Disaggregating the “99 percent”

Capitalism’s widening chasm between the ultra-rich and everyone else has emerged as a leading concern in American politics. Most notably, the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement formed in the wake of the financial crisis to voice loud opposition against the “1 percent” of Americans who plunder the economy at the expense of the “99 percent”: that is, the everyday people from a variety of class backgrounds who are increasingly burdened with exorbitant student debt, dim employment prospects, underwater mortgages, skimpy healthcare, and more. In 2015 Senator Bernie Sanders took up the “99 percent” narrative as the rhetorical centerpiece of his presidential primary campaign, speaking out against “elite” schemes to “rig” the economy.

“As a political rallying cry, ‘We are the 99 percent’ tells a particular story about race and capitalism, and how these forces intersect to produce economic inequalities.”As a political rallying cry, “We are the 99 percent” tells a particular story about race and capitalism, and how these forces intersect to produce economic inequalities. That story would suggest that oligarchy’s devastating consequences fall heaviest on the racially disadvantaged—especially black Americans—who therefore have the most to gain from mobilizing against the billionaires. Vox columnist German Lopez noted in 2016, after Sanders rejected black reparations, that he acknowledges the severity of racial inequality in the United States, but focused his campaign on fixing “economic inequality above all else.” Sanders, Lopez adds, “sees the fixes for economic inequality…as a way to also address racial inequality, since black communities are so often poor communities, too.”

On the other hand, the “99 Percent” narrative derives most of its emotional power from the perception that growing economic inequalities are decimating the once-vaunted American middle class, and therefore killing the American Dream. In other words, while this narrative acknowledges that racial minorities are more vulnerable to the devastation and upheaval that capitalism inevitably produces, it ultimately collapses racial difference into the broader project of holding the line against the attack on the middle class by elites.

What almost never comes up in this discussion is the uncomfortable truth that the American middle class is today, and has been since its very inception, disproportionately and overwhelmingly white. Due to longstanding overt and covert discrimination in housing and credit markets, black Americans are dramatically less likely than whites to own a home, and thus enjoy the generational benefits home ownership affords, which drives a stubborn racial wealth gap.1Laura Sullivan et al., The Racial Wealth Gap: Why Policy Matters (New York: Demos; Waltham, MA: Institute for Assets & Social Policy, Brandeis University, 2015). For these and other reasons, blacks never gained a solid foothold in the middle class.

Thus, to the extent that the middle class supposedly represents a vision of an American Dream that is economically inclusive of nonelites—a vision now increasingly under threat—it is worth remembering that this vision has been historically a racially exclusive one. In other words, while racism anchors the socioeconomic divide between the 1 percent from everyone else, it also fuels capitalism’s selective democratization, creating pathways of mobility and economic self-reliance for some within the 99 percent and not others. Drawing on W. E. B. Du Bois’s work on the Freedmen’s Bureau, this essay highlights how the democratization of American capitalism, seen through the lens of homeownership and economic self-reliance, is a racially stratifying force—and also for this same reason, a key battleground in the fight for racial justice.

Inclusive capitalism and the Freedmen’s Bureau

In The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois famously reflected that “to be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships.”2W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk ([1903], New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2007), 12. The remark showcases Du Bois’s fascination with understanding how capitalism works differently for whites than for blacks. By referencing the “land of dollars,” Du Bois calls up the American Dream of capitalism as a system of limitless wealth and economic mobility. Being black is therefore simultaneously a matter of racial and economic marginality: it is to feel chronically and hopelessly excluded from an economic mainstream that prides itself specifically on the virtues of being inclusive of and creating opportunity for people with limited financial means.

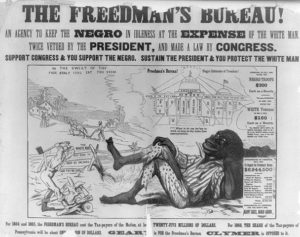

Du Bois, in later works, further explores the selective democratization of the capitalist economy, and how it creates racially exclusive pathways of economic mobility. This theme permeates his extensive treatment of the Freedmen’s Bureau, a government agency created to provide a support structure for black former slaves and white laborers in the wake of the Civil War. Du Bois spends much of his lengthy 1935 tome, Black Reconstruction in America, discussing the Bureau, which he called the “most extraordinary and far-reaching institution of social uplift that America has ever attempted.”3W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward A History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880([1935], New York, NY: The Free Press, 1998), 219.

The book’s analysis makes two key observations that together are essential to understanding the selective democratization of capitalism as a racially stratifying force. First, Du Bois’s historical findings highlight the reality that market economies are not self-regulating, and neither are market actors capable of economic self-reliance on their own. Instead, in capitalism, economic activities are politically managed to make self-reliance possible, enabling mobility for some groups (often whites) and not others. The Freedmen’s Bureau marked a rare exception and a curious natural experiment. It was created through the political mobilization of black Americans in the wake of the Civil War to facilitate their economic inclusion.

“The idea was that creating conditions of economic self-reliance required an extraordinary mobilization of resources and state power.”Du Bois repeatedly referred to the Bureau as a system of “economic guardianship,” where the federal government—more specifically the US Treasury Department—instituted a number of innovations to provide a support structure for former slaves. Through the support of the Bureau they could engage in private economic activities, including access to agencies and tools to secure labor contracts, purchase available cheap land, receive legal aid, and more. The idea was that creating conditions of economic self-reliance required an extraordinary mobilization of resources and state power.

Initially, the Bureau channeled most of its energy into the provision of food and clothes rations to tens of millions of “the hungry and unemployed.”4Du Bois, Black Reconstruction, 225. But the agency’s vision gradually shifted from poor relief (i.e., direct provision) to a more expansive retooling of capitalism’s financial machinery to facilitate the inclusion of former slaves. Rather than merely creating a separate lane of direct public provision for blacks, the Bureau aimed to explicitly democratize American capitalism to redress disparities between blacks and whites in their ability to participate in private economic activities in an ostensibly self-reliant way.

The second observation made by Du Bois is that the fiction of a “free” or “self-regulating” economy has proven a powerful ideological force, and one that sustained the discriminatory myth of white economic self-reliance.

From the start, the debate around the Bureau centered on a pressing question: for a historically oppressed black population, would abolition usher in an era of meaningful economic participation or just a hollow, surface-level form of inclusion? For example, black political leaders pushed for the confiscation and redistribution—and later the purchase and reselling—of land and property from white confederates and planters. They insisted that, given the profound “destitution of the freedmen…nothing would provide immediate relief like the redistribution of land.”5John Hope Franklin, “Public Welfare in the South During the Reconstruction Era, 1865–80,” The Social Service Review 44, no. 4 (1970): 379–392. In other words, meaningful black inclusion would require far-reaching governmental intervention to secure reparations and manage private exchange.

However, when freedpeople demanded “land—the famous forty acres and a mule—to provide an economic underpinning to their newly acquired freedom,” many whites insisted that such a demand “posed a threat to the sanctity of private property,” and that “blacks must acquire land by working for wages and slowly accumulating capital, like everyone else in a market society.”6Eric Foner, “Black Reconstruction: An Introduction,” The South Atlantic Quarterly 112, no. 3 (2013): 409–418. As Du Bois recounts, congressional leaders debated whether the Bureau itself was necessary to usher former slaves into economic freedom, or whether it would instead “curtail [the freedmen’s] ‘initiative and ‘self-reliance.’”7Du Bois, Black Reconstruction, 221.

This debate echoed what has become a familiar dialectic. On one side are those opposing government support for racial minorities on the basis that it undermines the virtues of economic self-reliance supposedly embodied by the capitalist economy. On the other side are those, like the freedpeople, insisting that government support is in fact constitutive of economic self-reliance—especially for whites, but also potentially for blacks. Du Bois viewed the Bureau as an exception that proved the rule: it illuminated how the reality of a politically managed economy works hand-in-hand with the fiction of a self-regulating one to democratize capitalism—i.e., make it inclusive of nonelites—for whites while simultaneously excluding blacks. The democratization of capitalism, in other words, is a racially stratifying force.

Indeed, as Du Bois chronicles in painstaking detail, the Bureau eventually collapsed under a firestorm of white backlash. While critics made rampant allegations of fraud and financial mismanagement on the part of Bureau, their real critique, as noted by Du Bois, attacked the very idea that blacks were worthy of economic guardianship. For example, Du Bois expressed incredulity at President Andrew Johnson’s remark that “Congress has never felt itself authorized to spend public money for renting homes for white people honestly toiling day and night, and it was never intended that freedmen should be fed, clothed, educated, and sheltered by the United States. The idea upon which slaves were assisted to freedom was that they become a self-sustaining population.”8Du Bois, Black Reconstruction, 276.

Du Bois attributed the intense opposition to the Bureau to what he referred to as the “American Assumption” that “wealth is mainly the result of its owner’s effort and that any average worker can by thrift become a capitalist.”9Du Bois, Black Reconstruction, 183. While white planters and white workers had long enjoyed a state-sanctioned system of economic support—from public bank charters; to the financing of services, infrastructure, and industry via public debt; to the expansion of the railroad system during the antebellum era—the creation of a Bureau to establish conditions of black self-reliance immediately aroused suspicion that blacks were getting a handout. As Du Bois recalled of Johnson’s comment, “it was the American assumption, of the possibility of labor’s achieving wealth, applied with a vengeance to landless slaves under caste conditions. The very strength of its logic was the weakness of its common sense.”10Du Bois, Black Reconstruction, 277.

Housing and the racial politics of affordability

By focusing on the backlash against the Bureau, Du Bois highlighted the importance of understanding capitalist democratization as a key battleground of racial contention, claims-making, and bottom-up movement-building. Anticipating ideas later popularized by political theorist Karl Polanyi, this perspective suggests that the “market economy” is not to be taken too seriously on its own ideological terms, but is better described as analogous to any other political arena—its structure and outcomes are molded by specific policies, practices, and institutions that emerge as a result of political agitation and resistance.11See Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time ([1944], New York: Beacon Press, 2001).

These insights continue to prove relevant for understanding racial capitalism today. In contemporary times, the democratization of capitalism can be seen in efforts to make life under capitalism—including essential goods and services—affordable to nonelites. Arguably the most important example is housing: in particular, the expansion of homeownership and its role in creating a predominately white American middle class. This extraordinary intervention made homeownership affordable, though almost exclusively for whites.

Prior to the New Deal, homeownership, in general, was so expensive that only the ultra-rich could afford it. Throughout the nineteenth century, for example, home credit remained scarce. The typical mortgage covered only one-third of the purchase price, carrying high interest rates and very short repayment periods. Consequently, “housing was…expensive in relation to the average family’s income and accumulated savings…[and] many people had to build their own houses by hand, become landlords for part of their property, and severely economize on basic private and public improvements to be able to afford owner occupancy.”12Marc A. Weiss, “Marketing and Financing Home Ownership: Mortgage Lending and Public Policy in the United States, 1918–1989,” Business and Economic History 18 (1989): 109–118. The housing shortages that resulted from this arrangement fueled growing social unrest, especially among working-class whites, including a “post-World War 1 wave of labor strikes.”13Weiss, “Marketing and Financing Home Ownership,” 109.

In response to this growing unrest, the federal government and the housing industry responded with an “Own Your Own Home” campaign in 1918. Federal officials introduced a slew of insurance subsidies and tax breaks, which ultimately became the basis of the modern 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage. By financing the development of large-scale residential subdivisions in the suburbs, the federal government played a leading role in making homeownership accessible to a growing, predominately white middle class, and opened a vast and lucrative new market for the private real estate and lending industries. This highly racialized democratization of home credit effectively transformed “the American suburb…from a rich man’s paradise into the normal expectation of the middle class.”14See Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987).

At the same time, black and Latinos were largely excluded from homeownership expansion. In the infamous practice of “redlining,” federal insurers deemed properties and neighborhoods occupied by racial minorities ineligible for mortgage investment, relegating the latter to rental slums or predatory mortgages. White homeowner groups waged violence against black residents who threatened take up residence in their communities. Meanwhile, the construction of the highway system created further distance between the affluence of white suburbia and the economic destitution of the black inner city.15See Douglas S. Massey and Nancy A. Denton, American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993).

In the face of such exclusion, blacks and Latinos pushed for political gains to make rental housing similarly affordable and secure. One example can be found in the Community Reinvestment movement.16See Gregory D. Squires, ed., From Redlining to Reinvestment: Community Responses to Urban Disinvestment (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992). This constellation of community-based groups emerged in the 1960s and 1970s at the tail end of the civil rights era. The movement achieved its most well-known political gain with the 1977 passage of the Community Reinvestment Act, which forced banks to expand their lending footprint within low-income and racial minority communities. Less well known, the movement also laid the groundwork for the use of tax credits to finance the production of housing for low-income renters, which eventually became the default national policy, replacing traditional federal programs like public housing.

“It is worth noting that movement leaders did not merely push for formal access to and representation within the housing market.”In some ways, Community Reinvestment advocates’ preoccupation with housing production and tax policy serves to illustrate how neoliberal themes of market innovation and entrepreneurial “self-help” have come to define contemporary policy agendas.17See Karen Ferguson, Top Down: The Ford Foundation, Black Power, and the Reinvention of Racial Liberalism (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013). Yet, it is worth noting that movement leaders did not merely push for formal access to and representation within the housing market. They mobilized to limit for-profit developers’ access to capital, create oversight boards with decision-making power over mortgage lending, and protest against contract selling, disinvestment, slum-lording, and loan-sharking in poor black and brown communities.18See Alexander von Hoffman, House by House, Block by Block: The Rebirth of America’s Urban Neighborhoods (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003).

In all of its political nuance, the Community Reinvestment movement powerfully illustrates the fraught racial politics of market affordability within American capitalism. Rather than embracing the American Dream narrative of a self-regulating market economy, its leaders sought to influence and expand the political management of housing markets on behalf of racial minorities by government officials. They openly contested the illusion of the market’s formal equality by vying for bottom-up control over the resources it circulated. In short, the Community Reinvestment movement envisioned the financial machinery of capitalism as part of the very terrain where issues of racial justice are fought out.

Conclusion

Efforts to dismantle and renegotiate the racially exclusive terms of inclusive capitalism live on in contemporary struggles around market affordability in housing, healthcare, education, credit, and other basic arenas of social life. The lesson of the Freedmen’s Bureau and Community Reinvestment is that the distinction between “politics” and “economy” is essentially a false one: the market economy is both politically constructed—and therefore subject to the same kinds of pressure tactics as formal politics—and also deeply enmeshed with the more explicitly political constructs of rights, representation, and state power. Community reinvestment advocates believed, like the freedpeople before them, that laissez-faire symbolism obscures the complex realities that define the political struggle to establish conditions for black economic self-reliance. As Du Bois’s writings attest, taking that symbolism too seriously can obscure capitalism’s selective democratization, which operates both as racially stratifying force, and also—for that same reason—a battleground in the fight for racial justice.

Banner photo credit: Seattle Municipal Archives/Flickr