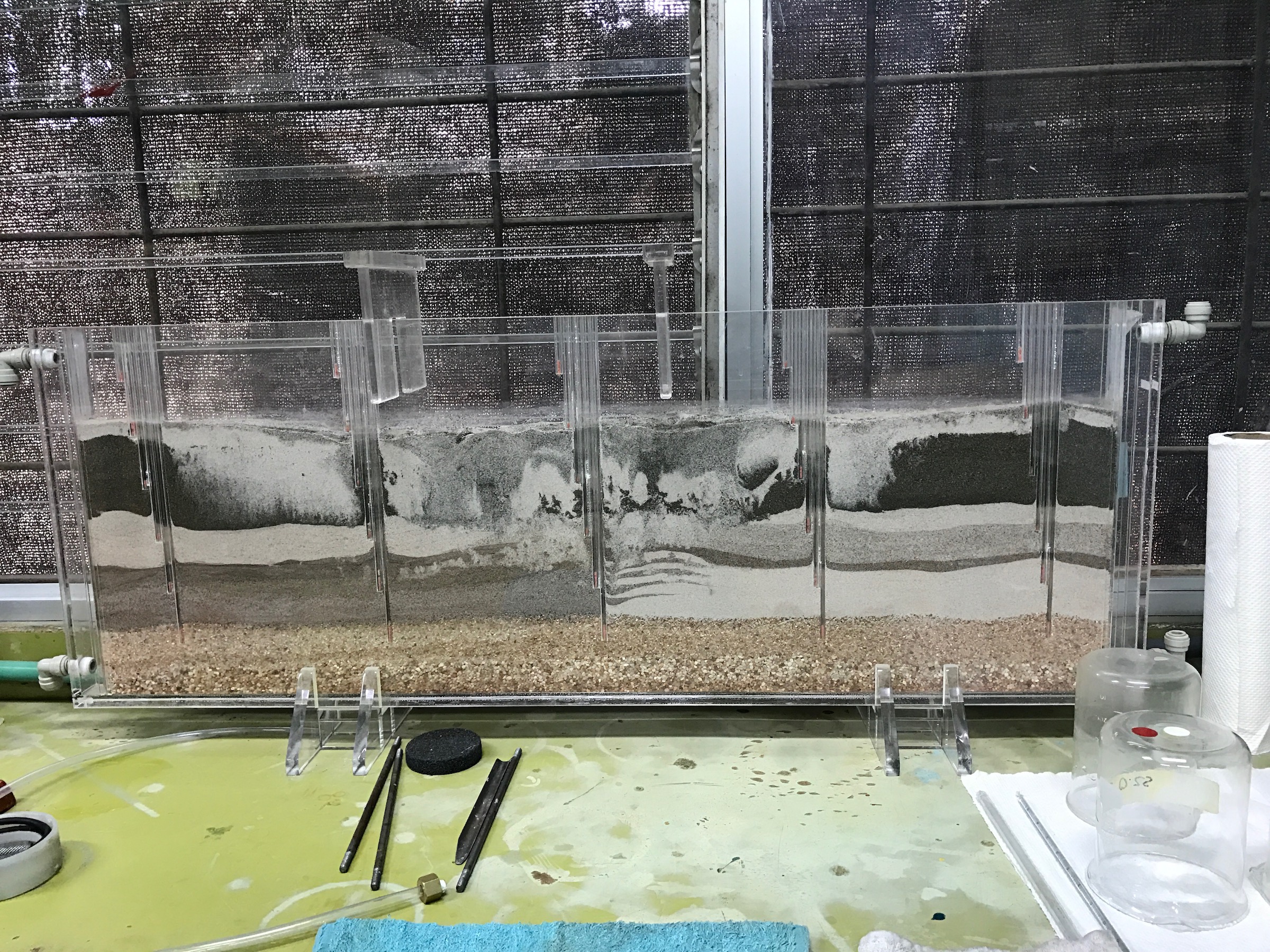

In 2017, Jorge welcomed me to the headquarters of Costa Rica’s underground water agency. His supervisor had asked him to show me “the model” at work. After many years of fieldwork on water issues, I had already been introduced to many models: the mathematical model to calculate extraction rates, two different pieces of software that model aquifer flow, the regulatory model Costa Rica’s agency follows, and sponges as a preferred physical model to conceptualize aquifers. And yet, Jorge and his supervisor referred to this one as el modelo, the model.

After walking down a zigzagging hallway, we eventually entered an office where three unused desks were stored. In this unremarkable bureaucratic context, illuminated by fluorescent lighting, the model rested atop an old desk, a temporary pedestal. The model consisted of a transparent plastic structure simulating a vertical slice of the underground that revealed its stratigraphic architecture. It resembled a skinny terrarium with layers of pulverized rock of different textures, colors, and thicknesses. A number of transparent tubes penetrated to different depths, each representing a well. Larger indentations stood for rivers and lakes, and on one side there was a deeper section that, as Jorge explained, represented the ocean.

If I am honest, after hearing from many people about this model, upon seeing it, I was a bit underwhelmed. But why was this the case? What was I expecting? Had talk about the digitalization of life, the artificiality of intelligence, or the carbonization of blame desensitized me to pulverized stone, hoses, and plastic? Nevertheless, despite my initial reaction, I was to learn about the active social life this model led. Jorge and his colleagues take it to different locations in Costa Rica. They use it at community meetings, environmental fairs, school visits, and during planning meetings with local municipal authorities. Some critics dismiss this work of visiting locations outside of the agency’s headquarters to make the model “work” as inconsequential. Others classify it as an educational effort that, at best, will have long-term effects. And yet, in its modesty, this model helps public servants reject dominant patterns of thought that reduce aquifers to mere water quantities passively waiting extraction. Through this model, aquifers become dynamic formations intimately connected to everyday lives above the surface. What can we learn from the work that Jorge and his colleagues perform by making this model work? And how might they, Jorge and the model, help us think water and stone together, and in movement?1In this “Ways of Water” series, Alexis Rider offers another way of thinking water and stone through her essay, “Keeping Time with Melting Rock.”

More than water quantities

Water and stone are archetypes of binary relations. They are conjured as opposites to each other. Water is supposed to be fluid, form changing, in constant movement. Stone is said to be fixed, enduring, and static unless intentionally moved. And yet, in aquifers, water and stone are one. Aquifers are an intimate relationship constituted by water movement depending on stone’s stability. For a long time, and in many places around the world, including Costa Rica, this intriguing relation remained the realm of specialized scientists and well-drilling companies. In the twenty-first century, however, aquifers are occupying more public attention, inspiring different ideas of sociality and solidarity, and justifying the expansion, or stoppage, of massive capitalist endeavors such as the extraction of oil, gas, and minerals. Aquifers are now central to urgent questions about the endurance of life in our planet and are at the center of financial experiments that open the door for speculation on water futures.

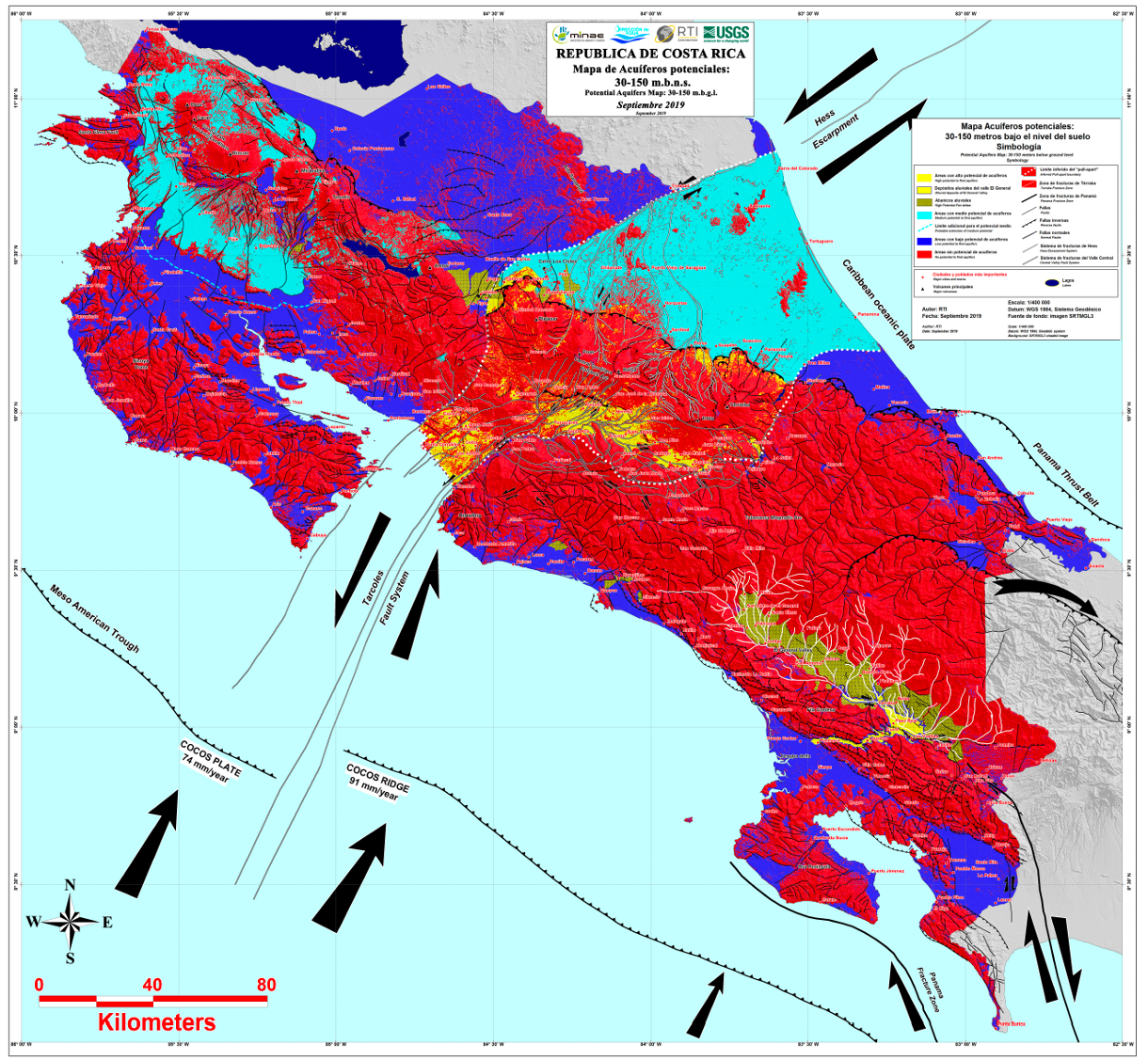

In Costa Rica, aquifers undergird 44 percent of the country’s continental territory. Today, increasing conflicts among local residents, owners of pineapple plantations, and luxury real estate developers have drawn the attention of a broad swath of the public to consider how life forms depend on groundwater. At the turn of this century, for example, a conflict known as the Sardinal case became the first local water struggle to capture national attention, revealing to the public the effects of unequal development strategies that privilege transnational tourism investments over small property owners and local residents. Subsequently, agrochemical pollution of aquifers that supply local communities, an oil spill that almost tainted permanently the aquifer that supplies water to half of the population in the capital city, and a variety of smaller environmental emergencies have put aquifers at the center of national agendas around urban development, agricultural expansion, and environmental protection. People are now aware that their constitutionally recognized human right to water depends on the health and protection of aquifers. In response to this conjuncture, during the past few years the Costa Rican government has invested substantial financial resources setting up real-time aquifer monitoring systems, producing a national aquifer map in collaboration with the US Geological Survey (USGS), and experimenting with participatory approaches for aquifer management.

These scientific and management initiatives unfold within Costa Rica’s distinct regulatory context. By law, all underground resources, including water, are owned by the state and, in principle, cannot be disposed of without some form of government authorization. This implies that, in the eyes of public officials, large and small property owners, as well as residents that are not owners, are asked to take responsibility over aquifer protection despite lacking automatic rights to access, use, or sell the groundwater underneath their land. As they try to motivate residents and owners to join aquifer protection projects, public servants, like Jorge, find themselves trying to offer new imaginaries that render the subsurface a lively, dynamic substrate. They aim to disseminate the idea that aquifers are more than containers holding water waiting to be extracted. Jorge and his model are key players in these efforts.

And yet, despite this increased attention, aquifers continue to puzzle spatial imaginaries.2Spatial imaginaries entail collectively held perceptions of geophysical elements (such as the surface and the subsurface), as well as normative ideas of responsible conduct toward those geographic formations. Spatial imaginaries are cultivated over time and circulate through different media, including images, maps, and scientific models. See Ghassan Hage, “The Spatial Imaginary of National Practices: Dwelling—Domesticating/Being—Exterminating,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 14, no. 4 (1996): 463–485; Bob Jessop, “Economic and Ecological Crises: Green New Deals and No-growth Economies,” Development 55, no. 1 (2012): 17–24; Josh Watkins, “Spatial Imaginaries Research in Geography: Synergies, Tensions, and New Directions,” Geography Compass 9, no. 9 (2015): 508–522. For example, their underground condition makes them directly inaccessible to the senses. Unlike other underground formations, such as caves and mines, aquifers cannot be inhabited.3For a discussion of aquifers as hydro-lithic choreographies that challenge the human sensorium, see Andrea Ballestero, “Aquifers (or, Hydrolithic Elemental Choreographies),” in “Theorizing the Contemporary,” Fieldsights, June 27, 2019. Our capacity to envision aquifers is mediated by all sorts of sensorial extensions: images, mathematics, stories. Perhaps because of this ontological indocility, aquifers have been historically reduced to tanks holding quantities of water. This tank-like imaginary builds on centuries of geological ideas that describe the underground as a series of lithic layers changing at temporal scales that are too slow for humans to grasp. In these stratigraphies, water recedes to the background and aquifers become exceptional formations lodged in subterranean cracks or crevasses. In geological renderings, aquifers are watery irregularities in an otherwise expansive lithic subsurface.

This idea of a subterranean world where water is exceptional and rests statically in nooks fits comfortably with the logics of capitalist industries. These logics replicate a fundamental partition between the lively—which sits above the surface of the earth—and the inert—which lies underneath.4For another two takes on this fundamental partition between life and death in late liberalism, see Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Geontologies: A Requiem to Late Liberalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016) and Kathryn Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2018). This synergy between scientific knowledge, rigid partitions between the lively and the inert, and the imperative to commodify subterranean substances enables the reproduction of a powerful extractivist paradigm that has dominated both capitalist relations with the underground and scholarly analyses of how those relations are structured. Extractivist projects of the underground aim to dislodge oil, gas, and minerals setting them in motion through above-ground international trade circuits—financial and material.5 New York: Verso Books, 2011More Info → This paradigm implicitly presumes the underground is a petrified space, a sort of vault holding potential commodities. In this petrified space, aquifers are managed as intruding disruptions to be channeled away (the case of mines), instruments to intensify extraction techniques (as in fracking projects), or obstacles for seamless extraction and accumulation (as in the construction of pipelines that threaten the relations between people, land, and groundwater as kin).

New York: Verso Books, 2011More Info → This paradigm implicitly presumes the underground is a petrified space, a sort of vault holding potential commodities. In this petrified space, aquifers are managed as intruding disruptions to be channeled away (the case of mines), instruments to intensify extraction techniques (as in fracking projects), or obstacles for seamless extraction and accumulation (as in the construction of pipelines that threaten the relations between people, land, and groundwater as kin).

Water + Stone = Movement

Back at the underground water agency, Jorge asked if I wanted to see the model working. He had prepared his implements carefully: water in a squeezable bottle, dyes of different colors, a yellowish mini hose. He grabbed his materials, began squeezing the bottle to release the water on the top layer and allow it to percolate and, at the same time, explained how he uses the model: “It is all about how you pull people in.” And just like that, he unleashed a descriptive project intended to decipher an aquifer aesthetic that embraces the liveliness of water and stone, together.

“I tell them a story,” he said. “I narrate what is happening above the ground, to remind them of what they know. I then ask questions about what is happening under the surface. I tell them, this is a water extraction pump, and it turns out there is a neighbor nearby. And his well is much deeper. So, this neighbor goes to turn his pump on, because it is noon and they are going to make lunch at his house. Like I said, you have to build a complete story so that it makes sense,” he continued while manipulating the squeezable bottle. “So, the señor is there, he arrives to the place where the pump sits and at the count of three, he starts it. And so, I pump water with this syringe. Because I have explained before that there is pollution on this side, they can see how as I pump, the water pulls the pollution plume deeper into the aquifer. And, let me tell you, this part, when they see how water comes out like this, yellow, is shocking to them.” Each time he meets his audience Jorge builds stories like this one, narrating relations between life above the earth and fluid mechanics below it. He conveys the lively push and pull of water. He zooms into the pressured contact between water and stone, refusing any quantitative shortcut to reduce aquifers to an accounting exercise and a figure of extractable water.

Jorge’s work is a modest but powerful practice of deciphering6Sylvia Winter proposes a deciphering practice to understand what meaning does, not only what it consists of. A deciphering project aims to produce an aesthetic that transgresses the distribution of life and death that dominant cultural schema, particularly in relation to Black life, have sedimented in our meaning making practices. A deciphering semiotic practice opens space for new vocabularies and political practices that reject prescribed allocations of the good and the bad, the valuable and the valueless, the disposable and the protected. Sylvia Wynter, “Rethinking ‘Aesthetics’: Notes Towards a Deciphering Practice,” in Ex-iles: Essays on Caribbean Cinema, ed. Mbye Cham (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1992), 237–279. an aquifer aesthetic that refuses the reductionism of extraction. He expertly intensifies the iconic power of his model, emphasizing how its layers, water choreographies, and lithic architecture embody the movement that happens under people’s feet as they stand in front of his demonstration (or under yours). Jorge builds this iconic effect through a series of scalar oscillations. On the one hand, the model reduces the scale of the human above the surface, minimizing its presence in relation to layers of rock and gravel that undergird the sanitation habits or water extraction practices Jorge describes with his stories. On the other hand, the model re-stages the underground by augmenting the scale of the observer. As he tells stories about the staged movement of water throughout the crushed rock, he grants his observers the power of maximized perspective. A perspective that moves volumetrically, below the surface, following the unruly form of an aquifer.

Modest techno-legal devices

In bureaucratic and regulatory spaces, such as Costa Rica’s underground water agency, models are “techno-legal devices,” improvisational spaces with the capacity of channeling long histories of ideas and sociality while also enabling the formation of new conceptual ecologies and politics.7 Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019More Info → Models such as Jorge’s help us understand the materiality of regulatory decisions while also opening possibilities for new social aesthetics and, potentially, new politics of water. The model and stories Jorge and his colleagues articulate are built on an aesthetic of the underground that is not passive or devoid of human sociality. In one story, aquifers are materials shaped by pumps, by the need to prepare lunch, and by the presence of nearby neighbors. Stories such as this one erase any partition that separates the subsurface from people’s everyday habits above the surface. Instead of effecting a semiotic closure that narrows people’s relation with aquifers to the act of extraction and its quantification, the model and Jorge’s stories expand the social world downward. They keep water + stone together, showing the simultaneity of underground water flow and the señor moving back and forth, having lunch, knowing what his neighbor is up to with water. The power of this model as a techno-legal device is less rooted in the precision of the data that go into its creation, and more on its capacity to embody a form of life. That material re-staging makes the patterns that structure life evident and potentially open for contestation. The physical model thrives in its aesthetic capacity to re-stage by playing with scalar oscillations that are fluid, both literally and metaphorically.

Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019More Info → Models such as Jorge’s help us understand the materiality of regulatory decisions while also opening possibilities for new social aesthetics and, potentially, new politics of water. The model and stories Jorge and his colleagues articulate are built on an aesthetic of the underground that is not passive or devoid of human sociality. In one story, aquifers are materials shaped by pumps, by the need to prepare lunch, and by the presence of nearby neighbors. Stories such as this one erase any partition that separates the subsurface from people’s everyday habits above the surface. Instead of effecting a semiotic closure that narrows people’s relation with aquifers to the act of extraction and its quantification, the model and Jorge’s stories expand the social world downward. They keep water + stone together, showing the simultaneity of underground water flow and the señor moving back and forth, having lunch, knowing what his neighbor is up to with water. The power of this model as a techno-legal device is less rooted in the precision of the data that go into its creation, and more on its capacity to embody a form of life. That material re-staging makes the patterns that structure life evident and potentially open for contestation. The physical model thrives in its aesthetic capacity to re-stage by playing with scalar oscillations that are fluid, both literally and metaphorically.

Despite seeming somewhat unremarkable when resting on top of a desk, as it is activated and put to “work,” Jorge’s model becomes charismatic and invites us to think of how people are pulled in to make sense of volumetric dynamics that do not replicate partitions between lively and inert, fluid and fixed, water and stone. If, as we know, descriptive practices have the power to shape the world, what might seem an inconsequential story uttered at a small environmental fair or a municipal meeting is, in fact, an opening for deciphering the world, making the ways of aquifers knowable, but also re-shaping the limits of the possible, yes by narrowing down certain options but also by opening the possibility of creating different spatial imaginariness that do not make the petrified aesthetics of extractivism inevitable. With its technical modesty, the model offers its materiality, in combination with Jorge’s stories, to inspire questions. This model and the stories that accompany it work to re-stage aquifers as lively, dynamic formations. The model and its accompanying stories expand the social world downwards, pulling water + stone upwards, without depleting their aesthetic through the logic of endless extraction.

I would like to thank Etienne Benson, Christy Spackman, Alexa Dietrich, Rodrigo Ugarte, and Robert Werth for helping streamline the text and clarify its central points.