Negotiations over a budgetary “grand bargain” failed in 2011 when aspects of the negotiation became public and the two sides grew wary of their supporters finding out what concessions they would be willing to make. Initially, President Barack Obama and House Speaker John Boehner attempted to reach a compromise by negotiating in private but were undermined by leaks about the elements of the potential deal.1Sarah A. Binder and Frances E. Lee, “Making Deals in Congress,” in Political Negotiation: A Handbook, ed. Jane Mansbridge and Cathie Jo Martin (Washington DC: Brookings, 2015), 107. Although both sides were interested in rewriting the tax code, rolling back the cost of entitlements, and cutting the deficit, they didn’t want the public to know exactly which concessions were on the table to accomplish those goals. As noted by one journalist at the time, “Both sides knew that if the most crucial and contested details of their deliberations became public, it would complicate relationships with some of their most important constituencies in Washington—or worse…Obama and Boehner have clung to their separate realities not just because it’s useful to blame each other for the political dysfunction in Washington, but because neither wants to talk about just how far he was willing to go.”

“Politicians do not want to appear as though they are willing to capitulate on issues that these core voters care about.”The gridlock that has overtaken Washington in recent decades means that compromises like the failed “grand bargain” are more critical than ever. Whether it is a compromise between the two parties or within a party, little can be accomplished by a legislature unless individual members agree to compromise and vote in support of proposals that give them part, but not all, of what they want. Yet we have found that nearly a quarter of state legislators vote against such beneficial compromises—even when they move policy toward their own preferred positions. And those who fear voter punishment, especially from primary voters, are more likely to vote against compromises. Politicians do not want to appear as though they are willing to capitulate on issues that these core voters care about.

The “grand bargain” negotiations of 2011 hint at one way to make compromise easier: negotiate in private rather than in public. Privacy is important because it can help limit how much legislators are forced to posture before a critical audience, giving politicians the space they need to solve issues.

The potential benefits of private negotiations

By working in private, politicians can form coalitions on what may otherwise by conflictual issues.2 Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015More Info → Research in social psychology has shown that private negotiations can make individuals more flexible in negotiations by limiting the influence of constituents and audiences and by reducing pressures to save face.3Daniel Druckman, “Determinants of Compromising Behavior in Negotiation: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 38, no. 3 (1994): 507-56. This is, in part, because an important part of reaching a deal is first learning what everyone is willing to give up. If politicians who trust each other can negotiate in private, they can communicate what concessions they are willing to make. Privacy is important in political negotiations—where legislators serve as representatives of their voters and must face those voters in future elections—because politicians do not want their voters to know what they are willing to give up without also showing them what they were able to get in return. If legislators negotiate publicly, by contrast, they are likely to focus on talking points and posturing to their audience rather than putting alternative proposals and compromises on the table. These alternative proposals might put them at risk of being seen as giving in too easily or selling out. As one of the attendees that we surveyed at the 2017 National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) meeting put it: Compromise can be hard when “[legislators] stick to what voters understand (talking points) and not more complicated compromises.”

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015More Info → Research in social psychology has shown that private negotiations can make individuals more flexible in negotiations by limiting the influence of constituents and audiences and by reducing pressures to save face.3Daniel Druckman, “Determinants of Compromising Behavior in Negotiation: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 38, no. 3 (1994): 507-56. This is, in part, because an important part of reaching a deal is first learning what everyone is willing to give up. If politicians who trust each other can negotiate in private, they can communicate what concessions they are willing to make. Privacy is important in political negotiations—where legislators serve as representatives of their voters and must face those voters in future elections—because politicians do not want their voters to know what they are willing to give up without also showing them what they were able to get in return. If legislators negotiate publicly, by contrast, they are likely to focus on talking points and posturing to their audience rather than putting alternative proposals and compromises on the table. These alternative proposals might put them at risk of being seen as giving in too easily or selling out. As one of the attendees that we surveyed at the 2017 National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) meeting put it: Compromise can be hard when “[legislators] stick to what voters understand (talking points) and not more complicated compromises.”

Testing the impact of private negotiations on compromise

We tested the viability of private versus public negotiations at the 2017 NCSL, by renting a booth in the convention center and inviting legislators and staff to take part in a study about negotiations. In total, 208 legislators and 141 staff members took part in the study, standing at tables in the booth and completing a survey experiment on a tablet.

“Each group was told the press has been paying close attention to the issue.”We presented officials who participated in our study with a vignette about negotiation over spending in an area they cared about. In the key part of the vignette they were told that legislators from the opposing party and on the other side of the issue invited the legislator to a discussion in either a closed-door private meeting or a public meeting to work out a compromise. Each group was told the press has been paying close attention to the issue. In the public meeting condition, they were informed that the local paper was expected to attend and report on the meeting, including the back and forth of proposals and counterproposals. This highlighted that alternatives the legislator proposed or considered would be visible to constituents. By contrast, participants in the private negotiation were informed that no press would be allowed at the meeting. Instead they were told that the local paper was interested in reporting on the final outcome of the negotiation. This kept the issue salient, but implied that the back and forth of any negotiation would be kept private.

Participants in both the public and private negotiations were then asked how likely they would be to meet to discuss this issue in the (public or private) meeting, and, if they did meet, how likely they would be to reach a compromise that both sides would support.

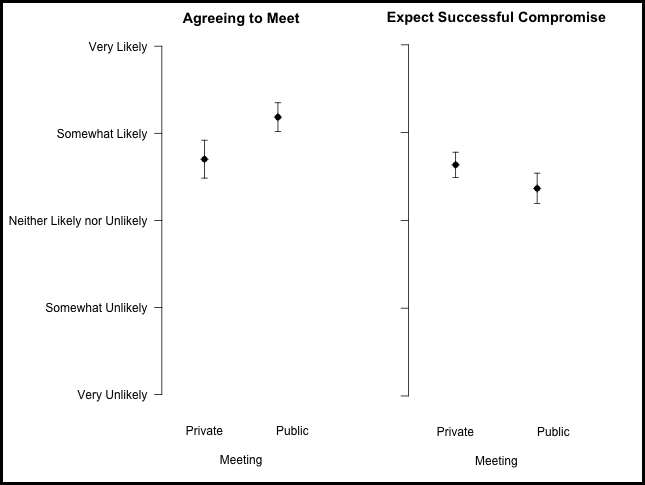

Figure 1: Meeting types vs. legislators’ agreement to meet and compromise

Figure 1 shows that legislators think politicians will be more likely to meet when they are invited to bargain in a public meeting, but they are also less likely to think that they will reach a compromise agreement. Legislators appear to recognize the dilemma they face when trying both to find a compromise, and to remain in good standing among their constituents.

These results are consistent with electoral incentives shaping politicians’ expectations about bargaining. On the one hand, private meetings can insulate politicians from the very voters who would punish them for compromising. Private meetings can allow politicians to negotiate without fear that primary voters—the constituents most likely to demand that they not compromise—will learn of concessions they are willing to make before learning about policy victories. If a deal is reached, then politicians can risk revealing the concessions they made and try to assuage voter anger by also revealing the compromise solution and what that offers in terms of benefits as well. On the other hand, private meetings may be less attractive because legislators do not want to alienate voters by appearing to be secretive.4Mark E. Warren, Jane Mansbridge, and Max A. Cameron with André Bächtiger, Simone Chambers, John Ferejohn, Alan Jacobs, Jack Knight, Daniel Naurin, Melissa Schwartzberg, Yael Tamir, Dennis Thompson, and Melissa Williams, “Deliberative Negotiation,” in Political Negotiation: A Handbook, ed. Jane Mansbridge and Cathie Jo Martin (Washington DC: Brookings, 2016), 178. Legislators work hard to gain voters’ trust and may worry that private negotiations will jeopardize that trust.

Private negotiation in practice

“This does not mean that governing should be done entirely in private; such a remedy would be worse than the problem of gridlock.”These results demonstrate that individuals and groups interested in increasing the likelihood that politicians identify and pass compromise deals need to find a way to insulate the elected officials during the negotiation phase. Of course, this does not mean that governing should be done entirely in private; such a remedy would be worse than the problem of gridlock. Voters should learn about the policies that governments pass and they should hold politicians accountable when they do not like the policies that are passed. In the face of rejection of compromise that may prevent the passage of legislation that improves on current policy, however, this evidence indicates that politicians can and should be given some privacy during the negotiation process so they can consider effective compromise solutions.