Welfare states in Western democracies have come under increasing pressure in the last decades, as they simultaneously face new social demands and growing fiscal constraints. Changing family structures and a massive entry of women into the labor market have increased the need for (public) childcare and elderly care facilities, while the changing structure of postindustrial labor markets has created a growing segment of nonunionized workers—also referred to as labor market outsiders—with precarious employment situations. The demands associated with these “new social risks” have emerged at a time when governments continue to be confronted with growing debt levels, increasing economic globalization, and an aging population, all of which restrict their fiscal resources.1Peter Taylor-Gooby, “New Risks and Social Change,” in New Risks, New Welfare: The Transformation of the European Welfare State, ed. Peter Taylor-Gooby (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 1–28.

As a response to these developments, many European welfare states have undergone a massive restructuring that is characterized, despite large cross-country variations, by a common reform trajectory toward a more activating, or “social investment” welfare state.2Kees van Kersbergen and Anton Hemerijck, “Two Decades of Change in Europe: The Emergence of the Social Investment State,” Journal of Social Policy 41, no. 3 (2012): 475–92. This welfare state restructuring typically involves a shift from traditional income replacement policies, such as pensions and unemployment insurance, toward increasing labor market participation, human capital investment, and cost containment. Since labor market participation can be fostered both by public services that increase employment opportunities, such as public childcare or job training, and by the introduction of work obligations and stricter conditions for benefits, this restructuring involves both retrenchment and expansion. Against this backdrop, it is not surprising the distributional consequences of this restructuring are highly debated: whereas optimistic observers see in the “social investment strategy” the opportunity to fight poverty and social exclusion through employment and the employability of workers, a growing number of scholars worry over its consequences for economic inequality.3Bea Cantillon and Wim Van Lancker, “Three Shortcomings of the Social Investment Perspective,” Social Policy and Society 12, no. 4 (2013): 553–64.

What drives this activation turn in welfare politics? Functional pressures, like new societal demands or tight public budgets, do not automatically translate into policy change, but are mediated and influenced by political factors. Even under fiscal pressure, for instance, governments have to decide which policies they prioritize, or which social risks they want to address most. In what follows, I argue that representational inequality along social class lines is one factor that helps understand the current trends in welfare state restructuring.

Unequal political responsiveness and its implications for social policymaking

Inequality in political representation has received much scholarly and public attention in recent years. A number of empirical studies have shown that policy decisions tend to be skewed in favor of upper income groups, both in the United States and in European democracies.4→Larry M. Bartels, Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008).

→Martin Gilens, Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America (New York: Russell Sage Foundation; Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012).

→Lea Elsässer, Svenja Hense, and Armin Schäfer, “Government of the People, by the Elite, for the Rich: Unequal Responsiveness in an Unlikely Case” (MPIfG Discussion Paper 18/5, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne, June 2018). This not only violates the normative principle of political equality, but may also have profound consequences for the direction of policies passed in legislatures. In his contribution to the Democracy Papers, for instance, Larry Bartels shows how in 30 Western democracies government spending on social policy reflects the preferences of affluent citizens, and is uninfluenced by the views of the poor, resulting in lower spending on health, unemployment, pensions, and other major programs.

Apart from a few studies, however, most responsiveness scholars do not systematically assess the impact of representational inequality on the content of policy decisions. What kinds of policies are adopted if political decisions predominantly reflect the preferences of the upper classes? This question is particularly relevant to welfare state politics, since political opinions between rich and poor usually diverge quite strongly in this area. And, as new risks and demands emerge, conflicts about the welfare state have become increasingly multidimensional and go beyond the simple question of “more” or “less” welfare.

The German reform trajectory: A strong shift toward activation

To study this shift, I empirically assess political responsiveness in Germany toward different social classes in major welfare reforms since the 1980s. Germany constitutes an interesting case study. Its welfare system underwent transformative changes in the last decades: once the prototype of a “conservative,” traditionalist welfare regime, with a strong focus on income and status protection, it has witnessed a paradigm shift toward labor market activation.5→Martin Seeleib‐Kaiser, “The End of the Conservative German Welfare State Model,” Social Policy & Administration 50, no. 2 (2016): 219–40.

→Wolfgang Streeck, Re-Forming Capitalism: Institutional Change in the German Political Economy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

Major reform activity started in the mid-1990s, with a couple of reforms aimed at cutting unemployment benefits and increasing pressure on the (long-term) unemployed to take up work. While these reforms only marked the beginning of the paradigm shift, the activation turn increased in the early 2000s with major cutbacks in public pension and unemployment benefits, a strengthening of the private pension system, and a further tightening of social benefits eligibility. Since the mid-2000s, however, these rather negative incentives to take up work have been increasingly accompanied by an expansion of programs and services that reconcile work and family, such as a paid parental leave program and a massive expansion of public childcare. The late 2000s witnessed both further cutbacks in social insurance programs, such as an increase of the retirement age to 67, and some expansions, such as the introduction of a statutory minimum wage. Taken together, the German reform trajectory can be characterized by major cuts in the traditional social insurance programs and an increase in work incentives, combined with an expansion of social investment policies aimed at work-family reconciliation.

The research design

Who favored this reform trajectory? Moreover, what parts of the restructuring process were most contested? Building on an original dataset that includes detailed information on public opinion and corresponding political reform decisions, I examine whether and to what extent unequal responsiveness underlies the restructuring of German welfare. Such an in-depth analysis of this policy field also allows us to explore whether certain kinds of policies are more likely to be adopted if specific cross-class coalitions support them.

The analysis is based on the database “Responsiveness and Public Opinion in Germany” (ResPOG), which I set up with two colleagues as part of a broader research project on political responsiveness.6For a more detailed description of the data set, see Elsässer, Hense, and Schäfer, “Government of the People, by the Elite, for the Rich.” It includes information on public opinion on more than 800 policy proposals and the respective political decisions. The public opinion information is obtained from two representative German surveys, and survey items typically ask for agreement/disagreement on a policy proposal that was publicly discussed at the time of the question. For each of these proposals, the database includes the share of agreement in different income and occupational groups. Since income data is only available for a subset of questions, I use occupational groups as the main measure of social stratification. Due to Germany’s specific occupational structure, civil servants and the self-employed (i.e., business owners, lawyers, or journalists) are used as the “upper class” occupational groups. Compared to white collar employees and workers, they display the highest average incomes. Workers and lower-grade employees, in contrast, are categorized as “lower class” occupational groups.

In order to analyze whose preferences the German reform trajectory reflects, I compare the policy preferences of different occupational groups to the major social policy reform decisions taken by the German parliament since the early 1980s. For each major reform, I identify the survey question(s) addressing a reform’s policy proposals. Based on the survey data, I compile for each occupational group whether a majority supported or opposed the respective reform.

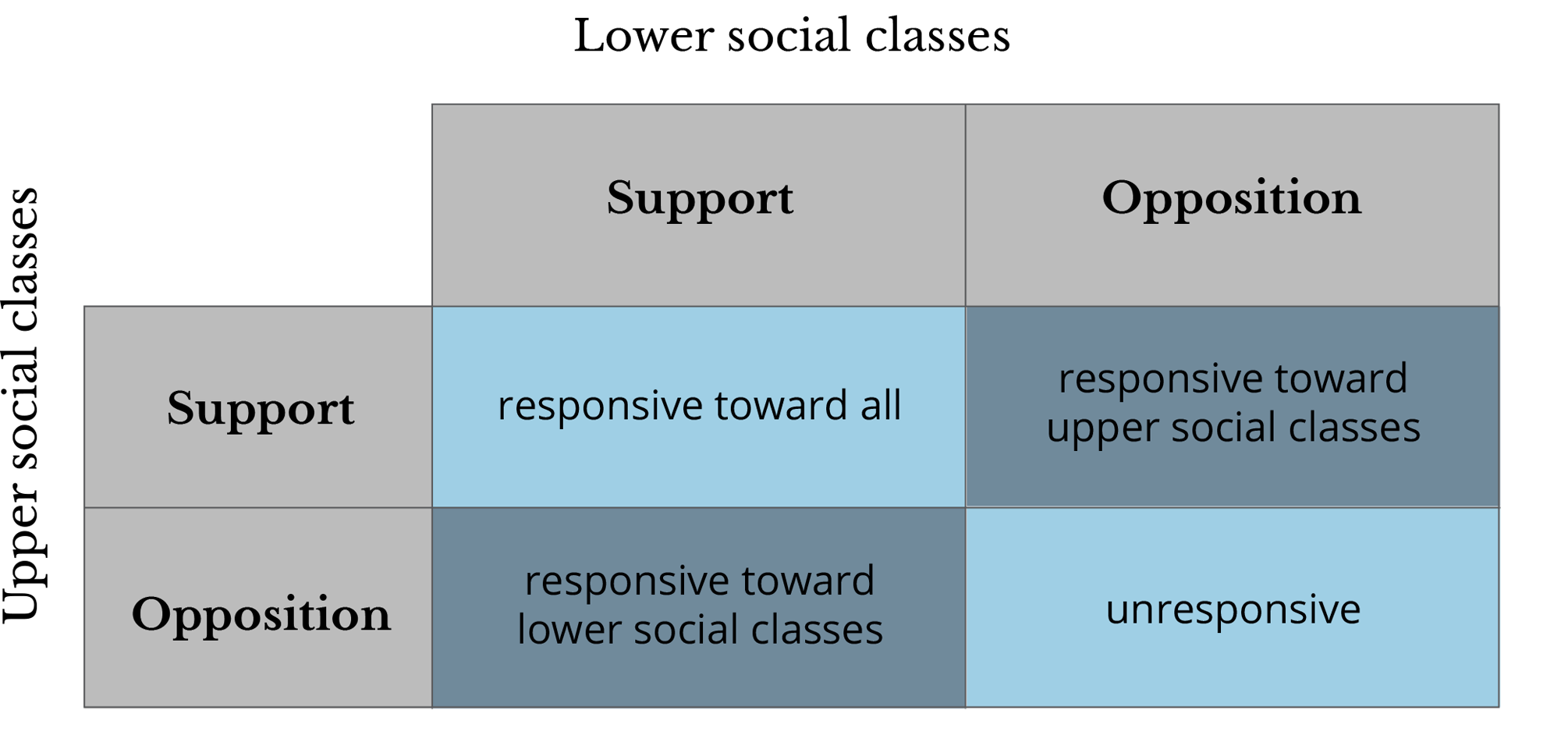

Table 1: Assessment of political responsiveness

In order to assess political responsiveness, I categorize each reform according to the scheme displayed in table 1.7A reform is classified as responsive toward upper social classes if the self-employed and/or civil servants agreed to it, but workers and lower-grade employees opposed it. Conversely, a reform is categorized as responsive toward lower social classes if it was supported by the working class but opposed by the upper occupational groups. If all social classes showed majority support for a reform, it was categorized as responsive toward all. Likewise, a reform was classified as nonresponsive if both groups opposed it.

Unequal responsiveness and welfare state change in Germany

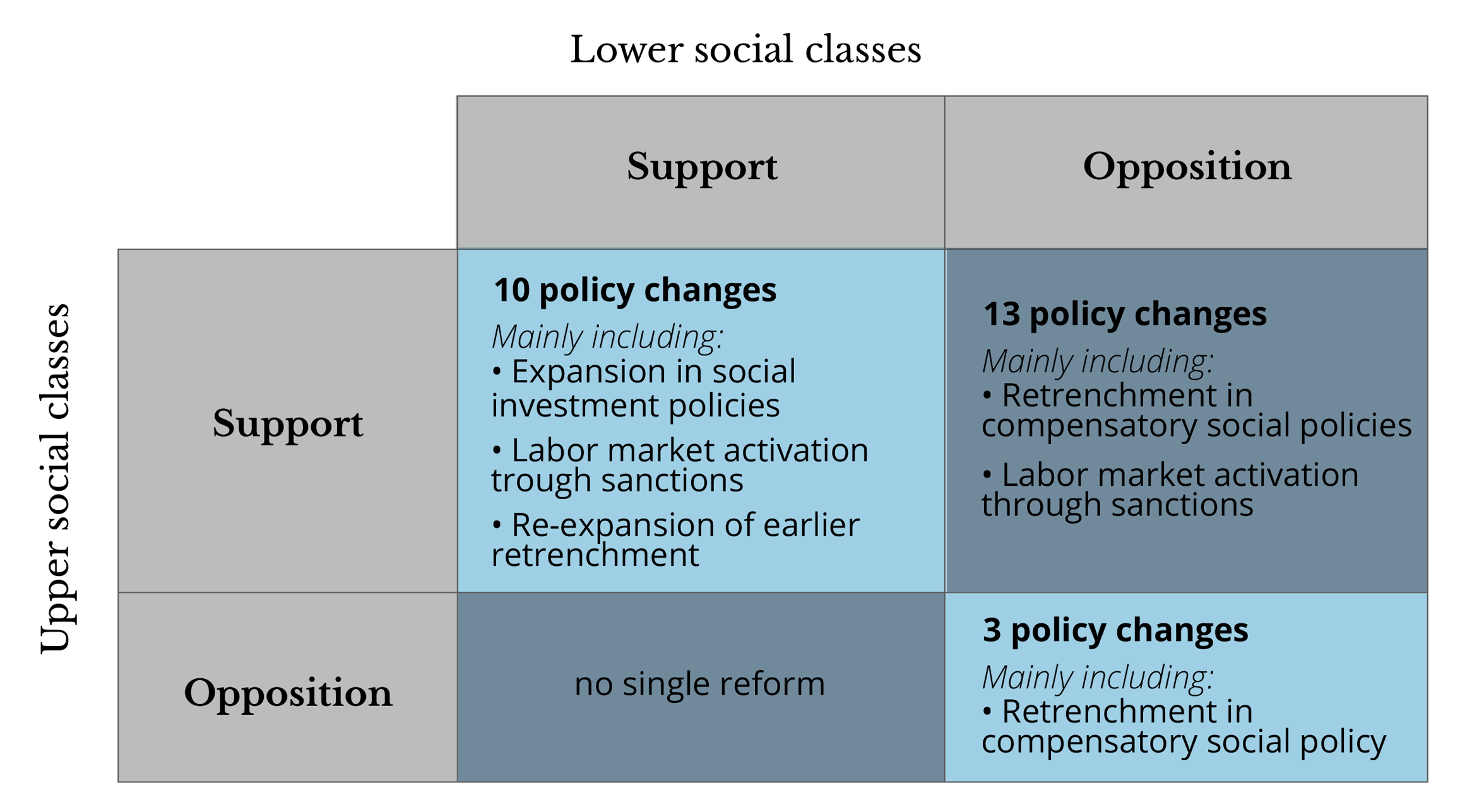

The results are visualized in table 2, showing the number and content of the reforms in each quadrant. Based on this illustration, we can make several important observations. First, and most importantly, the analysis reveals a clear pattern of unequal responsiveness, with political decisions clearly tilted in favor of the upper classes. Whereas the vast majority of reforms found support in the upper occupational groups, only 10 reforms were in line with the preferences of the working class. Taking a look at only those reforms that were contested, the representational bias becomes even more visible: while 13 reform decisions were supported by the upper classes but opposed by the lower ones, no single policy change was exclusively responsive to workers and lower-grade employees. Putting it differently: no single proposal endorsed by the less-advantaged groups passed without the support of the better-off.

“Of those reforms solely responsive toward the upper classes, almost all included retrenchment in the field of compensatory social policy.”When looking at the contents of the reforms in the different quadrants, a further interesting pattern emerges. Of those reforms solely responsive toward the upper classes, almost all included retrenchment in the field of compensatory social policy. Cutbacks in unemployment insurance or the partial privatization of the pension system all were in line with the preferences of the self-employed and civil servants, but opposed by the workers and lower-grade employees. Similarly, the reforms fostering activation by sanctions found more support among the upper classes than among workers, even though some of these reforms found majoritarian support in all occupations groups. In the beginning of the 2000s, for instance, all groups backed a proposal to cut young adults’ unemployment benefits if they refused to relocate to accept a job offer.

Table 2: Unequal responsiveness in welfare state politics in Germany

Third, expansionary policies were only adopted if not only the lower classes but also the civil servants and the self-employed endorsed the proposal. This is true for all expansions in social policy programs during the period under study. The largest genuine expansion of social policy programs has taken place in the field of work-family policies, such as the massive expansion of public childcare places for children younger than three years old, which went into effect in 2013. These new measures to support reconciliation of work and family obligations cater to political needs and demands that previous welfare state programs did not address. They are backed by a rather strong societal consensus, whereas the conflict line between lower and upper classes runs along more traditional programs aimed at income protection.

The mutual reinforcement of political and social inequality

Taken together, these findings show that Germany’s major reform decisions reflected the preferences of the better off, who mainly supported a reform trajectory toward a more activating welfare state. Lower occupational groups, in contrast, only saw their preferences politically enacted when they aligned with those of the upper classes. This constant unequal responsiveness becomes even more troubling when we take into account that different party coalitions were in government during the period under study. The representational deficit of the lower classes was not adequately addressed by any party in government, which points to a systematic problem of political representation.

“Even though the demand for these policies is high across all social classes, there is growing evidence that the middle and upper classes disproportionally benefit from the expansion of these new programs.”Since not all reforms were equally disputed, parts of the welfare state restructuring also found majority support among workers and lower-grade employees. Apart from some (re-)expansions of parts of the social security programs, this is especially true for the introduction of new social investment policies that reconcile work and family. However, even though the demand for these policies is high across all social classes, there is growing evidence that the middle and upper classes disproportionally benefit from the expansion of these new programs. Upper-income families, for instance, make more use of public childcare services than families with lower incomes, and this unequal uptake is often due to structural obstacles such as limited availability or affordability.8Emmanuele Pavolini and Wim Van Lancker, “The Matthew Effect in Childcare Use: A Matter of Policies or Preferences?” Journal of European Public Policy 25, no. 6 (2018): 878–893. In sum, while retrenchment in traditional social security programs hits lower social classes most, because they are most in need of income protection, they seem to benefit least from the expansion of “new” welfare policies. In this way, political and economic inequality tend to reinforce each other.

References:

→Martin Gilens, Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America (New York: Russell Sage Foundation; Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012).

→Lea Elsässer, Svenja Hense, and Armin Schäfer, “Government of the People, by the Elite, for the Rich: Unequal Responsiveness in an Unlikely Case” (MPIfG Discussion Paper 18/5, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne, June 2018).

→Wolfgang Streeck, Re-Forming Capitalism: Institutional Change in the German Political Economy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).