The reasons why inequality has recently made its way to the center of attention in political debate and academic research seem obvious. A new “Gilded Age” of growing inequality where the 1 percent accumulate wealth at an almost unprecedented scale seems reason enough.

Perhaps, but the overall picture is complex: there are also signs that the movement in distribution of incomes since 2008—more or less when attention to inequality resurfaced—may have been a (very) modest reversal of the growing inequality in incomes since the onset of the financial crisis. More striking to me is how, through the lens of the 1 percent, inequalities of income have become the dominant yardstick for discussing other facets of injustice, so that gender and racial inequalities are considered almost exclusively through pay gaps.

“Why has the debate on inequality come to the fore now, and why in such terms?”One side effect of the dominance of the income perspective is a narrowing of our causal horizon to look solely at personal attributes and their relation to the potential for income mobility, contributing to what Ulrich Beck called the “individualization” of modern societies, where institutions (including those producing knowledge about inequality) recast social processes of exploitation and exclusion as the result of individual choices and trajectories.1→ Beck, Ulrich. “Beyond Class and Nation: Reframing Social Inequalities in a Globalizing World.” British Journal of Sociology 58, no. 4 (2007): 679–705.

→ On the “individualization” of measures of inequality, see O’Connor, Alice. Poverty Knowledge: Social Science, Social Policy, and the Poor in Twentieth-Century US History. Princeton University Press, 2002.

In short, we seem to be starting from the effect, rather than searching for causes: income disparities are often the last step in a chain of unequal opportunities and outcomes.2 University of California Press, 1999.More info → For social scientists who trace their genealogy to Weber and Marx, this is, to say the least, exasperating. The discipline of history is no exception: there the conversation on inequality has benefited from, but been largely limited to, the efforts of historians—Angus Maddison or Robert Allen, for instance—who have used the tools of economic measurement to reconstruct income distribution over time. Like in other social sciences, other approaches to understanding past inequality, such as those inspired by the Charles Tilly, have not grasped an audience beyond academia. Yet, the historian’s approach also asks us to reflect on the conditions and genealogy of our own ways of knowing, and leads us to two questions. Why has the debate on inequality come to the fore now, and why in such terms?

University of California Press, 1999.More info → For social scientists who trace their genealogy to Weber and Marx, this is, to say the least, exasperating. The discipline of history is no exception: there the conversation on inequality has benefited from, but been largely limited to, the efforts of historians—Angus Maddison or Robert Allen, for instance—who have used the tools of economic measurement to reconstruct income distribution over time. Like in other social sciences, other approaches to understanding past inequality, such as those inspired by the Charles Tilly, have not grasped an audience beyond academia. Yet, the historian’s approach also asks us to reflect on the conditions and genealogy of our own ways of knowing, and leads us to two questions. Why has the debate on inequality come to the fore now, and why in such terms?

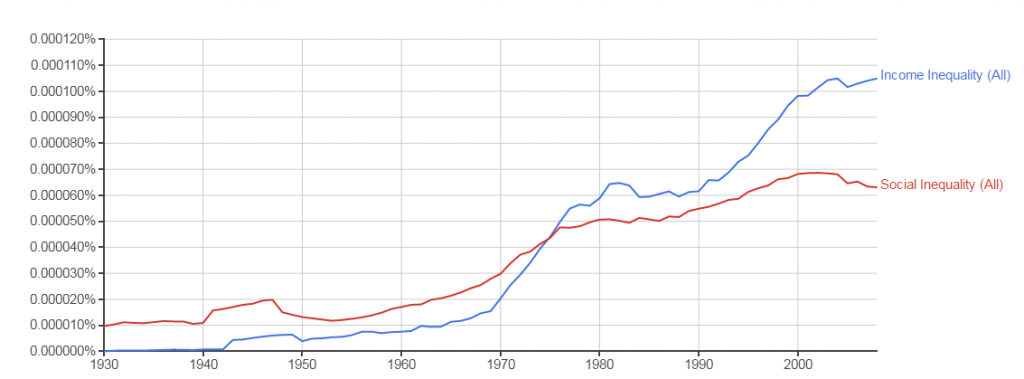

Google Books Ngram charts are a blunt tool, but can reveal some trends. Comparing the relative frequency of the terms “social inequality” and “income inequality” between 1930 and 2008, we see that while both are increasingly in use from 1970 onwards at more or less the same rate, from the early 1990s the use of “income inequality” became increasingly more frequent, with “social inequality” leveling off. Broadly speaking, the movement of both terms—and the frequency of the use of the term inequality on its own—mirrors Piketty’s hockey stick graph showing a rapid increase in the incomes of the wealthiest in Western countries since 1980. But this is not simply a story of citizens experiencing (and discussing) the unraveling of the historic reduction in earnings and wealth gaps that followed the Second World War. In the two decades since income inequalities began rising again in the West, there was little public debate about it. The academic “discovery” of inequality in the 1970s was not matched by a growth in public interest in inequality as such.3 Cambridge University Press, 2013.More info → Inequality, as opposed to poverty, unemployment, or even social exclusion, did not become a live political issue until after 2008, when the take-off of the wealthiest 1 percent was framed as a reflection of multiple troubles affecting the richest nations on the planet. This lag merits a reflection, as does explaining why a thick (admittedly excellent) tome of economic history—Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century—became a surprise bestseller. The recent history of the social and economic disciplines, and their role in shaping public debate, reveals how particular “ways of knowing” inequality have influenced the terms of the argument.

Cambridge University Press, 2013.More info → Inequality, as opposed to poverty, unemployment, or even social exclusion, did not become a live political issue until after 2008, when the take-off of the wealthiest 1 percent was framed as a reflection of multiple troubles affecting the richest nations on the planet. This lag merits a reflection, as does explaining why a thick (admittedly excellent) tome of economic history—Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century—became a surprise bestseller. The recent history of the social and economic disciplines, and their role in shaping public debate, reveals how particular “ways of knowing” inequality have influenced the terms of the argument.

A Google Ngram chart tracking the use of “income inequality” and “social inequality” between 1930 and 2008. Access this data through the Ngram Viewer here.

The middle of the twentieth century—decades that also saw the growing professionalization and entrenchment of the social sciences in universities and government agencies—saw little focused attention on the issue of income inequality. The growth in academic interest on the topic in the 1970s can be traced back to the development of national income accounting, and the gradual construction of historical and international data series based on its conventions. The first part of this story is about the measurement of between-country inequalities. The creation of statistical abstractions allowing comparisons of production and national wealth in industrialized nations by economists such as Simon Kuznets was built on by others such as Colin Clark to produce data on the GDP of nations across the world. Despite the objections of Kuznets himself, who, amongst others, argued economic measurement had to take into account the historical and social specificity of each site, these ways of seeing (and creating) the economy were rapidly diffused.

“This vision of inequality was a double-edged sword.”The emerging field of development economics and its international infrastructure, from the World Bank to the United Nations, found in GDP estimates a system of comparison and abstraction that made their global remit manageable. And, for newly independent postcolonial nations, they offered a means to comprehend and modernize the nation. Whether the “household” was the most appropriate unit of analysis everywhere, the degree of monetization of different forms of production and exchange, the complexities of each national context were lost in the universalizing flattening of GDP calculations. The development of the concept of a global economy and of the possibility of comparison revealed, in Speich’s words, “a sensational new view of the world as a place of enormous poverty,” and of vast inequalities between nations.4 Speich, Daniel. “The Use of Global Abstractions: National Income Accounting in the Period of Imperial Decline,” Journal of Global History 6, no. 1 (2011): 7–28.

This vision of inequality was a double-edged sword. If on one hand it constrained an understanding of a diverse and complex world within a Western-derived productivist and ostensibly depoliticized model; on the other it also helped represent an exploited “Third World,” producing stylized facts that could be used to mobilize anticolonial and postcolonial nationalist movements.5 See, for example:

→ Alacevich, Michele. “The World Bank and the Politics of Productivity: The Debate on Economic Growth, Poverty, and Living Standards in the 1950s.” Journal of Global History 6, no. 1 (2011): 53–74.

→ Bonnecase, Vincent. “Inequality in the World: The Emergence of a Political Idea in the 20th Century.” In Genevey, Rémi, R. K. Pachauri, and Laurence Tubiana (eds.) Reducing Inequalities: A Sustainable Development Challenge (TERI, 2013).

→ Konkel, Rob. “The Monetization of Global Poverty: The Concept of Poverty in World Bank History, 1944–90.” Journal of Global History 9, no. 2 (2014): 276–300. Over time it encouraged international organizations to chart and incorporate distributional issues into their agendas. Under the presidency of Robert McNamara (1968–1981), the World Bank made poverty alleviation (and measurement) a core concern. This policy shift took place in the context of the search for a new mode of influence in a post-oil-shock and postcolonial world order, and by McNamara’s own encounters with poverty alleviation as a security policy in Vietnam, with Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, and, further back, with the ideas that guided the Marshall Plan.6 Brookings Institute Press, 2011.More info → Even if the centrality of poverty and distribution within the World Bank waned during the heyday of structural adjustment agendas in the 1980s, the Bank continued to be a key producer of statistical knowledge on global distribution of incomes, particularly after 2000. Many, if not most, of the current leading authors in the field have long connections to the Bank: François Bourguignon, Branko Milanovic, or Martin Ravallion.

Brookings Institute Press, 2011.More info → Even if the centrality of poverty and distribution within the World Bank waned during the heyday of structural adjustment agendas in the 1980s, the Bank continued to be a key producer of statistical knowledge on global distribution of incomes, particularly after 2000. Many, if not most, of the current leading authors in the field have long connections to the Bank: François Bourguignon, Branko Milanovic, or Martin Ravallion.

The attention paid to inequalities of income within Western industrial nations followed a somewhat different trajectory. The postwar Western experience helped keep inequality as an issue that pertained primarily to the “Third World.” As the reconstruction of patterns of distribution pioneered by Atkinson, Saez, and Piketty have shown, the incomes of wealthy elites of the prewar era were decimated by wartime inflation and political change, leading to a relative equalization of wealth, sometimes called the “Great Compression.”7 Goldin, Claudia, and Robert A. Margo. “The Great Compression: The Wage Structure in the United States at Mid-Century.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 107, no. 1 (1992): 1–34. This was accompanied by a dramatic qualitative transformation of standards of living for the majority of the population. As such, and in contrast to later developments, it is natural that the decades between the end of the war and the transformation of the mid-1970s would be seen as an age of equality.

But a closer look shows that social-democratic egalitarianism was only one strand amongst others that combined in a variety of ways across nations (and sometimes rather weakly) to produce different modes of organizing society and distributing income and opportunity that varied substantially in their aim and effect in reducing inequality. Other goals, such education-driven productivity gains, the reestablishment of a patriarchal order, the stimulation of consumption, or a religion-inspired war on squalor were in play. Reducing inequality per se was not necessarily at the forefront of political and social projects in the postwar era; rather, it was the growing affluence of the postwar era put the question of distribution on hold.

“Inequality and poverty are distinct issues, but the focus on measures of absolute poverty had the side effect of making inequality less visible.”“[F]ew things are more evident in modern social history than the decline of interest in inequality as an economic issue,” asserted J. K. Galbraith in 1958; “inequality has ceased to preoccupy men’s minds.” For the author of The Affluent Society, the key reason was simple: “increased production is an alternative to redistribution.”8 London: Hamish Hamilton, 1969.More info → This lack of concern was reflected in the little systematic and sustained interest in constructing measures that spanned the entire population and permitted painting a picture of distribution: in 1960s Britain, the sociologist and poverty campaigner Peter Townsend lamented the exclusive focus of welfare measurement on absolute rather than relative indicators of poverty, but it would be many years before these were produced regularly.9Townsend, Peter. “The Meaning of Poverty.” British Journal of Sociology 13, no. 1 (2010): 85–102. Inequality and poverty are distinct issues, but the focus on measures of absolute poverty had the side effect of making inequality less visible. For their part, the concern of labor economists and policymakers with productivity led them to focus on income shares and productivity of different categories of workers, making it difficult to picture inequality as a whole, its impact through paid and unpaid forms of work, as well as hiding fluctuations in the income shares of the richest, and of the poorest.10 Hirschman, Daniel. “Rediscovering the 1%: Economic Expertise and Inequality Knowledge”, Unpublished Manuscript (2014).

London: Hamish Hamilton, 1969.More info → This lack of concern was reflected in the little systematic and sustained interest in constructing measures that spanned the entire population and permitted painting a picture of distribution: in 1960s Britain, the sociologist and poverty campaigner Peter Townsend lamented the exclusive focus of welfare measurement on absolute rather than relative indicators of poverty, but it would be many years before these were produced regularly.9Townsend, Peter. “The Meaning of Poverty.” British Journal of Sociology 13, no. 1 (2010): 85–102. Inequality and poverty are distinct issues, but the focus on measures of absolute poverty had the side effect of making inequality less visible. For their part, the concern of labor economists and policymakers with productivity led them to focus on income shares and productivity of different categories of workers, making it difficult to picture inequality as a whole, its impact through paid and unpaid forms of work, as well as hiding fluctuations in the income shares of the richest, and of the poorest.10 Hirschman, Daniel. “Rediscovering the 1%: Economic Expertise and Inequality Knowledge”, Unpublished Manuscript (2014).

Read online →

By the mid-1980s, some researchers began to notice the effect of inequality on persistent poverty despite a return of economic growth following the post-oil-crash recession, as well as the rapid takeoff of top incomes. However, as O’Connor shows, the approach to measurement and analysis used in this “rediscovery of inequality,” which focused on wage-earning males and collapsing societal factors such as race and gender into individual characteristics, did little to highlight potential systemic and structural causes of inequality.11 Princeton University Press, 2002.More info →

Princeton University Press, 2002.More info →

We can see a parallel story in Britain and in other Western nations. Atkinson was almost alone in his work on compiling and analyzing data on income and wealth inequality from the 1960s. It was not until the 1990s that the economics profession across the West began paying attention to distributional issues, in the context of GDP growth that was increasingly decoupled from wage growth for the majority of the population. The first edition of Atkinson and Bourguignon’s Handbook of Income Distribution could still say that “income distribution still remains rather peripheral in economics” and, within the discipline, “little is actually understood about the determinants of distribution.”12 Elsevier, 2000.More info → It was only around the turn of the millennium that the data produced by the efforts of Atkinson and others, particularly Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty, were met with increasing interest by academics who had, once more, discovered inequality.13 Hirschman, Daniel. “Rediscovering the 1%: Economic Expertise and Inequality Knowledge”, Unpublished Manuscript (2014).

Elsevier, 2000.More info → It was only around the turn of the millennium that the data produced by the efforts of Atkinson and others, particularly Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty, were met with increasing interest by academics who had, once more, discovered inequality.13 Hirschman, Daniel. “Rediscovering the 1%: Economic Expertise and Inequality Knowledge”, Unpublished Manuscript (2014).

Read online →

Like the Americas, inequality did not need to be “discovered” by economics to become real. Social scientists of a range of disciplines had continued to pay attention to what we could term a range of “social inequalities.” But it is symptomatic of the public weight of economics since the last quarter of the twentieth century that without the availability of the “stylized facts” of global and national income, inequality as an issue could not find a way to capture the public imagination. This is not to say that it was the “rediscovery of inequality” by economics that made it appear as a live political issue—but there is little doubt that it shaped the way in which emerging national and transnational political movements questioned the legitimacy of contemporary capitalism. Arguably, it was the global social justice movement (GSJM), and its influence on the subsequent emergence of Occupy and related social movements after 2008, that merged the perspectives of global and domestic inequalities—but it did so through the particular frame of the incomes and wealth of a global elite, the 1 percent.

“Inequality did not need to be ‘discovered’ by economics to become real.”The GSJM, which came to particular attention in the anti-WTO demonstrations in Seattle in 1999, used the issue of global income inequality as one of its central themes, albeit in the context of and in tandem with a wider perspective that highlighted social processes of gender, racial, and religious social and political discrimination, as well as economic oppression.14 Steger, Manfred B., and Erin K. Wilson. “Anti-Globalization or Alter-Globalization? Mapping the Political Ideology of the Global Justice Movement.” International Studies Quarterly 56, no. 3 (2012): 439–454.

For all its undoubted global reach, however, the GSJM was not able to gain a foothold as a domestic issue in Western polities. It took the onset of the recession caused by the 2008 financial crisis to bring the inequality frame “home.” This is particularly clear in the case of Occupy Wall Street in the United States, but also in a range of European movements, from Indignados to Nuit Debout, which drew on the GSJM’s experience of campaigning and agitating on global inequality to combine this issue with the recently available and increasingly discussed data on the rising incomes of elites.15 Routledge, 2013.More info →

Routledge, 2013.More info →

Inequality, and particularly the image of a super-rich global elite invoked by the “1 percent” tag, became a way of relating the unease of an array of diverse constituencies encompassing, amongst others, farmers threatened by global competition, middle-class university graduates, through those whose prospects were made bleak by the disappearance, through delocalization or technological change, of secure blue-collar occupations.16Calhoun, Craig. “Occupy Wall Street in Perspective.” British Journal of Sociology 64, no. 1 (2013): 26–38.

Successful though it was in the moment, the 1 percent view of inequality is also fraught with limitations. The very language and terminology of income inequality does not by itself bring clarity. Inequality is a noun, not a verb, and as such obscures the issue of agency, which further contributes to its naturalization and to conflating the many different processes through which unequal outcomes come into being. These vary tremendously in scale, from face-to-face discrimination, through the practices of organizations all the way through to the global operation of economic systems. They also vary temporally, from the rapid changes brought about by crises, through generational patterns of accumulation, all the way to the long-lasting inheritances of distant history.17 Ramos Pinto, Pedro, “Why Inequalities Matter” in Genevey, Rémi, R. K. Pachauri, and Laurence Tubiana (eds.) Reducing Inequalities: A Sustainable Development Challenge (TERI, 2013).

More info →

As such, as social scientists we find ourselves locked in a contradiction: the language and methods of economics and its forms of measurement have narrowed the ways in which we understand inequality. Yet, at the same time, using income as a common denominator of multiple dimensions of inequalities has proven to be an extremely successful heuristic. In our current project at the University of Cambridge, the Measure of Inequality: Social Knowledge in Historical Perspective, funded by the Philomathia Foundation, we are exploring some of the implications of this paradox, which will be presented at an international conference in 2017. What are the trade-offs between aggregation, abstraction, and the political “usability” of academic knowledge? Can we learn from past forms of representing inequality, which relied as much on analytical narratives as on quantification, to broaden the horizon of current debates? Or should the battle be fought on the field of more “intelligent” measures of inequality, from the Human Development Index to the proliferation of new indices and indicators as part of the “beyond GDP” agenda?18 Katherine Trebeck, “Can Alternative Economic Indicators Ever Be Any Good if They Are Devised Solely by Experts?” FP2P (blog), August 21, 2014.

Read online → And in that case, can the past reveal the processes through which particular ways of abstracting and measuring the world become established, and with what consequences?

History, that most eclectic of disciplines, does not hold any special claim to understanding inequality better than any other approach. Nor is the past the exclusive fiefdom of the historian. But history does have something important to offer: the historian’s craft, in Marc Bloch’s beautiful term, is one of bricolage—an open-ended and reflexive act that borrows, plays with, and combines the tools of production of knowledge of other disciplines. Examining its evidence, because sparse and often opaque, requires a conversation between the methods of a wide range of expertise. As such, through an engagement with the past, we sociologists, economists, anthropologists, political scientists, and others continue to find a place in which to see our approaches questioned and reflected in productive ways.

References:

→ On the “individualization” of measures of inequality, see O’Connor, Alice. Poverty Knowledge: Social Science, Social Policy, and the Poor in Twentieth-Century US History. Princeton University Press, 2002.

→ Alacevich, Michele. “The World Bank and the Politics of Productivity: The Debate on Economic Growth, Poverty, and Living Standards in the 1950s.” Journal of Global History 6, no. 1 (2011): 53–74.

→ Bonnecase, Vincent. “Inequality in the World: The Emergence of a Political Idea in the 20th Century.” In Genevey, Rémi, R. K. Pachauri, and Laurence Tubiana (eds.) Reducing Inequalities: A Sustainable Development Challenge (TERI, 2013).

→ Konkel, Rob. “The Monetization of Global Poverty: The Concept of Poverty in World Bank History, 1944–90.” Journal of Global History 9, no. 2 (2014): 276–300.

Read online →

Read online →

More info →

Read online →

Comments are closed.