“The ocean floor is an interminable desert of grayish ooze,” The Sunday Oregonian informed its readers in 1913. Of the many dreadful creatures known to live along the sea bottom was the black swallower, an animal thought to be “chiefly mouth, [which] spends its time buried in the ooze, waiting for a victim to come along.”1“Sea Serpents: They Are a Reality and Not a Myth,” The Sunday Oregonian, August 24, 1913, Historic Oregon Newspapers. Beware, the newspaper cautioned, of the gray, goopy mysteries that blanketed the bottom of the sea.

The Sunday Oregonian’s preoccupation with the ocean bottom was not unique. Vivid descriptions of the seafloor stretched back decades as, year after year, US newspapers told tales of the ocean’s depths. In 1862, as the Civil War ravaged the country, the Weekly Colusa Sun distracted its readers with a description of a foreign, watery world. “The whole floor of the Atlantic is paved with a soft, sticky substance, called ooze, mostly consisting of minute animals, many of them mere lumps of jelly, and thousands of which could float with ease in a drop of water, some resembling toothed wheels, others bundles of spines or threads shooting from a little globule.”2“Below the Atlantic,” Weekly Colusa Sun 1, no. 23 (June 7, 1862), California Digital Newspaper Collection.

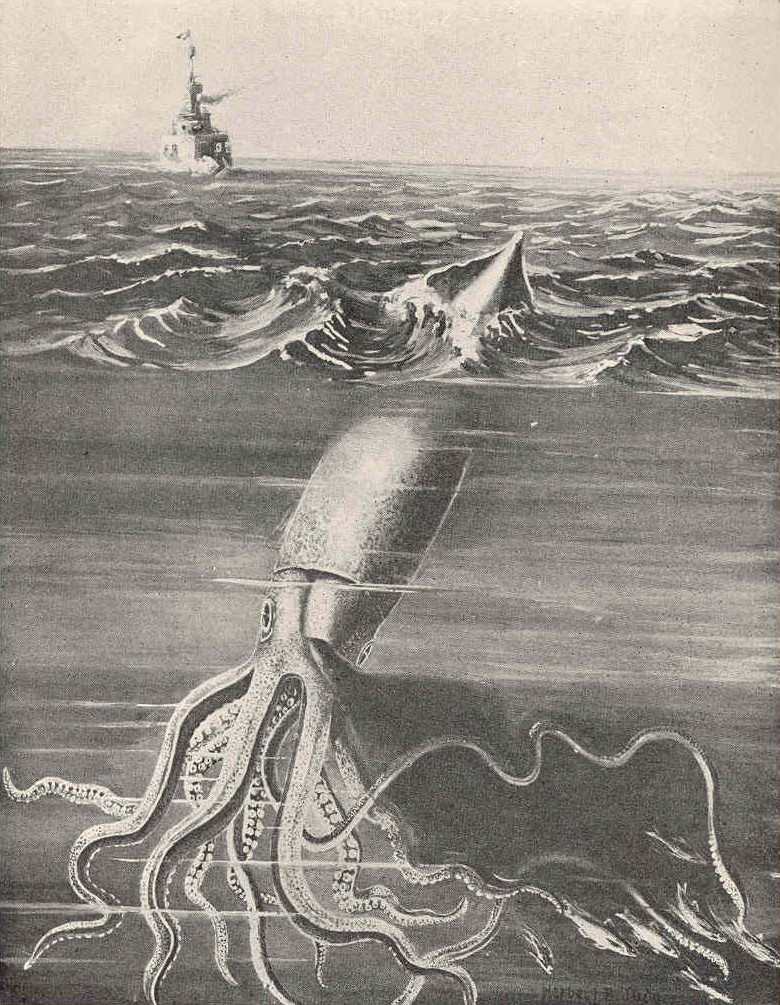

Glance at almost any publication on the marine environment written before the mid-twentieth century, and the chances are good that you will find a reference to ooze. A sticky, gooey, muddy substance, ooze resulted from marine organisms that had died and fallen from the surface of the water to the bottom, where they decomposed. Ooze represented more than just a seafloor sediment, however. It was the kind of substance that could drip from the tentacles of a giant squid, enrapturing generations of Americans who had only dreamed of knowing what scary secrets existed within the deep blue sea.

It’s been a century since ooze reached its heyday in US publications, but I cannot stop thinking about it. My obsession with ooze is due, in part, to my career choice. As a marine environmental historian, I spend my time reading historical accounts of the sea. My research is part of a growing field of scholars who want to understand how people interacted with the ocean in the past. What kinds of boats or submarines or tools did they invent to pierce its depths? What and where did they fish? Did they dream of the deep sea like they dreamed of outer space? What kind of scientific knowledge have people held about the ocean at any particular period in time?

There’s a critical reason that historians want to answer these questions about the sea. In the present day, our global society is utterly dependent on the ocean—its surface, water column, and seafloor—for the great variety of resources and environmental functions that it provides. Just think of the fish on your dinner plate, the gas in your car, the email that zipped through submarine cables to arrive seamlessly in your inbox, the sand and gravel mixed into the concrete sidewalk, or the precious metals tucked into your cell phone. Our dependence on and knowledge of the ocean is the result of a long historical process that included many decades of discovery, trial and error, imagination, colonization, and environmental alteration.

Seafloor ooze is just one small component in the larger story of marine environmental history, but it’s an alluring one.

Ooze and marine exploration

Before the nineteenth century, knowledge about the creatures and materials that existed on the deep seafloor was negligible. By the mid-1800s, however, the deeper seabed was receiving a great deal of attention, thanks in part to the development of new technologies that allowed naturalists and sailors to better access the deepest reaches of the earth. Innovations in steam-powered ships, improved tools to more accurately measure the ocean’s depths, and the invention of submarine telegraph cables made knowledge about the deep sea not only more accessible, but also more important.3See Helen Rozwadowski, “Fathoming the Fathomless,” chap. 1 in Fathoming the Ocean: The Discovery and Exploration of the Deep Sea (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005). Would ooze damage the sheathing that protected telegraph cables? Could creatures exist thousands of feet below, or did the ocean’s pressure squish them? And if the pressure squished marine life, would it also destroy delicate instruments? Were there mountain ranges along the seafloor that might impede the path of a transoceanic cable?

As the long nineteenth century progressed, a hodgepodge of naturalists, sailors, industrialists, and sea captains began to piece together what life must be like on the deep seafloor. And ooze was never far out of mind—were there different types of oozes? Did it exist across the entire breadth of the ocean bottom?

A series of ocean-going expeditions during the second half of the nineteenth century verified the widespread existence of seafloor ooze. One of those expeditions was the HMS Challenger, which sailed from 1872 to 1876. The Challenger travelled nearly 69,000 miles and, among many other experiments, collected samples of the deep seafloor at hundreds of locations across the ocean basins. To acquire samples of the seabed, the crew would drop a dredge over the side and let it fall to the bottom. Attached to the vessel by a long rope, the dredge would slide across the seafloor and scoop up sediment. Once retrieved from the bottom, scientists on board studied the samples under a microscope. The Challenger expedition verified that multiple types of oozes covered great swaths of the seafloor.4→Tony Koslow, The Silent Deep: The Discovery, Ecology and Conservation of the Deep Sea (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2007), 30.

→Robert Kunzig, Mapping the Deep: The Extraordinary Story of Ocean Science (New York: W. W. Norton, 2000), 93–94.

→For the Challenger’s findings, see F. Tourle Thomson, G. S. (George Strong) Nares, J. Murray, and Charles Wyville Thomson, Report on the scientific results of the voyage of H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873–76 under the command of Captain George S. Nares … and the late Captain Frank Tourle Thomson, R.N. (Edinburgh: Printed for H.M. Stationery Office, 1880–95).

Ooze turned out to be of great interest to submarine cable-layers, too. Whereas some engineers initially worried that ooze might corrode telegraph cables, by the second half of the nineteenth century it was clear that ooze and cables partnered well together. One famous telegraph engineer, Charles Bright, wrote with excitement when a proposed cable route across the Mediterranean was discovered to have “an excellent bottom of soft ooze.”5Charles Bright, Submarine Telegraphs: Their History, Construction, and Working (London: Crosby, Lockwood, and Son, 1898), 68. The ooze promised a squishy blanket on which the cable could rest, unmolested by the rough corals, rocks, or swift currents that threatened cables in other areas of the seafloor. The detection of ooze on the seabed provided a sigh of relief for any cable-layer, no matter the ocean basin.

With the findings of the Challenger and other scientific expeditions shared widely around the world, and with telegraph submarine cables crossing many of the oceans by the early twentieth century, fact and fiction united to uncover a sea bottom that fascinated the public.

Ooze and the popular imagination

As scientific expeditions made an increasing number of marine discoveries, the US public in particular developed a growing curiosity about the ocean. In droves, they leisured at the seashore, collected specimens along the beach, and read about the ocean’s murky depths.6See Rozwadowski, Fathoming the Ocean and Gary Kroll, America’s Ocean Wilderness: A Cultural History of Twentieth-Century Exploration (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2008). As historian Gary Kroll has explained, Americans viewed the ocean as the next great “frontier wilderness.”7Kroll, America’s Ocean Wilderness, 2. Like the frigid South Pole of Antarctica, the arid plains of the Wild West, or the infinite expanse of outer space, many Americans threw their enthusiasm behind the exploration of the frontier. The sea was no different. The ocean’s sticky seafloor was an untamed wilderness, its proximity closer than the moon yet its depths still utterly alien.8Stefan Helmreich, Alien Ocean: Anthropological Voyages in Microbial Seas (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2009) 14–15. The average person may never get a chance to descend into the deep blue, but it was still worth the fantasy. As one of the ocean’s most insidious substances, ooze helped to create an image of the sea that was equal parts terrifying and thrilling.

Alongside newspapers and scientific reports, science fiction writers made ooze a household term. There is no better example than Jules Verne’s popular book, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, first published in 1870. In the novel, three unsuspecting characters are taken captive aboard the Nautilus, a submarine led by the intrepid Captain Nemo. On the Nautilus, readers journey along with the three captives as they discover an undersea world. In chapter 16, while walking along the seafloor in a diving suit, Professor Pierre Aronnax noticed that “the nature of the seafloor changed. The plains of sand were followed by a bed of that viscous slime Americans call ‘ooze,’ which is composed exclusively of seashells rich in limestone or silica.”9Jules Verne, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, trans. F. P. Walter (Paris, France: Hetzel, 1870), Part 1, Chapter 16, accessed online through the Educational Technology Clearinghouse, University of South Florida. Americans liked their ooze.

Ooze still persists in the public imagination in present day, although to a lesser degree. The widely popular card game, Magic: The Gathering, has a “biogenic ooze” card. On it is a painting of the “green Ooze monster,” which looks like a cross between an octopus and Flubber. Even in the twenty-first century, ooze can still evoke the image of a deep-sea creature smelling of sulfur and dripping wet with putrid sludge.

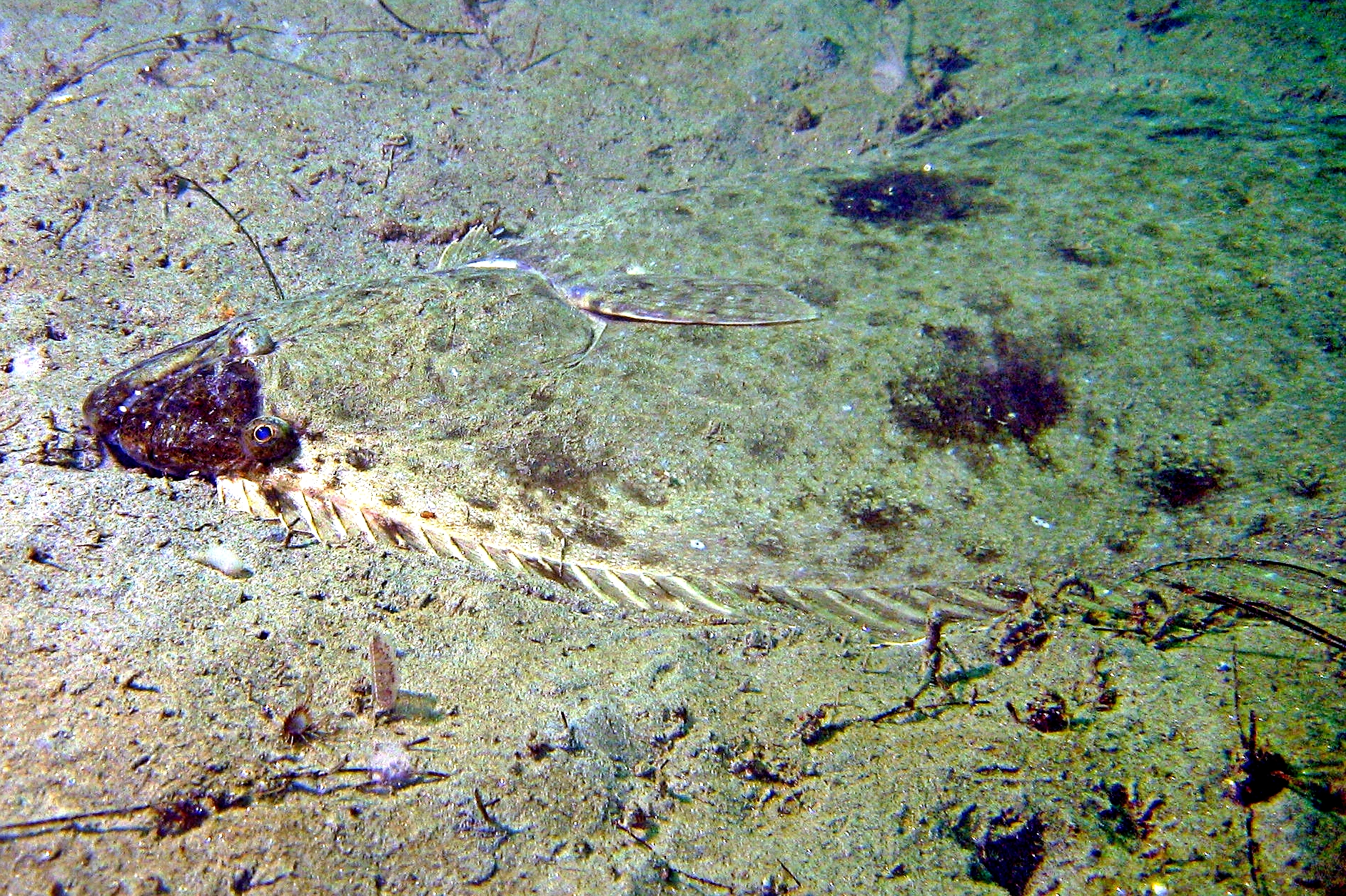

In modern marine science texts, ooze does not receive the same type of embellished descriptions that appeared a century ago. Nowadays, ooze is more formally called microscopic biogenous sediment (it’s also referred to as biogenic ooze or biogenic sediment) meaning “derived from organisms.” Scientists have long understood that ooze is the result of tiny sea creatures that have died, their shells floating slowly to the bottom of the ocean. Under the pressure of many fathoms of seawater, the skeletal remains compress and combine with other sediments, such as clay, to eventually produce ooze. To be formally classified as ooze rather than another type of seafloor sediment, it must contain at least 30 percent of these biogenous shell remains. The ooze is further subclassified depending on which type of microscopic organisms predominate.10→Alan P. Trujillo and Harold V. Thurman, Essentials of Oceanography (Pearson, 2020), 114, 117–118, 121, 133.

→Encyclopedia Britannica, s. v. “ooze,” accessed April 1, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/science/ooze.

Biogenous sediment is most likely to exist on the deep seabed where there is high productivity at the surface of the water. In other words, the more microscopic organisms that live in a particular region of the ocean, the more likely they are to die and accumulate at the bottom, resulting in thick layers of ooze. Some regions of the ocean have far fewer organisms, which explains why ooze does not exist in equal quantities across the seafloor. One type of ooze, called calcareous ooze, covers almost half the ocean’s seabed.11Trujillo and Thurman, Essentials of Oceanography, 114, 117–118, 121. As it turns out, ooze is quite common.

And what, exactly, does ooze feel like? As two scientists recently described it, “Ooze has the consistency of toothpaste mixed about half and half with water.”12Ibid., 14.

Besides its role on the seafloor, part of ooze’s appeal is in the function of the word itself. Ooze works as an adjective, noun, and verb (the ooziest ooze oozes).13English-speakers have used the term “ooze” for many hundreds of years, originally deriving from the Middle English word “wose” meaning “juice.” By the mid-sixteenth century, ooze had shifted to the spelling and pronunciation with which we are now familiar. According to a search of all English-language publications available on Google Books, authors most widely employed “ooze” between 1860 and 1950, its usage peaking during the 1870s. These oozy years coincided with an explosion of both scientific and popular literature about the ocean. See Merriam Webster, s. v. “Ooze,” accessed April 1, 2020, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ooze; Google Books Ngram Viewer, s. v. “Ooze,” accessed April 1, 2020. In this same period, the term “ooze” also commonly referred to leather tanned with “An infusion of oak bark or other vegetable matter,” see Lexico, s.v. “Ooze,” accessed April 1, 2020, https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/ooze. For me, ooze is especially fascinating because it has no equivalent substance on land. Ooze is a salty death goo unique to the seafloor, a tangible representation of an alien world that continues to beckon further exploration. Ooze evokes a reaction of both ick and allure, symbolic of how many of us view the ocean’s other creatures, depths, and features.14See Helmreich, Alien Ocean.

References:

→Robert Kunzig, Mapping the Deep: The Extraordinary Story of Ocean Science (New York: W. W. Norton, 2000), 93–94.

→For the Challenger’s findings, see F. Tourle Thomson, G. S. (George Strong) Nares, J. Murray, and Charles Wyville Thomson, Report on the scientific results of the voyage of H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873–76 under the command of Captain George S. Nares … and the late Captain Frank Tourle Thomson, R.N. (Edinburgh: Printed for H.M. Stationery Office, 1880–95).

→Encyclopedia Britannica, s. v. “ooze,” accessed April 1, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/science/ooze.