Tides shape space, transcending both land and water. In Bengali, tidal spaces are known as bhatir desh (ebb-tide country). Yet, tides have no reference points in our cartographical imagination and in our histories. Tidal temporalities challenge our spatial fixities and confound the hard lines we draw between land and water. In an attempt to open a new space of scholarly practice that begins from the recursive motions of the tides and not from the comforts of a firm footing, I want to (1) explore not the possibility, but the impossibility of bringing tidal temporalities into the heart of viewing watery spaces; and (2) dwell with that impossibility in order to decolonize our visual literacy. Let us begin from the premise that a map-mindedness governs the visual framing of spaces. Yet, let us also remind ourselves that maps are not “transparent, uncontested encapsulations of a bounded [knowable] world, but performative assertions, entries into debates, points of reference for further elaboration.”1John Tresch, “Cosmologies Materialized: History of Science and History of Ideas,” in Rethinking Modern European Intellectual History, ed. Darrin M. McMahon and Samuel Moyn (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 163. They are artifacts of arguments and erasures of contested inhabitations. They are smooth spaces with land tapering off into water, creating two legal regimes and two separate practices of living in and with them.

“Can we turn to a mode of viewing and a reading practice of space that can gather together a multitude of inhabited worlds: rational, natural, and spiritual?”I am proposing that we view tidal spaces as sites of meshing and splitting of the quotidian, cosmological, and social hierarchies by exploring how these dynamics manifest on the tides of the Hooghly river in colonial Calcutta (now called Kolkata). A site of religious significance for caste Hindu Indians, the tidal river Hooghly surmounts the land-water binary of maps. Can we decolonize our map-minded approach to spaces in our research and pedagogy? Can we turn to a mode of viewing and a reading practice of space that can gather together a multitude of inhabited worlds: rational, natural, and spiritual? Bhati—or the amphibious blurring of land, silt, mud, and water—forces us to conceptualize a new visual literacy, to decolonize our representational and knowledge practices. And, at the same time, it also arrests any facile celebration of indigenous ways of knowing posited as a nationalist antidote against the violence of colonialism’s blinkered cartographies. It does not deliver us from the present to any precolonial, precartographic comforts of yore, but deposits us into the heart of the violence of hierarchies and organizes our contemporary representational entitlements.

Stationary cartography

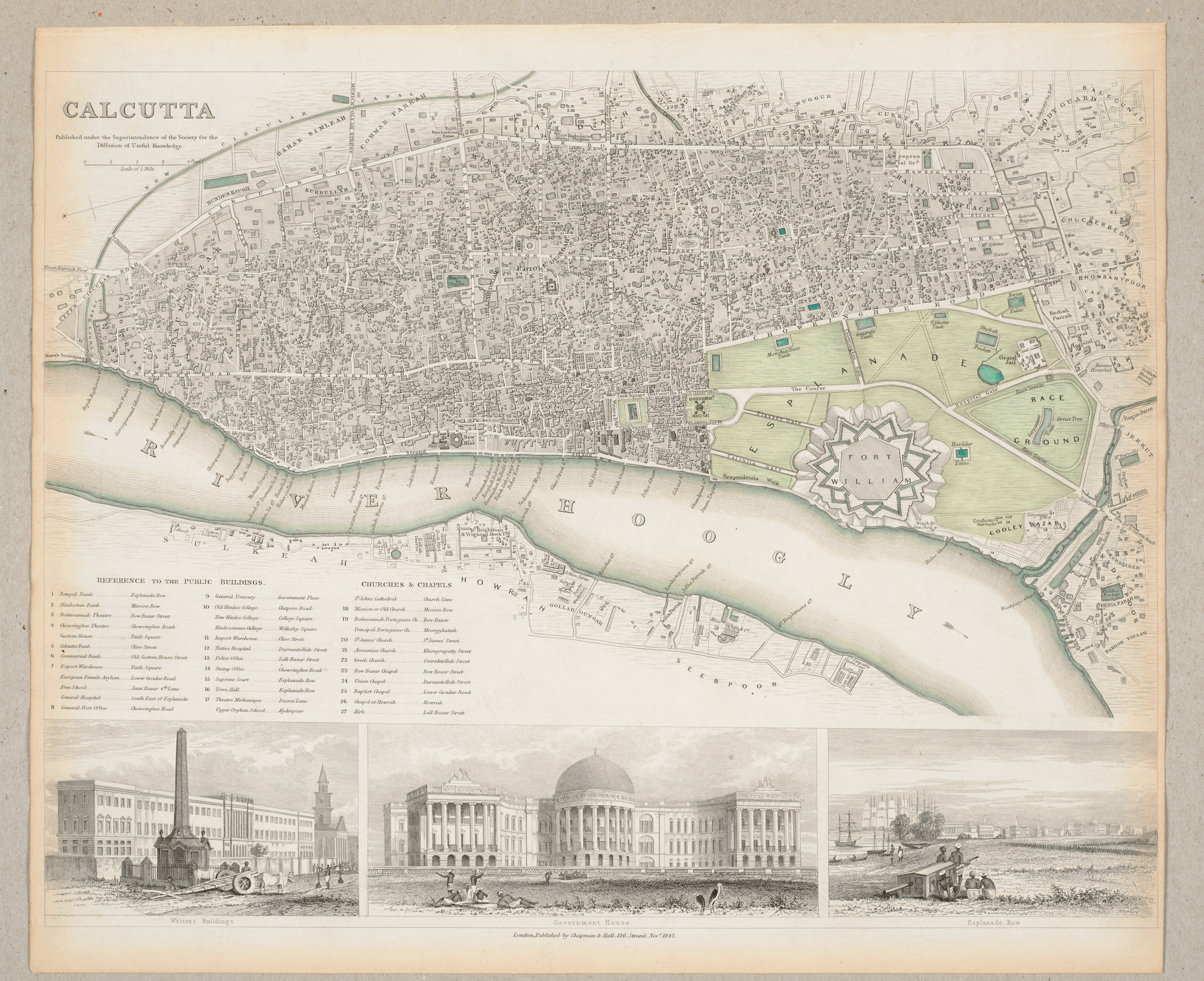

Titles order space through exclusions. Before I explain this new visual literacy, let us turn to two different colonial cartographic representations of the city of Calcutta and the river Hooghly that flanks it in the east. Let us pay close attention to the various seams, borders, and boundaries where tidal spatial imaginations untwine themselves. Figure 1, an 1842 map of Calcutta, is a classic visualization of urban landscape, the swamp-inundated Calcutta shaped by the tides of historical time and sedimentary deposits. We see how the Hooghly quietly flows; the neat green borders along its coasts hold little piers and docks, and the open green space marks its then southern boundary. Clusters of Indian and European homes are hedged in between two arterial roads, though housing has begun spilling beyond infrastructural borders. The neat circular canal on the north marks the end of the city as a white open space with no signs of life. The waters in this visualization are neatly flowing in more or less regular linearity, and in the process, trains our eyes to develop idioms to see bounded waters within the space of the urban.

But Figure 2, a 1790 map of the Hooghly, produced half a century before, depicts a slightly different river, whose edges are muddy. The waters spill out into creeks and depressions along its ways. This map captures a mobile space of sandbars, tidal sedimentations, and seasonal movements of land. The seasonality of lands, represented as dotted spaces, are missing in the 1842 map. The city has been fortified through infrastructures of the built environment and legal registers of land titles. The river is all we see in Figure 2, and traces of human habitation is coincidental, marked by the occasional building or temple. Dotted circular spaces show the impossibility of capturing in sketch either the river or its silt. The tides regularly flow into these spaces leaving behind a bog of knee-deep mud.

These two very different mapping practices should not be read as simply manifesting the progression of better cartographic technologies. What we should perhaps see in these are the repression of the tide countries—an erasure of the mobile landscapes that challenge mapping, and more importantly deeds, property laws, and the spatial practices that produce our built environment. If such maps and visual representations erase seasonality, temporality, and the tidal nature of moving land-water-scapes in this region, writing is no innocent activity either. How can writing and representation accomplish an attunement to the mobility of the landscape?

Fluid almanacs

“While almanacs endow place-time with verticality toward the astrological, atlas-based modern geographical representations freeze spaces in time and remain essentially horizontal.”I turn to almanacs as both a conceptual tool to interrupt the cartographic visual order and write spatial histories of water that are attuned to the ephemeral and the fleeting temporality of a tidal world.2I have explored this in greater detail in Empire and Ecology in the Bengal Delta: The Making of Calcutta (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), see especially Introduction and Chapter 3. Almanacs, based on the phases of the moon, traditionally documented days, seasons, movements of the sun, wind, and tides guiding the farmer, sailor, pastor, and a whole host of people in their trades. If premodern almanacs were geared toward the astrological, by the nineteenth century almanacs registered both clock-time and astrological-time. Two temporalities coexisted, since almanacs, unlike maps, are attuned to temporality in space, as the tides blurred land-water boundaries, and they were also attuned to time-space’s cosmological dimensions.3Alison A. Chapman, “Marking Time: Astrology, Almanacs, and English Protestantism,” Renaissance Quarterly 60, no. 4 (2007): 1257–1290. See especially her definition of verticality at 1271. While almanacs endow place-time with verticality toward the astrological, atlas-based modern geographical representations freeze spaces in time and remain essentially horizontal. That does not mean that almanacs are some kind of premodern, precolonial artifacts of viewing space.

Indeed, what I am proposing is in tune with Gautam Bhadra’s seminal work on almanacs in colonial Bengal. Bhadra’s work is grounded within the textual and iconographic world of nineteenth-century Bengali almanacs, which offers us important tools for reading historical temporality. In his rendition, historical temporality is far more complex than the radical convergence of overlapping or disjointed chronologies. He says they are but knots where multiple possibilities and many historicalities exist at one time.4Gautam Bhadra, “Pictures in Celestial and Worldly Time: Illustrations in Nineteenth-Century Bengali Almanacs,” in New Cultural Histories of India: Materiality and Practices, ed. Partha Chatterjee, Tapati Guha-Thakurta, and Bodhisattva Kar (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2014), 275–316. For a more in-depth treatment see Gautam Bhadra, Nyara Battala Jay Kaybar (Kolkata: Chhatim Books, 2011). This pushes us beyond singular histories of spaces to see other inhabitations, meaning-making practices, and unrealized multitudes knotted together in the movements of lands, water, and the meanings people attached to mobile landscapes. It turns our attention to the mud and bogs whose histories still remain to be robustly written.

In that spirit, let us turn to almanac as a visual lens. Almanacs record the flux of seasons and the cosmological movements of time through space. As an analytic, they operate by illuminating two lines of spatial thinking: a tidal temporality and a cosmological spatiality.

“For a tidal landscape like Bengal’s, maps are merely a snapshot in a much longer history of sedimentation.”Tidal temporalities are repetitive, yet unpredictable, movements of water, no matter how many tidal charts we prepare. Tides also pay little respect to human-drawn boundaries between river, land, water, and soil. Almanacs capture this temporality. Cartography, on the other hand, fixes in time moments in the movements of land and water. For instance, on a map, land and water appear as distinct entities separated by the hard lines of a coast or riverbank. For a tidal landscape like Bengal’s, maps are merely a snapshot in a much longer history of sedimentation. Cartographic techniques fail to depict the temporality that defines land-water relations in the Bengal delta, which exceed the strict lines of cartographic boundaries, where inhabited marshes, wetlands, mangroves appear as blank blue blobs without traces of the lives, dreams, and aspirations infused in them. Applying a recurrent-tidal logic to the spatial then helps recover river-water relations, which exceed the bounds of modern geographical understanding to reveal the limits of cartographic representations of space. Dwelling with the tidal movements makes us aware of their lunar aspect—the cosmological and astrological meaning-making practices that are woven into these movements.

Photo credit: Debjani Bhattacharyya.

Toward almanac thinking

Almanac then helps us understand Calcutta and the Hooghly not simply as a colonial city, but recover a world where riverine spirits and ancestral deities splice the mundane strands of colonial bureaucracy together.5For more detailed analysis of riverine deities and colonial judiciary see my “Notarizing Possession,” Empire and Ecology in the Bengal Delta. Bhadra’s work on Bengal and Alison Chapman’s work on English almanacs attest to the much-overlooked world of these almanacs, which register a traffic between the cosmological, astrological, and the early-modern spirit. As Bhadra shows, the celestial and imperial chronologies are both present in the logic of reticulation that structures the temporal order of the almanac.6Bhadra, “Pictures in a Celestial and Worldly Time,” 281.

Given that the river Hooghly is considered holy by the Hindu population, and is used as a site for ablutions, cremations, and is dotted with small and large temple complexes, the banks of the river, its tides and the muddy space between land and water are located within multiple registers of meaning. What I am proposing is not simply maps as an object of colonial rationality opposed to an enchanted amphibious autochthony. Rather, subverting notions of colonial difference and native enchantment, we encounter cosmological worlds where river spirits jostle with seasonal traders, colonial officials, planners, and pilgrims knotting together multiple ways of inhabiting a cosmological ecology. Almanacs, attuned to the temporalities of tides, therefore hold the spatio-temporal tension between repetition and difference.

“Thinking through the almanac also opens us to new ways of reading space beyond the colonized intervention and precolonial romanticism.”Thinking through the almanac also opens us to new ways of reading space beyond the colonized intervention and precolonial romanticism. For instance, before the arrival of Europeans, the populations living in the villages and marshes which became Calcutta dug or widened canals for navigation. These populations moved with the fish and lived with the ebb and flow of the water. How do we understand and read those interventions into the landscape? They have left few archival records except for brief anecdotes and songs.7One of the few published collections of fishermen songs, riddles and anecdotes about life in Calcutta before British arrival is in Dnere, Samajik O Rajnaitik Prekhapete Jele Kaibarta (Kolkata: Offbeat Publishing, 2006), 244–76. However, traces of these anthropogenic canals have been sedimented in the naming of the city, such as Creek Row, a central street in Calcutta purported to be on top of a disappeared man-made canal. The same applies to Ultadanga, a Calcutta neighborhood whose name signals dry land close to the river.8The affix danga comes from the Bengali word meaning dry land. I have explored the various connotations of place names as sites for environmental history of the city in Debjani Bhattacharyya, “Geography’s Myth: The Many Origins of Calcutta” in Unarchived Histories: The “Mad” and the “Trifling” in the Colonial and Postcolonial World, ed. Gyanendra Pandey (London: Routledge, 2013), 146. For a reading of the names of the various neighborhoods and the ecological past they attest see, A. K. Ray, A Short History of Calcutta, Town and Suburbs (Calcutta: Rddhi India, 1982), 4.

Mobilizing an almanac mode of reading takes the challenge posed by a moving landscape to think beyond atlas-based frameworks that define much of our modern geographical knowledge and, by default, our legal understanding of places. Spatial histories have much to gain by moving away from atlas-thinking to almanac-thinking. Such a shift will question the grounds upon which our understandings of law, the market, and design have solidified and confront us with the forms of collective amnesia that continue to bolster these understandings.

Banner photo: William Prinsep, The Nizaamat Qila (Criminal Court) of the Nawab of Bengal along the banks of the Hooghly River, 1840, 22.4 x 43.6 cm, British Library.