people.

“A previous mental disorder only accentuates the negative mental health effect of the coronavirus crisis.”Part of this increase may be due to recurring depressive episodes, as people with a history of depression lose structure in their daily lives and cannot access adequate care and counselling during the lockdown. However, a previous mental disorder only accentuates the negative mental health effect of the coronavirus crisis.2Ilya M. Veer et al., “Psycho-social Factors Associated with Mental Resilience in the Corona Lockdown” (preprint, submitted April 22, 2020). Given that sufferers of severe chronic depression are less likely to participate in panel surveys, it is safe to assume that many of those who report increased depressive symptoms are experiencing them for the first time in their life.

In many ways, low morale and anxiety among young people seem like adequate responses to the situation in which they find themselves. While they may be (on average) least in danger from the virus itself, young adults are hit hardest by the measures to fight the pandemic. Economic recession and rising unemployment are more worrying to someone just embarking on a career than for those in more secure positions. Being cut off from friends is more challenging for younger people who are often single and more dependent on peer contacts and socializing in larger groups than older adults in more established families. In addition, younger people think in different time spans and so are more inclined to discount the distant in favor of the near future.

We believe that the rise in depressive symptoms among younger people, even if it will not in most cases result in full-blown clinical depression, will have lasting negative effects beyond public health. In particular, we expect the rise in depressive symptoms to damage political trust and efficacy, and patterns of political participation—and thus the resilience of democracy in times of crisis.

Democracy and mental health are not often talked about together, but a growing body of scholarship shows that the two are intimately connected.3→Luca Bernardi and Robert Johns, “Depression and Attitudes to Change in Referendums: The Case of Brexit,” European Journal of Political Research, April 11, 2020.

→Jerome Couture and Sandra Breux, “The Differentiated Effects of Health on Political Participation,” European Journal of Public Health 27, no. 4 (2017): 599–604.

→Claudia Landwehr and Christopher Ojeda, “Depression and Democracy: A Cross-National Study of Depressive Symptoms and Non-Participation,” American Political Science Review (forthcoming).

→Christopher Ojeda, “Depression and Political Participation,” Social Science Quarterly 96, no. 5 (2015): 1226–1243.

→Christopher Ojeda and Julianna Pacheco, “Health and Voting in Young Adulthood,” British Journal of Political Science 49, no. 3 (2017): 1163–1186.

→Christopher Ojeda and Christine Marie Slaughter, “Intersectionality, Depression, and Voter Turnout,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 44, no. 3 (2019): 479–504. Citizens who suffer from depressive symptoms—even if it is not full-blown diagnosable depression—are more politically disengaged than their healthier counterparts. Depression makes citizens less active, less interested, and less confident in politics. This is especially true when participation in politics is more physically and cognitively demanding, such as volunteering for a campaign, than when it is fairly effortless, such as posting about politics on social media.

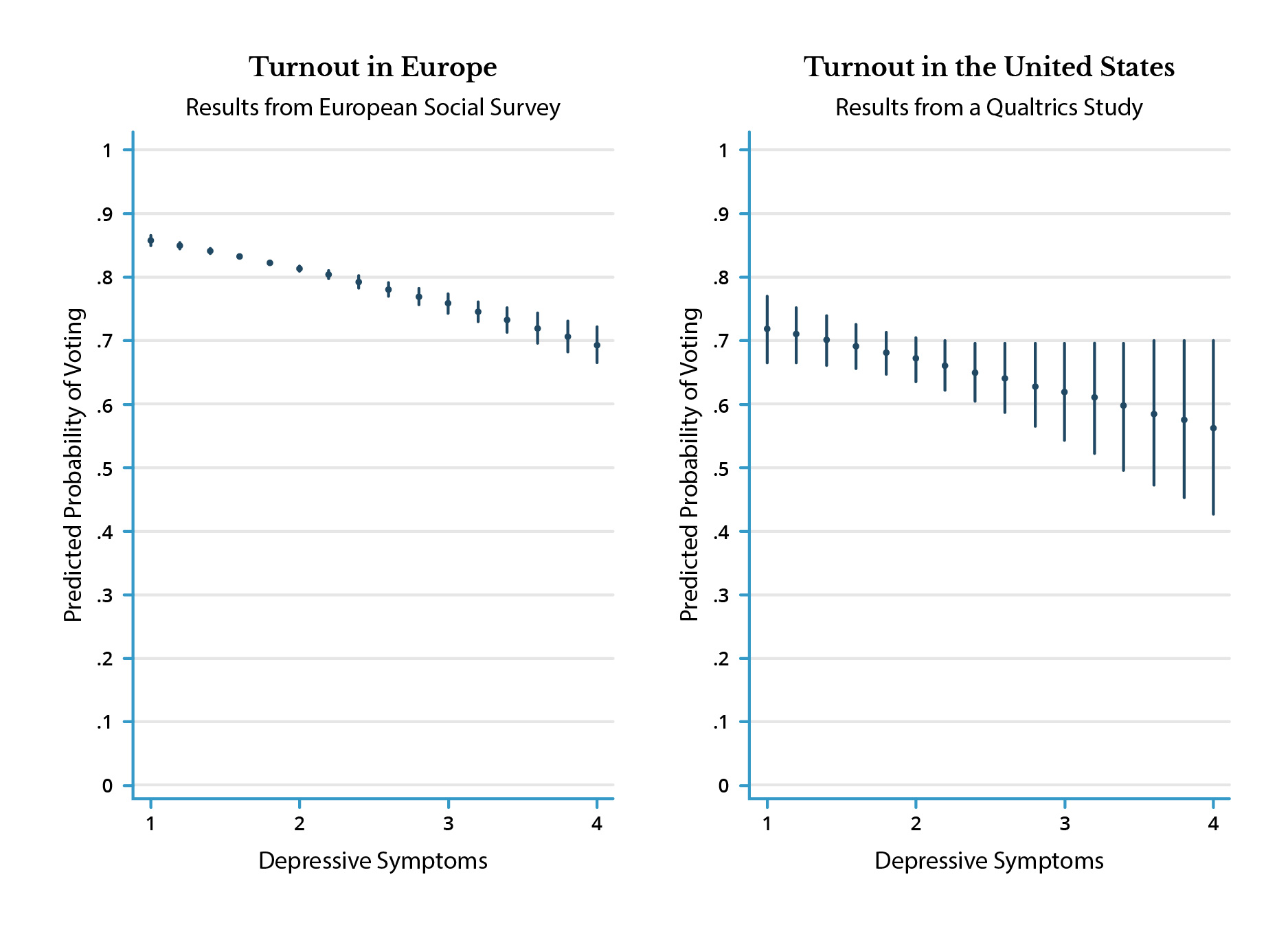

This pattern poses a problem for upcoming elections and, in particular, the US presidential election, because it means that turnout could be significantly down. Setting aside the fear of contracting the coronavirus—which will likely also depress turnout—we conducted analyses of elections in the United States and Europe and found large gaps in turnout between those with and without depression. Figure 1 reports the results of our models by showing the predicted probability of voting across different values of depressive symptoms. Analyzing data from the 2006 and 2012 European Social Survey, we found that a citizen with no depressive symptoms has a 0.86 probability of voting on average, while a citizen with full-blown depressive symptoms has only a 0.69 probability of voting. The predictions for the United States, which are based on an analysis of survey data we collected through Qualtrics, suggest similar levels of decline in the 2018 midterm election.

Worse still is that the dip in turnout caused by increased depressive symptoms among young people may give birth to a generation of nonvoters. Young adulthood is a time to learn about the politics and the procedures that guide participation, whether it is the policy positions of the major parties, the location of voting precincts, or simply registering to vote.4Eric Plutzer, “Becoming a Habitual Voter: Inertia, Resources, and Growth in Young Adulthood,” American Political Science Review 96, no. 1 (2002): 41–56. Our research suggests that depression can impede this learning: teenagers with depressive symptoms were less politically participative in young adulthood, even if their symptoms had completely gone away.5Christopher Ojeda, “Depression and Political Participation,” Social Science Quarterly 96, no. 5 (2015): 1226–1243.

However, in the midst of the Covid-19 crisis, the United States saw a surge of political activity among young adults as part of the Black Lives Matter movement. At first glance, these protests may seem to foretell greater turnout in the upcoming US presidential election, a trend that would run counter to our concerns about depression. We are not so sure, however. As we noted before, depression hinders physically demanding forms of political participation, such as protesting, and so it seems possible that widespread feelings of depression kept many citizens from taking to the streets. So, while the BLM movement may mobilize some new voters, it’s not immediately clear to us that citizens with depression will be part of this trend.

“Between depression and anxiety, turnout in the upcoming presidential election looks grim.”Some decades back, scholars of political behavior widely lamented what seemed to be declining voter turnout in the United States. This supposed trend turned out to be an accounting error,6Michael P. McDonald and Samuel L. Popkin, “The Myth of the Vanishing Voter,” American Political Science Review 95, no. 4 (2001): 963–974. but the urgency of their concerns rings true now. Abstention may reflect underlying dissatisfaction with the system, which at some point becomes so widespread that it morphs into perceptions of illegitimacy. Between depression and anxiety, turnout in the upcoming presidential election looks grim. Unusually low turnout can provide a basis for claims of illegitimacy from the losing side, presenting a threat to democratic stability.

With regard to public health, strategies to reduce the mental health costs of measures taken to fight the spread of the pandemic, such as better access for care and counselling, clearly seem in order. But with regard to the resilience of our democracy, we need to find strategies to reduce the impact of depressive symptoms on political participation and to re-activate citizens in the aftermath of the crisis.

Banner image: Tim Evanson/Flickr.

References:

→Jerome Couture and Sandra Breux, “The Differentiated Effects of Health on Political Participation,” European Journal of Public Health 27, no. 4 (2017): 599–604.

→Claudia Landwehr and Christopher Ojeda, “Depression and Democracy: A Cross-National Study of Depressive Symptoms and Non-Participation,” American Political Science Review (forthcoming).

→Christopher Ojeda, “Depression and Political Participation,” Social Science Quarterly 96, no. 5 (2015): 1226–1243.

→Christopher Ojeda and Julianna Pacheco, “Health and Voting in Young Adulthood,” British Journal of Political Science 49, no. 3 (2017): 1163–1186.

→Christopher Ojeda and Christine Marie Slaughter, “Intersectionality, Depression, and Voter Turnout,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 44, no. 3 (2019): 479–504.