We face an era of disinformation where algorithmic networks in our social media spheres electrify millions of brains to amplify emotions, anger, and distrust.

In the Unites States, the anger of African American communities toward police violence has been exploited by Russian troll factories delocalized to Ghana. In India’s West Bengal region, Rohingya refugees, who fled exactions in Myanmar, are now demonized in violent speech that rapidly metastasize on WhatsApp. In South Africa and Kenya, disinformation and hate speech manufactured, in part, by political elites, inflamed the racial and socioeconomic divisions that have plagued both countries for decades.

Information disorders1The International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) relies on Claire Wardle and Hossein Derakhshan to frame information disorder as a structural phenomenon, including an agent, message, and interpreter, that “contaminates public discourse, working as a pollutant in the information ecosystem.” See Claire Wardle and Hossein Derakhshan, Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policymaking (Strasbourg: Council of Europe, 2017). are an existential threat to democracy, increasingly interfering with the course of elections and undermining citizens’ political agency. In Kenya’s 2013 and 2017 elections, divisive and inflammatory online propaganda, including graphic violence, targeted ethnic and socioeconomic population subgroups, invading mobile phone and social media networks as well as traditional media.2→Nanjala Nyabola, “In Kenya, Election Manipulation Is a Matter of Life and Death,” The Nation, March 28, 2018.

→Privacy International, “Further Questions on Cambridge Analytica’s Involvement in the 2017 Kenyan Elections and Privacy International’s Investigations,’’ Privacy International, March 27, 2018.

→Robert Muthuri et al., Biometric Technology, Elections, and Privacy: Investigating Privacy Implications of Biometric Voter Registration in Kenya’s 2017 Election Process (Nairobi: Centre for Intellectual Property and Information Technology Law, Strathmore University, 2018).

→Nanjala Nyabola, “Texts, Lies, and Videotape,” Foreign Policy, August 1, 2017.

Each election saw more refined and precise strategies for controlling spheres of information and exploiting political and emotional messaging targeted at segmented communities. Such strategies were crafted with the support of two foreign data-analytics companies, Cambridge Analytica and the SCL Group, that profiled and influenced voters’ behaviors. Their prime targets were young Kenyans who had grown up in a world of social networks. Yet, major political parties, the ruling Jubilee party and the opposing National Super Alliance (NASA), had also built and deployed widespread communication architecture to target specific segments of the Kenyan population.

“The era we face—where artificial intelligence (AI) and data-capture technologies converge to analyze our digital bodies and minds—is an epistemic revolution as much as a technological one.”Just as the internet has reshaped commerce, politics, social fabrics, and the stories we tell, it now interferes more directly than ever with how we process and interpret knowledge and information. The era we face—where artificial intelligence (AI) and data-capture technologies converge to analyze our digital bodies and minds—is an epistemic revolution as much as a technological one. States and corporations are increasingly partnering to monitor populations’ behaviors and their information networks. Yet, many nations lack the necessary approaches to regulate these technologies, and international organizations like the United Nations (UN) have yet to provide normative leadership to help promote populations’ data protection and therefore protect human rights.

To make sense of this transformative shift, there is an urgent need to analyze its nature, identify its rules, understand its effects, and catalogue existing oversight gaps. Based on recent research, this essay aims to examine the role international tech companies and world power dynamics play in the proliferation of mis/disinformation in Africa, with a look at present challenges to global governance and potential UN responses.

Converging technologies and new forms of biopower

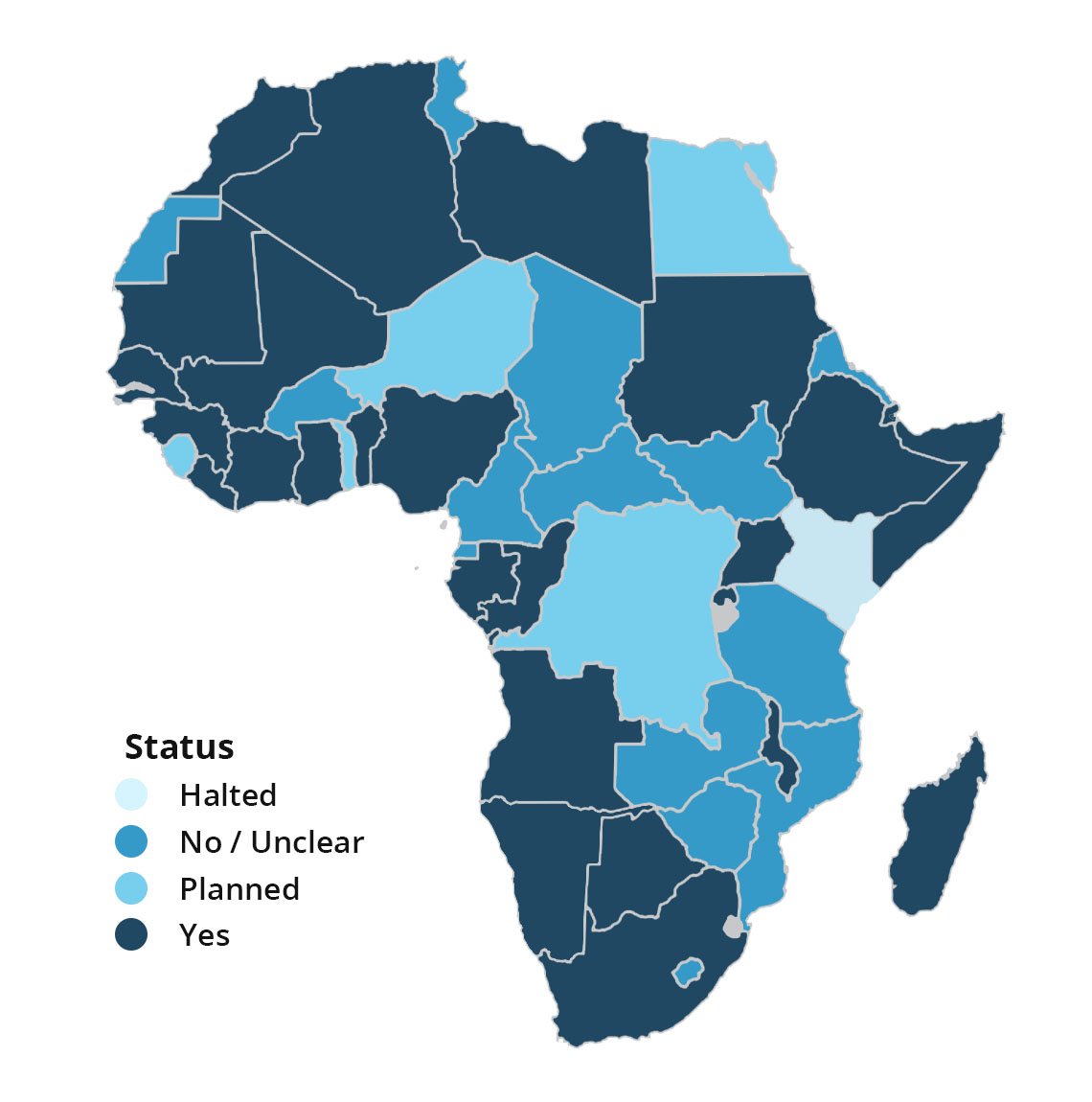

“Biometric and digital ID systems are making exponential advances across the African continent, with many nations in the process of registering their populations’ biometrics into centralized national databases.”African societies are about to face an unprecedented transformation powered by the integration of AI and data-optimization technologies into politics, daily life, and elections. Biometric and digital ID systems are making exponential advances across the African continent, with many nations in the process of registering their populations’ biometrics into centralized national databases (see Figure 1). Since the spring of 2019, nearly 40 million Kenyans had their fingerprints and faces scanned by a new biometric ID system that will play a crucial role in the upcoming 2022 election. Other converging technologies—from facial and affect recognition to surveillance tools for monitoring social media content—are increasingly used by authorities to monitor populations’ behaviors and to classify minority subgroups according to “normal” and “abnormal” patterns. For instance, in February 2019, the French company Gemalto announced a smart-policing collaboration with the Uganda Police Force to deploy portable biometric devices that use AI to confirm a match on the spot. In Johannesburg, the AI software iSentry is programmed to detect “abnormal behavior” in public space, showing the risk of automated forms of predictive policing. These are just a few examples of how converging technologies are making populations’ bodies and minds increasingly traceable in real-time.

When studying the impact of information disorders on elections, we tend to seriously underestimate how converging technologies are increasingly designed to anticipate and nudge human attitudes and behaviors, with the drastic potential to manipulate and restrict political agency. The convergence of AI with pervasive facial, biometrics, and affect recognition essentially allows new forms of political, social, and behavioral engineering.

Converging technologies monitor and analyze individuals’ biometrics and behavioral data, gradually imposing social and political control over those individuals’ lives. Such “power over life” resonates with what Michel Foucault termed biopower: “[A] power that exerts a positive influence on life, that endeavors to administer, optimize, and multiply it, subjecting it to precise controls and comprehensive regulations.”3Rachel Adams, “Michel Foucault: Biopolitics and Biopower,” Critical Legal Thinking, May 10, 2017. In an era of technological convergence, algorithms essentially amplify biopower, augmenting technologies’ potential to regulate societies’ collective body.

“These actors’ collusive practices thrive in societies where data and technological governance suffers from a lack of robust regulatory and oversight mechanisms.”In several countries in Africa, these new forms of political and social controls are born out of the complex alliance between a host of actors, from foreign tech-leading nations, domestic ruling elites, to Western corporations that prosper in the data-analytics and political consultancy business. These actors’ collusive practices thrive in societies where data and technological governance suffers from a lack of robust regulatory and oversight mechanisms. A dearth of normative capacity-building and meaningful accountability has left populations and civil society organizations in several African countries vulnerable to dynamics of power-, data- and resource-capture.

Africa’s geostrategic importance in a multipolar competition

When foreign countries or corporations engage in spreading information disorders in far-away fragile nations, they are often incentivized by a long-term agenda of power and resource capture. This is obvious in African countries where foreign companies collude with political and economic elites for the shaping of electoral outcomes. These foreign companies are promised access to growing markets and varied resources—genetic and biodiversity data and rare earth minerals, metals, and oil.

For years and in a dozen African countries, lobbyists and data-brokers, like the SCL Group, have been analyzing data about African populations, from health, nutrition, sanitation, and weapons to militarized youth. These political consultancy firms are part of what I call the “global supply chains of surveillance.” And the sensitive datasets they collect give them and other companies to whom the data is auctioned off more influence in the current race for strategic positioning in Africa.

Due to the lack of accountability and capacity-building and the region’s wealth in resources and data, as well as location, international tech companies have started putting down roots in the region. We are currently witnessing a race between US and Chinese technological platforms to build data centers and information infrastructures on strategic territories—coastal cities and resource-hotspots—in the region. In the near-future, North America, with US Palantir, Cisco, and IBM at the forefront, will represent more than 30 percent of the overall biometrics industry share by 2024. But US providers are in competition with China’s Laxton Group, which has deployed nationwide biometrics and ID systems for elections in Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, Guinea-Bissau, and South Africa.

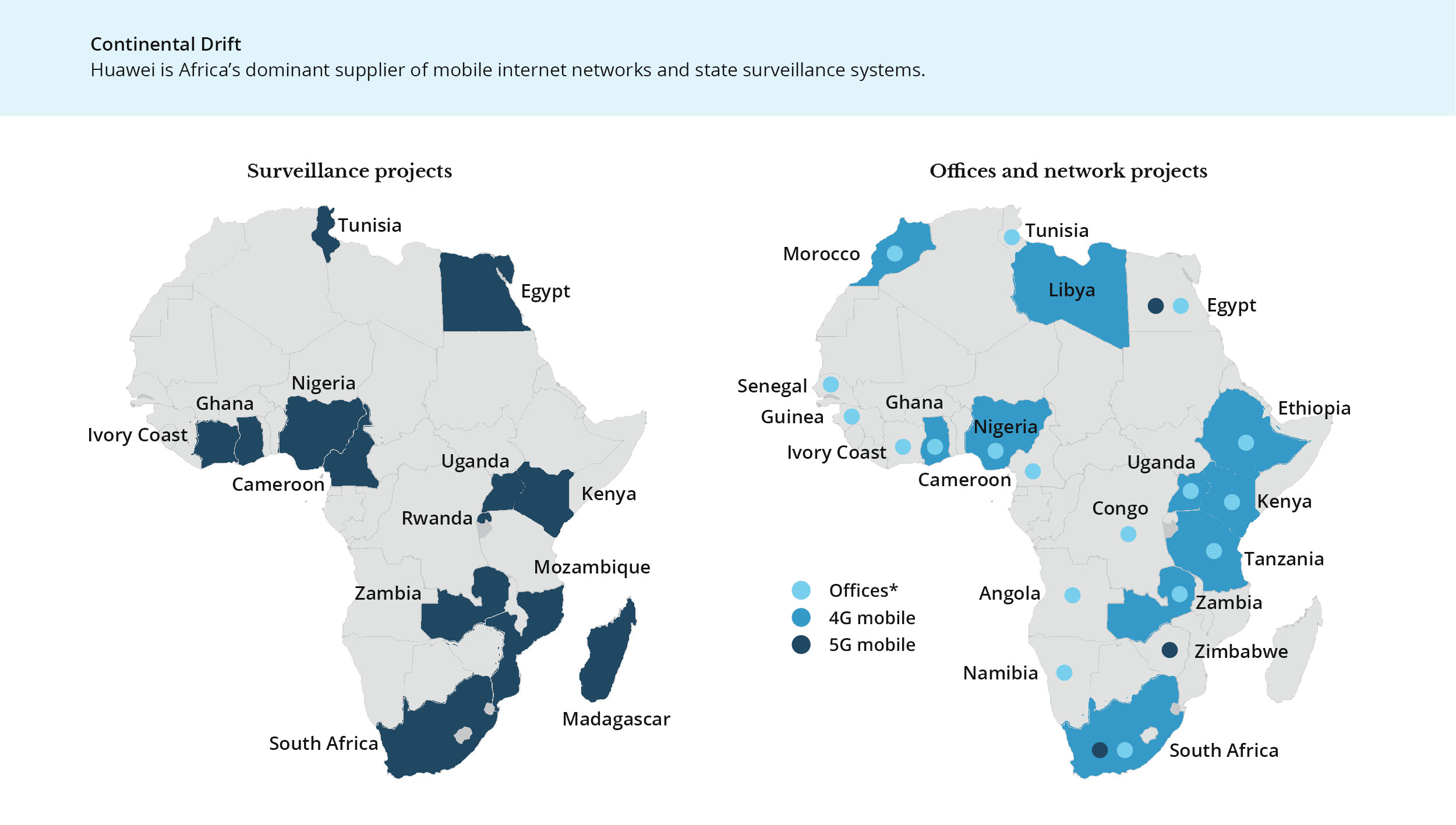

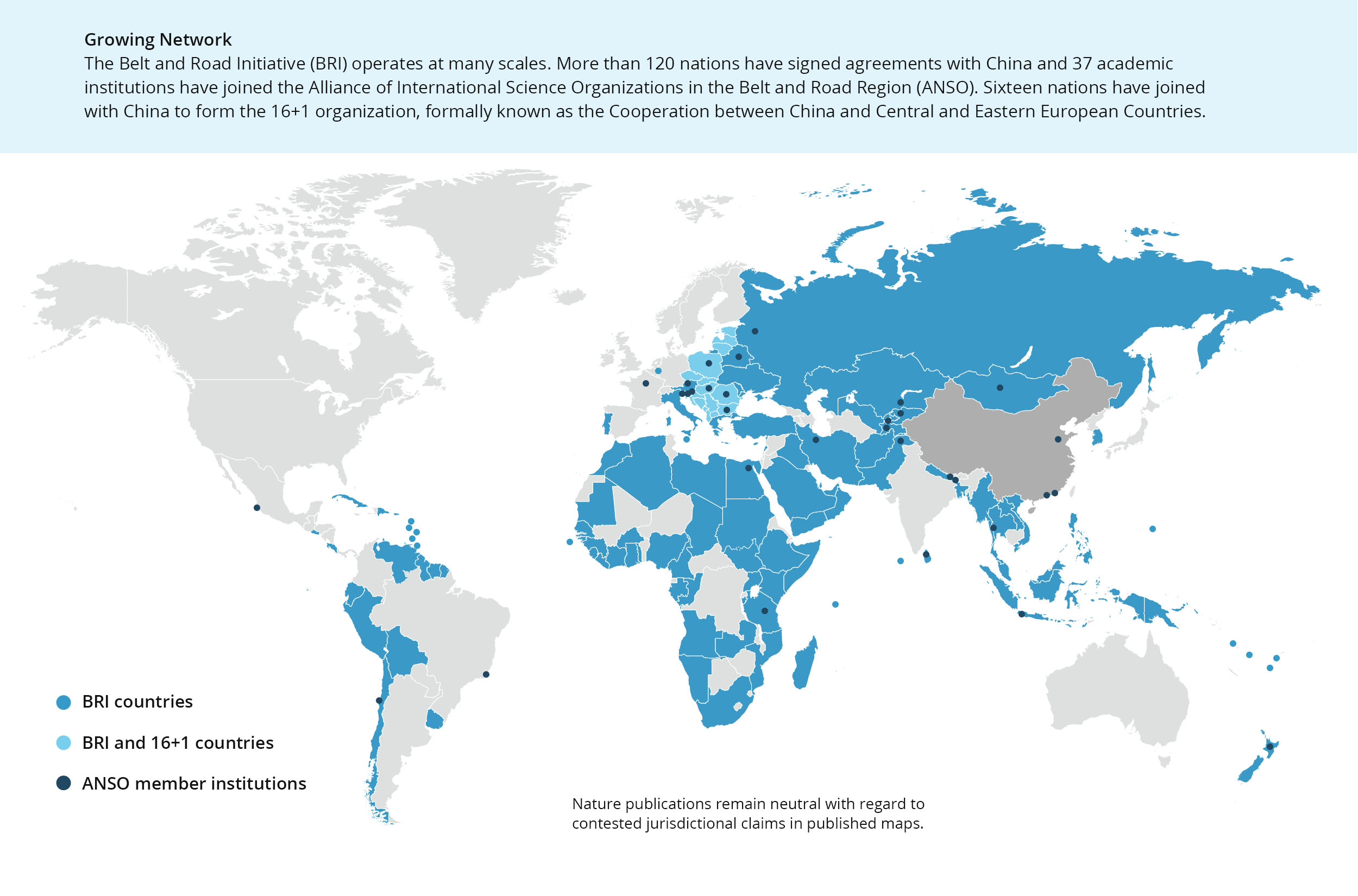

Algorithmic surveillance has become quite a lucrative business, particularly for China, which provides AI technologies in more than 55 countries with about half of them participating in loan programs under China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)4The BRI is a global infrastructure strategy promulgated by the Chinese government that aims to extend China’s geopolitical influence through the construction of roads (belt) and maintaining access to sea routes (road). (see Figures 2, 3, and 4). In February 2019, Huawei launched its first data center in Egypt, which conveniently borders the corridor that connects East Africa to Europe. The Chinese telecom also signed a contract with the Algerian government to build a data center for its custom and border authority. With BRI agreements signed with Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Egypt, China has a footprint in the Mediterranean.

“These countries constitute different geostrategic territorial corridors where future 5G digital architectures as well as cloud-computing and satellite data centers can be built.”Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa represent another El Dorado of growing digital markets, with access and control over large populations’ data, as well as energy and mineral resources needed to power the digital economy. Furthermore, these countries constitute different geostrategic territorial corridors where future 5G digital architectures as well as cloud-computing and satellite data centers can be built. Within a context of rising multipolar competition, governments in Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa will determine which cyber-governance model is going to help them secure relative economic growth and autonomy without endangering regime stability. China’s cyber-sovereignty model, which applies cyber-surveillance to preserve regime legitimacy and prevent external threats, emerges as a potential option.

Election interference in African countries

There is a wider geopolitical story behind the instrumentalization of information disorders in elections across Africa. Increasingly, national elections can be influenced to define what model of cyber-sovereignty will prevail on the world’ stage. Once, primarily, a strategic moment in a country’s national political process, each election now provides foreign, tech-leading nations with an opportunity to shape technological and data-governance models, and to play a role in the global historic definition of cyberspace.

In Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa, 2019 witnessed nascent normative efforts around privacy and data-protection. What is at stake is a competition between the values of liberal democracies with new forms of digital authoritarianism. Interestingly, the question of data protection radiates back into the international arena because, in the global digital economy, population data flow across borders.

A rising concern for policymakers, diplomats, and CEOs with global reach is the risk of facing increasingly competing visions of governance and a balkanization of cyberspace with diverging standards on privacy, security, free speech, and cross-border data-transfers. As data protection laws emerge in countries in Africa, governments might impose tighter national control of the internet, for instance by adopting China’s data-localization principles, requesting data to be stored in the country of origin.

Regulatory moves toward data-localization and cyber-sovereignty would make it increasingly difficult for the United Nations and its agencies (like the World Health Organization) to rely on global data-sharing to address shared problems such as mitigating the consequences of pandemics. This is another complex governance problem, which the United Nations will have to address if the institution wants to stay relevant when it comes to crisis prevention and global development.

The UN and the future of multilateralism

In the absence of adequate laws, policies, and corporate practices that are grounded in internationally recognized principles for human rights, the most intimate data we share can be used to undermine democratic processes and hurt citizens, in particular, the most vulnerable among us. How can UN agencies gather member states’ support to prevent the rising forms of political data-collection and manipulation that impact populations through information disorders and electoral disruptions?

“In 2020, 24 African countries out of 53 are in the process of adopting or updating laws and regulations to protect citizens’ personal data.”In 2020, 24 African countries out of 53 are in the process of adopting or updating laws and regulations to protect citizens’ personal data.5Privacy International, “2020 is a Crucial Year to Fight for Data Protection in Africa,” Privacy International, March 3, 2020. This is where the African Union (AU) and the UN could play a unique role in normative leadership, which is sorely needed at the international level: (1) support to negotiate adequate normative frameworks for populations’ data-protection, privacy, and digital rights; (2) normative foresight to better implement data-protection mechanisms, which are tailored to African countries’ challenges; and (3) the development of strategic monitoring and crisis planning capacity for electoral management bodies to help mitigate the impact of information disorders in elections and the risks of their own data manipulation.

Still the risk exists that, in the near-future, tech-leading nations and their corporate partners will increasingly instrumentalize the UN mandate in normative and technical capacity-building to crystallize their competitive advantage (through standards and proprietary technologies) and augment their control over transnational cyberspace infrastructures.

Multipolar competition is also about amplifying spheres of normative influence through discursive power and the cyber-stories we tell. The UN will not be immune to attempts at using soft discursive power and information disorders to weaken the traditional values and norms of multilateralism. This era of disinformation strongly affects trust in the multilateral order and in the UN’s leadership in protecting global populations, not only from technological and biological threats, but also from surveillance, digital, and epistemic manipulation. For the UN, the only way ahead to preserve its relevance is to provide forward-looking and robust normative leadership, partnering with the next generation of civil society and private sector actors to empower populations across the world.

Visionary normative leadership is needed.

Banner image: Government of South Africa/Flickr.

References:

→Privacy International, “Further Questions on Cambridge Analytica’s Involvement in the 2017 Kenyan Elections and Privacy International’s Investigations,’’ Privacy International, March 27, 2018.

→Robert Muthuri et al., Biometric Technology, Elections, and Privacy: Investigating Privacy Implications of Biometric Voter Registration in Kenya’s 2017 Election Process (Nairobi: Centre for Intellectual Property and Information Technology Law, Strathmore University, 2018).

→Nanjala Nyabola, “Texts, Lies, and Videotape,” Foreign Policy, August 1, 2017.