People in the United States, though many are still homebound and separated in response to social distancing orders, are nonetheless finding ways to connect and support each other. Emergent, hyperlocal, “mutual aid” groups are organizing in every state in order to offer support to their neighbors in the form of cooking meals, running errands, caring for children and pets, helping with essential chores, and keeping each other company via phone or video conference. Using tools that include Google Docs, Facebook, Slack, and WhatsApp, these groups are connecting their neighborhoods and working to match their skills and resources to the needs of their communities, which are emerging as a result of the ongoing pandemic. These types of efforts are common during moments of crisis. Disaster researchers have argued for decades that, contrary to popular myths about looting and panic, most people act calmly, rationally, and altruistically during emergencies. The current mobilizations are, indeed, part of a much longer history of both online and offline organizing and self-help work. The specific ways in which mutual aid groups are using technology to respond to this disaster offers many remarkable insights for researchers who study these topics.

“Launched in the mid-2000s, crisis informatics has achieved widespread recognition for major contributions to understanding how newer technologies like the internet and social media enable new forms of cooperation and information sharing during emergencies.”Crisis informatics is a multidisciplinary area of study that draws from the social sciences of disaster and computer and information sciences to examine the myriad ways in which technology shapes societal relationships to disaster.1A guided bibliography to crisis informatics research relevant to Covid-19 can be found at here. Launched in the mid-2000s, crisis informatics has achieved widespread recognition for major contributions to understanding how newer technologies like the internet and social media enable new forms of cooperation and information sharing during emergencies.2Leysia Palen and Kenneth M. Anderson, “Crisis Informatics—New Data for Extraordinary Times,” Science 353, no. 6296 (2016): 224–225. Research in this area has also demonstrated that the data produced by users of these tools give researchers novel insights into long-standing questions about human behavior in disaster situations. Recently, crisis informatics researchers have also brought critical and design-oriented perspectives to a wider range of disaster technologies including humanitarian situation reports3Megan Finn and Elisa Oreglia, “A Fundamentally Confused Document: Situation Reports and the Work of Producing Humanitarian Information” in Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery, 2016), 1349–1362. and postdisaster damage assessments.4Robert Soden and Austin Lord, “Mapping Silences, Reconfiguring Loss: Practices of Damage Assessment & Repair in Post-earthquake Nepal,” Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 2, no. CSCW (2018): 1–21. Though we are still in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic and the activities of local mutual aid groups are evolving as the situation changes, there are already some emerging features of this activity that we should pay attention to from the perspective of crisis informatics research.

Mutual aid and disaster response

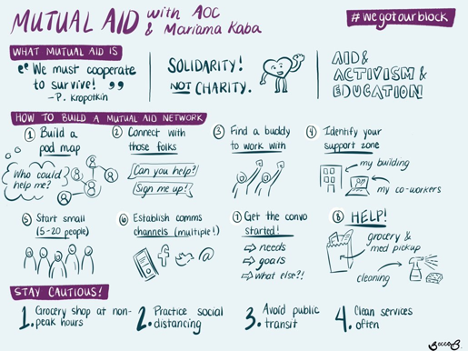

The framing of community self-help in disaster as mutual aid has grown in the United States in recent years. Whereas grassroots collective efforts to respond to disaster are near universal, referring to this behavior explicitly as mutual aid began to gain widespread prominence during the Occupy Sandy Movement in 2012. The practices of mutual aid groups, as well as the values and beliefs that drive them, are distinct from some of the more celebrated efforts at volunteer digital humanitarian response to recent disasters. Drawing on the rich history of mutual aid work in the United States, organizers of the current activation emphasize solidarity instead of charity models of assistance,5Dean Spade, “Solidarity Not Charity: Mutual Aid for Mobilization and Survival,” Social Text 38, no. 1 (2020): 131–151. deploy nonhierarchical/horizontal organizing strategies, and put forth a notion of expertise that centers the agency and knowledge of the people who are most impacted by a disaster. In doing so, these groups foreground the political dimensions of disaster vulnerability, impacts, and recovery processes—often putting them in complex relationships with formal emergency response and social services. The mission of the mutual aid response has been to serve the needs of a community impacted by the crisis while building the networks and vision necessary to accomplish more systemic change.

Though the term “mutual aid” is often traced back to the work of Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin and fraternal societies in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, current manifestations in the United States more frequently recall the survival programs organized by the Black Panther Party and mutual aid efforts in LGBTQ communities, both of which draw close connections between meeting the material needs of marginalized communities with grassroots movement toward political change. The lineage is evident in the fact that so many mutual aid groups are also active in the Black Lives Matter movement and pressuring elected officials to enact more equitable and robust government response to the crisis. While some groups are new, many are built upon existing organizing infrastructures, such as the prison abolition movement, anticolonization work,6→Nick Estes, Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance (Verso, 2019).

→Adriana Garriga-López, “Puerto Rico: The Future in Question,” Shima 13, no. 2 (2019): 174–192. disability justice communities, and the networks formed during Occupy Wall Street. Some of the policies they advocate for include sweeping changes to the criminal justice and healthcare systems, combatting gentrification, student debt cancellation, and other measures aimed at reducing communities’ vulnerability to future disasters.

As is common with emergent mobilization to disaster, mutual aid organizations are finding creative ways to stitch together everyday technologies to meet extraordinary demands. Prior work in crisis informatics has documented how groups appropriate available technological resources to self-organize, gather and share information through distributed sensemaking processes, mobilize needed expertise, and otherwise coordinate complex collaboration in ways that can be hard to predict.7For example, see Kate Starbird and Leysia Palen, “‘Voluntweeters’: Self-Organizing by Digital Volunteers in Times of Crisis,” in CHI ’11: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery, 2011): 1071–1080; and Joanne I. White and Leysia Palen, “Expertise in the Wired Wild West,” in CSCW ’15: Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery, 2015): 662–675. One phenomenon to note in the current mobilizations is the highly decentralized activities, with hundreds of local groups acting concurrently, and sharing tools and methods such as Google Form templates, flyer designs, and aid-request tracking methods horizontally across groups. This shares resemblance to the role that design patterns play in user-interface development and computer programming, easing onboarding of new groups while allowing for local experimentation and customization. Further understanding into how these activities are accomplished can inform both basic research in disaster and organizational studies as well as provide important insights for technology designers.

Given the informality and decentralization of the local response efforts, accurate accounting of the magnitude of their organization and impact is effectively impossible. Major media outlets have reported on these activities in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Canada, and across North America. In New York alone, hundreds of people have added their names to volunteer registries or listed themselves as “pod leaders,” or organizers who are mobilizing their neighbors. Scanning the dozens or more newly created mutual aid Facebook groups in New York City alone shows thousands of volunteers, posting their willingness to help in various ways donating hundreds of thousands of dollars to the numerous crowdfunding campaigns that have been launched since March. The details of where and how requests are being met and support provided are often sorted out through private messages, texts, and phone calls, meaning researchers don’t have access to what happened. The size and impact of the informal volunteer response should be evaluated as one considers an iceberg—with the visible portions suggesting a much greater mass that is just out of view. Attempts to compare this activity to the formal response of government and social service agencies, where accounting mechanisms are well-established, should be approached with care.

Crisis informatics research and mutual aid

“Technologies like Facebook, Twitter, and email lists are powerful tools to scaffold social networks but contain their own forms of exclusions.”The difficult and important work that mutual aid groups are undertaking raise many questions with which crisis informatics research might productively engage. First, who is being included in mutual aid activities? Who is being left out? Do these groups reach the most vulnerable members of the community, like houseless folks or the elderly? Are the precariously employed delivery drivers, bartenders, and waiters—who, though vital contributors to the neighborhoods where they work, may not necessarily live in them—included in mutual aid efforts? To what extent are emergent groups connecting with, and finding ways to ally with, local social service agencies, churches, and local businesses? Technologies like Facebook, Twitter, and email lists are powerful tools to scaffold social networks but contain their own forms of exclusions.8Taylor Shelton et al., “Mapping the Data Shadows of Hurricane Sandy: Uncovering the Sociospatial Dimensions of ‘Big Data’,” Geoforum 52 (March 2014): 167–179. For example, Slack, a tool used by many local groups in the current crisis, is particularly opaque in that, unlike some of these other tools, Slack workspaces have no built-in public-facing element. The affordances of chosen technologies, along with the strategies used by organizers in their application, and the demographic makeup of NYC neighborhoods will strongly impact groups’ ability to effectively engage in mutual aid strategies.

Second, we should pay particularly close attention to how online mutual aid organizations’ discursive work: articulates the kind of disaster this pandemic is, focuses attention on a particular set of impacts, and, in so doing, delimits the sorts of solutions we might imagine. It is already clear that, unlike government responses—which emphasize monitoring, testing, and control of population movements—mutual aid groups are centering their attention on many of the social vulnerabilities that create uneven susceptibilities to the health and economic impacts of the coronavirus disaster. Unlike the City of Chicago, for example, which is threatening to fine its sick or even symptomatic residents for going outside, Los Angeles, which will prosecute failure to observe proper social distancing as a misdemeanor, or the numerous other states and cities that are using punitive action (which will no doubt be applied unequally) to promote public safety, mutual aid organizations are seeking to build the social support infrastructure that would make it easier for people to stay in their homes. Tracing the discontinuities between competing understandings of the coronavirus disaster can help bring attention to the contours of power in the politics of disaster, reveal solidarities and fissures amongst disaster publics, and highlight the perspective and needs of the most vulnerable elements of society.

Another urgent question for crisis informatics researchers is how the features of this hazard, a particularly nasty and infectious virus and its economic fallout, shape the digital mobilization and information behaviors that communities undertake in response. The pandemic has a unique spatial structure, perhaps taking on more of a network shape than something which might be more easily mapped out in cartesian space. This has an immediate effect on convergence activity. If there is no meaningful demarcation of the disaster-affected area and the zone of convergence is potentially anywhere, the kinds of social and technological behaviors that emerge in response will look different, and potentially more like mutual aid than in other kinds of hazards. The temporal rhythm of the pandemic is also different than the punctuated, though long-lasting impacts, of earthquakes, potentially giving emergent mutual aid groups more time to mobilize but also lengthening the response period, creating opportunities for both iteration and learning as well as volunteer burnout. Recent work in crisis informatics has called for greater attention to how different hazards influence information-seeking and -sharing behavior.9Leysia Palen and Amanda L. Hughes, “Social Media in Disaster Communication,” in Handbook of Disaster Research, eds. Havidán Rodríguez, William Donner, and Joseph E. Trainor (Springer, 2018), 497–518. The current crisis would seem an important chance to do this.

“Methods, protocols, and tools for data protection that can be deployed by local, emergent organizations represent an important area of research, design, and an opportunity to support ongoing mutual aid work.”An area for concern about the informal and grassroots quality of the mutual aid response, as it is constituted so far, relates to data security and the privacy of participants. At present, many groups are collecting and internally sharing full names, addresses, contact details, and sensitive information about disability and socioeconomic status without clear guidelines for how to protect this information and when to dispose of it. At the same time, privacy groups are sounding alarms about governments around the world using the pandemic disaster to increase their legal and technical capacity to surveil their citizens. In the United States, companies including Facebook, Google, and Palantir have met with the Trump administration to discuss the use of smartphone location data to trace and combat the spread of Covid-19. While companies claim that any data used for this purpose would be anonymized, the track record of these companies when it comes to handling user data does not suggest optimism. Difficult questions about informed consent, privacy tradeoffs, and the potential misuses of sensitive data are thus in need of answers right now at all levels of the response. Methods, protocols, and tools for data protection that can be deployed by local, emergent organizations represent an important area of research, design, and an opportunity to support ongoing mutual aid work.

A potential, but so far unevaluated, role that mutual aid groups are poised to play is in sharing information and amplifying communications related to Covid-19. Mutual aid organizations, in addition to sharing material resources amongst participants, are also sharing information about events in their communities, access and availability of social services, and advice on reducing the spread of the disease. In doing so, they may also contribute to either combatting, or mistakenly spreading, misinformation about the disaster. Crisis informatics research has over the past several years begun to look closely at how the spread of rumors and false information, long a challenge in disasters, has changed as a result of online platforms.10Kate Starbird, Ahmer Arif, and Tom Wilson, “Disinformation as Collaborative Work: Surfacing the Participatory Nature of Strategic Information Operations,” in Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 3, CSCW, eds. Airi Lampinen, Darren Gergle, and David A. Shamma (New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery, 2019): 127. These questions, always important, take on increased importance in the United States where the federal government and major media outlets are also regularly delivering false information to the public. It is worth asking how local mutual aid organizations can act to inoculate their participants and other community residents against misinformation through regularly sharing trusted information, developing group norms against sharing unverified claims, and quickly identifying and removing problematic posts from shared online spaces like Facebook groups or Slack channels. Early observations have revealed each of these behaviors, but more systematic study is necessary.

Looking ahead

The Ancient Greek roots of the word crisis mean a major decision or turning point. So we are, at present, in a liminal period where political, economic, and social infrastructures that shape our society are revealed as far less permanent and immovable than we tend to assume. Moments of crises are thus what Bowker calls “infrastructural inversions,”11Geoffrey C. Bowker, Karen Baker, Florence Millerand, and David Ribes, “Toward Information Infrastructure Studies: Ways of Knowing in a Networked Environment,” in International Handbook of Internet Research, eds. Jeremy Hunsinger, Lisbeth Klastrup, and Matthew Allen (Dordrecht: Springer, 2009): 97–117. or opportunities for revealing and remaking the fundamental, if often difficult to trace, systems that govern collective life. Crisis informatics, as a body of research and a community of engaged scholars, can engage with this opportunity while also progressing and growing our field in exciting directions. As in every disaster, conducting engaged and ethical research alongside and with the communities grappling with the worst of its impacts is extraordinarily challenging. The practices and principles of mutual aid are receiving widespread attention at the moment, but have been part of the survival strategies of many communities for generations. If we as researchers rush into this space without taking with us the best of our knowledge from disaster studies12Jennifer Henderson and Max Liboiron, “Compromise and Action: Tactics for Doing Ethical Research in Disaster Zones,” in Disaster Research and the Second Environmental Crisis, eds. James Kendra, Scott G. Knowles, and Tricia Wachtendorf (Springer, 2019), 295-318. and computing research13→Lynn Dombrowski, Ellie Harmon, and Sarah Fox, “Social Justice-Oriented Interaction Design: Outlining Key Design Strategies and Commitments,” in Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems (New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery, 2016), 656–671.

→Ihudiya F. Ogbonnaya-Ogburu et al., “Critical Race Theory for HCI,” in Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery, 2020), 1–16.

→Desmond U. Patton, “Social Work Thinking for UX and AI Design,” Interactions 27, no. 2 (2020): 86–89. about how to do this well, then this may be an opportunity lost.

The coronavirus pandemic will eventually come to an end. When it does, the world will be irrevocably changed. Despite the hopes of many for an eventual return to “normal,” it is clear that such a return is neither possible nor desirable. Returning to normal, after all, would mean a return to the very conditions of vulnerability that allowed this disease to become a disaster. Naomi Klein has written how, time and again, such opportunities have been seized by neoliberals and the right to advance austerity politics and radical free-market capitalism. The mutual aid groups arising in response to the coronavirus prefigure a different sort of future. Legal theorist Dean Spade highlights the potential of the radical vision of politics at the root of contemporary mutual aid movements, arguing that it represents a “form of political participation in which people take responsibility for caring for one another and changing political conditions, not just through symbolic acts or putting pressure on their representatives in government but by actually building new social relations that are more survivable.”14Spade, “Solidarity Not Charity,” 136. The extent to which they will be successful in helping their communities weather the pandemic while building the infrastructure for a better world is yet to be determined, but crisis informatics should be a part of this work.

This essay was written during my time as a postdoc at Columbia University, an organizer with Morningside Mutual Aid in Manhattan, and a volunteer with Mutual Aid NYC’s oral history team. Leysia Palen, Co-Risk Labs, and members of the Natural Hazards Center’s CONVERGE working group Hyper-Local and Emergent Mutual-Aid Responses to Covid-19 provided feedback on early drafts of this post.

Banner photo credit: Fresno Central SDA/Flickr

References:

→Adriana Garriga-López, “Puerto Rico: The Future in Question,” Shima 13, no. 2 (2019): 174–192.

→Ihudiya F. Ogbonnaya-Ogburu et al., “Critical Race Theory for HCI,” in Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery, 2020), 1–16.

→Desmond U. Patton, “Social Work Thinking for UX and AI Design,” Interactions 27, no. 2 (2020): 86–89.

Pingback: COVID-19 and Victim Blaming in the U.S. – Global Challenges Insights

Pingback: How the Coronavirus Exposed Systemic Inequalities within the U.S. – Public Anthropology and Global