Conspiracy theories have mediated the current Covid-19 pandemic, threatening to turn it into a never-ending crisis. According to salient and popular theories, Covid-19 is: (1) a hoax; (2) a Chinese bioweapon; (3) a US bioweapon; (4) a “plandemic,” by which Bill Gates will dominate the world through microchips planted via vaccines and activated via 5G radio towers; (5) a “plandemic,” by which pharmaceutical companies will make billions through vaccines. The effects of these conspiracies bleed well beyond their proponents. If enough people hesitate to become or refuse to be immunized for Covid-19, we will not attain herd immunity. Countering disinformation distracts from action on containing the pandemic and the inequalities that drive its spread. Decades lost to debating the existence of global climate change have made this clear. Conspiracy theories threaten to make the Covid-19 virus—in addition to many strands of disinformation—forever undead.

Crucially, debunking conspiracy theories does not appear to be the most effective way to dispel or combat them. “Red-pilling,” used by many believers to explain their recruitment into certain conspiracy beliefs, exemplifies how clear, visible evidence is not only insufficient, but can also become inherently suspect. This phrase refers to the scene in The Matrix, in which the protagonist Neo chooses to take the red pill in order to discover the “truth,” namely that the visible world is really a computer simulation.

“Corrections and misinformation can reach very different audiences, and corrections can inadvertently keep debunked stories alive…”This resistance to factchecking—seemingly in favor of fictional narratives that speak greater, invisible truths—extends beyond conspiracy theories. Redpilling has become a general synonym for waking up to to the “truth.” Further, widespread forms of mis- or disinformation have revealed that fact-checking, though important, is not enough. Fact-checking sites lag behind the deluge of rumors produced by disinformation sources and spread via private interactions. Corrections and misinformation can reach very different audiences, and corrections can inadvertently keep debunked stories alive;1→Chengcheng Shao et al., “Anatomy of an Online Misinformation Network,” PLoS ONE 13, no. 4 (2018).

→Craig Silverman, Lies, Damn Lies, and Viral Content (Tow Center for Digital Journalism, Columbia University, New York, 2015). even users who care about accuracy spread stories they find compelling, regardless of their facticity.2Gordon Pennycook et al., “Shifting Attention to Accuracy Can Reduce Misinformation Online,” Nature, March 17, 2021.

Due to this seeming resistance to corrections and the spread of “fake news,” this era has been called one of “posttruth,” that is, one in which emotions matter more than facts. Intriguingly though, the 2016 US presidential election was described as both normalizing “fake news” and as the “authenticity election.” Indeed, one candidate—the eventual winner and early “birther”—scored high on both. Arguably, the more he railed against the mainstream media and endorsed what his administration would later call “alternative facts,” the more authentic he appeared. This seeming contradiction reveals a profound difference in the subject or object of truth—and the historical and semantic differences between truth and facts.3→Daniel Rosenberg, “Data before the Fact,” in “Raw Data” Is an Oxymoron, ed. Lisa Gitelman (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2013), 15–40.

→Steven Shapin, A Social History of Truth: Civility and Science in Seventeenth-Century England (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1994).

→Mary Poovey, A History of the Modern Fact: Problems of Knowledge in the Sciences of Wealth and Society (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998). Politicians such as Trump and Sanders were considered “authentic” because they allegedly said what they believed, rather than what they thought others wanted to hear. They were transparent, and thus were perceived as authentic.

Most simply, authenticity, as Lionel Trilling has argued, is the (dramatic) command: “to thine own self be true.”4 Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972More Info → It demands that a person’s outside and inside coincide—that people, like media, appear “untampered.” In the contemporary period, it implies a vocal disregard for convention: a “subversiveness” or brashness that indicates that a person has no borders or filters.5Wendy H. K. Chun, Discriminating Data (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2021). People have been coaxed into revealing “inner” secrets or deviations, and as Sarah Banet-Weiser has shown in her definitive analysis of authenticity, called to engage in constant and seemingly spontaneous interchanges with others.6

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972More Info → It demands that a person’s outside and inside coincide—that people, like media, appear “untampered.” In the contemporary period, it implies a vocal disregard for convention: a “subversiveness” or brashness that indicates that a person has no borders or filters.5Wendy H. K. Chun, Discriminating Data (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2021). People have been coaxed into revealing “inner” secrets or deviations, and as Sarah Banet-Weiser has shown in her definitive analysis of authenticity, called to engage in constant and seemingly spontaneous interchanges with others.6 New York: NYU Press, 2012More Info → The greatest “sin” within the politics of authenticity is to be “fake,” a hypocrite—to reveal an “inside,” which contradicts one’s outer self.

New York: NYU Press, 2012More Info → The greatest “sin” within the politics of authenticity is to be “fake,” a hypocrite—to reveal an “inside,” which contradicts one’s outer self.

Planning the “self”

This authenticity, however, is highly algorithmic, which is to say that transgressions of “authentic characters” are most often carefully planned and groomed: How-to primers teach business leaders and social media microstars how to be authentic in order to brand success; “reality” TV is a highly-scripted and formatted version of television programming.7→Will Burns, “Donald Trump And Bernie Sanders Show Us The Value Of Authenticity In Marketing Political Candidates,” Forbes, August 12, 2015.

→Fiona Kennedy and Darl Kolb, “The Alchemy of Leadership,” University of Auckland Business Review 19, no. 2 (2016): 7. Pointing this out—as many did during the 2016 election campaign—though, is hardly effective or profound.8Chun, Discriminating Data. As Banet-Weiser has shown, authenticity has itself become a brand.9Banet-Weiser, Authentic™.

Further, the relationship between truth, facts, authenticity, and media is and has been complicated. The move to call society “posttruth” because of “fake news” erases important differences between truth, factuality, and authenticity, emphasized by historians and historians of science.10See Poovey, A History of the Modern Fact, and Shapin, A Social History of Truth. It also ignores extensive research into the relationship between media and evidence; authenticity and politics. Media studies and political theory have highlighted the centrality of authenticity and rhetoric to trust and politics.11→Danielle Allen, Talking to Strangers: Anxieties of Citizenship since Brown v. Board of Education (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2006).

→Marshall Berman, The Politics of Authenticity: Radical Individualism and the Emergence of Modern Society (New York: Verso, 2009).

→Rebecca Lewis, Alternative Influence: Broadcasting the Reactionary Right on Youtube (New York: Data and Society, 2018). Literary and African American studies have emphasized the importance of fiction, or critical fabulation, to truth-telling.12Saidiya Hartman, “The Anarchy of Colored Girls Assembled in a Riotous Manner,” South Atlantic Quarterly 117, no. 3 (2018): 465–487. Indigenous studies and anthropology have revealed the costs and benefits of the politics of authenticity.13→Paige Raibmon, Authentic Indians Episodes of Encounter from the Late-Nineteenth-Century Northwest Coast (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005).

→Elizabeth A. Povinelli, The Cunning of Recognition: Indigenous Alterities and the Making of Australian Multiculturalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002).

An interdisciplinary investigation of authenticity thus allows us to examine the twinning of performance and authenticity in a way that does not treat it as irrational or accidental—a roadblock to analysis—but rather as formative and general. It focuses on the question: Why and how—under what circumstances (social, cultural, technical, and political)—do people find information to be true or authentic? It moves us from asking “why do people mistrust mainstream media?” to investigating why and how they come to trust alternative media, to asking: Why and how does questioning CNN lead to trusting Brietbart?

Most succinctly, the following research questions become essential:

- What makes information feel authentic, regardless of its facticity?

- How do users negotiate the demand to be authentic?

- Who benefits from authenticity? What are the affective and financial economies of authenticity?

- What relations and infrastructures does authenticity require/foster?

- What actions register as authentic and how? What counts as evidence? What is the relationship between authenticity and facticity?

- What does the turn to authenticity enable and disqualify?

Authenticity supplements behavioralist models of users, which presume that users are marionettes or lab rats, controlled by social media.14The Social Dilemma, directed by Jeff Orlowski, written by Jeff Orlowsky, Vickie Curtis, and Davis Coombe, 2020, Netflix. As many researchers have shown, social media users craft personas online with public/social engagement in mind.15→danah boyd, It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014).

→Stephanie Duguay, “Dressing up Tinderella: Interrogating Authenticity Claims on the Mobile Dating App Tinder,” Information, Communication & Society 20, no. 3 (2017): 1–17.

→Gunn Enli, Mediated Authenticity: How the Media Constructs Reality (New York: Peter Lang, 2015).

→Gunn Enli, “Twitter as Arena for the Authentic Outsider: Exploring the Social Media Campaigns of Trump and Clinton in the 2016 US Presidential Election,” European Journal of Communication 32, no. 1 (2017): 50–61.

→Dawn R. Gilpin, Edward T. Palazzolo, and Nicholas Brody, “Socially Mediated Authenticity,” Journal of Communication Management 14, no. 3 (2010): 258–278. Performance grounds identity in ways that are neither cynical nor insincere.16→Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1959).

→Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1999). It is no accident that The Matrix is a film. It is also no accident the popular documentary The Social Dilemma deploys animation and fictional representations of a multiracial suburban family; and features re-takes and backstage perspectives of its tech-bro experts.

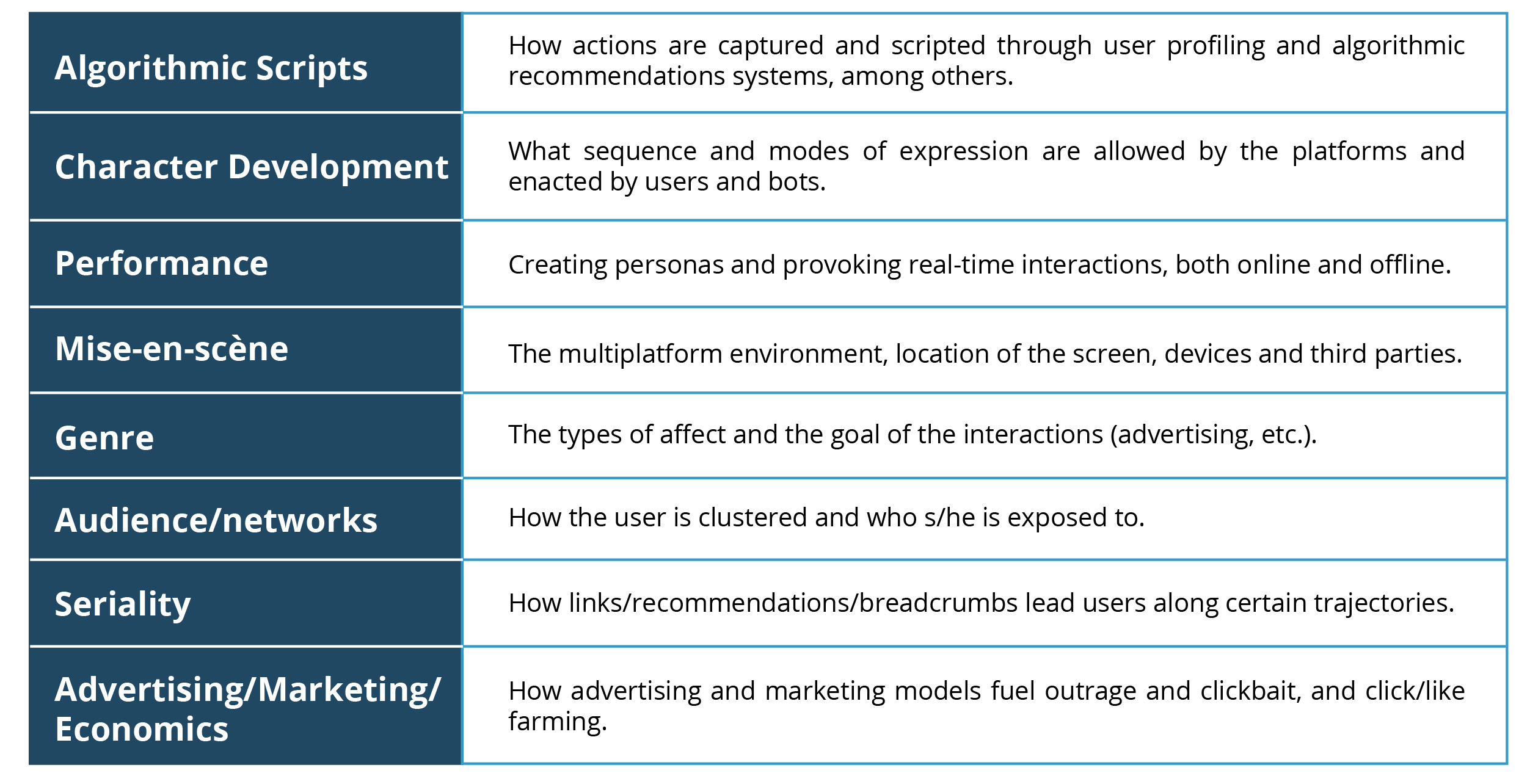

To study authenticity, a performance-based schema, which outlines the following aspects at the very least, is key:

To understand the impact of authenticity, we need to also understand how these categories interact. Crucially, the imperative “be true to yourself,” or more simply “be true,” has made our data valuable, that is recognizable, across the many media platforms we use—all in the name of safety and comfort. To ensure this safety, digital companies have increased demands for user authentication, which was pitched as a way to make online spaces safe. Corporations such as Google and Facebook, whose data mining operations require user authentication, supported and continue to support tethering on and offline identities. Randi Zuckerburg, marketing director of Facebook, argued in 2011 that, for the sake of safety, “[a]nonymity on the internet has to go away”;17Bianca Bosker, “Facebook’s Randi Zuckerberg: Anonymity Online ‘Has To Go Away’,” HuffPost, September 26, 2011. Eric Schmidt, CEO of Google, made a similar argument in 2010 stating, “in a world of asynchronous threats, it is too dangerous for there not to be some way to identify you.”18Bianca Bosker, “Eric Schmidt on Privacy (VIDEO): Google CEO Says Anonymity Online Is ‘Dangerous’,” HuffPost, August 10, 2010, updated December 6, 2017. These arguments were not new or specific to Web 2.0. Ever since the internet emerged as a mass medium in the mid-1990s, corporations have argued that securing identity is crucial to securing trust and safety.

Trusting the “self”

“If authenticity is the act of being ‘true to ourselves,’ then we need some way to authenticate that ‘self’ and protect our data from outside threats.”If authenticity is the act of being “true to ourselves,” then we need some way to authenticate that “self” and protect our data from outside threats. User authentication, however, has not made the internet a safe space—although it has normalized e-commerce. Revenge porn, for example, does not rely solely on anonymity, but also on an initial trusted transmission. Cyberbullying has not gone away. Attacks orchestrated via Instagram or text messages by people one knows are arguably more damaging than ones by anonymous strangers. More precisely, as the Amanda Todd and other cases reveal, it is the combination of the two that makes them so powerful.19 Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2016More Info → As Helen Nissenbaum, writing in 2001, noted, although security is central to activities such as e-commerce and banking, it can “no more achieve trust and trustworthiness, online—in their full-blown senses—than prison bars, surveillance cameras, airport X-ray conveyor belts, body frisks, and padlocks, could achieve offline. This is so because the very ends envisioned by the proponents of security and e-commerce are contrary to core meanings and mechanisms of trust.”20Helen Nissenbaum, “Securing Trust Online: Wisdom or Oxymoron,” Boston University Law Review 81, no. 3 (2001): 655. The reduction of trust to security assumes that danger stems from outsiders, rather than “sanctioned, established, powerful individuals and organizations.” In contrast, Nissenbaum stresses that trust entails vulnerability. In a realm in which everything is secure, trust is actually not needed: “When people trust, they expose themselves to risk. Although trust may be based on something—past experience, the nature of one’s relationships, and so on—it involves no guarantees.”21Nissenbaum, “Securing Trust Online,” 662, 656.

Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2016More Info → As Helen Nissenbaum, writing in 2001, noted, although security is central to activities such as e-commerce and banking, it can “no more achieve trust and trustworthiness, online—in their full-blown senses—than prison bars, surveillance cameras, airport X-ray conveyor belts, body frisks, and padlocks, could achieve offline. This is so because the very ends envisioned by the proponents of security and e-commerce are contrary to core meanings and mechanisms of trust.”20Helen Nissenbaum, “Securing Trust Online: Wisdom or Oxymoron,” Boston University Law Review 81, no. 3 (2001): 655. The reduction of trust to security assumes that danger stems from outsiders, rather than “sanctioned, established, powerful individuals and organizations.” In contrast, Nissenbaum stresses that trust entails vulnerability. In a realm in which everything is secure, trust is actually not needed: “When people trust, they expose themselves to risk. Although trust may be based on something—past experience, the nature of one’s relationships, and so on—it involves no guarantees.”21Nissenbaum, “Securing Trust Online,” 662, 656.

Calls to be authentic also ground the fracturing of what was once mainstream culture into highly agitated clusters of sameness, crucial for clickbait-based forms of advertising. Many exposés have revealed the microcategories, based on “distinctive” likes, that drive online advertising. Users are targeted and combined—“batched and bucketed” into “behavioral tribes” using the most distinctive—that is discriminatory—features.22 New York: Crown, 2016More Info → By “liking” certain pages or posts or buying certain products, which document how they deviate from the norm with others, users become more effectively targeted. Kosinski’s early analysis of Facebook likes, for example, argued that liking Britney Spears was a strong indicator of male homosexuality.23Michal Kosinski, David Stillwell, and Thore Graepel, “Private Traits and Attributes Are Predictable from Digital Records of Human Behavior,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110, no. 15 (2013): 5802. As I argue in more detail in my forthcoming book, Discriminating Data, if hegemony once meant the creation of a majority by various minorities accepting a dominant world view (such as Greece accepting Athenian values), hegemony is now formed by bringing together angry or affectively-charged minorities, clustered around a shared stigma/subcultural style.

New York: Crown, 2016More Info → By “liking” certain pages or posts or buying certain products, which document how they deviate from the norm with others, users become more effectively targeted. Kosinski’s early analysis of Facebook likes, for example, argued that liking Britney Spears was a strong indicator of male homosexuality.23Michal Kosinski, David Stillwell, and Thore Graepel, “Private Traits and Attributes Are Predictable from Digital Records of Human Behavior,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110, no. 15 (2013): 5802. As I argue in more detail in my forthcoming book, Discriminating Data, if hegemony once meant the creation of a majority by various minorities accepting a dominant world view (such as Greece accepting Athenian values), hegemony is now formed by bringing together angry or affectively-charged minorities, clustered around a shared stigma/subcultural style.

All these examples bring us back to the relationship between trust, truth, and authenticity. Modern notions of truth, as Stephen Shapin has shown, are linked historically to the rise of “trusted circles”—groups and protocols of gentlemen scientists—within eighteenth-century science.24Shapin, A Social History of Truth. Rhetoric, as Danielle Allen has shown, does not detract from but rather grounds trust.25Allen, Talking to Strangers, 140-60. Again, this is not to say that trust is an illusion or that authenticity fraudulent, but rather that attending to their complexities and histories moves us away from endless debates over whether something is real—to prolonging crises in the name of knowledge—toward engaging outcomes, motivations, and effects.

This work was made possible in part by funding by the Canada 150 Research Chairs program and the Canadian Social Science and Humanities Research Council. It is part of the Beyond Verification Project, which includes Ganaele Langlois, Javier Ruiz Soler, Ioana Jucan, Alex Juhasz, Roopa Vasudevan, Anthony Burton, Melody Devries, Anthony Burton, Jasmine Proctor, Denise Toor, Esther Weltevrede, Liliana Bournegru, Heidi Tworek, and Amy Harris.

References:

→Craig Silverman, Lies, Damn Lies, and Viral Content (Tow Center for Digital Journalism, Columbia University, New York, 2015).

→Steven Shapin, A Social History of Truth: Civility and Science in Seventeenth-Century England (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1994).

→Mary Poovey, A History of the Modern Fact: Problems of Knowledge in the Sciences of Wealth and Society (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998).

→Fiona Kennedy and Darl Kolb, “The Alchemy of Leadership,” University of Auckland Business Review 19, no. 2 (2016): 7.

→Marshall Berman, The Politics of Authenticity: Radical Individualism and the Emergence of Modern Society (New York: Verso, 2009).

→Rebecca Lewis, Alternative Influence: Broadcasting the Reactionary Right on Youtube (New York: Data and Society, 2018).

→Elizabeth A. Povinelli, The Cunning of Recognition: Indigenous Alterities and the Making of Australian Multiculturalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002).

→Stephanie Duguay, “Dressing up Tinderella: Interrogating Authenticity Claims on the Mobile Dating App Tinder,” Information, Communication & Society 20, no. 3 (2017): 1–17.

→Gunn Enli, Mediated Authenticity: How the Media Constructs Reality (New York: Peter Lang, 2015).

→Gunn Enli, “Twitter as Arena for the Authentic Outsider: Exploring the Social Media Campaigns of Trump and Clinton in the 2016 US Presidential Election,” European Journal of Communication 32, no. 1 (2017): 50–61.

→Dawn R. Gilpin, Edward T. Palazzolo, and Nicholas Brody, “Socially Mediated Authenticity,” Journal of Communication Management 14, no. 3 (2010): 258–278.

→Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1999).