During the 107th Congress, President George W. Bush faced little pushback from the Republican Congress in enacting tax cuts that involved sending “rebate checks” to many Americans. After all, the Republican Party had long embraced reducing marginal tax rates as a signature policy issue that continuously appeared as a campaign pledge. Six years later, a Democratic-controlled 111th Congress encountered intransigent party members when they enacted the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Strongly advocated for by President Barack Obama and a long-term policy goal of many Democrats, the legislation proved difficult to pass. Leaders in both chambers were forced to make numerous concessions in order to garner the requisite votes for passage while they also maximized the procedural tools in order to overcome Republican obstruction. The bill was a major policy win for liberal Democrats, but electorally, it was painful: House Democrats lost 61 seats as well as their majority in the 2010 election. One estimate of the electoral impact of the vote for the ACA attributes the loss of 25 of these seats to this one policy.1Brendan Nyhan et al., “One Vote Out of Step: The Effects of Salient Roll Call Votes in the 2010 Election,” American Politics Research 40, no. 5 (2012): 844–879.“Leaders in both chambers were forced to make numerous concessions in order to garner the requisite votes for passage while they also maximized the procedural tools in order to overcome Republican obstruction.”

Though both houses of Congress were under the control of one party, the process for passing each policy differed greatly. Members of Congress typically arrive in Washington, DC, with a set of policy-related goals, whether they be new policy initiatives or changes to existing policies, and they often look for opportunities to “claim credit” for government programs that benefit their constituencies.2See David Mayhew, Congress: The Electoral Connection (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1974). They also face an election calendar that forces them to constantly raise campaign funds and make other preparations for the next election cycle. These aspects of congressional membership—enacting policies and being re-elected—are difficult enough to juggle for each individual member. However, layered upon that is the reality that collective action is needed to pass a member’s policy goals and that the necessary collective action is much more likely to occur when the member’s party controls a majority of seats in the chamber. All members face these challenges, and one tool they have chosen to help manage them is to elect a leadership team for each party caucus.

Party leadership positions lack formal job descriptions, but I operate on the assumption that they involve carrying out two core goals that all congressional parties pursue: (1) to assist like-minded individuals in attaining election and re-election and (2) to facilitate the enactment of policies that reflect the preferences of party members and/or the party’s name brand.3See John Aldrich, Why Parties? (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1995).

Here, I aim to understand how party leaders manage competing party goals with a focus on trying to measure how “effective” certain party leaders are at the inherently difficult job of leading a congressional majority. I contend that the most effective parties will have leadership teams that can balance the pursuit of both goals simultaneously: making necessary tradeoffs to maximize policy reputation while minimizing electoral risk. The least effective leadership teams will push their caucus into too many electorally challenging votes or leave policies on the table that could have been enacted with no additional electoral harm to its membership. There are myriad ways to measure this but below I set out two standards by which to determine the effectiveness of party leaders: agenda success and control of the House floor.

Measuring a party’s policy success

At the outset of most Congresses, the party leadership lays out a set of legislative priorities they plan to enact during the timespan of the Congress. In some cases these are revealed as part of a large public relations campaign such as the Republican Party’s “Contract with America” that was publicized prior to the 1994 elections or the Democrats’ “Six for ’06’” campaign in advance of the 2006 elections. More typically, however, these priorities are presented in leadership speeches on the floor, interviews with reporters, or otherwise reported in the media. This measure thus evaluates the party on a scale set by the party itself, which likely reflects what the party leadership thought was both desirable and attainable given the political climate. To assess leadership effectiveness at enacting the party agenda I simply count the number of legislative priorities laid out by the party that were enacted in a given Congress divided by the number of priorities listed.4The method for finding party agenda times was adapted from the method used by Lee and Curry (2019) and involves coding leader statements, leadership bills numbers (typically HR 1–HR10), and articles in sources such as CQ Weekly, the New York Times, and the Washington Post. For simplicity, I code all items as either something being enacted consistent with the stated goal or not.

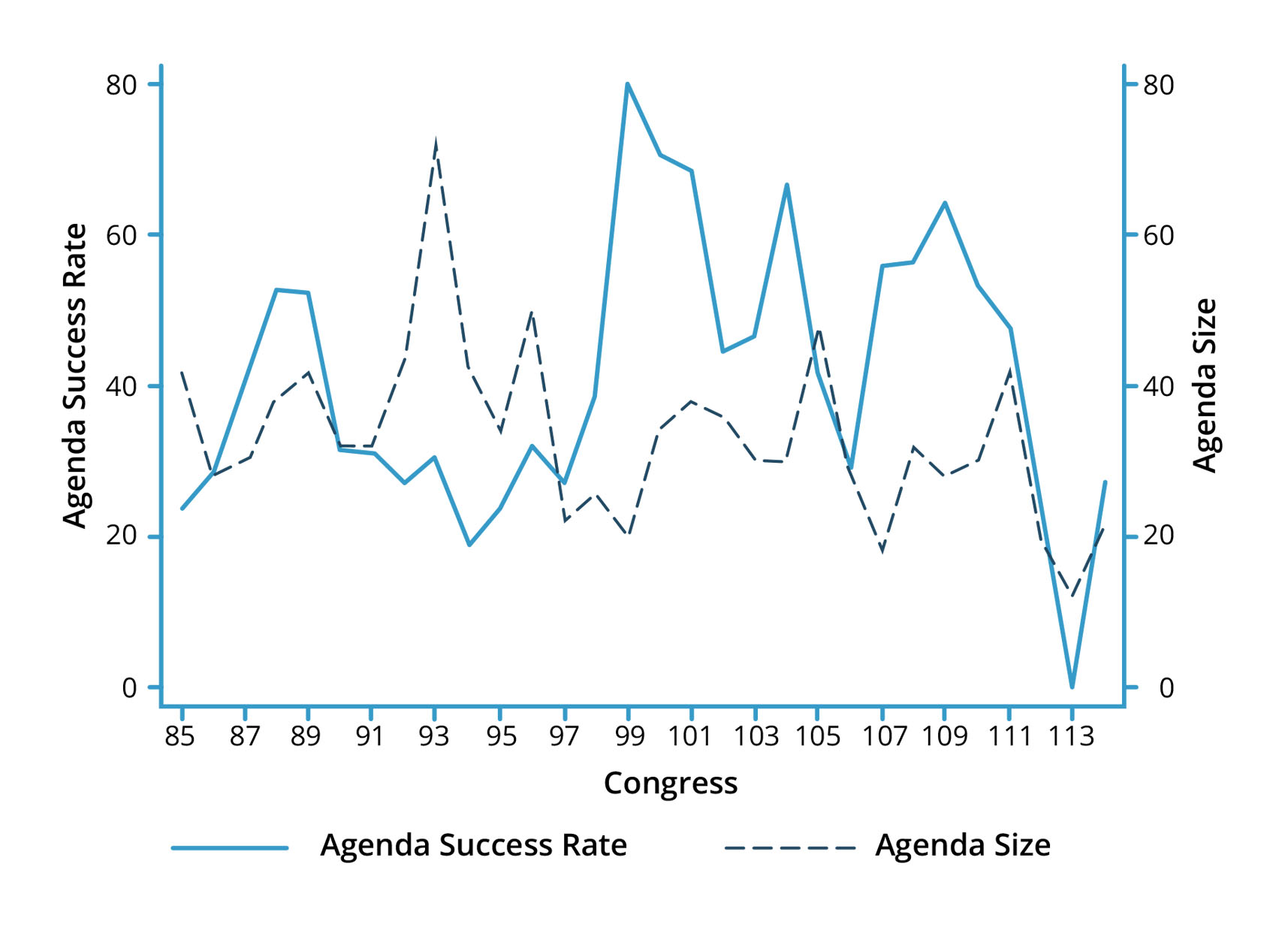

Figure 1 reports the size of the leadership agenda (number of items) and the enactment rate for the US House from the 85th to 114th Congresses, revealing considerable variation in both the size and success rate of agenda enactment. The average success rate is just over 40 percent and average size of the agenda is slightly more than 15 items per Congress. Interestingly, there is essentially no correlation (-0.01) between the size of the agenda and enactment success rate.

Figure 1. Party agenda size and success rate

It will come as no surprise to students of congressional history that the 88th and 89th Congresses had high success rates. Both had large Democratic majorities with a Democratic president and they enacted a host of major legislation, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the legislation creating Medicare and Medicaid. Both of these Congresses feature a consistent House leadership team with John McCormack of Massachusetts as Speaker, Carl Albert of Oklahoma as majority leader, and Hale Boggs of Louisiana as majority whip.

It will come as no surprise to students of congressional history that the 88th and 89th Congresses had high success rates. Both had large Democratic majorities with a Democratic president and they enacted a host of major legislation, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the legislation creating Medicare and Medicaid. Both of these Congresses feature a consistent House leadership team with John McCormack of Massachusetts as Speaker, Carl Albert of Oklahoma as majority leader, and Hale Boggs of Louisiana as majority whip.

However, the 99th and 100th Congresses also achieved high success rates. Both featured a Republican president (Reagan) and a Democratic House, while the 99th featured a split Congress, as Republicans controlled the Senate. During the 99th Congress, which was Tip O’Neill’s last as House Speaker, the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Balanced Budget Act and a major rewrite of the tax code were enacted. The 100th featured a fully Democratic Congress working with a lame-duck president who was weakened by scandal and serious losses in the 1986 midterm elections. The 100th Congress was Jim Wright’s first as House Speaker and saw Congress enact several major reauthorizations and an increase in federal sentences for drug crimes.

These examples illustrate that parties and leaders can achieve success in either unified or divided government. They do suggest that experience may be an important factor in leadership success. Speaker McCormack had been in the US House for more than 30 years by the time he became Speaker, while both Speaker O’Neill and Speaker Wright had served decades before becoming ascending to the top leadership post in the chamber.

Calculating “procedural misfires”

The second set of measures I used revolves around control of the House floor. The standing rules give the majority party considerable power over the floor agenda, and leaders can use these powers to shape the order of business in ways that benefit their party while disadvantaging the other side. Many things can go awry for the majority party. For example, a loss on a special rule or the previous question on a special rule indicates that the majority leadership has lost control of the floor agenda.5Special rules are simple resolutions that set the terms of debate for a bill before the House. Passage of special rule overrides the standing rules for how a bill is to be considering and allows the House to set a unique set of guidelines for each bill. Special rules are often used to limit the number or content of amendments to bills and dictate the amount of time allowed for debate on a bill. They serve as the major agenda-setting tool for the US House and are the primary means by which the majority party shapes the House agenda. Perhaps less consequentially, majority party defeats on the motion to recommit with instructions to report forthwith embarrass the majority and often force members to take positions on issues that they would rather avoid.6The motion to recommit is the penultimate stage of the bill consideration process in the US House. Importantly, the motion to recommit is reserved for members who are opposed to a bill, which in practice means the minority party. The motion to recommit with instructions to report forthwith serves as the last amendment offered to a bill. The minority party typically crafts this amendment in such a way that it is politically painful for some majority party members to vote against it.

Figure 2 highlights what I call “procedural misfires.”7These include losses on special rules and on the motion to recommit. Here the data reveal that majorities have become more efficient at managing the floor in recent congresses. It has been over a decade since the majority party lost an important roll call on an agenda-setting measure relating to a special rule. There is no doubt that there have been off-the-floor difficulties on this, but parties have managed to keep these from spilling onto the floor. Managing the floor was much more difficult in the earlier part of this data series, especially before Democratic Party reforms aligned the rules committee and the House leadership.

“Republicans have rarely lost a vote on the motion to recommit while in the majority, but Democrats routinely struggle with it.”Losses on the motion to recommit are not as consequential for the House majority as is losing control of a special rule, but they do highlight floor management difficulties. This motion is deeply vexing for House Democrats. Republicans have rarely lost a vote on the motion to recommit while in the majority, but Democrats routinely struggle with it. The 111th Congress stands out as Democrats lost more than 20 of these votes and the problem has recurred in the 116th Congress, as the new House majority has lost two of these. Interestingly, from the point of view of this project is that in the two recent failures, members have anonymously blamed the House leadership for failing to properly coordinate to defeat these motions. It is noteworthy that the top to Democratic House leaders (Speaker Pelosi and Majority Leader Steny Hoyer) are a constant across the recent motion to recommit difficulties, which suggests that dealing with this motion is a recurring weakness of their leadership team.

Figure 2. Procedural misfires in the US House

Conclusion

Leading a congressional majority is a herculean task. Modern leaders must be prodigious fundraisers, serve as the public face of their party, and attempt to manage a heterogeneous group of individuals who live in constant fear of losing their congressional seat. Decisions over whether to pursue a particular policy priority or not and how hard to push a vulnerable member to vote with the party often involve tradeoffs that put key party goals in conflict with one another. The decisions that leaders make on these and other issues affect major aspects of policy in the United States and abroad, while also affecting the career prospects of many rank-and-file members.

Given the immense difficulties involved in being an effective party leader, it stands to reason that there is considerable variance in the skillset of individuals chosen for these posts. The goal of this project is to try to systematically measure how well party leaders manage the multiple parts of this job. My hope is that by developing a set of indices that are comparable across leaders, I can identify the characteristics of effective party leaders. Much work remains, but the results I have to date suggest that experience in the chamber is a determinant of how effective party leaders are at certain aspects of the job.