The sharp rise in partisan polarization in Congress has been one of the most prominent topics of academic debate for the past decade. One of the most commonly cited explanations for polarization is the primary election system. The conventional wisdom is that primary voters pull candidates away from the center and toward the ideological extremes. Despite the logical appeal of this argument, scholars have been more skeptical of the linkages between primaries and polarization. First, the evidence that ideologues fare better in primaries is mixed,1→David W. Brady, Hahrie Han, and Jeremy C. Pope, “Primary Elections and Candidate Ideology: Out of Step with the Primary Electorate?,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 32, no. 1 (2007): 79–105.

→Andrew B. Hall and James Snyder, “Candidate Ideology and Electoral Success” (working paper, Harvard University, 2015).

→Shigeo Hirano et al., “Primary Elections and Partisan Polarization in the US Congress,” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 5, no. 2 (2010): 169–191. and across studies, the magnitude of the effect of candidate ideology on primary outcomes is small.2Hall and Snyder, “Candidate Ideology and Electoral Success.” Differences in primary rules also seem to matter little for polarization. Closed primaries, or those in which only party members can vote, do not produce more extreme candidates than open primaries.3→Eric McGhee et al., “A Primary Cause of Partisanship? Nomination Systems and Legislator Ideology,” American Journal of Political Science 58, no. 2 (2013): 337–51.

→Jon C. Rogowski and Stephanie Langella, “Primary Systems and Candidate Ideology: Evidence from Federal and State Legislative Elections,” American Politics Research 43, no. 5 (2015): 846–871.

But also see Elisabeth R. Gerber and Rebecca B. Morton, “Primary Election Systems and Representation,” Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 14, no. 2 (1998): 304–324.

Additional evidence on the limited effect of partisan primaries on polarization comes from recent reforms. Most notably, the implementation of the top-two primary in 2012 in California was predicted to increase turnout, diminish the effect of extreme voters, and ultimately help moderate candidates. However, moderates have fared no better under the top-two primary than in closed primaries,4Douglas J. Ahler, Jack Citrin, and Gabriel S. Lenz, “Do Open Primaries Improve Representation? An Experimental Test of California’s 2012 Top-Two Primary,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 41, no. 2 (2016): 237–68. and if anything, California lawmakers took more extreme positions after the adoption of the top-two primary.5Thad Kousser, Justin Phillips, and Boris Shor, “Reform and Representation: A New Method Applied to Recent Electoral Changes,” Political Science Research and Methods 6, no. 4 (2017): 809–827. Ahler, Citrin, and Lenz attribute the failure of the reform to the fact that voters are largely unaware of the ideological orientation of candidates.6Ahler, Citrin, and Lenz, “Do Open Primaries Improve Representation?”

The aim of this project is to examine the degree to which primary voters prefer ideologues to moderates and to better understand how malleable their preferences are. Do primary voters want liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans? And, how might they be persuaded to support candidates in the political center? The answers to these questions would be valuable information for practitioners and elected officials alike who bemoan the rise of polarization and want to diminish the gulf between the parties. Many groups, both within and outside of Congress, are devoting resources to ideologically centrist and pragmatic politicians. For example, the Blue Dog Coalition and the New Democrat Coalition on the Democratic side endorse and support moderate candidates, and the Republican Main Street Partnership raises money to protect moderate incumbents. These organizations, among others, often make appeals to elect more ideologically centrist and pragmatic politicians, but it is unclear whether these appeals can compel voters, especially primary voters, to support moderate candidates.

Research methodology

It is difficult to examine levels of support for ideological moderates with electoral data because they are much less likely to run for Congress than those at the extremes.7→Andrew B. Hall, Who Wants to Run? How the Devaluing of Political Office Drives Polarization (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019).

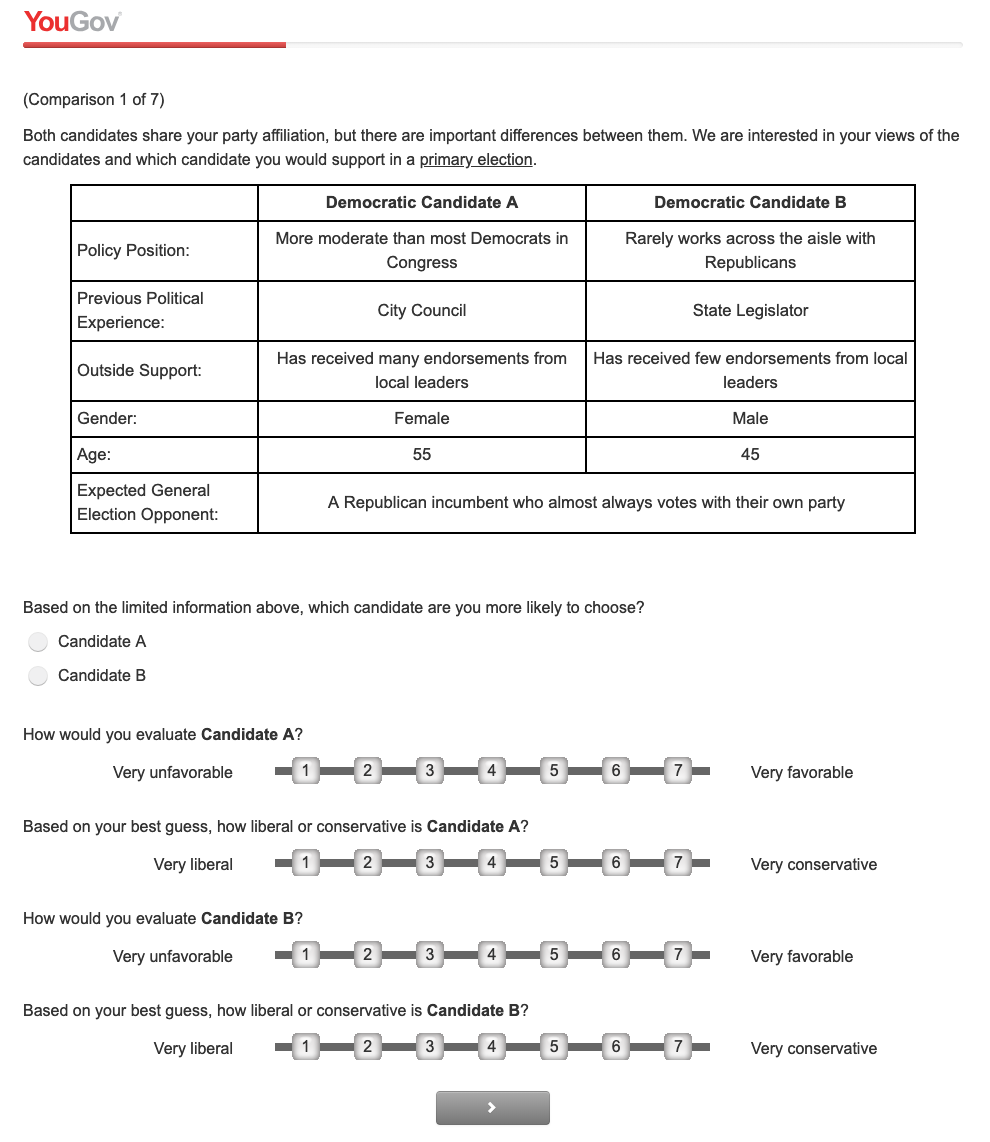

→Danielle M. Thomsen, Opting Out of Congress: Partisan Polarization and the Decline of Moderate Candidates (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018). To gauge whether primary voters would support a moderate candidate, I conducted a survey of 1,000 primary voters from both parties to examine their preferences of hypothetical candidates. The sample of validated primary voters (rather than general election voters) is an important feature of this project that distinguishes it from other research on the topic. I conducted a conjoint experiment, which allowed me to manipulate multiple candidate attributes (ideology, experience, viability, gender, age, and incumbent bipartisanship) and assess the relative impact of each for voter preferences. The main attribute of interest is candidate ideology, particularly whether he or she is ideologically moderate or extreme.

Figure 1. Screenshot of the survey

Candidate ideology is conveyed in two ways in the survey: first, whether the candidate is more moderate or more extreme than members of their party, and second, whether the candidate does or does not work across the aisle with the other party.8For Democratic (Republican) primary voters, candidates were described in one of the following four ways: (1) more moderate than most Democrats (Republicans) in Congress, (2) more liberal (conservative) than most Democrats (Republicans) in Congress, (3) rarely works across the aisle with Republicans (Democrats), or (4) often works across the aisle with Republicans (Democrats). We can think about these as ideological and partisan dimensions, respectively, and I included both dimensions in my survey to examine whether they operated similarly among primary voters. Furthermore, we often hear real-world candidates describe themselves in both ideological and partisan terms, and I wanted to examine how primary voters viewed candidates with these different labels.

Preferences of primary voters

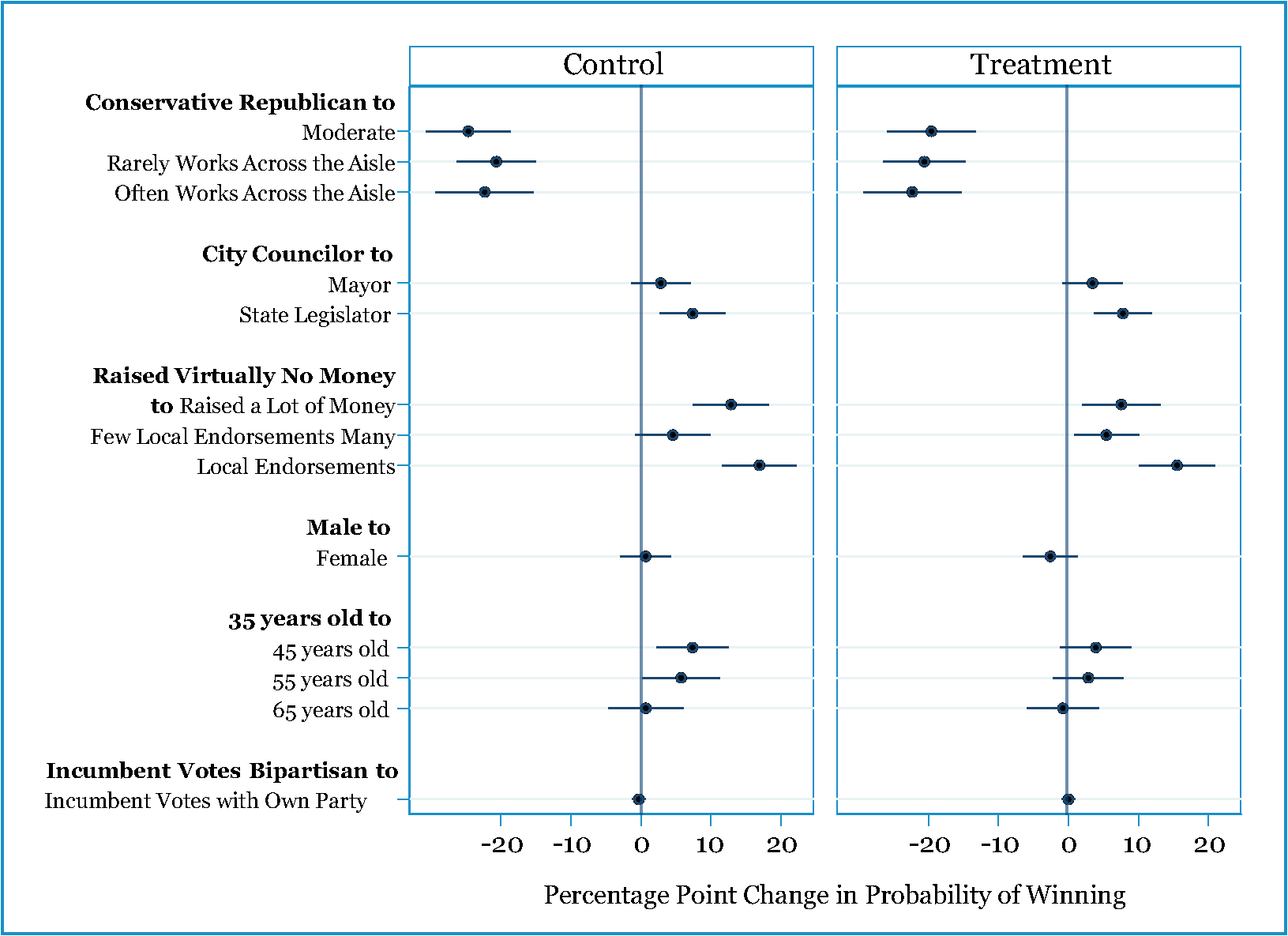

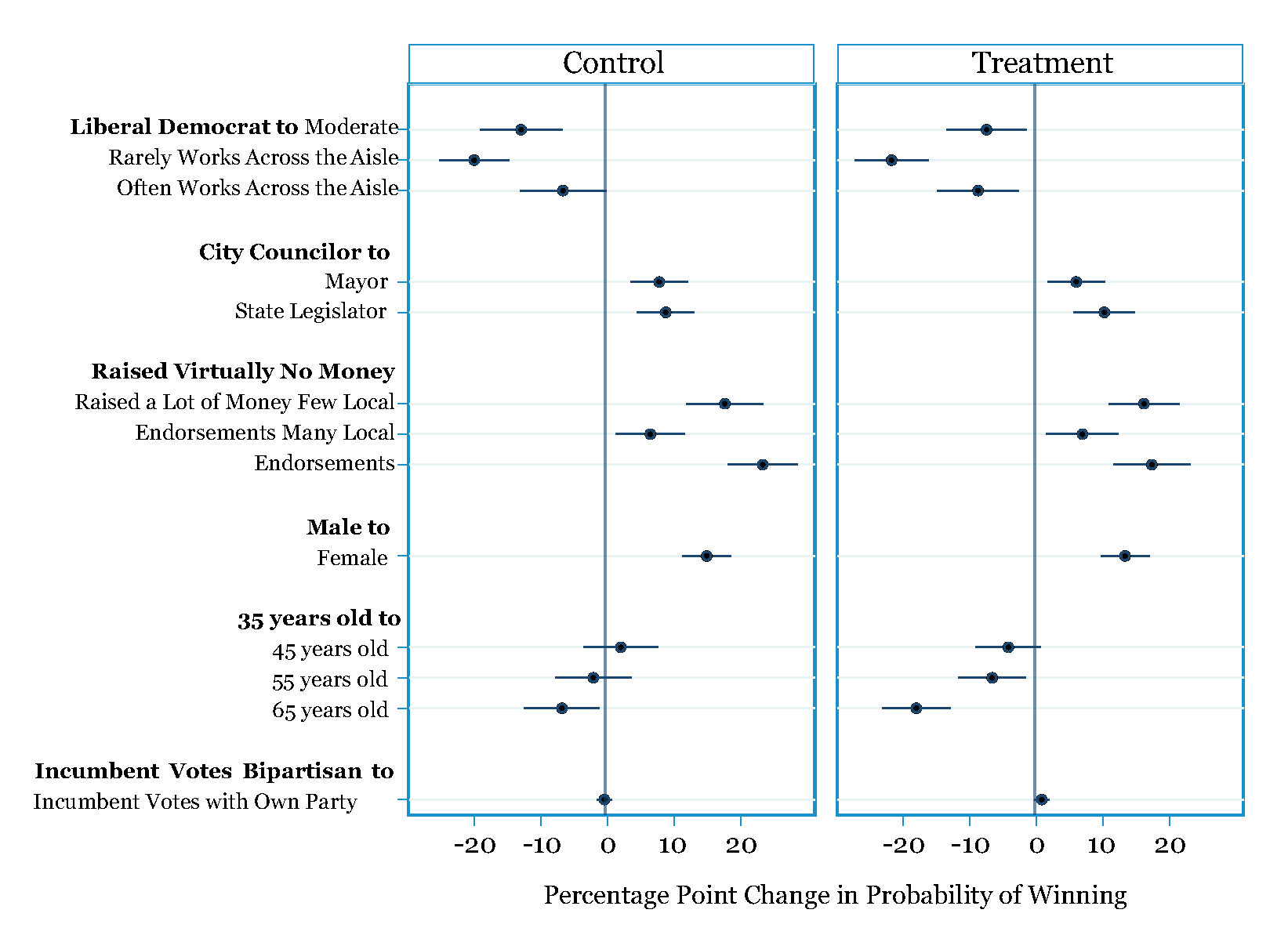

To assess the level of support for moderates versus ideologues, respondents were asked to evaluate each candidate and to state which candidate they would vote for across seven pairs of same-party candidates. Figure 2 shows how the probability of winning changes when Democratic or Republican candidates are described as more liberal or conservative than their party, respectively, to (1) more moderate than their party, (2) rarely works across the aisle with the other party, and (3) often works across the aisle (see the top three rows). We can see, first, that Democratic primary voters prefer liberal Democratic candidates and Republican primary voters prefer conservative Republican candidates over all other types. The probability of winning decreases for moderates, those who rarely work across the aisle, and those who often work across the aisle. However, the moderate and bipartisan penalty is smaller for Democrats than it is for Republicans.

An unexpected result to emerge is that candidates who are described as “rarely work across the aisle” are viewed differently by primary voters than those who are described as liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans. Across the four types, Democratic primary voters are the least likely to vote for these candidates. Republican primary voters are much less likely to vote for these candidates than they are for conservative Republicans, but as likely to vote for these candidates as they are for moderates and those who often work across the aisle.

Figure 2. Probability of winning primary between those described as liberal and conservative

Does priming partisan conflict change voter preferences?

The second goal of the project was to see how support for moderates changed when voters were presented with information about partisan conflict in Congress. It is quite clear that most Americans are frustrated with the hyperpartisanship in Washington, and party gridlock and bickering is consistently named among the top reasons for voter disapproval of Congress. The main expectation was that primary voters would be more likely to support moderates or candidates who worked across the aisle if they received the information below:

“We are interested in the preferences of American voters in an era of extreme partisan polarization.

As you may know, partisan conflict in Congress is now at an all-time high. A lot of Americans are concerned about partisan bickering in Washington because Congress is not getting things done and not solving national problems. The recent shutdown of the government was the longest one in history.

Some have argued that partisan fights harm our national interests and that the dysfunction in Washington is bad for American citizens. The future of bipartisanship in Congress ultimately depends on the candidates that voters choose on Election Day.”

However, I found little support for this expectation. The graphs below, which are broken down by Republican (Figure 3) and Democratic (Figure 4) primary voters, show the change in support for moderate and bipartisan candidates if primary voters did and did not receive the additional text that mentioned contemporary polarization in Congress (“treatment” and “control” panels, respectively). The patterns look similar across treatment and control groups and similar to those highlighted above.

Figure 3. Republican Party primary voter preference

Figure 4. Democratic Party primary voter preference

As discussed above, this project sought to learn more about electoral support for moderate candidates and to better understand whether moderates can leverage the current state of partisan politics in Congress to gain votes from those who are believed to be hostile to their candidacies.

The findings here have important implications for our understanding of how malleable the preferences of primary voters are and how effective partisan conflict appeals may be. On the one hand, primary voters prefer liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans over moderate and bipartisan candidates. Yet, primary voters do not give similar levels of support to candidates who rarely work with the other party. Particularly among Democrats, there is some electoral value to working across the aisle over not working across the aisle. There may also be important differences across strong and weak partisans that were beyond the focus here, but in general, it appears that primary voters operate within an ideological framework for candidate selection. It is not clear they are always aware of these differences across candidates in real-world elections, but when that information is available, they will likely favor liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans. Groups in the political middle would be wise to learn more about how to craft appeals to increase support for moderates. That may be one way to bring the parties closer together and counteract recent polarizing trends.

References:

→Andrew B. Hall and James Snyder, “Candidate Ideology and Electoral Success” (working paper, Harvard University, 2015).

→Shigeo Hirano et al., “Primary Elections and Partisan Polarization in the US Congress,” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 5, no. 2 (2010): 169–191.

→Jon C. Rogowski and Stephanie Langella, “Primary Systems and Candidate Ideology: Evidence from Federal and State Legislative Elections,” American Politics Research 43, no. 5 (2015): 846–871.

But also see Elisabeth R. Gerber and Rebecca B. Morton, “Primary Election Systems and Representation,” Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 14, no. 2 (1998): 304–324.

→Danielle M. Thomsen, Opting Out of Congress: Partisan Polarization and the Decline of Moderate Candidates (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018).