Summary

How have heightened border controls affected the decision-making of unauthorized Mexican migrants to the United States?1Testimony prepared for the House Judiciary Committee, Field Hearing on Immigration, San Diego, Calif., August 2, 2006. My research findings, based on highly detailed, face-to-face interviews with 1,327 migrants and their relatives in Mexico during the last 18 months,2These findings are reported in detail in Wayne A. Cornelius and Jessa M. Lewis, eds., Impacts of Border Enforcement on Mexican Migration: The View from Sending Communities (Boulder, Col.: Lynne Rienner Publishers and Center for Comparative Immigration Studies, UCSD, forthcoming 2006); and Wayne A. Cornelius, David Fitzgerald, and Pedro Lewin Fischer, eds., Mexican Migration to the United States: The View from a ‘New’ Sending Community(Boulder, Col.: Lynne Rienner Publishers and Center for Comparative Immigration Studies, UCSD, forthcoming 2007). support earlier research showing that tightened border enforcement since 1993 has not stopped nor even discouraged unauthorized migrants from entering the United States. Even if apprehended, the vast majority (92-97%) keep trying until they succeed. Neither the higher probability of being apprehended by the Border Patrol, nor the sharply increased danger of clandestine entry through deserts and mountainous terrain, has discouraged potential migrants from leaving home. To evade apprehension by the Border Patrol and to reduce the risks posed by natural hazards, migrants have turned increasingly to people-smugglers (coyotes), which in turn has enabled smugglers to charge more for their services. With clandestine border crossing an increasingly expensive and risky business, U.S. border enforcement policy has unintentionally encouraged undocumented migrants to remain in the U.S. for longer periods and settle permanently in this country in much larger numbers.

Drawing on my more than three decades of fieldwork among Mexican migrants to the U.S., and a large body of research by other immigration specialists, I argue that a border enforcement-only (or border enforcement–first) approach to immigration control will only produce more of these unintended consequences while failing to construct an effective deterrent to illegal entry. If built, the new physical fortifications and virtual surveillance systems included in the immigration bills approved by Congress since last December will have no discernible effect on the overall flow of illegal migrants from Mexico. But these new layers of protection will give people-smugglers an additional pretext for raising fees; divert clandestine crossings to more remote and dangerous areas, multiplying migrant deaths that are already running at 500-1,000 per year, including undetected bodies; cause more unauthorized crossings to be made through legal ports-of-entry, using false or borrowed documents; and induce more migrants and their family members to settle permanently in this country, thereby increasing outlays for health care and education.

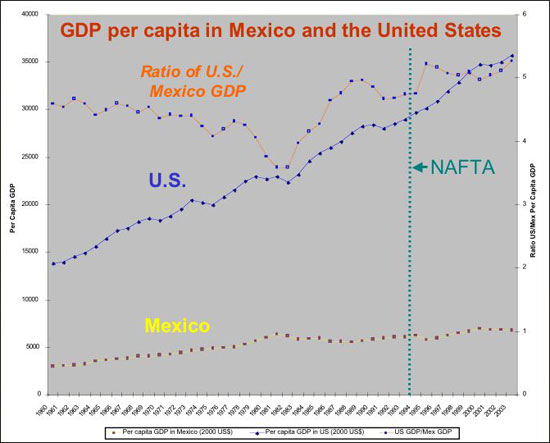

The basic problem with fortifying borders is that it does nothing to reduce the forces of supply and demand that drive illegal immigration. These forces include: (1) the U.S. economy’s persistently strong, and growing, demand for immigrant labor, at all skill levels; (2) extremely limited worksite enforcement, which has had no impact on the demand for unauthorized migrant labor; (3) the very large and still growing real-wage gap between Mexico and the United States (at least 10:1 for most low-skilled jobs); and (4) family ties – over 60 percent of the Mexican population have relatives in the U.S. – which provide a powerful incentive for family reunification on the U.S. side of the border.

More promising alternatives for reducing unauthorized immigration include a broad, earned legalization program; reducing the need to migrate illegally through significant increases in temporary and permanent visas (especially for low-skilled workers); and a binational program of targeted development to create alternatives to emigration in migrant-sending areas of Mexico.

This essay concludes with a review of the evidence concerning the economic and fiscal impacts of immigration to the United States, including immigration from Mexico, which suggests that current attempts by policymakers to limit access to immigrant labor through border enforcement are short-sighted and not in the national interest.

Specific research findings

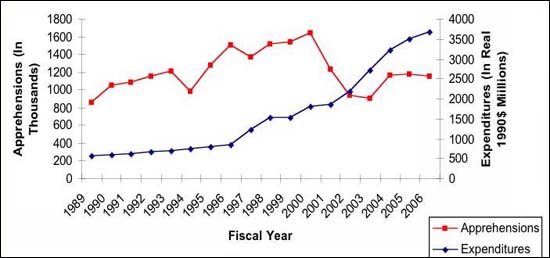

Since 1993, the U.S. Government has been seriously committed to reducing the flow of unauthorized immigration from Mexico, through tougher border enforcement. We have spent more than $20 billion on this project, and we continue to spend at a rate of more than $6 billion a year. Our strategy since 1993 has been to concentrate enforcement resources along four heavily-transited segments of the border, from San Diego in the west to the South Rio Grande Valley in the east. The logic of this “concentrated border enforcement” strategy is simple: Illegal crossings will be deterred by forcing them to be made in the remote, hazardous areas between the highly fortified segments of the border.

What effect has this strategy had on the flow and stock of illegal immigrants?

- When we embarked upon this project in 1993, the Border Patrol was making slightly less than 1 million apprehensions a year. Thirteen years later, the Border Patrol is making over 1 million apprehensions each year.

- The trends in apprehensions and spending on border enforcement intersected in Fiscal Year 2002. Since then, spending has outpaced apprehensions.

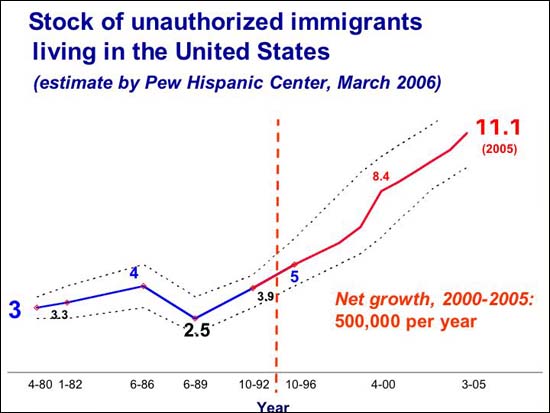

- During the period of tighter border enforcement, the population of unauthorized immigrants living in the U.S. has more than doubled in size, to something between 11-12 million.

- Illegal entries have been redistributed. Migrants and the people-smugglers who assist them have just detoured around the heavily fortified segments of the border.

When we squeezed the border in the San Diego and El Paso areas, it bulged in central Arizona. The central Arizona border was reinforced, and since last fall illegal entries have been shifting westward, to Yuma and the California border, and eastward, to New Mexico and the El Paso area. (San Diego and El Paso had been considered “operationally controlled” by the Border Patrol for the past seven years.) Most apprehensions are still occurring in central Arizona, but they are up by 21% in San Diego so far this Fiscal Year.

- The Border Patrol has reported a 45% drop in apprehensions, borderwide, in the last two months, attributing this to the President’s deployment of National Guard troops. But apprehensions have fallen by only 2% for the whole Fiscal Year to date, and that could easily turn into an increase for the year if there is a spike in apprehensions during the last three months of the Fiscal Year.

- There is no hard evidence to support linking the recent downturn in apprehensions to the presence of National Guard troops on the border. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the main effect of the deployment has been to drive more migrants into the arms of people-smugglers and enable the smugglers to raise their fees – by $500-1,000 along some segments of the border.

- Our data shows that a higher percentage of unauthorized migrants are being apprehended on a given trip to the border than in the 1980s. Even so, only about one-third are apprehended.

- And even if migrants are caught, they keep trying until they succeed. Our interviews with returned migrants in three different Mexican states revealed that between 92-97% of them eventually succeeded, on the same trip to the border.

- If the current U.S. border enforcement strategy were working, we should be seeing that the increased costs and risks of clandestine entry are discouraging prospective migrants even from leaving home. In fact, in our research in Mexican sending communities we have found that three-quarters of would-be migrants are quite knowledgeable about U.S. border enforcement operations.

- About two-thirds believe that it is much more difficult to evade the Border Patrol now than it used to be.

- Eight out of 10 believe that it is much more dangerous to cross the border without papers today, and many of the migrants whom we interviewed personally knew someone who had died trying to enter clandestinely.

- More than two-thirds had seen or heard PSAs warning of the dangers of clandestine border crossings, but fewer than one out of ten said that such messages would have any effect on their plans to migrate.

- It is difficult to overestimate the determination of the people who are willing to take such risks. One of our recent interviewees, a 28-year-old father, told us: “We don’t care if we have to walk eight days, fifteen days—it doesn’t matter the danger we put ourselves in. If and when we cross alive, we will have a job to give our families the best.”

To summarize, this is what we can say about the consequences of our 13-year experiment with tougher border enforcement:

- Most would-be migrants have become well-informed about the difficulty and hazards of clandestine entry.

- Such knowledge has no effect on the propensity to migrate.

- Unauthorized migrants are willing to take greater risks and pay much more to people-smugglers to reduce risk and gain entry.

- Despite the border build-up, most unauthorized migrants still succeed in entering on the first or second try.

- Migrants’ strategies of border crossing have been affected by enhanced enforcement (crossing points have changed; use of smugglers has increased), but illegal entry attempts are not being deterred.

The unintended consequences of the post-1993 border enforcement effort have been more important than the intended ones. The key unintended consequences include:

- Creating new opportunities for people-smugglers. Stronger enforcement on the U.S.-Mexico border has been a bonanza for the people-smuggling industry. It has made smugglers essential to a safe and successful crossing. Our research in rural Mexico shows that more than 9 out of 10 unauthorized migrants now hire smugglers to get them across the border. And the fees that smugglers can charge have tripled since 1993. By January 2006 the going rate for Mexicans was between $2,000-3,000 per head. But even at these prices it is still economically rational for migrants – and often, their relatives living in the U.S. – to dig deeper into their savings and go deeper into debt to finance illegal entry.

- Making the southwestern border more lethal. By forcing migrants to attempt entry in extremely hazardous mountain and desert areas, rather than the relatively safe urban corridors traditionally used, the concentrated border enforcement strategy has contributed directly to a ten-fold increase in migrant fatalities since 1995. A new record of 516 fatalities was set last year, and the real death toll could easily have been twice that many, because we only know about bodies that have been discovered. Since 1995, more than 4,045 migrants have perished from dehydration in the deserts, hypothermia in mountainous areas, and drowning in the irrigation canals that parallel the border in California and Arizona.

- Promoting permanent settlement in the U.S. We have succeeded in bottling up within the U.S. millions of Mexican migrants who would otherwise have continued to come and go across the border, as their parents and grandparents had done. Given the high costs and physical risks of illegal entry today, they have a strong incentive to extend their stays in the U.S.; and they longer they stay, the more probable it is that they will settle permanently.

Additional investment of taxpayer dollars in a border enforcement-centered strategy of immigration control is likely only to produce more of the same unintended consequences — not to construct an effective deterrent to illegal migration.

It could be argued that partial fortification of borders fails because of its incompleteness. If the probability of apprehension is not uniformly high, migrants will continue to cross in areas where the risk of detection is still relatively low. But complete militarization of the U.S. land border with Mexico – a sea-to-sea system of physical barriers and electronic surveillance – inevitably would push people-smuggling operations into the Gulf of Mexico and up the Pacific Coast, as well as to the U.S.-Canadian border. Mexicans could fly, visa-free, to Vancouver or any other Canadian city in close proximity the United States and seek to be smuggled across our northern border.

Securing our maritime borders would be hugely difficult, as the European Union has discovered in recent years. This year alone, more than 25,000 economic migrants from sub-Saharan Africa have braved perilous seas to try to enter the E.U. via Spain’s Canary Islands – this despite the world’s most elaborate electronic border-surveillance system. Thousands more have landed on the coasts of Italy, Malta, and Greece.

Is there a better way? I have three main recommendations:

First, we should legalize as many as possible of the unauthorized immigrants already here. That will reduce their vulnerability to exploitation, improve their mobility within the labor market, increase their contributions to tax revenues, and, by increasing family incomes, reduce high school drop-out rates and boost college-going rates among children of unauthorized immigrants.

Second, we need to reduce the necessity to migrate to the U.S. illegally. That means providing a temporary-worker option for as many as possible of prospective migrants who do not wish to remain in the U.S. permanently, and substantially increasing the number of employment-based, permanent-resident visas that we issue, especially to low-skilled workers. Much of today’s unauthorized immigration is manufactured illegality: It is a direct function of a set of immigration laws and policies that unduly restrict the number of legal-entry opportunities for foreign workers based on their occupations. Currently, only 140,000 employment-based visas are available to people of all nationalities each year. And of those, only 5,000-10,000 go to low-skilled workers. Last year, only 3,200 employment-based visas were issued to Mexicans, in a year when more than 400,000 Mexicans were added to the U.S. work force through illegal immigration.

Third, we need to help create alternatives to emigration for a larger number of potential migrants in Mexico. Narrowing the U.S.-Mexico wage gap will be a multi-decade project. Only when the Mexican labor force ceases to grow, sometime after 2015, will there be upward pressure on wages in Mexico. Apart from changing demographics, narrowing the income gap will require deeper economic reforms in Mexico: improving the tax effort, modernizing labor laws, opening up the state-run energy and electricity sectors to private investment, and so forth.

NAFTA was supposed to have reduced the U.S.-Mexico income gap, but has had the opposite effect. Per capita GDP has risen in Mexico, but it has risen much faster in the U.S. Today, annual per capita GDP in the U.S. is more than 6 times that of Mexico. NAFTA created jobs in Mexico’s manufactured-export sector, but competition from cheaper U.S. imports has put millions of small farmers out of work, and the non-agricultural jobs that have been created do not pay enough to enable most Mexican families to lift themselves out of poverty. It is the real wage difference, more than anything else, that drives migration to the United States.

In our research in rural Mexico, we have found consistently that the leading motive for migration is higher wages in the United States than in Mexico. Only 4-5% of migrants interviewed in most studies reported that they were openly unemployed before going to the U.S. In our fieldwork earlier this year, we found that only 1% had been unemployed before migrating for the first time.

Micro-development programs, targeted at the areas that send most migrants to the U.S., have the capacity to create better-quality jobs, in the places where they are needed to discourage emigration. I am referring to programs to support small-business development; to create new a financial services infrastructure that facilitates saving and reinvestment of money remitted by Mexicans working in the United States; and programs to expand physical infrastructure – roads, telecommunications, irrigation facilities, and so forth.

The U.S. is no longer in the business of “Marshall Plans.” But a creatively designed and binationally financed program of targeted development, perhaps administered by the World Bank or the Inter-American Development Bank, is an idea that deserves much more serious consideration. This is the kind of development assistance that the northern EU nations channeled in massive amounts to Spain, Greece, and Portugal, before and after these countries joined the European Union. It made possible a step-level increase in GDP growth in these countries, reduced the north-south wage differential by half, and eventually turned all of the southern-tier EU countries into net importers of labor.

This far-sighted approach to immigration control worked in Europe, and it could work in North America, if we would stop treating unauthorized immigration as a matter of crime and punishment and start looking seriously at measures that would actually decrease the supply of would-be migrants. The developmental approach has gotten short shrift in both Washington and Mexico City, but it is the only approach to immigration control that is likely to reduce illegal migration significantly in the long run. There is virtually complete consensus among academic immigration specialists on this point.

Immigrant contributions to U.S. economic strength and fiscal health

There are numerous potential threats to future U.S. economic strength and fiscal health, but immigration is not one of them. On the contrary, the fact that we are so successful in the global competition for labor is one of our greatest strengths. That competitive edge is perhaps most evident in terms of highly-skilled immigration. In our ability to attract and retain high-skill immigrants, we currently rank fourth in the world, behind Australia, Canada, and Switzerland, but far ahead of Britain, France, Germany, and Japan.

We could be doing better in the global competition for highly skilled immigrants if we did not set an artificially low limit on this kind of immigration. In several recent years, all 65,000 H-1B temporary visas that were made available have been exhausted on the first day of each fiscal year. The Senate’s immigration reform bill would raise the cap on temporary, high-skilled/professional immigration to 115,000, but most experts consider even that number to be inadequate.

We are conspicuously successful in attracting low-skilled immigrants, and it is important to recognize that the influx of these workers is making possible higher rates of growth in numerous labor-intensive industries than would otherwise be possible. Construction, the hospitality industry, and food processing are the most obvious examples.

Most economists believe that large-scale immigration – both low-skilled and high-skilled – is essential to assure robust economic growth, dampen inflationary pressures, and finance intergenerational transfer systems like Social Security and Medicare. Because of low fertility rates, our total labor force growth has already fallen from 5% a year in the 1970s to less than 1% since 1990. And without immigration, our labor force would be shrinking by 3-4% a year.

The contribution of immigration to labor-force growth was most evident during the economic boom of the late 1990s, but even now, with a national unemployment rate of 4.6% — and 3% in Sunbelt cities like San Diego, Las Vegas, and Phoenix – we are below what is conventionally defined as full employment. If immigrants were not entering our labor force in very large numbers, we’d be seriously overheating the economy.

The longer-term implications of immigration for the U.S.’s economic strength and position in the world should not be underestimated. Like all other OECD countries, we have a population-aging problem. We are getting our young, entry-level workers largely from immigration. The contrasting age pyramids for our immigrant and native-born populations tell the story: 35% of our male foreign-born population in 2000 were in prime working age groups, compared with only 24% of the native-born population.

The “dependency ratio” in developed countries in general is set to rise steeply in the next 10 years and beyond. By last year, there were 142 potential labor-force entrants for every 100 potential retirees, but in less than 10 years, there will be only 87 labor-force entrants for every 100 retirement-age people. Europe and Japan have a huge problem, not just because of well-below-replacement-level birth rates but because, for political reasons, they don’t have expansionary immigration policies. There are already very large fiscal imbalances in the health-care and pension systems of these countries. As UC-Berkeley economist David Card recently observed, “They’re going to end up on the back burner of the global economy,” at least in part because their immigration policies are too restrictive.

Immigration at present levels will save the U.S. from labor force decline in the short-to-medium run, but it won’t be enough eventually, because the birth rate among Latino immigrants – our highest-fertility group – is already falling sharply. It’s still well above whites and blacks, but the trend is clearly downward.

In recent years, immigrants have accounted for more than 90% of the labor force growth in some regions of the U.S., like the Mid-West and the Northeast. These regions are experiencing a population implosion because of both low fertility and out-migration by native-born workers. Newly arriving immigrants are heading for these labor-short parts of the country, as well as cities in the Southeast and the Rocky Mountain states that have robust job growth. These “new gateways” for immigration absorbed far more immigrants during the past decade than traditional gateway cities like Chicago and Los Angeles. Migrants from Mexico, in particular, are dispersing themselves geographically to a much greater extent than previous generations of Mexican immigrants — a healthy trend, because it means that they are not piling up in already saturated labor markets where they might depress wages for other workers.

As immigrants have always done, today’s immigrants are filling particular niches in the U.S. economy. In recent years they have accounted for most of the employment growth in occupational categories like cashier, janitor, kitchen workers, landscape maintenance worker, construction worker, and mechanic. The attributes that these jobs have in common are low-skill, low-wage, manual, and often, dirty, repetitive, and dangerous.

In California, immigrants have come to dominate virtually all low-skill job categories, with over 90% of the state’s farm workers, two-thirds of construction workers, and 70% of the cooks in restaurants being foreign-born. At the national level, unauthorized immigrants are heavily concentrated in service occupations, followed by construction and manufacturing. Only 4% of the unauthorized immigrants in the country today are estimated to be working in agriculture. But agricultural work is still the occupation most dominated by unauthorized immigrants. According to recent estimates by the Pew Hispanic Center, about a quarter of all farm workers in the country are illegal immigrants; 17% of all cleaning workers; 14% of all construction workers; and 12% of all food preparation workers.

It is important to recognize that, at this point in time, the U.S. demand for immigrant labor is structural in character. It is deeply embedded in our economy and society. The demand no longer fluctuates with the business cycle. Our research on immigrant-dependent firms in San Diego County since the early 1980s has shown that even during recessions, such employers continue to rely on and hire new foreign-born workers. The job applicant pools of firms that depend heavily on immigrant labor no longer include appreciable numbers of young, native-born workers – and in most cases, natives haven’t been represented for a decade or more. That is partly because there aren’t enough new, native-born entrants to the labor market, but also because of changing attitudes in our society toward manual jobs.

Many immigrant-dependent firms have already tried various alternatives to hiring immigrants but they find no good substitutes. Some businesses may be able to reduce their overall labor requirements through further mechanization, but this option is available mainly to certain types of agricultural employers – not to those in services, retail, and construction.

Are established immigrants and their offspring stuck in the kinds of dead-end, low-wage, manual jobs that are typically held by newly arrived immigrants? Many of first-generation immigrants – particularly Latinos – do have limited occupational mobility. But the data on subsequent generations are much more encouraging: From the first to the second generation, there is considerable movement into white-collar occupations, and out of low-wage service, construction, and agricultural work.

Even within the first generation, there is significant income improvement over time, as immigrants gain new skills, job seniority, and English proficiency. Census data analyzed by the Public Policy Institute of California show that recently arrived immigrants in California have had the steepest decline in poverty since 1993. There is still a large gap between immigrants and natives, but the gap has closed considerably in the last ten years.

The largest gaps in income, education, and occupational status are between Mexico-origin migrants and the native-born population. But even for Mexicans, the big picture is one of progress. There is not much change in occupational status among first-generation Mexican immigrants, but there is a big jump in the second and third generations. In terms of educational attainment, the children of Mexican immigrants are doing conspicuously better than their parents; they have much higher high-school graduation rates. But the high-school drop-out rate is much too high, and college graduate rates are still low.

A major reason why the second and third generations are doing better in terms of occupational and educational mobility is English proficiency. The transition from Spanish to English-dominance usually occurs in just two generations rather than the three generations that it took European-origin immigrants who arrived in the early 20th Century. These 21st Century immigrants don’t need the U.S. Congress to tell them that English is the national language. They universally recognize that English competence is essential to their economic success in the U.S.– and to their children’s success.

Another common misconception is that illegal immigrants are, for the most part, working “off the books” in the underground economy. But all major studies of unauthorized Mexican immigrants completed in the last two decades have found majorities of them working for “mainstream,” formal-sector employers. They get regular paychecks and have state and federal taxes deducted from their earnings.

Among more than 700 Mexican immigrants interviewed by my research team in January-February of this year, after they had returned to their home town in the state of Yucatán, fewer than one-quarter had paid no federal income taxes during their most recent stay in the United States, while 75% had had taxes withheld from their pay, or filed a tax return, or paid taxes both by withholding and tax return. That is clear evidence that these are not “underground” workers contributing nothing to public coffers. While the states and localities that provide services to unauthorized immigrants are disproportionately impacted, this is a revenue-sharing problem that should be addressed through federally financed, immigration impact-assistance programs.

One final point about economic incorporation: Mexicans and other first-generation immigrants tend to have extremely high labor-force participation rates. Illegal immigrants are the most fully employed, with 94% of the men in the work force – significantly higher than native-born Americans. As economist David Card has observed: “These workers may be low-skilled, but they have incredibly high employment rates.” A broad legalization program would increase the U.S.’ rate of return on these immigrant workers by incorporating them more fully and enhancing the human capital that they bring.