In the year since the novel coronavirus appeared in the United States, more than 30 million Americans have contracted the virus and over 500,000 have died from Covid-19. However, caseloads and deaths are not evenly spread across the population and certain groups have suffered substantially higher rates of infection, illness, and death. Across the country, inmates in jails and prisons have had four times as many infections and more than twice the death rate compared to the rest of the population. The widespread infections and loss of life in jails and prisons were easy to predict given chronic overcrowding; as a doctor at Rikers Island in New York noted, “the right preventive measures don’t exist to stop the spread of this virus” in correctional institutions.

As reports of Covid infections in lock-up spread, activists have pushed to reduce jail and prison populations via petitions and letter writing campaigns on behalf of vulnerable prisoners and fundraising for bail funds. Some political leaders responded to this pressure by releasing prisoners in response to Covid. New Jersey passed a law in October 2020 that allowed for the release of inmates with fewer than one year remaining on their sentences, and some sheriffs released county inmates to reduce their jail populations, although this was not sustained as the pandemic wore on.

“In many ways people who are incarcerated rely on those who are not incarcerated, and thus have more audible political voices, to advocate for them.”Clearly, some in the public were moved to advocate on behalf of those in jails and prisons in the face of a public health crisis. Despite the massive growth of incarceration and the estimated 4.5 million Americans currently under community supervision, incarcerated people remain politically invisible. People in prison and jail are literally removed from their communities, and frequently have their political rights curtailed both via legal disenfranchisement and the erosion of democratic rights within correctional facilities.1→Amy Lerman and Vesla Weaver, Arresting Citizenship: The Democratic Consequences of American Crime Control (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2014).

→Loïc Wacquant, “Race as Civic Felony,” International Social Science Journal 57 no. 183 (2005): 127–142. Therefore, in many ways people who are incarcerated rely on those who are not incarcerated, and thus have more audible political voices, to advocate for them. Yet, political science still knows relatively little about how Americans can be moved to participate in service of someone else’s interests. In this study, I ask and test whether perspective-taking exercises, either about oneself or one’s loved ones, might induce Americans to mobilize for the release of incarcerated people.

Empathy and surrogate mobilization

Political science scholarship shows that empathy can reduce animus against other social groups and encourage the public to advocate on behalf of others.2→Claire L. Adida, Adeline Lo, and Melina R. Platas, “Perspective Taking Can Promote Short-term Inclusionary Behavior toward Syrian Refugees,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, no. 38 (2018): 9521–9526.

→David Broockman and Joshua Kalla, “Durably Reducing Transphobia: A Field Experiment on Door-to-Door Canvassing,” Science 352, no. 6282 (2016): 220–224. Adida, Lo, and Platas use a perspective-taking exercise that encourages respondents to imagine themselves in the place of a refugee.3Adida, Lo, and Platas, “Perspective Taking.” This type of perspective-taking can encourage people to view others as more similar to themselves—or “a merging of the self and the other”4Adam D. Galinksy and Gordon B. Moskowitz, “Perspective-Taking: Decreasing Stereotype Expression, Stereotype Accessibility, and In-Group Favoritism,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 78, no. 4 (2000): 709.—which promotes empathetic responses and helping behaviors. They show that this exercise induces empathy toward refugees, making respondents both more welcoming of refugees and more willing to act on their support for refugees by writing a letter to the president.

In the context of the carceral state, or those institutions concerned with supervision and control, a growing body of work shows that vicarious or proximal contact can encourage political action. While personal contact with carceral institutions—such as being searched by police, arrested, or incarcerated—often results in the absorption of negative political lessons and a retreat from political life,5Lerman and Weaver, Arresting Citizenship. when one’s friends and family have carceral contact it can actually promote political participation due to a sense of injustice.6Hannah L. Walker, “Extending the Effects of the Carceral State: Proximal Contact, Political Participation, and Race,” Political Research Quarterly 67, no. 4 (2014): 809–22. This is often referred to as surrogate participation, “when those with political power represent the needs of others who lack power, often prompted by a social or emotional tie.”7Allison Anoll and Mackenzie Israel-Trummel, “Do Felony Disenfranchisement Laws (De)Mobilize? A Case of Surrogate Participation,” Journal of Politics 81, no. 4 (2019): 1523. Indeed, surrogate participation has been identified in areas beyond the carceral state as people feel a responsibility to amplify the political voice of those who may have less access to political power.8Walter Clark Wilson and William Curtis Ellis, “Surrogates beyond Borders: Black Members of the United States Congress and the Representation of African Interests on the Congressional Foreign-Policy Agenda,” Polity 46, no. 2 (2014): 255–73.

Study design

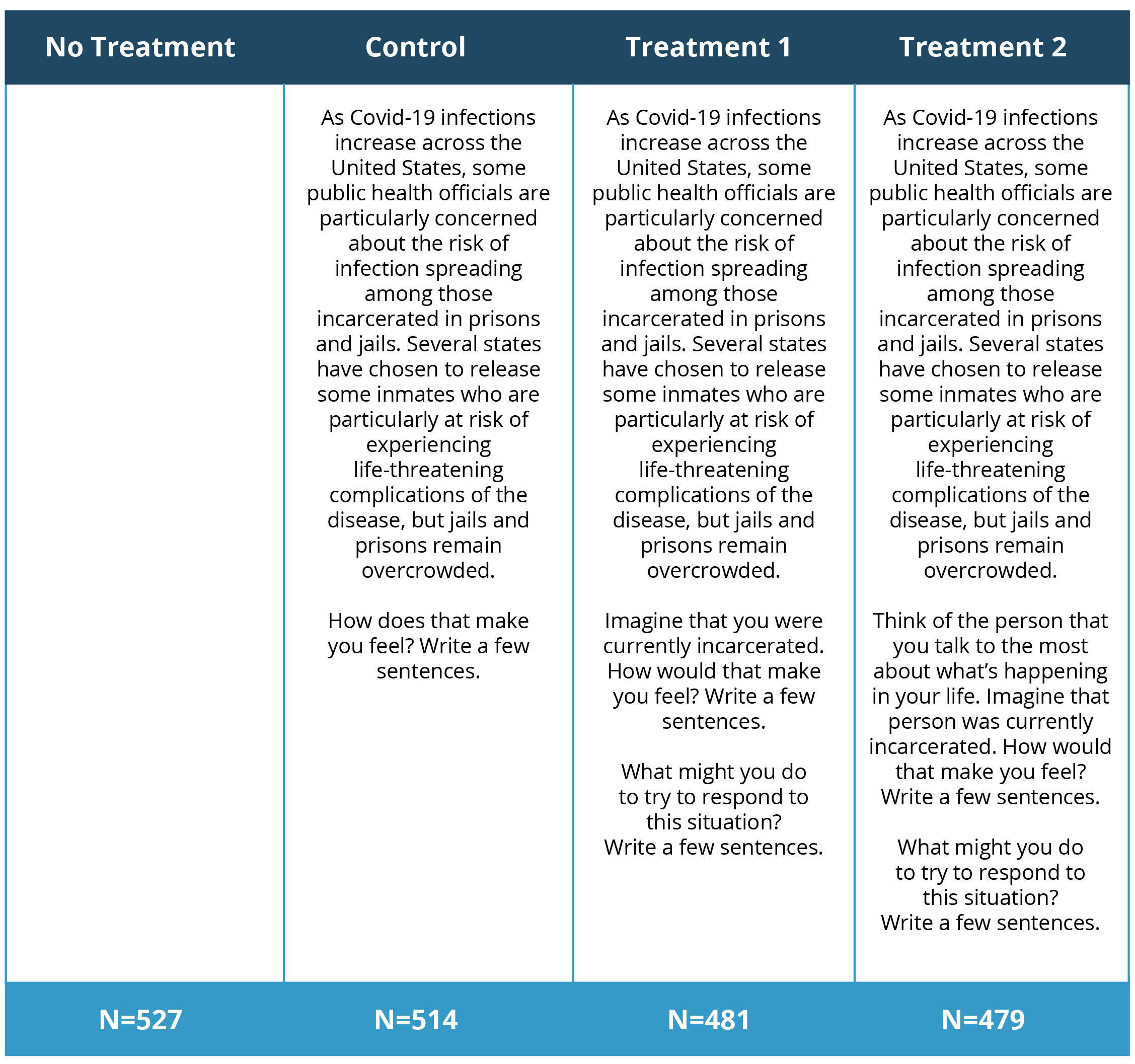

To test the effects of perspective-taking, I fielded an online survey experiment to a diverse national sample of 2,001 Americans in December 2020. The experiment featured four conditions: no treatment, a control message, and two perspective-taking treatments (see Table 1). The perspective-taking treatment conditions attempt to induce empathy—by imagining either themselves or their loved one in the position of inmates. The four treatment conditions are provided in Table 1.

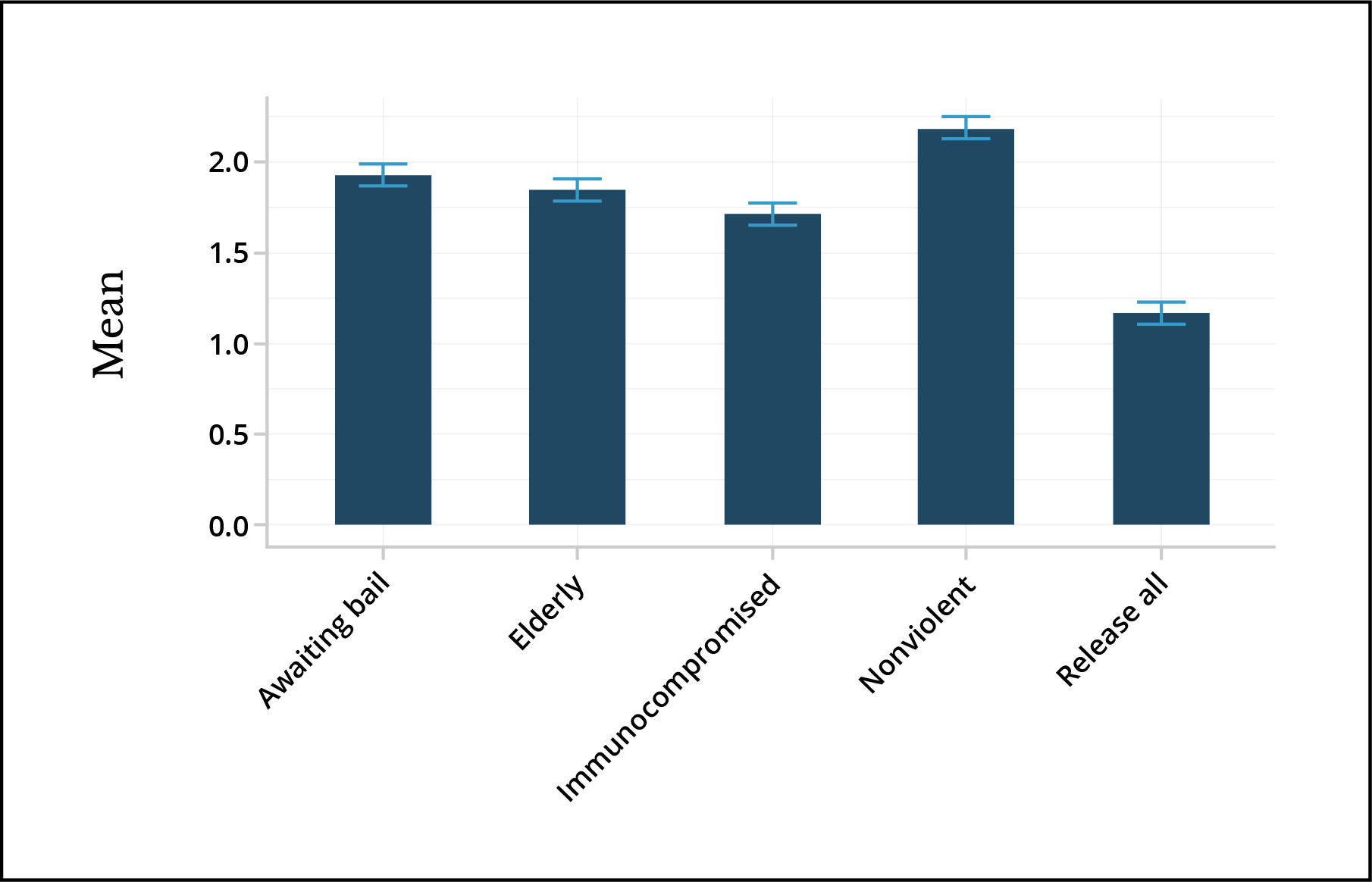

I analyze the effects of the treatments on support for inmate release. First, I capture support for releasing inmates due to the pandemic with five measures indexed together to create a scale that ranges from 0 to 20.9Cronbach’s alpha for the scale is 0.89. These items capture support for releasing inmates generally, elderly inmates, immunocompromised inmates, nonviolent inmates, and those in jail because they are unable to afford bail.

Effects of perspective-taking exercises

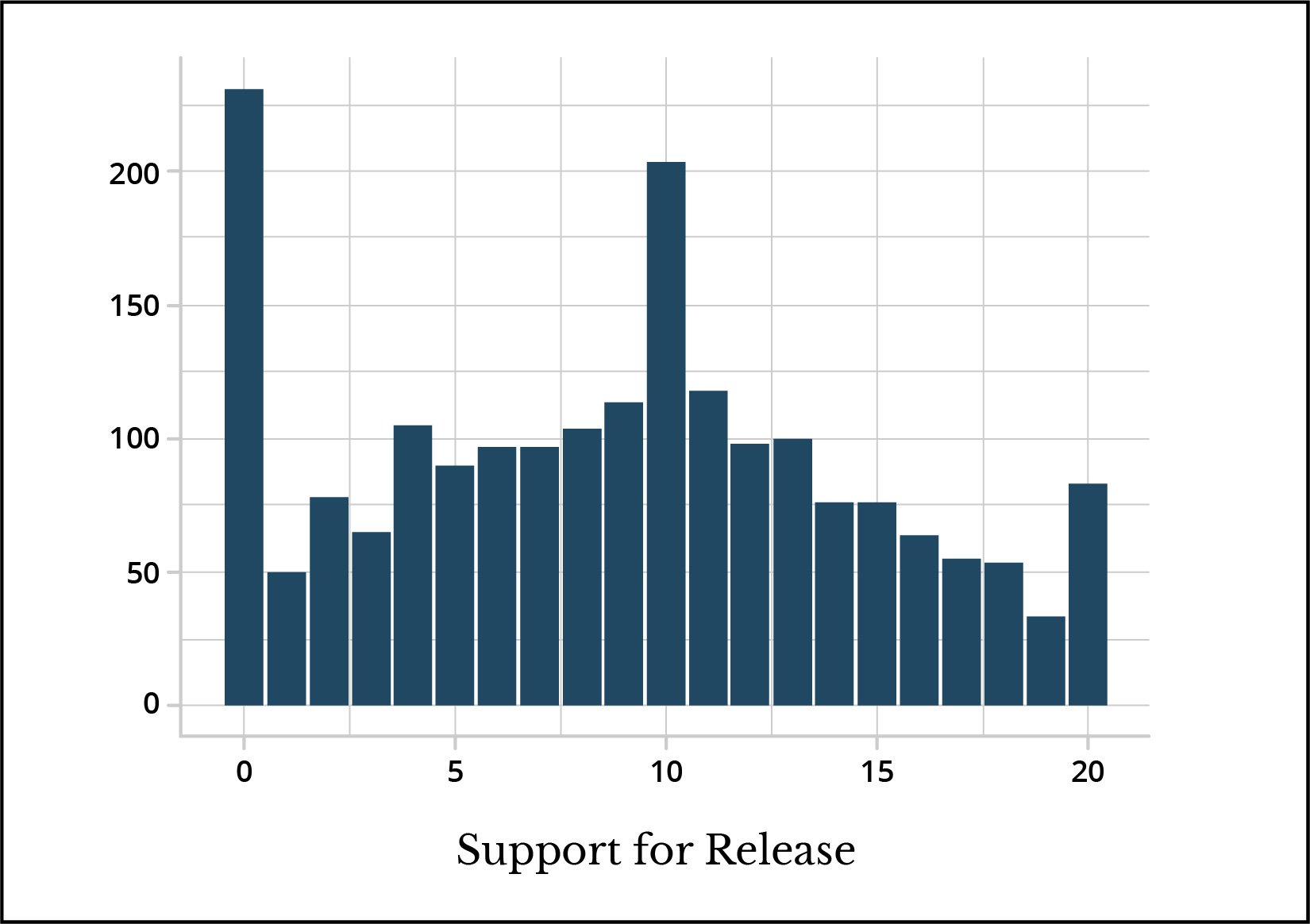

First, I show average levels of support for releasing inmates in response to the public health conditions inside jails and prisons. Generally, respondents do not favor releasing inmates. As shown in Figure 1, the highest level of support is for releasing nonviolent offenders, but the mean level of support on this measure is only 2.19 on a 0 to 4 scale. This means the average score is just slightly above “neither agree nor disagree.” For all other items, the average score falls below the midpoint, indicating more opposition than support for releasing inmates. When the individual items are indexed together, there is a cluster of respondents at the middle of the index, but there are also clusters of respondents who place themselves at either endpoint. As Figure 2 shows, the modal response on the index is 0, which indicates the strongest opposition to prisoner release. The descriptive quantitative analysis suggests that this is a divisive political issue for Americans.

I offered respondents the option to provide their comments on the topic of prisoner release, and this qualitative data underscores the quite polarized views of the topic. Comments in support of release tended to be somewhat qualified, as respondents often noted that they did not support releasing all inmates, but would, for example, support releasing nonviolent offenders. One respondent wrote, “It depends on why they’re in jail, I don’t think I would want violent people roaming the streets,” while another said, “It’s a wise decision to think about releasing the inmates. However, please kindly judge the inmates’ character and behavior before releasing.” While some respondents voiced support for releasing at least some inmates, others indicated their anger with the proposal. Many respondents wrote variations of “they did the crime; they should do the time” while others used dehumanizing language to describe inmates (referring to them as “rodents”) and showed indifference to deaths within corrections facilities (“if you die, you die” and “let them die”).

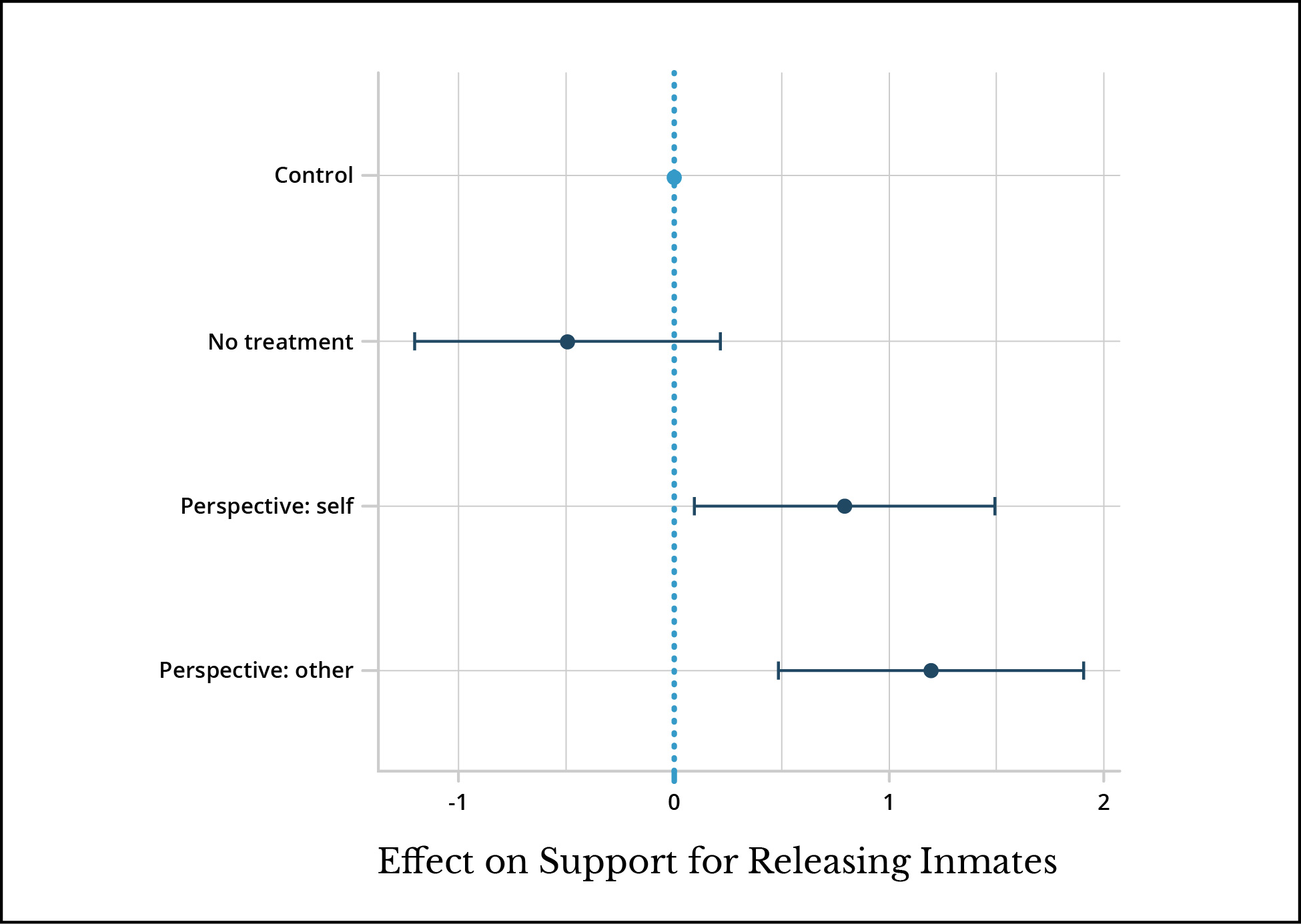

There appears to be relatively limited public appetite for releasing inmates amidst the pandemic. However, can perspective-taking exercises increase support for compassionate release? The answer is yes. Figure 3 shows that relative to both the no treatment and control conditions, the perspective-taking interventions increased support for releasing inmates. Simply telling respondents about conditions in jails and prisons in the control does not change support for release relative to the no treatment condition. But when respondents are asked to think about what they would do if they or a loved one were in jail or prison, it significantly increases support for release. Respondents participating in the perspective-taking treatments, when asked how imagining themselves or their loved ones being incarcerated makes them feel, responded with the expected empathetic responses, indicating that they would feel “bad,” “scared,” “sad,” and “lonely.” By comparison, in the control condition although some respondents indicated empathy for those behind bars, others focused on the risk of prisons seeding outbreaks that could reach them (“A little worried of catching it but not too scared as long as I do the precautions”) or noted that they didn’t care what happened to prisoners during the pandemic (“Criminals have no right to this world, so it wouldn’t matter if they died or not”). Many respondents also used this space to voice opposition to the release of inmates rather than focusing on the feelings elicited by the treatment condition. This suggests the perspective-taking exercise was successful in prompting empathetic emotions from respondents.

Importantly, I do not find differences between perspective-taking on behalf of oneself and one’s loved ones. This suggests empathy can be fostered not just by imagining oneself in a particular social position, but also one’s loved ones. This is politically meaningful as many more people are vicariously connected to the carceral state than immediately impacted; nearly half of Americans have had a family member incarcerated.10Peter K. Enns et al., “What Percentage of Americans Have Ever Had a Family Member Incarcerated?: Evidence from the Family History of Incarceration Survey (FamHIS),” Socius 5 (2019): 1–45. These findings provide causal evidence that interventions designed to promote empathy can make Americans more supportive of releasing inmates during a public health crisis. Moreover, these results suggest that perspective-taking might be a powerful tool when it comes to building support for decarceration and abolition efforts. Public opinion played a key role in the growth of the carceral state,11 New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016More Info → and will be essential to political efforts to dismantle punitive institutions. Organizations that seek to mobilize public opinion against carceral punishment may see success by leveraging these types of rhetorical strategies.

New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016More Info → and will be essential to political efforts to dismantle punitive institutions. Organizations that seek to mobilize public opinion against carceral punishment may see success by leveraging these types of rhetorical strategies.

Banner photo: Joe Piette/Flickr.

References:

→Loïc Wacquant, “Race as Civic Felony,” International Social Science Journal 57 no. 183 (2005): 127–142.

→David Broockman and Joshua Kalla, “Durably Reducing Transphobia: A Field Experiment on Door-to-Door Canvassing,” Science 352, no. 6282 (2016): 220–224.