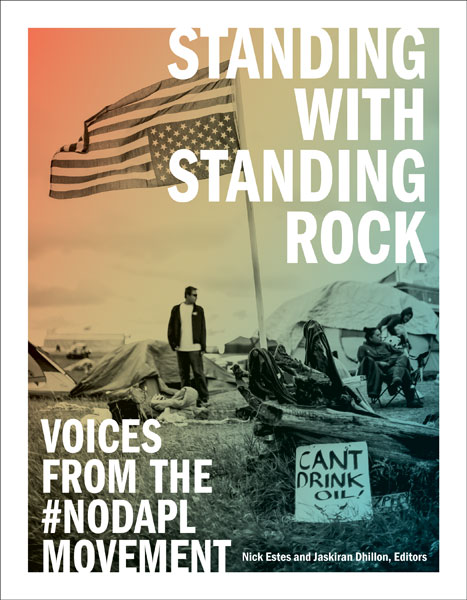

Water’s nature is diasporic. It transits and carries and adapts to environments whether engineered, neglected, or carefully preserved. Often, it misbehaves in such a way that reminds humans of the limits of their own power and control.1Andrea Ballestero argues that water, because it “often confounds any attempt at fixity.” A Future History of Water (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 13. Some humans, theorists suggest, are more attuned to those lessons than others. In particular, those who live and think at the shore, where the boundary between land and water is so often muddied that terrestrial principles of Western private property regimes feel like fictions, can easily understand how indebted we are to waterways. “Water is Life!” goes the urgent refrain, though it should not have to bear so much repeating.2 The University of Minnesota Press, 2019More Info →

The University of Minnesota Press, 2019More Info →

The diasporic shallows

Black and Pacific studies scholarship lingers where waters and dirts meet. Shoals, wakes, tidalectics, and muliwai operate as more-than-metaphors for articulating the limits of state power for variously racialized Indigenous peoples.3→Tiffany Lebatho King, The Black Shoals (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019).

→Christina Sharpe, In the Wake (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).

→Kamau Brathwaite, The Arrivants (Oxford University Press, 1973).

→Manulani Aluli Meyer, Hoʻoulu (Honolulu, Hawaiʻi: ʻAi Pōhaku Press, 2003). Frequently coded as Black and brown, these interstitial spaces underpin theories of not only liminality, but also adaptation, flow, and interconnection.4→Epeli Hauʻofa, “Our Sea of Islands” in A New Oceania: Rediscovering Our Sea of Islands, eds. Eric Waddell, Vijay Naidu, and Epeli Hauʻofa (Suva, Fiji : School of Social and Economic Development, The University of the South Pacific, 1993).

→Vicente M. Diaz, “Voyaging for Anti-Colonial Recovery: Austronesian Seafaring, Achipelagic Rethinking, and the Re-mapping of Indigeneity,” Pacific Asia Inquiry 2, no. 1 (2011). Shorelines, indeed, do much to trouble the neat boundaries, borders, and blood quantums of the colonial imaginary, compelling Tiffany Lethabo King to “offer the space of the shoal as simultaneously land and sea to fracture this notion that Black diaspora studies is overdetermined by rootlessness and only metaphorized by water and to disrupt the idea that Indigenous studies is solely rooted and fixed in imaginaries of land as territory.”5King, The Black Shoals, 4. Imperialism’s historical weddedness to land as the essential, irreducible element of desire (in the words of Patrick Wolfe), produced conditions of estrangement and displacement for peoples who were deemed either an obstruction to, or necessary for, capitalist extraction.6Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006): 388. In that sense, the logics of elimination inflicted upon Indigenous peoples of the Americas worked in tandem to the logics of proliferation fixed upon enslaved peoples forced across the Atlantic. Christina Sharpe tells us that “living in/the wake of slavery is living ‘the afterlife of property’,” gesturing at once to the containment logics that have structured settler-capitalism, but also the shallows carved into those wakes, in which care becomes the praxis of survival.7Christina Sharpe, In the Wake, 15. Wading in the shallows long enough makes apparent that the shallows is not a place, but a temporal condition of submerging and surfacing through water. Both fertile and capricious, the shore holds possibilities for reconciling the terrestrial violence of Indigenous dispossession against the oceanic transport of racialized labor needed to monocrop stolen lands.8King, The Black Shoals.

And so thinking about shallows necessitates attention to the multiplicity of water, and the ways that tides, rivers, storm clouds, tide pools, and aquifers converse with the ocean to produce what scholars have variously termed sea ontologies, wet ontologies, or archipelagic thinking.9→Elizabeth DeLoughrey, “Submarine Futures of the Anthropocene,” Comparative Literature 69, no. 1 (2017): 32–44.

→Philip Steinberg and Kimberley Peters, “Wet Ontologies, Fluid Spaces: Giving Depth to Volume Through Oceanic Thinking,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 33, no. 2 (2015): 247–264.

→Craig Santos Perez, “Guam and Archipelagic American Studies,” in Archipelagic American Studies, eds. Brian Russell Roberts and Michelle Ann Stevens (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017). For Kanaka Maoli, the muliwai, or estuary, best theorizes shoreline dynamics: It is not only where land and water mix, but also where different kinds of waters mix. Sea and river water mingle together to produce the brackish conditions that tenderly support certain plant and aquatic lives. It also informs approaches to aloha ʻāina, a Native Hawaiian place-based praxis of care.10I am inspired here by the philosophy of Manulani Aluli Meyer, Hoʻoulu: Our Time of Becoming (Honolulu: ʻAi Pōhaku Press, 2004). As Philipp Schorch and Noelle M.K.Y. Kahanu explain,

the muliwai ebbs and flows with the tide, changing shape and form daily and seasonally. In metaphorical terms, the muliwai is a location and state of dissonance where and when two potentially disharmonious elements meet, but it is not “a space in between,” rather, it is its own space, a territory unique in each circumstance, depending the size and strength or a recent hard rain.11Philipp Schorch and Noelle M.K.Y. Kahanu, “Forum as Laboratory: The Cross-Cultural Infrastructure of Ethnographic Knowledge and Material Potentialities,” in Prinzip Labor: Museumexperimente im Humboldt Lab Dahlem (Nicolai: Berlin, 2015), 246.

To refine their description for the purposes of my argument here, the muliwai might be better characterized not as a space, but instead as a conditional state that undoes territorial logics. Muliwai expand and contract; withhold and deluge; nurture and sweep clean. It is not a space of exception. Rather, it is where we are reminded that places are never fixed or pure or static. Chamorro poet Craig Santos Perez reminds us in his critique of US territorialism that “territorialities are shifting currents, not irreducible elements.”12Craig Santos Perez, “Transterritorial Currents and the Imperial Terripelago,” American Quarterly 67, no. 3 (2015): 620. If fixity and containment limit, by design, how futures might be imagined beyond property, then the muliwai envisions decolonial spaces as ones of tenderness, care, and interdependence.13I draw here from Robert Nichols, Theft is Property! Dispossession and Critical Theory (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019).

Tidal relations

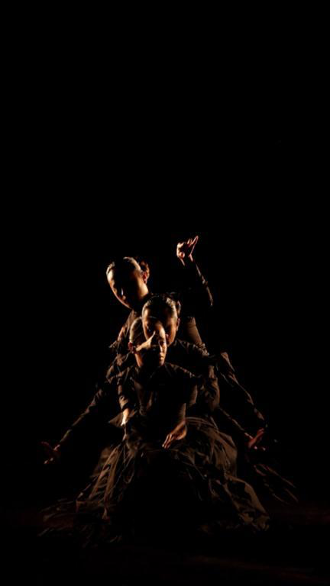

Across time, but particularly in recent decades, performance and literary works produced by Pacific Islander artists recognize water as an agential being, and as a being with whom we are in relation, that can be dialogically engaged. I have written about some of these works elsewhere, particularly Shigeyuki Kihara’s Siva in Motion (2012) and Kalisolaite ‘Uhila’s Ongo Mei Moana (2015)—performance art pieces that variously question what happens when oceanic intimacies are troubled by unusual and potentially violent behaviors, like tsunamis and king tides.14Hi’ilei Julia Hobart, “when we dance the ocean, does it hear us?” Journal of Transnational American Studies 10, no. 1 (2019): 187–192. For Kihara, her alter ego Salome dances a siva in response to a 2009 tsunami that devastated Samoa.15Siva refers to a style of traditional Samoan dance generally and also often references a particular style of dance called the taualuga, which often marks the culmination of a dance performance. See Jennifer Radakovich, “Movement Characteristics of Three Samoan Dance Types: Māʻuluʻulu, Sāsā, and Taualuga.” (master’s thesis, University of Hawaiʻi, 2004). As her gestures compound upon one another like delicate waves, they connect the relentless building of tsunami waves to the onslaught of colonialism represented by the nineteenth century mourning dress that binds her body. Similary, ‘Uhila, dressed in a traditional Tongan girdle of ngatu and si leaves uses dance to “conduct” the ocean’s tides by calling them in, while the water, choppy and grinding, surges toward the commercial waterfront of Wellington, New Zealand, as a symbol of global capitalism’s infringement on Pasifika space.

Below the surface of these urgent works simmers a lingering discomfort with an ocean that increasingly threatens human life. The collaborative video poem “Rise: From One Island to Another,” (2018) created by Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner and Aka Niviâna as a response to shared threats of climate-induced displacement between their respective homelands of the Marshall Islands and Greenland, addresses how environmental change across the globe binds Indigenous islanders together into a kind of shared risk: the care that fills a wake’s hollow.16Ashanté Reese, “Refusal as Care Ethnography from Elsewhere,” Anthropology News blog, June 4, 2019, drawing on Christina Sharpe, “And to Survive,” Small Axe 22, no. 3 (2018): 171¬–180. As an example within, the video poem crescendos when Jetñil-Kijiner and Niviâna face each other atop a glacier with gifts of shell and stone. Surrounded by the forced alienation of island and sea, these gifts reflect resolve in oceans of uncertainty. These gestures foreground the embodied relationship that humans have with their environments by recognizing how our bodies exist intimately and interdependently within the material world.17→Mary Phillips, “Developing Ecofeminist Corporeality: Writing the Body as Activist Poets,” in Contemporary Perspectives in Ecofeminism, eds. Mary Phillips and Nick Rumens (London: Routledge, 2016).

→Stacy Alaimo “Trans-Corporeal Feminisms and the Ethical Space of Nature,” in Material Feminisms, eds. Stacy Alaimo and Susan J. Hekman (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008). To take this concept further, “Rise” grounds ecofeminist activism and poetics in specifically Indigenous epistemologies and ontologies that bind together environment, deep time, and relationality: expansive ways of being in the world that exceed territoriality.

While these artistic examples here are limited to the context from which I, a Pacific Islander, write, it bears noting that there are many other Indigenous cultures that maintain intimate relations with animate bodies of water.18See Julie Cruikshank, Do Glaciers Listen? Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2005); Jen Rose Smith, “Indeterminate Natures: Race and Indigeneities in Ice-Geographies” (PhD diss., University of California at Berkeley, 2018); and Maurya Wickstrom’s “Wet Ontology, Moby-Dick, and the Oceanic in Performance,” Theatre Journal 71, no. 4 (2019): 475–491. This translates into both a genealogical history and a politics of the future, in that we might see Indigenous relationships with the nonhuman drawing upon deep historical knowledges in order to envision decolonial futures. Water’s interpellation as person (or, more precisely, as being) helps us, then, to better define the limits of an anthropocentrically oriented Anthropocene. As literary scholar Angela L. Robinson (Wito clan of Chuuk) argues in her reading of Jetñil-Kijiner’s 2014 performance of Dear Matefele Peinam, “intercorporeality with nonhuman entities…and the Indigenous ontologies and epistemes it represents, is precisely the kind of sociality needed to change the current trend of climate change.”19Angela L. Robinson, “Of Monsters and Mothers.: Affective Climates and Human-Nonhuman Sociality in Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner’s Dear Matefele Peinam,” The Contemporary Pacific (forthcoming). But what do we make of the muliwai, the shoal, or the wake, when its movements become increasingly erratic, violent, or unpredictable? What happens when the shore is where we begin to measure planetary inhabitability as well as Black and Indigenous survivance? How do we think about the global movement of water and the conditions under which it melts or surges?

Challenging the anthropogenic Anthropocene

The disappearing glacier and the sinking island have become visual bellwethers for the so-called Age of the Anthropocene, the geologic time in which capitalism and colonialism will catch up with its architects.20Heather Davis and Zoe Todd, “On the Importance of Date, or Decolonizing the Anthropocene,” ACME 16, no. 4 (2017): 761–780. As Elizabeth DeLoughrey notes, “630 million people live within 30 feet of the ocean. The current projections for sea level rise are a significant threat to the 10 percent of the world’s population that lives at 10 meters or below, as well as 13 percent of the world’s urban population.” “The Sea is Rising: Visualizing Climate Change in the Pacific Islands,” Pacific Dynamics 2, no. 2 (2018): 238, 241. Extreme weather events, connected to glacial melt and sea-level rise, have produced climate-vulnerable populations as future climate refugees (a subjectivity that many islander communities contest) to be legislated under inequitable national and international agreements.21Carol Farbotko and Heather Lazrus, “The First Climate Refugees? Contesting Global Narratives of Climate Change in Tuvalu,” Global Environmental Change 22, no. 2 (2012): 383. However, commitments to privileging the human condition—what we might call the anthropocentrism of the Anthropocene—draws dangerously upon Enlightenment ideologies that not only imagine humans as separate from environment, but also imagines normative “Man” as distinct from systemically dehumanized Indigenous and Black peoples.22→Angela L. Robinson, “Of Monsters and Mothers,” The Contemporary Pacific (forthcoming).

→Sylvia Wynter, “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom,” CR: The New Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (2003). Because water has the potential to trouble the boundaries of humanness, it may furthermore push us to think through the categorical differences between the diasporic subject and the refugee.

Inspired by Edward Kamau Brathwaite’s use of tidalectics as a conceptual framework for understanding oceanic subjectivities, I want to think about the lessons that water teaches us when it itself is rendered fugitive. If water is by nature diasporic, how do we understand its behavior under the pressures of forced migration? In this sense, to think about the subjectivities that emerge out of the Anthropocene requires us to grapple with the dispossessions of the Holocene: imperialism, settler colonialism, and racial capitalism.23Kathryn Yusoff, “Geologic Realism: On the Beach of Geologic Time,” Social Text 138 37, no. 1 (2019): 2. Following what Sylvia Wynter terms the “coloniality of being,” I highlight both the Western privileging of the human over nonhuman, but also the fact that the Western world has not treated, understood, or legislated many of the world’s people as human.24→Kim TallBear, “Dossier: Theorizing Queer Inhumanisms: An Indigenous Reflection on Working Beyond the Human/Not Human,” GLQ 21, no. 2–3 (2015): 230–235.

→Katherine McKittrick, “Plantation Futures,” Small Axe 17, no. 3 (2013): 1–15. Oceanic movements invite us, then, to think about all of the bodies turned fugitive through colonial capitalism. I wonder: What happens when we turn our attention to the nonhuman in order to track anthropogenic mobilities; not to flatten the categories of human, but, rather, to consider the colonial mechanisms that produced hierarchies of bodies to begin with? Might we understand the refugee as a condition of postcoloniality to which nonhumans are also subjected? How might this, in turn, shape our imagined futures? When we linger with waters at the shore, we open ourselves up to evidence that lands and waters are not distinct from each other, that they both flow and flee, and that keeping good relations is fundamental to a socially just approach to climate change.

Anthropologist Dawn Chatty writes that the project of refugee studies is to “[document and analyze] what happens to people, their culture, and society when they are wrenched from their territorial moorings.”25Dawn Chatty, “Anthropology and Forced Migration,” in The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies, eds. Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh et al. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 74. This formulation, in which the terrestrial operates as conceptual anchor of fugitivity, might be contrasted to the tidal metaphors of diaspora that emerge again and again within Black and brown philosophies of being. If water’s movements are becoming more erratic and wilder as the force of the Anthropocene bears down upon us, then we might consider how the diasporic subject and the fugitive are distinguished—or perhaps bound together—in an ever expanding, ever perilous wake. It is worth returning to the muliwai and its lessons in muddiness, movement, and care to think about the possibilities that emerge from the conditions of change that allow new life to take hold in the shallows.

Banner image: Waukia Estuary, Hilo, Hawai’i. Vintage Postcard, n.d. Image provided by author.

References:

→Christina Sharpe, In the Wake (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).

→Kamau Brathwaite, The Arrivants (Oxford University Press, 1973).

→Manulani Aluli Meyer, Hoʻoulu (Honolulu, Hawaiʻi: ʻAi Pōhaku Press, 2003).

→Vicente M. Diaz, “Voyaging for Anti-Colonial Recovery: Austronesian Seafaring, Achipelagic Rethinking, and the Re-mapping of Indigeneity,” Pacific Asia Inquiry 2, no. 1 (2011).

→Philip Steinberg and Kimberley Peters, “Wet Ontologies, Fluid Spaces: Giving Depth to Volume Through Oceanic Thinking,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 33, no. 2 (2015): 247–264.

→Craig Santos Perez, “Guam and Archipelagic American Studies,” in Archipelagic American Studies, eds. Brian Russell Roberts and Michelle Ann Stevens (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017).

→Stacy Alaimo “Trans-Corporeal Feminisms and the Ethical Space of Nature,” in Material Feminisms, eds. Stacy Alaimo and Susan J. Hekman (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008).

→Sylvia Wynter, “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom,” CR: The New Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (2003).

→Katherine McKittrick, “Plantation Futures,” Small Axe 17, no. 3 (2013): 1–15.