In the spring of 2006, more than three million immigrants—most of them originally from Mexico—marched through the streets of Chicago, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Milwaukee, Detroit, Denver, Dallas, and dozens of other U.S. cities to protest peacefully for a comprehensive reform that would legalize the status of millions of undocumented immigrants in the United States.1This essay draws from a new report on a conference held November 4-5, 2005 at the Mexico Institute of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, co-sponsored by the Department of Latin American and Latino Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz, with funding from the Rockefeller, Ford and Inter-American foundations. Titled “Invisible No More: Mexican Migrant Civic Participation in the United States,” and edited by Xóchitl Bada, Jonathan Fox, and Andrew Selee, the report is available at http://www.wilsoncenter.org/migrantparticipation. Though few are voters, and even fewer in swing districts, migrants’ remarkably disciplined, law-abiding collective actions sent a message—“we are workers and neighbors, not criminals”—that resonated on Capitol Hill. The protests caught almost all observers by surprise, including many in immigrant communities. Mexican migrants, who formed a majority of participants in most of the cities, moved from being subjects of policy reform to having a voice in the debate on the reform. Never before had they taken such a visible role in a national U.S. policy discussion.

The decision by so many immigrant workers, housewives, students, farmworkers, both seniors and children, to come together to pursue a right to full membership in U.S. society suggests a major turning point in what has been the slow but steady construction of a shared pan-Latino immigrant collective identity in the United States. “Today we march, tomorrow we vote,” was one of the most popular slogans in these series of protests in a short two-month period.

The beginning of this social movement has marked a new era where many Mexicans, Salvadorans, Guatemalans or Dominicans, each closely identified with their nation of origin, are also increasingly accepting the U.S. labels Latino or Hispanic. Yet in order to understand the social foundations of this broad new upsurge in Latino immigrant participation, it is also useful to address the dynamics that are specific to those who came from Mexico. It is critical to understand how and why they choose to engage with public life in the United States.

This huge wave of civic engagement reveals a process that has been taking place often silently but consistently: the emergence of Mexican migrants as actors in American civic and political life. Far from the image of Mexican migrants as disengaged and insular, they have long been active in public life. They have done so by creating new migrant-led organizations, such as hometown associations, workers’ organizations and community media, as well as by joining existing U.S. organizations, such as community associations, churches, schools, unions, business associations, and civil rights organizations. In the process, they are also transforming these U.S. institutions, as so many other immigrant groups have done throughout American history.

Many Mexican migrants not only contribute to civic and political endeavors in U.S. society, but also remain simultaneously engaged as part of a cross-border Mexican society. Rather than producing a contradiction of divided loyalties, these dual commitments often tend to be mutually reinforcing. Recent research on Mexican migrant organizations indicates that efforts to help their hometowns in Mexico often leads to increasingly strategic engagement with civic life in their new hometowns in the United States.

There are over 600 registered hometown associations formed by Mexican migrants in cities and towns throughout the United States, with an especially notable presence in Chicago and Los Angeles. Many of these associations have formed federations made up of people from the same state in Mexico, as well as emerging confederations that in turn bring together different federations in U.S. metropolitan areas. These organizations play a significant role in helping hometowns in Mexico through encouraging community investment of collective remittances and pushing for more government support through matching funds. The larger federations have developed an increasing capacity to hold Mexican public officials accountable for the use of funds that are sent to Mexico to assist in infrastructure and productive projects in their towns of origin.

In addition, many of these hometown associations, federations, and confederations are becoming important participants in U.S. civic life. Most of these organizations started out focused exclusively on aid to their home communities in Mexico, but over time many developed programs for families and communities in the United States. They have thus become important arenas for migrants to learn the skills that allow them to engage with U.S. society and in many cases they have become active participants in city and state policy discussions that affect migrant communities. Migrants who participate in these associations often claim membership simultaneously in both Mexican and U.S. societies, what we call “civic binationality,” with their initial engagement with hometowns abroad aiding in their transition to active engagement with U.S. society. Some organizations, such as the Binational Front of Indigenous Organizations (FIOB), actually maintain binational membership structures that allow for simultaneous engagement in both Mexican and U.S. societies.

U.S. Latino civil society, including both public interest groups and community-based organizations, offers a major pathway for immigrant incorporation into U.S. society. Traditional Latino organizations and Mexican migrant organizations often overlap in their issues and sometimes even membership, though they often have very different organizational structures, access to resources, as well as different views on whether to pursue a binational or primarily U.S.-focused agenda. While traditional Latino organizations tend to focus on civil rights in the U.S. and questions of equal access to healthcare and education, migrant organizations tend to focus on binational issues and on service access issues that specifically affect immigrants. U.S. Latino leaders are among the U.S. constituencies most strongly committed to promoting immigrant incorporation, though they differ over whether migrants’ binational perspectives are win-win or win-lose from the point of view of eventual integration into U.S. society. Nonetheless, the gap between these agendas is narrowing as Mexican migrant organizations become increasingly involved in U.S.-based agendas and Latino organizations increasingly embrace concerns of the growing number of U.S. Latinos who are migrants. Our November 2005 Woodrow Wilson Center seminar found that both sets of leaders are “in transition” regarding these issues, creating new opportunities for dialogue and synergy. For another example, the July 2006 national conference of the National Council of La Raza involved an unprecedented degree of outreach to immigrants, including widespread interest in citizenship promotion and Spanish-language workshops.

Mexican migrants have also become increasingly influential members and leaders of traditional U.S. civic organizations as well, and these have served as important vehicles for migrants to become active members of U.S. society. Religious communities, both Catholic and Protestant, have played particularly important roles in creating channels for migrants to become engaged with issues in their U.S. congregations. Indeed, a large part of the growth of both the Catholic and evangelical Christian churches has come from Latin American immigrants. Some faith-based migrant membership organizations, such as the Asociación Tepeyac in New York, specifically see their role as building the social and political engagement of migrants to give them a voice in U.S. society while they continue to engage with their country of origin. These communities appropriate symbols and patterns of worship from migrants’ hometowns in Mexico but also address issues that migrants face in the United States.

Worker organizations have become another key arena for migrants’ civic engagement, in defense of their labor rights. Mexican migrant workers express a similar level of interest in unions to others in the United States despite most migrants’ lack of prior experience with representative unions in Mexico. Latin American immigrants have been central to most recent successful efforts to unionize private sector workers. Many migrants work in largely non-unionized industries, especially agriculture, construction and services, and here the emergence of worker support centers and other non-union forms of organization has proved particularly important. For immigrant farmworkers, who are often geographically and socially isolated, outreach to U.S. public opinion has often involved consumer boycotts, usually involving alliances with religious communities and university students—as in the case of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers’ recent successful campaign against Taco Bell. When thinking about migrants as workers, one could reframe the spring 2006 events and note that they constituted the largest mass mobilization of workers of any kind in the history of the United States.

Spanish-language media also play a decisive role both in sharing information among migrants and creating pathways to engagement in U.S. society. There are three major national television networks that broadcast in Spanish along with dozens of local stations and cable channels, over three hundred radio stations, and over seven hundred newspapers. These media help address issues that matter particularly to migrants from Mexico and elsewhere in Latin America in a way that neither English-language nor home country media do (although migrants do use both of these extensively as well). The immigrant rights protests that took place in the spring of 2006 in cities throughout the United States showed the capacity of Spanish-language media to help mobilize millions of people. In many cities, radio hosts—many of whom engaged with civic issues for the first time—played a central role at generating mass interest among migrants in participating in these protests. In other cases, these media also provide information on voting, health campaigns, and issues in the educational system, among many other matters of concern to migrants. Some public media, such as Radio Bilingue, were specifically created to serve as an information source for migrants to share and address their concerns, and even mainstream Spanish-language media leaders tend to see this as part of their mission.

Despite extensive gains among Mexican migrants in civic engagement, their electoral participation in the U.S. remains very low compared to their overall numbers. The large number of undocumented migrants—perhaps half of all Mexican migrants—is only part of the reason. Even among those who are permanent residents and are eligible for citizenship, Mexican migrants naturalize at lower rates than that of immigrants of most other national origins. Low average levels of formal education appear to be key, but considering that 2.4 million Mexican legal permanent residents were eligible for citizenship in 2003, according to Department of Homeland Security data, remarkably little research on this issue has been carried out. We need to understand more about how immigrants make citizenship decisions, and whether Mexican permanent residents may face hidden barriers in the official naturalization process. For those who do become citizens, voter turnout rates tend to follow broader U.S. patterns in which lower levels of formal education and income are associated with lower turnout rates. Nevertheless, both citizen and non-citizen Mexican-born immigrants participate in politics in other ways, especially in local arenas, such as school boards, through unions, and through the work of many migrant-led organizations to shape city and state policies toward migrants. In the future, we need to pay attention to the impact of the recent wave of mobilization on other forms of civic and political engagement. Specifically, it will be important to observe to what extent these marches will lead to an increase in the interest of Mexican legal permanent residents in becoming full citizens with voting rights.

So far, Mexican migrants have also shown a low degree of formal engagement with Mexican elections as well. In 2005, the Mexican Congress for the first time allowed Mexicans abroad to register to vote in Mexico by absentee ballot. Only a little over one percent of those eligible registered for the 2006 presidential elections—though in international comparative terms, this is apparently normal for first-time diasporic voting. The low registration rate undoubtedly reflects, in part, the numerous procedural challenges involved in the complicated registration process; however, it also suggests that Mexican migrants, though in many cases proud to be able to vote in Mexican elections, may be more focused on immediate concerns in the communities where they live in the United States. More research is needed to disentangle motivations from obstacles. Nonetheless, the Mexican government has increased its ties to migrants abroad in other ways since the 1990s. This included the creation of the Institute for Mexicans Abroad in 2002, a governmental advisory group on policy related to migrant communities. Although the results of this process are mixed in terms of the Institute’s actual influence on policy decisions, it has certainly served to build a bridge between local migrant leaders and the Mexican government. The Institute’s membership, which is largely elected, also reflects a high degree of civic binationality, insofar as many of these leaders combine deep roots in U.S. civic, social and business organizations with strong ties to migrant organizations and to Mexico.

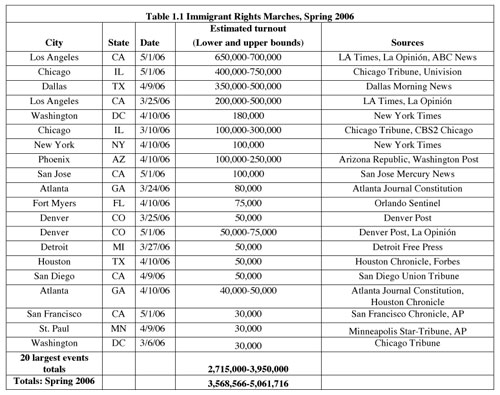

The overall panorama of Mexican migrant civic participation is in transition. It is notable that after the immigrant protests in dozens of U.S. cities in the spring of 2006 the mass media agreed that these were strictly peaceful protests—in notable contrast to the previous fall in France, for example. Migrants’ consistent repertoire of bounded protest reflected an extraordinary level of civic discipline, and was in large measure due to the vision of constructive engagement with the U.S. policy process that is shared by the key mobilizing institutions—churches, the media, community organizations and unions. Nonetheless, participation went far beyond these organizations and their members and drew in large numbers of migrants and their supporters who are not involved with formal organizations. In many cases the mobilizations were not only the largest immigrant rights protest in each respective city; in many cases they were the largest ever in each city’s history, as in Los Angeles, Phoenix, Chicago, Dallas, San Diego, Denver, Fresno, and San Jose and San Diego—not to mention the 75,000 in Ft. Myers, Florida (see Table 1.1, below).

As the number of Mexicans in the United States grows, they are both engaged with and reshaping U.S. civic life, as other immigrant groups have done in the past. Moreover, they are developing new forms of civic association that represent their own needs and interests. As so many immigrant groups have done in the past in this country, Mexican migrants begin their civic participation by helping their communities of origin and gradually translate these skills to participating in their communities of residence in the United States. Those who have the deepest sense of belonging in Mexico and strongest histories of engagement with their communities there are often the same people who develop the strongest claim to belonging in the United States and the most active forms of engagement in this country. Civic organizations, including churches and unions, and Spanish-language media play an important role in providing arenas where migrants’ voices are heard and their concerns shared and converted into actions. If the massive protests that brought millions of migrants into the street to push for immigration reform are any sign, the next decade may see a vast growth of Mexican migrant civic participation that further transforms and renews American civic life as other immigrant groups have done in the past.