With the growth of ideological and partisan polarization, the two parties in Congress are in seemingly constant disagreement over the major issues that face the country. A cause and consequence of this increasing polarization is the decline of moderate legislators who, based on their voting records, occupy an ideological middle ground between the two parties.1See Richard Fleisher and John R. Bond, “The Shrinking Middle in the US Congress,” British Journal of Political Science 34, no. 3 (2004): 429–451; Danielle M. Thomsen, Opting Out of Congress: Partisan Polarization and the Decline of Moderate Candidates (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018). Although the ranks of moderate legislators has dropped off in recent decades, these members can still play a pivotal role, especially in the Senate, in deciding whether a bill passes or fails or a nominee is confirmed or not. As a result, moderates may be in a unique position to garner interest from the media and potentially shape public opinion on an issue. My research suggests moderates have the ability to cultivate national reputations that differ from more traditionally liberal or conservative legislators, although this reputation does not appear to translate into a unique ability to affect public opinion toward legislation.

Media and public attention to Senate moderates

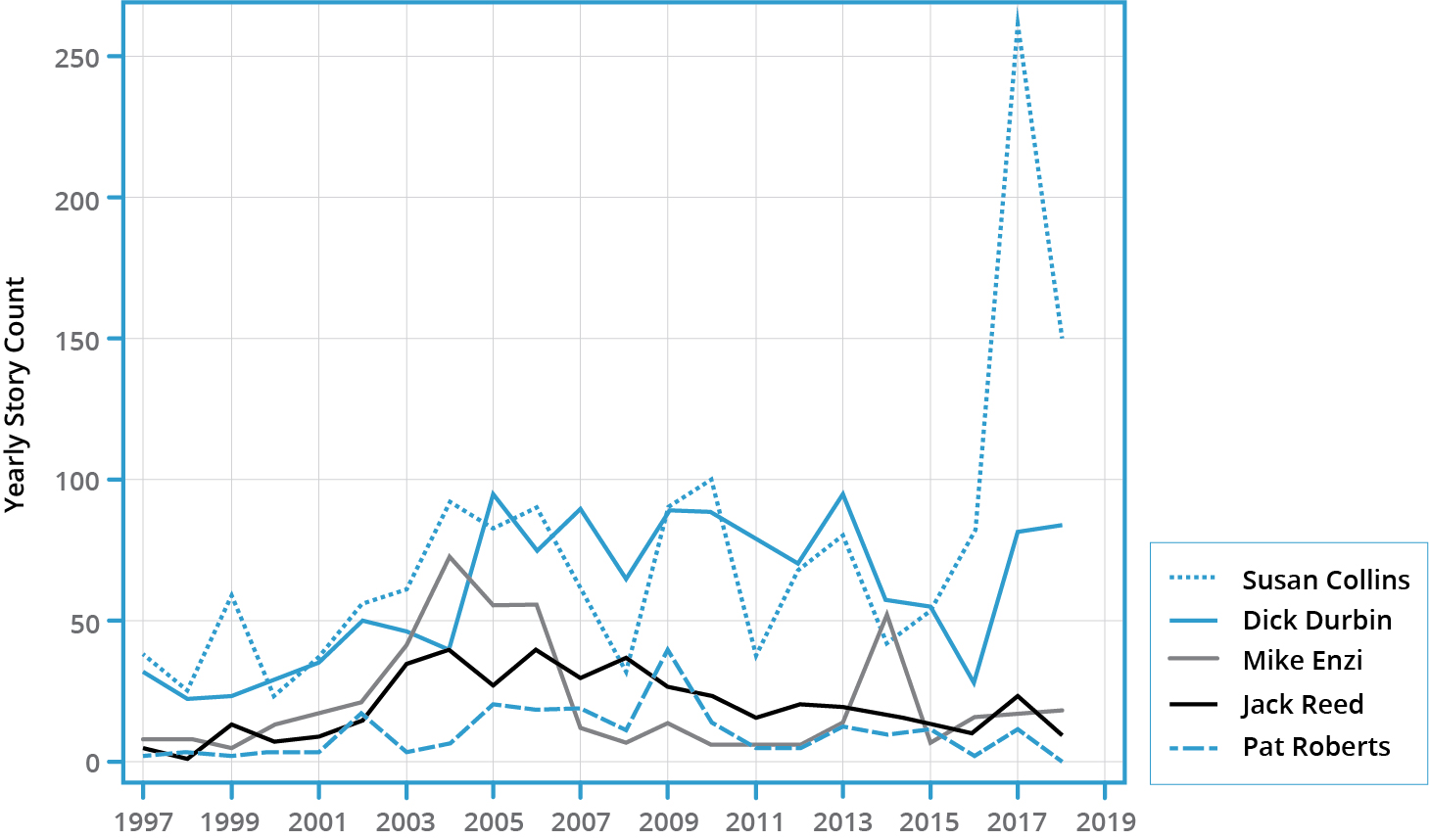

The potential for moderates to exert influence in the contemporary Congress is highlighted by the considerable media attention devoted to Senator Susan Collins (R-ME), the chamber’s most liberal Republican. Figure 1 shows the yearly New York Times mentions of the five current senators who were first elected to Congress in 1996. Of the five, Collins has the highest average number of stories per year, with 73.9. Coverage of Collins actually outpaces Dick Durbin (D-IL) during this time period, despite Durbin’s position in the Democratic leadership in the Senate. In fact, out of 53 senators first elected in the 1990s, Collins averaged more New York Times stories per year than all but five senators.2The five senators elected in the 1990s who averaged more stories are Chuck Schumer (D-NY), John Edwards (D-NC), Robert Torricelli (D-NJ), Bill Frist (R-TN), and Dianne Feinstein (D-CA). These numbers are based on a search of the ProQuest New York Times database for variations of the senators’ name. I thank Ben Sullivan for his research assistance. Although research suggests Senate moderates may try to shy away from the spotlight,3Neilan S. Chaturvedi, “Kings of the Hill? An Examination of Centrist Behavior in the US Senate,” Social Science Quarterly 98, no. 5 (2017): 1250–63. the media coverage data indicates that may not always be feasible.

Figure 1. New York Times coverage of senators first elected in 1996

The media’s interest in ideologically atypical senators like Collins could be a result of novelty of these legislators in a more polarized chamber4 Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2017More Info → or the fact that their votes may be seen as particularly pivotal.5Brian J. Fogarty, “National News Attention to the 106th Senate,” Politics 33, no. 1 (2013): 19–27. As a result of this media attention, moderates may have a greater ability to develop a national reputation than their typical copartisans in Congress.

Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2017More Info → or the fact that their votes may be seen as particularly pivotal.5Brian J. Fogarty, “National News Attention to the 106th Senate,” Politics 33, no. 1 (2013): 19–27. As a result of this media attention, moderates may have a greater ability to develop a national reputation than their typical copartisans in Congress.

To assess whether this is the case, and what this might mean for such senators’ influence on public opinion, I fielded a survey in the summer of 2019. Respondents were recruited for the survey by Qualtrics, and were matched to the US population on the dimensions of age, gender, race, and region.6A quota was also used to obtain a relatively even balance of Republicans and Democrats. Although this is a diverse, national sample, it is important to note here that it is not a nationally representative one. The survey asked respondents whether they had a favorable or unfavorable impression of eight senators—four Democrats and four Republicans—randomly selected from a list of 20 senators. Respondents were also given an option to select “never heard of this person.” The 20 senators asked about included Susan Collins (R-ME) and Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), who are the two most moderate Republican senators based on roll call vote measures,7Jeffrey B. Lewis, Keith Poole, Howard Rosenthal, Adam Boche, Aaron Rudkin, and Luke Sonnet, Voteview: Congressional Roll-Call Votes Database, 2019, https://voteview.com/. and Joe Manchin (D-WV) and Doug Jones (D-AL), who are the two most moderate Democrats.8For purposes of comparability, the other senators asked about were mostly those who began serving in Congress at the same time as Collins, Murkowski, Manchin, and Jones, as well as senators from the more liberal wing of the Democratic Party and more conservative wing of the Republican Party.

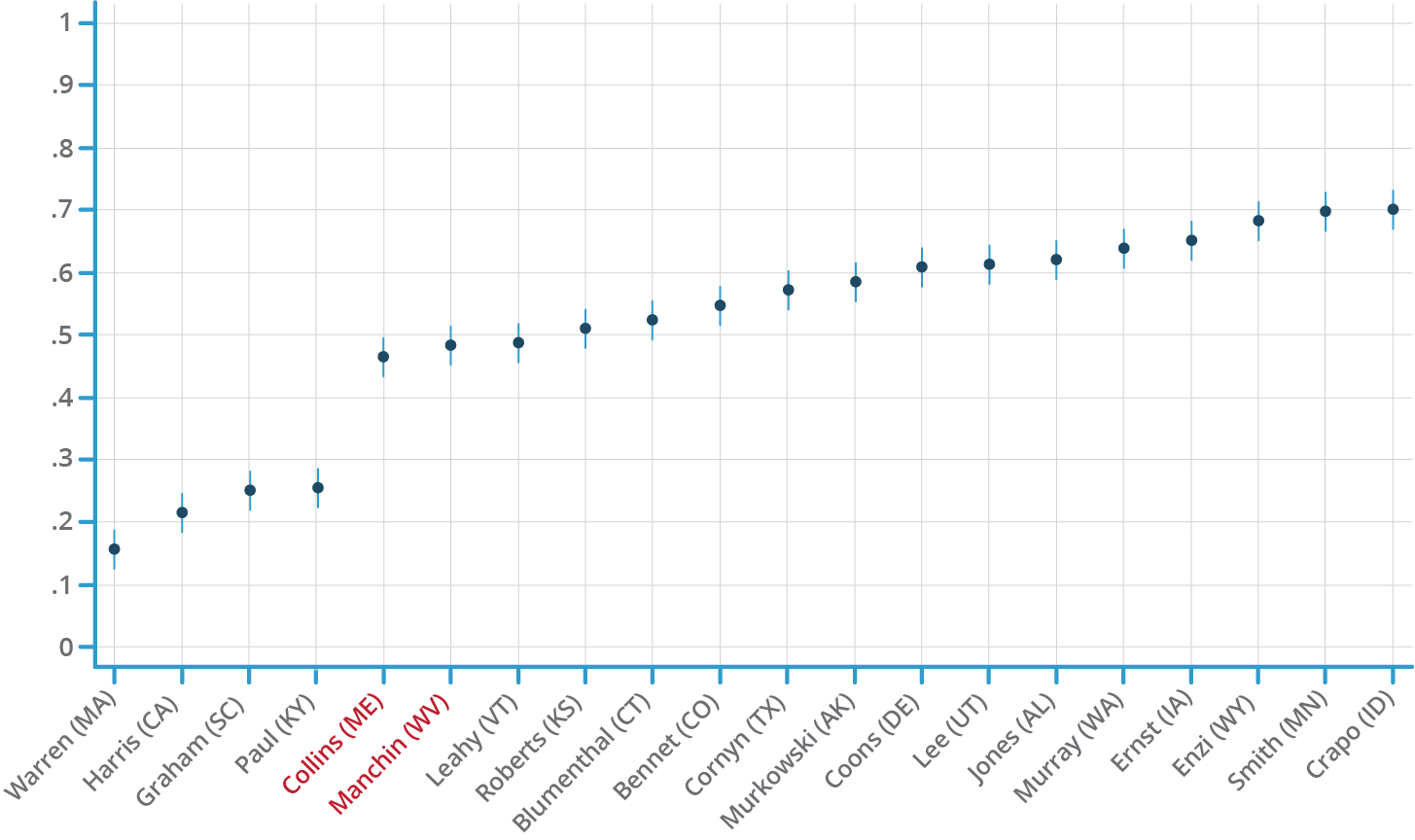

I asked each survey respondent to rate only eight out of the 20 senators to not overburden them. The result is that not all respondents rated all senators, but each senator was rated by about 40 percent of respondents, or roughtly 550 people. To measure name recognition, I looked at the proportion of respondents who selected “never heard of this person,” shown in Figure 2, along with 95 percent confidence intervals. Senators on the left hand side of the figure are better known than senators on the right hand side of the figure.9As noted above, this is not a nationally representative sample, so these numbers should not be viewed as representative of senators’ name recognition in the public at large. The primary purpose of this section is to compare the relative levels of name recognition of these senators.

Figure 2. Proportion of respondents who say they have not heard of a senator

The results indicate that the two most moderate members of their party—Collins and Manchin—have relatively high levels of name recognition. Collins and Manchin (highlighted in red in Figure 2) had the fifth and sixth highest name recognition of the 20 senators asked about. The four senators with higher name recognition than Collins (Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, Rand Paul, and Lindsey Graham) all ran for their party’s presidential nomination in 2016 or 2020.10Collins had a higher name recognition than 15 senators, with 12 of the 15 differences being statistically significant at p < 0.05. Manchin had higher name recognition than 14 senators, with 11 of the differences being statistically significant at p < 0.05. It is important not to overstate how well-known Collins and Manchin are, with over 40 percent of respondents saying they had never heard of the senators. The survey does suggest, however, that these more ideologically atypical senators find their way into the public discourse more than many of their typical partisan counterparts.

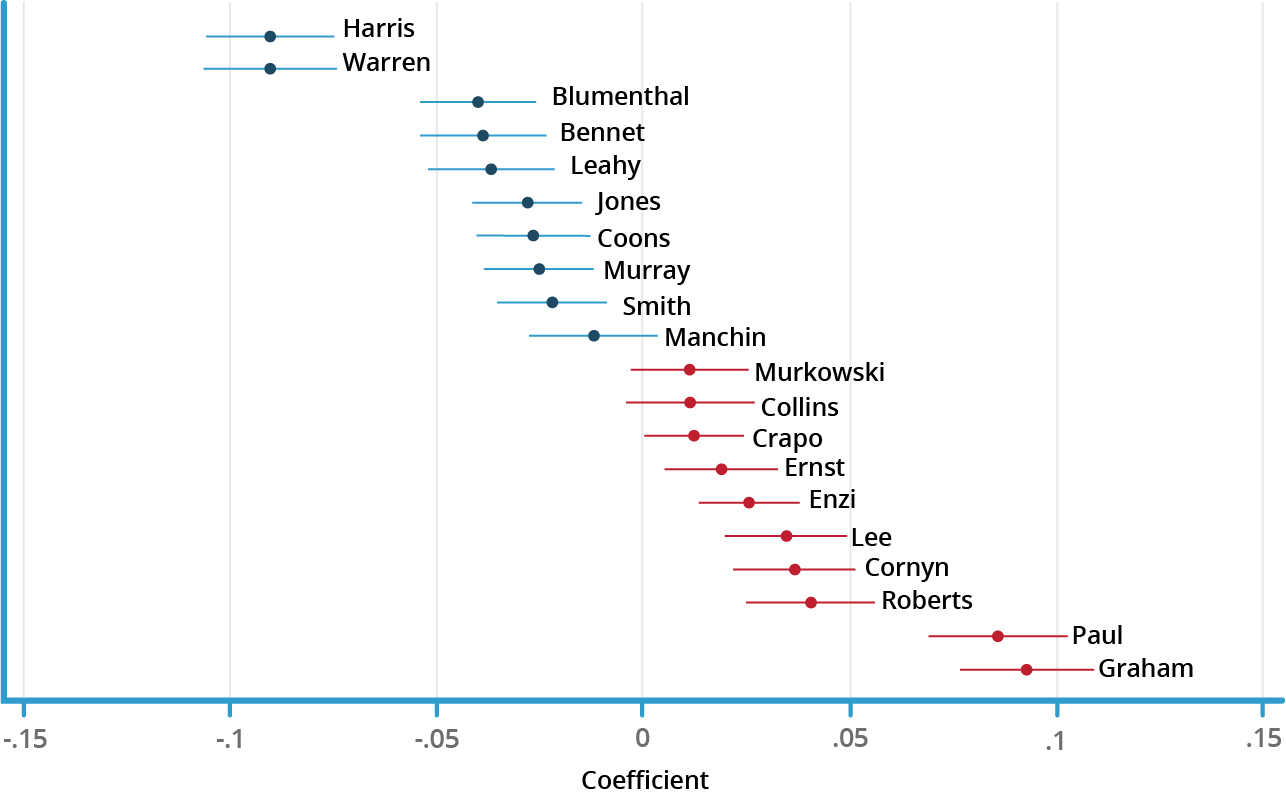

The survey results also indicate that Collins and Manchin are evaluated differently than their copartisans in the Senate, at least at the national level. Figure 3 shows the coefficients and 95 percent confidence intervals from OLS regression models where the dependent variable is coded “1” if the respondent gave the senator a rating of “favorable” and “0” otherwise.11Although the dependent variable is dichotomous, I use OLS regression for ease of interpretation. The coefficients represent the change in the probability of approval for a one-unit change in the seven-point party ID scale, where higher responses are more pro-Republican. The results are substantively similar if a logistic regression model is used instead of OLS. The only independent variable in the models is a standard seven-point party identification variable (ranging from strong Democrat to strong Republican). For Democratic senators, we would expect the coefficient for each senator to be negative and statistically significant, indicating that as a respondent moves in the pro-Republican direction on the party ID scale they are less likely to have a favorable opinion of the senator. The coefficient for Republicans should be positive and statistically significant. The farther the coefficient is from the 0 line, in either direction, the stronger the relationship between party ID and senator favorability. The figure shows that for 17 out of 20 senators, the coefficient is statistically significant and in the expected direction. For three senators—Collins, Manchin, and Murkowski—the coefficient is close to zero and does not reach conventional levels of statistical significance. In other words, evaluations of these senators are not as well-explained by party as they are for other senators, which is what we would expect if their moderate reputation has filtered down to the public.12These models do not include controls, and are used simply to illustrate the bivariate relationship between party ID and approval of each senator.

Figure 3. Relationship between party ID and favorability of senators13Democrats are in blue and Republicans in red; lines are 95 percent confidence intervals.

Do moderates have unique effects on public support for legislation?

The survey also included an experiment designed to test whether moderates’ positions have a causal effect on public support for legislation distinct from more traditional liberal or conservative legislators. Respondents read about two pieces of legislation introduced in the Senate. The first bill, sponsored by Mike Crapo (R-ID), would permanently extend a railroad tax credit for the repair and upgrade of certain railroad lines. The second bill, introduced by Patrick Leahy (D-VT), would make it easier for generic drug makers to sue brand-name pharmaceutical companies to obtain materials needed to make generic drugs. Both bills were cosponsored by Susan Collins and Rand Paul. According to my survey, Paul is both relatively well known and evaluations of him are considerably more partisan than evaluations of Collins. Paul therefore makes for a good test case for whether voters respond differently when legislation is supported by a more moderate senator like Collins compared to a more conservative senator like Paul.

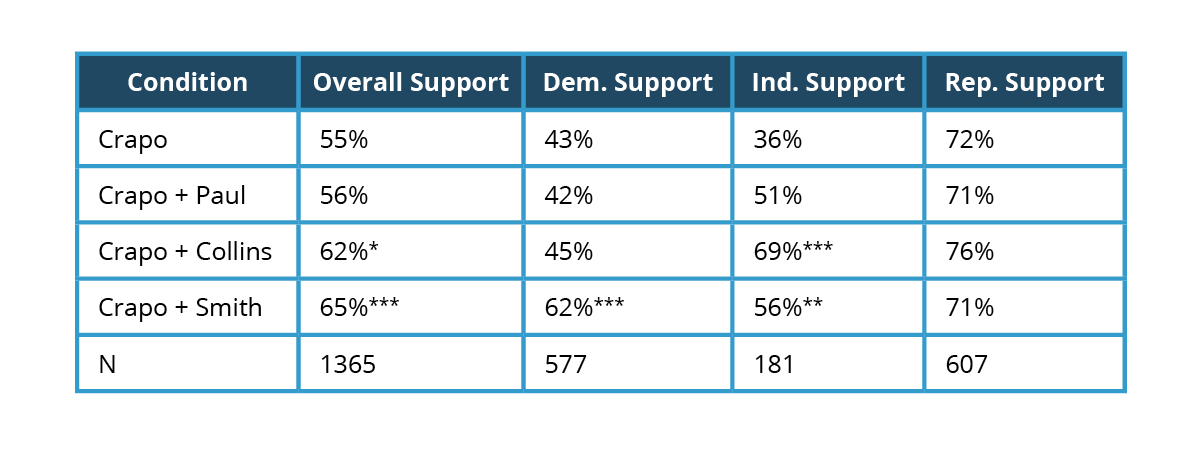

For the railroad tax bill, all respondents read a short description of the bill, including opinions of supporters and opponents. Respondents were then randomly assigned into one of four conditions. The first condition told respondents the bill was sponsored by Republican Mike Crapo of Idaho. The second condition told respondents the bill was sponsored by Crapo and cosponsored by Republican Rand Paul of Kentucky. The third condition told respondents the bill was sponsored by Crapo and cosponsored by Republican Susan Collins of Maine. Finally, the fourth condition told respondents the bill was sponsored by Crapo and cosponsored by Democrat Tina Smith of Minnesota. Table 1 shows the percentage of respondents who support the bill across the four conditions. The first column shows overall support across all respondents while the next three columns show support among partisan subgroups.

Table 1. Percentage of respondents supporting the railroad bill by party affiliation and condition14*p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01; indicates whether condition differs from Crapo-only condition.

Table 1 provides suggestive evidence that respondents evaluated the bill differently when Collins is listed as a cosponsor compared to Paul. With Paul as cosponsor, overall support for the bill is essentially unchanged from the condition that simply lists Crapo (56 percent support compared to 55 percent support). Support for the bill increases to 62 percent when Collins’ name is attached, and the mean level of support in this condition is statistically different from the control condition at p < 0.10. The difference between the Crapo + Paul and Crapo + Collins conditions, however, is not statistically significant at conventional levels (p = 0.16). When broken down by party identification, the results suggest that most of the increased support is driven by independents, who approve of the bill at substantially higher levels when Collins is listed as a cosponsor (a 33-percentage-point increase relative to the control condition).15A pairwise comparison indicates no statistically significant differences in support for the bill among independents when Collins is the cosponsor or when Smith is the cosponsor (p-value = 0.17). This finding makes sense if Collins’ moderate reputation endears her to independents in particular. That said, the number of independents is relatively small (N = 181), and among Democrats, a larger group who should like Collins more than Paul, we see little evidence of increased support when Collins’ name is attached to the bill. By way of comparison, when Democrats read that Tina Smith (D-MN) cosponsored the bill, their support for the bill increases by nearly 20 percentage points, while it only increases by two percentage points when Collins’ name is attached relative to the control.

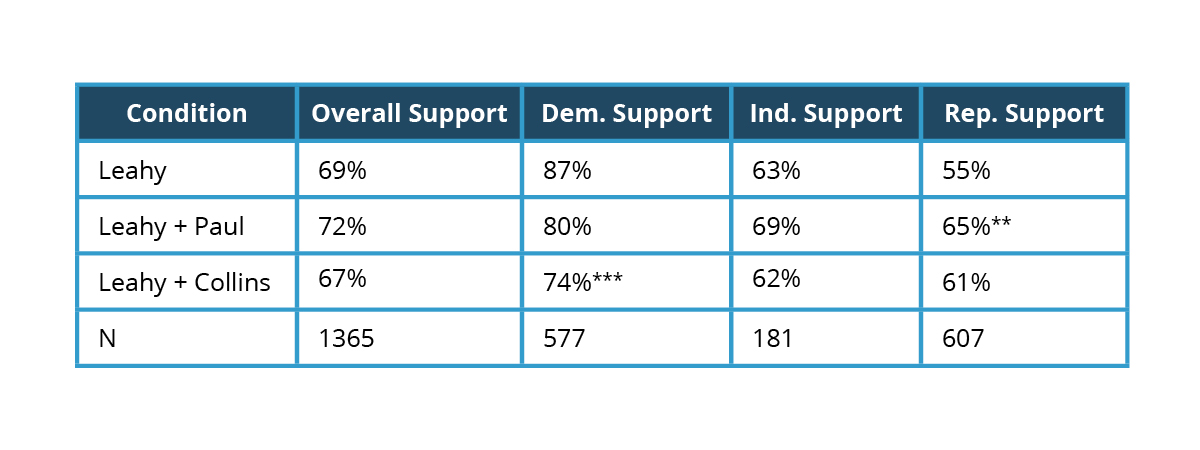

For the experiment with the prescription drug bill, respondents were assigned to one of three conditions. Respondents in the first condition read that the bill was sponsored by Democrat Patrick Leahy of Vermont. Respondents in the second condition read that the bill was sponsored by Leahy and cosponsored by Paul, while respondents in the third condition read that the bill was sponsored by Leahy and cosponsored by Collins. Since this bill was originally sponsored by a Democrat, I did not include a fourth condition that introduced another Democratic cosponsor. Table 2 shows support for the drug bill across the different conditions. Similar to Table 1, overall support is listed in the first column with the next three columns showing support across different partisan subgroups.

Table 2. Percentage of respondents supporting the drug bill by party affiliation and condition16*p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01; indicates whether condition differs from Leahy-only condition.

As expected, support for the bill increases among Republicans when Rand Paul is listed as a cosponsor while support among Democrats declines, although the seven-percentage-point decline among Democrats is not statistically significant (p = 0.13). In an unexpected result, however, Democratic support for the bill is lowest when Collins is listed as cosponsor. In the Leahy-only condition, 87 percent of Democrats support the bill, compared to 74 percent in the Leahy + Collins condition (the difference between conditions is statistically significant at p < 0.01). Perhaps even more surprising, support for the bill is actually higher among Democrats in the Leahy + Paul condition (80 percent) than the Leahy + Collins condition (74 percent), although the difference between these two conditions is not statistically significant at conventional levels (p = 0.102). In addition, independents do not support the drug bill at higher rates in the Collins condition, which runs counter to the results in the first experiment. In sum, across the two experiments, there is a lack of consistent evidence that the endorsement of Susan Collins and Rand Paul have markedly different effects on levels of support for legislation across partisans.

Although the findings are not always consistent across the two bills, one consistent finding is that attaching Collins’ name to legislation does not improve Democrats’ evaluations of the bill relative to Paul. There are several possible explanations for this null finding. For one, the survey was conducted less than a year after Collins’ vote to confirm Brett Kavaugh to the US Supreme Court. Polling suggests this high-profile vote may have polarized support for Collins along party lines, at least in Maine. It is also possible that voters are largely unaware of the ideological positions of Collins and Paul. As noted above, however, at least among respondents in this survey, evaluations of Collins were less partisan than evaluations of Paul. This fact would suggest voters do not see Collins and Paul as simply interchangeable Republican senators. Instead, the experimental results suggest Democrats are not more inclined to take positive cues about a piece of legislation when it is supported by a moderate Republican compared to a conservative Republican.

Conclusion

The results from the survey suggest the most moderate senators from each party have relatively high levels of name recognition nationally and are evaluated differently than many of their more traditional copartisan legislators. The experimental results, however, suggest that when moderates attach their name to legislation it does not necessarily have unique effects on public support or opposition to that legislation. Of course, this is only one potential way in which moderates could be influential players in the contemporary Congress. The larger project examines not just whether moderates can influence public opinion, but also how they seek to assert influence inside the institution and position themselves to survive electoral challenges in a more polarized political climate.