On March 15, 2020, ignoring the Ministry of Health’s recommendations, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro paraded around Brasilia’s Monumental Axis Avenue with protesters who gathered against the Chamber of Deputies. Bolsonaro waved, greeted, and hugged protesters and spoke against the press, left-wing parties, state governors, and the opposition parties in the Chamber of Deputies who blocked his agenda. His supporters, dressed in the colors of the Brazilian flag, sang religious hymns and the national anthem. They called for military intervention. At that point, the Covid-19 pandemic was already in the news, and Brazil had around 200 cases. This political scene would be repeated throughout the next year. In addition to the common diatribes of Bolsonaro and his supporters against the Chamber of Deputies, opposition state governors, and the Supreme Federal Court (STF), the protests would take on increasingly dramatic tones in relation to Covid-19.

At the time of writing, Brazil’s Covid-19 numbers stand at around 664,000 dead and more than 30 million infected. The pandemic, and the countermeasures holding it at bay, have weakened the economy. According to data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), Brazil had 14.8 million unemployed in the first half of 2021. This political and economic situation has had lasting effects on how the pandemic unfolded since it revived and deepened disputes between supporters and opponents of Bolsonaro. In other words, the pandemic helped “throw more gas on the fire” of polarization.

Understanding how the pandemic affected an increasingly polarized political scene is fundamental to identifying the way political actors (inside and outside the state) have adapted and innovated ways of doing politics on the streets. Who were these political actors (pro- and anti-lockdown demonstrators)? How did these political actors innovate or adapt different tactical performances to overcome legal barriers to demonstrations in the time of Covid-19?

To answer these questions, this research cataloged protests that took place in public from March 1, 2020, to March 31, 2021, which were mentioned in national news, to reconstruct the confrontations between pro- and anti-lockdown political actors. The database comprises any public and collective actions that express discontent or support for social distancing measures or those of their formulators, supporters, or opponents in institutional spaces (e.g., politicians, bureaucracies, and judges). Additional material was also compiled from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) database.

“It’s just a little flu”: Covid’s political construction

“In some cities, like São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, political demonstrations were also banned in an attempt to contain the spread of the disease.”The first case of Covid-19 in Brazil was recorded on February 26, 2020, which coincided with Carnival. After the festivities, concern about the disease suddenly increased after the first death on March 17. That same week, the state government of São Paulo restricted activities in public areas. Following WHO recommendations, governors and mayors in other states implemented social distancing measures to contain the pandemic, a decision that received public support. In some cities, like São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, political demonstrations were also banned in an attempt to contain the spread of the disease. The STF ruled that governors and mayors had the authority to establish social distancing rules. This decision triggered right-wing claims that there was a “plot” against Bolsonaro and their constitutional freedoms. The theory among the “Bolsonarists” was that this would lead to a “communization” of Brazil carried out by Chinese interests, leading to the downfall of Western civilization.

On March 20, for example, right at the beginning of the pandemic, Senator Flávio Bolsonaro, son of President Bolsonaro, said on Twitter that those “who watched Chernobyl will understand what happened. Replace the nuclear plant with the coronavirus and the Soviet dictatorship with the Chinese. One more time a dictatorship preferred to hide something serious to expose the wear and tear that would save countless lives. China is to blame, and freedom will be the solution.”

The timing of the measures and the political crisis between the executive and other institutions created distrust over the supposed reasons behind the measures. Supporters of Bolsonaro questioned why Carnival had happened when the “supposed” pandemic was just beginning. The right-wing political press dubbed the media, universities, left-wing parties (especially the Workers’ Party or PT), and the center-right (known in Brazil as Centrão) dens of moral depravity and representatives of “crypto-communism.”

The pandemic on the streets: The waves of mobilization during Covid-19

Protests over the last two years have significantly decreased after the student movement manifestations and the demonstrations in support of Bolsonaro in 2019. During the pandemic, the first protests were by right-wing groups. Although small, this faction was already mobilized, which made it easier for them to take to the streets. On other hand, still affected by the 2016 impeachment of Dilma Rousseff (PT) and the arrest of former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva (PT) in 2018, the left was unable to build an agenda or broad coalition against Bolsonaro.

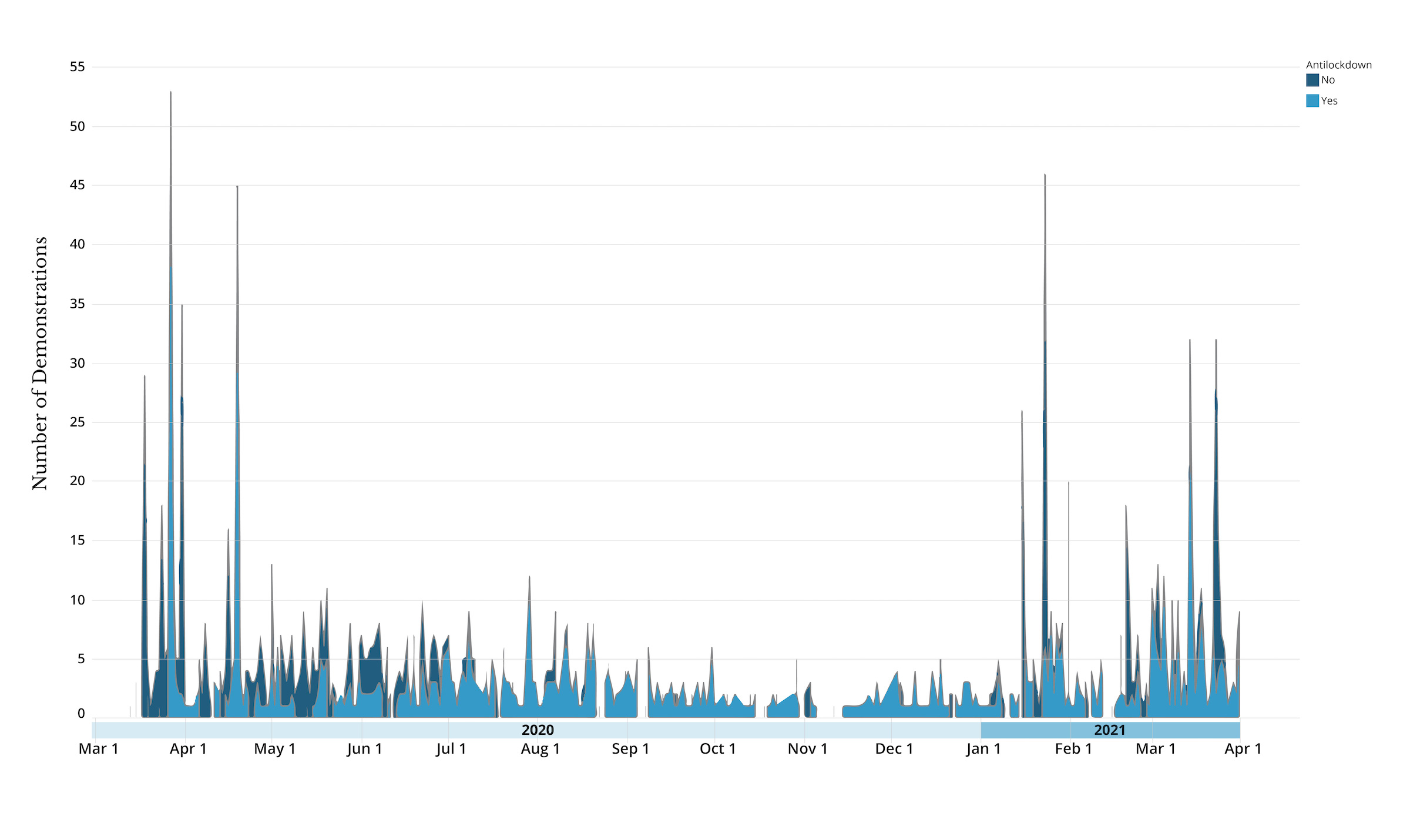

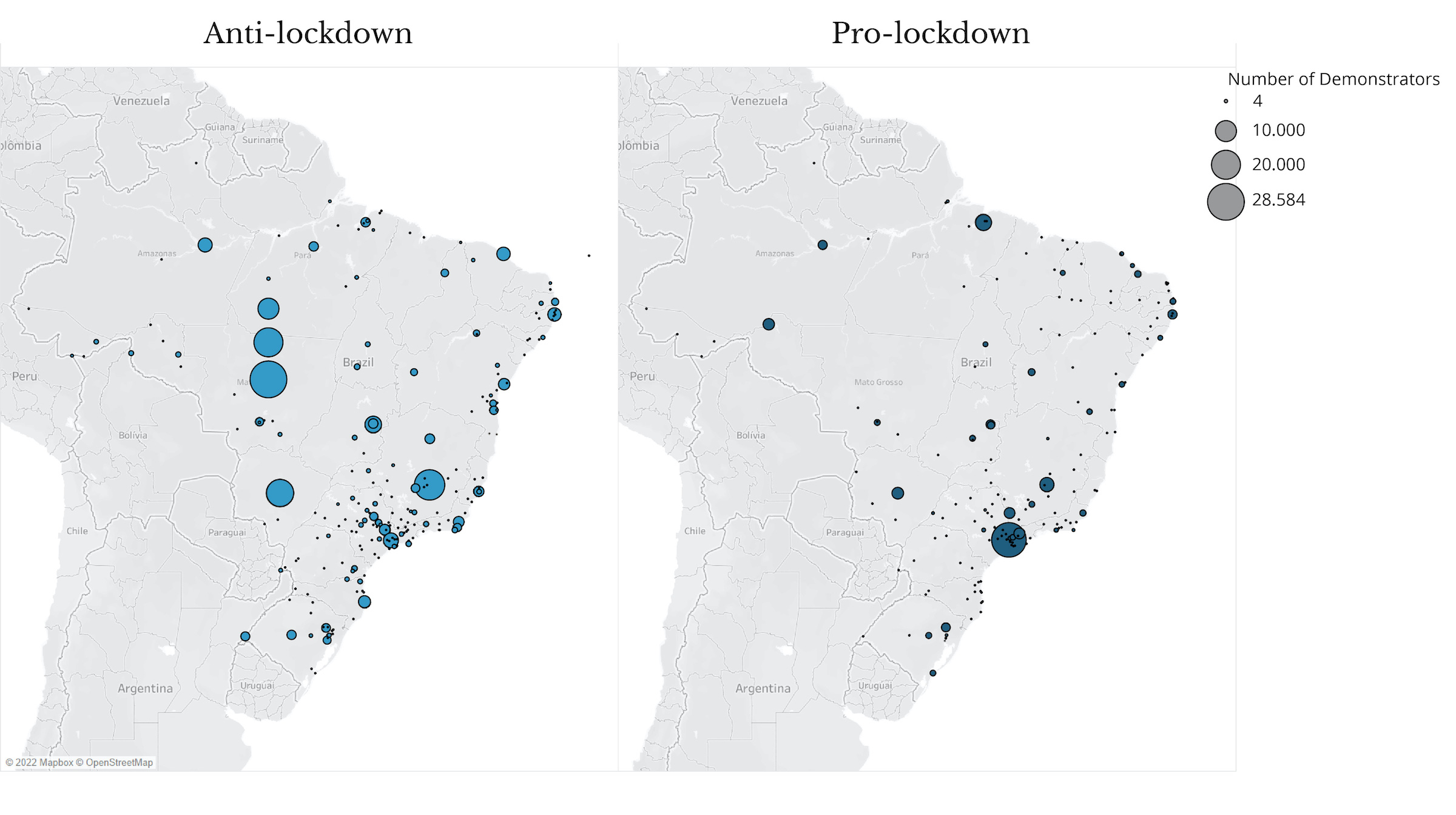

From March 13, 2020, to March 31, 2021, there were 1,751 protests, with an average of 4.7 events per day. Out of Brazil’s 5,570 municipalities, 328 registered events linked to Covid-19, most of them located in the southeastern and southern regions, which are the wealthiest areas in the country and contain the strongest support for the Bolsonaro government. The events were spread out over two great waves of mobilization. The first ran from approximately March 13 to May 31, 2020. It began with demonstrations in favor of Bolsonaro carried out by right-wing organizations, conservative digital influencers, and religious groups, and it ended with pro-lockdown organizers, left-wing parties, and antifascist groups in São Paulo rallying against the right’s “monopoly” over the street as a space of expression. During the first wave, both sides attempted to impose their agendas on the public sphere.

The second wave came in early January 2021 and stopped in July 2021. It began with the opposition’s attempt to retake the streets after serious allegations of corruption and interference in the management of the pandemic surfaced against the Bolsonaro government. In this phase, right-wing and far-right groups, through protests, rejected the re-introduction of social distancing measures to curb the second wave of Covid-19. Between these two peaks of mobilization came a period of supposed containment of the disease, after August 2020, and the street protests turned to mobilizations by professional groups affected by the economic crisis caused by Covid-19, but also by supporters of the president against the prolonged social distancing measures.

“Brazil above all”: The right-wing takes the streets

The first phase of mobilization was monopolized by Bolsonaro and his followers who opposed the Chamber of Deputies, the STF, governors, and mayors. The Bolsonarists called for protests against the supposed “dictatorship of little tyrants” represented by governors and mayors early in March and April. On March 27, they took to the streets in 53 cities to protest social distancing measures. A new pro-Bolsonaro peak came a few days later, on April 19, with a new demonstration against mayors and governors in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. In this first wave of protests, marches and rallies were the main tactics of expressing the anti-lockdown agenda. Local businessmen paraded down major thoroughfares of the capital cities of states whose governors opposed Bolsonaro, like São Paulo and Minas Gerais. There were also instances of violence against physicians and nurses, and cases of anti-isolation protesters planning attacks on Covid-19 hospitals. In June 2020, a political sit-in called the “300 of Brazil” was staged in front of the STF, calling for its closure, and days later they attempted to storm the National Congress. Dressed in Brazilian team jerseys and the national flag, these protests evoked the nationalist sentiments of mobilizations such as those that led to the impeachment of Fernando Collor in 1992 or Independence Day festivities. Requests for military intervention abounded during these occasions and throughout the year.

On April 19, 2020, for example, protesters gathered in front of the army’s headquarters in Brasília, calling for their intervention, welcoming the “end of rascality”—represented by the center-left and center-right and prevailing corruption—and reaffirming the “people in power.” The president paraded on top of a pickup truck and affirmed that there was no longer any reason to negotiate with Congress. After all, in his words: “Enough of the old politics. Now, Brazil is above all and God above all.” Bolsonaro followed this by participating in demonstrations and acts in favor of his own agenda more often. During this first wave, there were 949 protests against isolation and 806 against Bolsonaro and in favor of non-pharmacological measures, like social distancing rules and the use of masks. The main difference with the left-wing protests lies in the fact that a significant part of these protests took place in either virtual spaces or through pot-banging on balconies, which reduced their public visibility.

“The motorcades emerged as a winning tactic because they allowed for the ‘spectacularization’ of support for Bolsonaro in the face of free-falling poll numbers.”At the end of 2020 and the beginning of 2021, the anti-lockdown folks changed their strategy. After some direct attacks against Covid-19 field hospitals and sit-ins in front of the Chamber of Deputies and the STF, STF judge Alexandre de Moraes took measures to launch an inquiry into the assaults and fake news targeting Supreme Court members and to identify and arrest leaders of extreme right-wing groups. However, this response backfired, and anti-lockdown protesters managed to create another route for mobilizations: motorcades. These demonstrations first appeared as a timid attempt to circumvent restrictions on the use of public space but ended up propping up the narrative that Bolsonaro’s fall in popularity, as recorded by research institutes, was actually “fake news” and a “hoax.” Motorcades supplanted other protest forms, such as sit-ins and demonstrations in front of hospitals and public services, marches, and rallies. The motorcades emerged as a winning tactic because they allowed for the “spectacularization” of support for Bolsonaro in the face of free-falling poll numbers. This spectacularization was carried out with the intention of making support for Bolsonaro appear bigger than it really was. Flags, anthems, songs, and slogans were shouted at these marches to magnify support for the president and to turn Bolsonaro into some sort of “savior of the homeland” against the “pandeminions,”1In Brazil, the movies Despicable Me and Minions were huge successes. The term “minion” has entered the political vocabulary as a derogatory synonym for “blind supporter or follower.” For example, “bolsominions” is the word used by left-wing groups for fanatic supporters of Bolsonaro. i.e., supporters of social distancing.

“No oxygen, no vaccine, no government”: The opposition strikes back

Initially, the opposition against Bolsonaro opted for pot-banging protests. The strategy had been used successfully by right-wing groups during Rousseff’s impeachment. During the pandemic, this strategy was used when the president made statements on primetime television against social distancing measures. On March 17 and 18, 2020, the first pot-banging protests happened in large Brazilian cities. The use of laser projections on buildings was also common during this first phase of opposition protest, including the usual “Out Bolsonaro” (“Fora Bolsonaro”) messages and new ones calling him a “Killer” and “Science Denier.”

But the pot-banging demonstrations didn’t last long. Their concentration in middle-class neighborhoods undermined their efficacy and visibility. The lack of visibility of the pot-banging protests due to social distancing measures, and the difficulty of building a coalition that combined left-wing groups, such as political parties and social movements, with former supporters of Dilma’s impeachment made the pro-lockdown folks lose the streets to right-wing agitators. In 2020, in small and medium-sized cities in the countryside, protesters emulated religious processions, carrying crosses to commemorate Covid-19 victims. Although small and uncoordinated, these protests were well-reported in the press, making the mourning visible and emphasizing the feeling of outrage toward the federal pandemic policy. Without relying on the resources of professional groups and businessmen, the left coalition tried to innovate by adopting tactics that did not prioritize the taking of the streets as the main tactic.

The reaction against the anti-lockdown protesters came in May 2020 with campaigns organized by organized soccer fans, antifascist groups, and leftist parties who sought to retake the streets with protests in large urban centers such as São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte, and Porto Alegre. Inspired by the protests of the US #BlackLivesMatter movement, on May 31, protesters dressed in black and under the slogan “In defense of democracy and against fascism,” marched on Avenida Paulista, São Paulo’s main avenue, at the same time as a pro-Bolsonaro demonstration was taking place. A clash between the two groups erupted and the police had to intervene. Another common form of mobilization at this time was the vigil or other acts of mourning. Also, on May 31, healthcare professionals took to the streets in Belo Horizonte to protest the current public health policy and ask for Bolsonaro’s departure from the presidency.

“Since March 2021, opposition groups have been trying to build strategies based on mass mobilizations supported by leftist parties, unions, social organizations, grassroots groups, and health professional associations.”As accusations of corruption against Bolsonaro’s government mounted and the second wave escalated, left and center-left groups, civil society, and former political enemies began to discuss the creation of a coalition. On January 15, 2021, the pot-banging returned to major cities with people chanting, “No oxygen, no vaccine, no government.” In the same month, leftist parties, unions, and social movement organizations borrowed the tactic of the motorcade and organized parades in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. At the same time, center-right social movements that had backed Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment—the Free Brazil Movement (Movimento Brasil Livre) and Movement “Come to the Streets” (Movimento Vem pra Rua)—helped launch the manifesto “Brazilian Lives Matter.” Since March 2021, opposition groups have been trying to build strategies based on mass mobilizations supported by leftist parties, unions, social organizations, grassroots groups, and health professional associations. On May 29, for example, 180 cities across the country participated in a demonstration against Bolsonaro.

The contentious pandemics: The dangers of ongoing polarization

Protests do not occur in a vacuum and the pandemic was not only a public health problem. The pandemic could have ended the repeated use of the streets as an arena of expression. This is because, before the arrival of vaccines, the measures to contain the virus were restricted to social distancing and the use of masks. These measures directly interrupted cities’ routines and hindered the gathering of crowds and other forms of occupying public spaces.

However, the pandemic did not reverse the trends of continued mobilization in the streets. Covid-19 did not curb street politics, as different political actors had the pandemic as a focal point for their agenda. Adding to the pandemic context, the political and economic crisis and the continued polarization have, therefore, helped to promote a dynamic of mobilizations and counter-mobilizations, protests and counterprotests in the streets. On the one hand, the pandemic offered the pro-Bolsonaro side the opportunity to build a narrative to deepen its attack on opponents. The president’s supporters attempted to help Bolsonaro “govern” through the streets, demonstrating strength and numbers at a time of declining political support in opinion polls. On the other hand, Covid-19 represented a set of important losses for various social sectors and helped intensify Bolsonarism as the main target of various political groups on the left and center-left. In this context, these activist groups mobilized several performances of claim-making in public space: rallies (and later the famous motorcades), pot-banging protests, blockades, public assemblies, and marches.

In Brazil, disagreements over the best measures to be adopted regarding the control of the Covid-19 pandemic led to the deepening of political cleavages. Those in favor of early pharmacological treatments for the disease—for example, the use of hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin—built coalitions with small business owners and occupational groups negatively impacted by antivirus policies. This accumulation of resources helped promote and fund motorcades, marches, crowds, and performances that challenged Covid-19 measures. On the other hand, supporters of social distancing and vaccination did not have the same financial backing. This produced a dynamic of mobilization in which creative protest strategies, such as pot-banging, ceremonies, and theatrical performances, gained space.

The polarization won’t stop soon. As the stage of a political drama, the streets have served as a location for expression and democratic representation but also to challenge scientific consensus. The use of protests as a strategy to promote government ideology and unrestricted support for the science deniers’ agendas from sectors of the state is worrisome. The Brazilian case brings important reflections to the relationship between crisis, street politics, and democracy since Brazil was one of the epicenters of the pandemic and one of the most relevant conflict scenarios facing the challenges imposed by Covid-19. Some analysts argue that abrupt institutional ruptures or confrontations are unlikely, but there is no doubt that the ongoing polarization will have serious consequences for Brazil’s future.

Banner photo: Marília Castelli/Unsplash.