Personal support workers (PSWs) provide a significant amount of the frontline health work that occurs in public and private care settings in Canada. As essential workers, employment of PSWs has continued through the Covid-19 pandemic, in settings that are highly susceptible to community spread and ill-equipped to deal efficiently with coronavirus testing, prevention, and intervention responses. While PSW labor was already highly precarious prior to the pandemic due to low wages, predominantly contract and part-time employment, and non-optimal working conditions, the Covid-19 pandemic has magnified the precarious aspects of PSW work and thereby increased the vulnerability, exploitability, and invisibility of PSWs. For example, the work of PSWs has become even more invisible as many long-term care facilities have been preventatively locked down, thereby becoming inaccessible to all but essential workers.

“The PSWs who participated in the project created a photovoice…to exhibit their personal narratives, raise critical consciousness, and engage with a larger community, thus facilitating agency and the potential for positive structural change.”This project examines the experiences of PSWs in Ontario, Canada, to explore the impact that the Covid-19 pandemic has had on their labor and personal conditions using a community-based and critical arts-based approach to inquiry.1 New York: Routledge, 2018More Info → The PSWs who participated in the project created a photovoice—a form of community-based storytelling using images—to exhibit their personal narratives, raise critical consciousness, and engage with a larger community, thus facilitating agency and the potential for positive structural change. Key findings from this project center around the precarity in the work of PSWs that was magnified by the pandemic and characterized by unsafe working conditions, exploitation, precarity, and a lack of autonomy. Another key finding is the sense of loss and burnout among PSWs, due to the limited methods of care resulting from Covid-19 healthcare protocols that restricted touch and close contact. This experience of precarity was specific to the pandemic, and PSWs felt a vulnerability and a grief that was mirrored in the people they were caring for.

New York: Routledge, 2018More Info → The PSWs who participated in the project created a photovoice—a form of community-based storytelling using images—to exhibit their personal narratives, raise critical consciousness, and engage with a larger community, thus facilitating agency and the potential for positive structural change. Key findings from this project center around the precarity in the work of PSWs that was magnified by the pandemic and characterized by unsafe working conditions, exploitation, precarity, and a lack of autonomy. Another key finding is the sense of loss and burnout among PSWs, due to the limited methods of care resulting from Covid-19 healthcare protocols that restricted touch and close contact. This experience of precarity was specific to the pandemic, and PSWs felt a vulnerability and a grief that was mirrored in the people they were caring for.

Precarity

The term precarity has been closely critiqued in recent years for its analytic utility. Following the theoretical work of Bourdieu,2 Polity Press, 1998More Info → precarity has been conceptualized as a structure of neoliberal discourses and practices that fosters a sense of insecurity based upon a premise of scarcity, which has engendered a cycle of exploitation, consumption, resource depletion, and surveillance. Under this conceptualization, material aspects of individual, community, and national existence are determined by one’s location in the market and the precarity of that location. Another conceptualization of precarity brings an existential consideration forward: We are all precarious, as a matter of existence, and vulnerable to loss, suffering, hardship, and unpreparedness. According to critical feminist theorists like Butler3→Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (Verso, 2004).

Polity Press, 1998More Info → precarity has been conceptualized as a structure of neoliberal discourses and practices that fosters a sense of insecurity based upon a premise of scarcity, which has engendered a cycle of exploitation, consumption, resource depletion, and surveillance. Under this conceptualization, material aspects of individual, community, and national existence are determined by one’s location in the market and the precarity of that location. Another conceptualization of precarity brings an existential consideration forward: We are all precarious, as a matter of existence, and vulnerable to loss, suffering, hardship, and unpreparedness. According to critical feminist theorists like Butler3→Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (Verso, 2004).

→Judith Butler, “Bodies in Alliance and the Politics of the Street,” Transversal 9 (2011): 1–29. and Puar,4Jasbir Puar, “Precarity Talk: A Virtual Roundtable with Lauren Berlant, Judith Butler, Bojana Cvejić, Isabell Lorey, Jasbir Puar, and Ana Vujanović,” TDR: The Drama Review 56, no. 4 (2012): 163–177. such an acknowledgment of precarity can draw us together in response to one another’s vulnerability and in acknowledgment of the collective capacity to address hardship and suffering. We can see ourselves as part of a web of connections and resources. Some of these resources are infinite, such as human agency, and can be used to address and resist the unjust depletion of finite resources.

Critical arts-based photovoice research

Critical arts-based approaches have the capacity to counter the impact of a dominant discourse that generalizes the identities of personal support workers while normalizing their experiences. For example, a dominant discourse describes personal support work as unskilled, nonprofessional labor, rather than questioning the prevalence of women of color in these insecure, low-paying positions. Critical arts-based approaches can center subjective experiences in order to amplify narratives that challenge the dominant discourse and status quo. The use of critical arts-based research can support social change through the counternarratives that are produced with creativity, valued subjective expression, and the resistance to standard forms of research that are premised by dominant discourses.5Gwenda van der Vaart, Bettina van Hoven, and Paulus P. P. Huigen, “Creative and Arts-Based Research Methods in Academic Research. Lessons from a Participatory Research Project in the Netherlands,” FQS 19, no. 2 (2018).

Photovoice is an arts-based approach significant in its capacity to center the voices of community members.6Genevieve Creighton et al., “Photovoice Ethics: Critical Reflections from Men’s Mental Health Research,” Qualitative Health Research 28, no. 3 (2018): 446–455. Community-immersed photovoice featuring subjective stories has the potential to reveal counternarratives to a dominant discourse that communicates the precarity of identities, experiences, and labor. Photovoice involves storytelling and images. Images are created to represent a story that has been invited to be told, shared, and facilitated as part of the research process. Photovoice research calls upon deep and participatory community engagement, as well as an elicitation process that calls upon critical reflection to support critical consciousness-raising.7Nicole L. Thompson, Nicole L. Miller, and Ann F. Cameron, “The Indigenization of Photovoice Methodology: Visioning Indigenous Head Start in Michigan,” International Review of Qualitative Research 9, no. 3 (2016): 296–322.

Using a photovoice approach, we engaged with 15 PSWs in Ontario, Canada, in a critical exploration of their experiences working through Covid-19, paying particular attention to feelings of precarity. These discussions painted a stark picture of the precarity PSWs encounter during the Covid-19 pandemic, centering around risk, vulnerability, and the stigma associated with old age, disability, and ill-health. Considering that the dominant discourse reproduces and amplifies the precarity of identities, experiences, and labor, community-immersed photovoice that features subjective stories is a particularly meaningful method of exploration with the potential to reveal powerful counternarratives.

“We hosted two virtual gatherings, where PSWs were invited to see one another’s images and share their reflections.”We began our project by virtually interviewing each PSW, inquiring about how their work and personal lives had been impacted by Covid-19. We asked about different aspects of precarity: exploitation, invisibility, and insecurity. We also asked PSWs to take a photograph of something that could reflect what had stood out for them in our interview. In a second interview, we included an artist to collaborate with the PSW. The artist used Photoshop to enhance the image to clearly represent what the PSW wanted to express. With the completed photovoice image, we reconnected with each PSW and worked with them to develop a title and artist statement. Finally, we hosted two virtual gatherings, where PSWs were invited to see one another’s images and share their reflections. During these gatherings, we also brainstormed ways to mobilize the photovoices. We created a project-specific Instagram account to post the photovoice images and artist statements from those who wanted to be included.

The interviews, photovoice images, and artist statements reflected the personal narrative of each PSW in a way that raised critical consciousness. Furthermore, the project created opportunities for engagement with a larger community, through social media and community presentations of the images and artist statements. The engagement also occurred when the PSWs gathered together and shared their reflections with one another. With their photovoice images, some of the PSWs described their racialized experience, in terms of the kinds of relationships they had with coworkers within a healthcare setting. In dialogue with other PSWs about each other’s photovoice images, they were able to share stories about unsafe work conditions, low wages, and the lack of benefits within the context of their gendered and racialized experience. The critical consciousness that occurred was enhanced by the dialogue where PSWs located their personal experiences into a larger context of structures of inequity that impact race, class, and gender in specific ways.

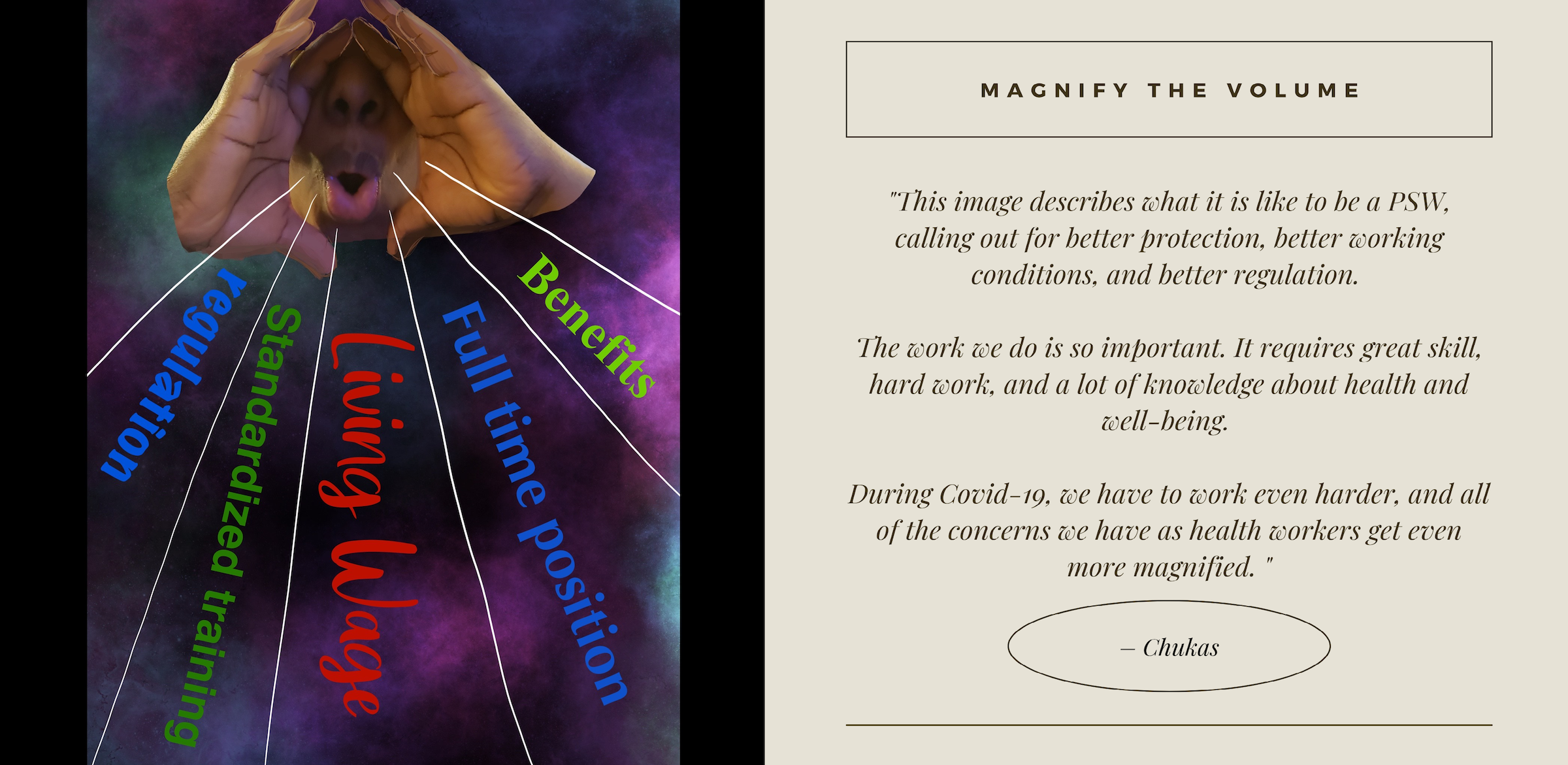

Precarious work and the desire to care

We used a qualitative thematic analysis8Thematic analysis is a form of qualitative data analysis, which involves reading through interview transcripts and identifying elements and patterns within the data. with the interviews. The photovoice images represented the important aspects of each interview and were incorporated into the later stages of thematic coding. The stories described a precarity that was related to race, citizenship/documentation, gender, and class. The PSWs were immigrants, racialized individuals, women, and/or underemployed individuals who described how they were caught in the lower rungs of a hierarchy that organizes international labor and economic relations as well as institutional and personal work relations. In these positions that are low on social and economic hierarchies, the PSWs experienced diminished human rights and injustice through (1) a lack of access to safe working conditions; (2) exploitation as reflected in low wages, few if any benefits, and unfair labor expectations; (3) precarity through a lack of meaningful recognition and voice, lack of job security, and changes (often significant diminishment) in employment opportunities (Figure 1); and (4) a lack of autonomy experienced through criminalizing surveillance methods within their work settings, an overall lack of control, and the limited ability to make work-related choices. This research, with the collection of the PSW stories, demonstrates the layers of precarity, from international relations to employment settings to the mundane moments in a typical workday. One significant finding is that precarity is well-established in the lives of the PSWs and was simply magnified by Covid-19.

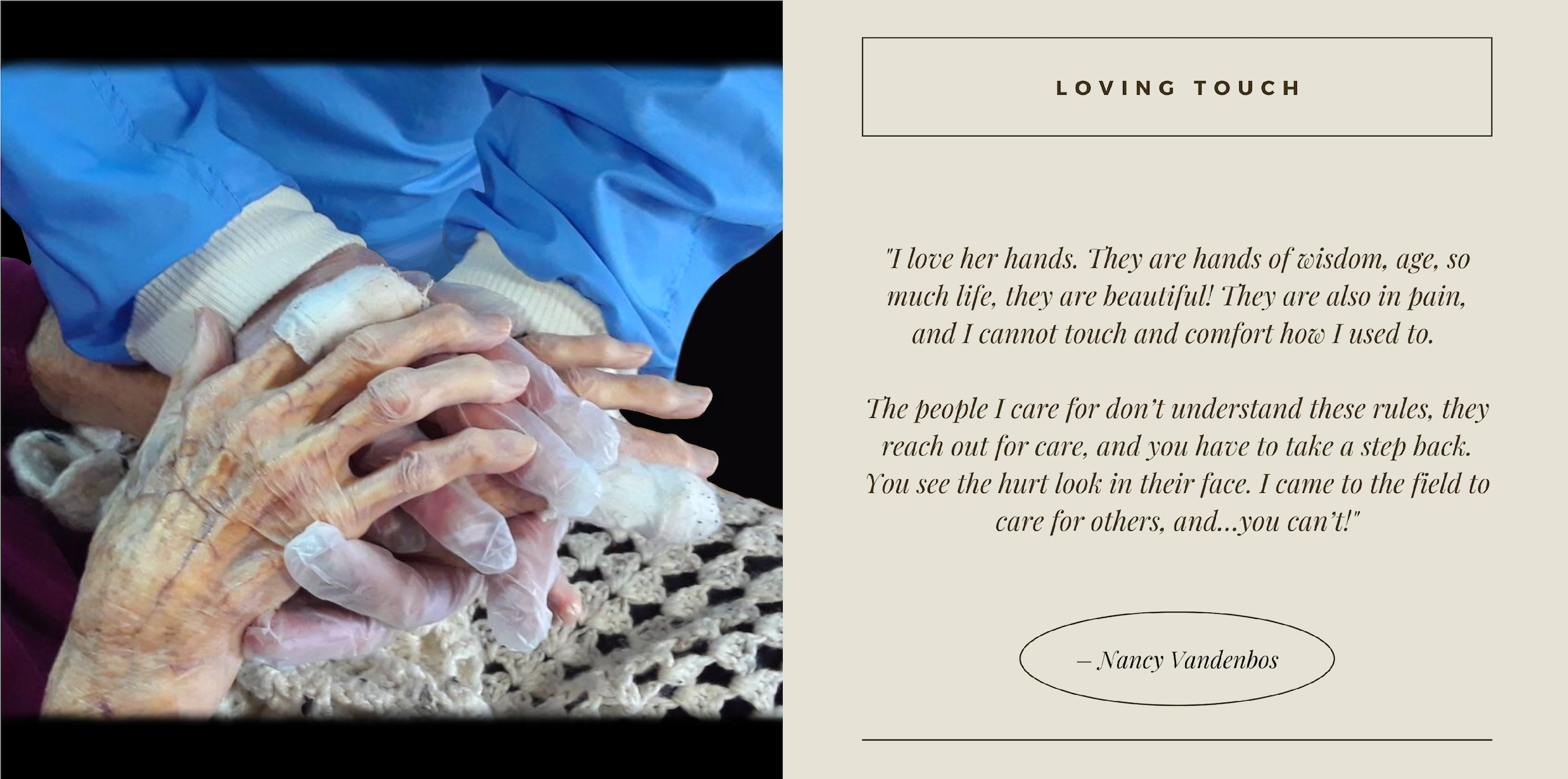

Another precarity that the PSWs described was specifically related to and influenced by Covid-19. The PSWs described a strong ethic of care as they talked about their relationships with clients and the losses they experienced because they could no longer care in the ways they wanted, such as through touch (Figure 2). They also could empathize deeply with the loss and depression that their clients were experiencing due to the measures of caring from a distance, and some PSWs described feelings of burnout, as they struggled to find meaning in their altered care work. This precarity was brought about by the vulnerability of human lives that had brought the PSWs to the field of health, a vulnerability that was magnified by the risks and accompanying protocols of a life-threatening contagious disease. Their usual response to vulnerability was to care through touch, physical tending, and close proximity. The restrictions to these approaches of care and the socially distanced alternative care methods created a significant loss for the PSWs, to the extent that they struggled to keep a sense of meaning in their work. They witnessed the fear, vulnerability, and confusion in the people they cared for, and they were helpless to respond in the ways that made the most sense to their ethic of care.

PSW voices: Implications for networks and collective action

The layers of injustice and inequity that are woven into the precarious labor market become more apparent in times of crisis: in the case of this study, the crisis of an international pandemic. A large number of the PSWs described an important response to be one of solidarity: how to organize PSWs formally and informally in order to protect their human rights. In consideration of their heightened vulnerability, PSWs expressed a need to gather together, as a collective response to hardship.

“PSW narratives need to be told, and we as policymakers, service providers, community members, and fellow health workers need to listen and learn.”We believe the implications of these findings is that such solidarity needs to be supported and collaborative, so networks can be built with allies and partners. The challenges, concerns, and struggles that the PSWs described touch upon a number of social issues that are being addressed by other groups and individuals. For example, the concerns related to the exploited labor of migrant workers are addressed by various action groups and agencies, such as migrant workers centers, workers’ rights groups, local politicians, patient advocate associations, equity advocates, and more. We suggest that solidarities be initiated and built by PSWs and also by these potential partners to collectively mobilize effective and just policy development that will improve the labor conditions for PSWs. At the same time, as the PSWs described the limits imposed by social distancing on forms of care, such as touch and the increased vulnerability of themselves and the people they care for, we believe a collective acknowledgment of grief and loss should occur. PSW narratives need to be told, and we as policymakers, service providers, community members, and fellow health workers need to listen and learn. When PSW voices are strengthened and validated, there are opportunities to address labor injustice. There are also opportunities to respond with relevant support to the widespread loss and trauma that PSWs have experienced while working through Covid-19.

In featuring the voices of PSWs, the photovoice project brought to the fore injustices related to precarious labor in the health services field, magnified by the Covid-19 pandemic. Work conditions worsened for PSWs (increased hours/overtime, increased scrutiny, lack of access to personal protective equipment [PPE]), leading to exhaustion brought about by extreme demands and expectations with inadequate compensation, security, and recognition. Additionally, we learned about the ethos of care that many PSWs bring to their work, characterized by a deep commitment to relationship, to the wellbeing of those they care for, and to the personal integrity with which they enter the health field as service providers. The harsh conditions and protocols of precarious health work during a pandemic enforced restrictions (such as social distancing) to the caring activities that PSWs engage and find meaning in, and PSWs can begin to feel disconnected from the meaning that they derive from their health work. A cycle is created between exhaustion and burnout. We contend that this cycle needs to be broken, and can only be broken by addressing, in a coordinated and collective manner, the multiple layers of injustice and grief that are reproduced through precarious labor conditions.

References:

→Judith Butler, “Bodies in Alliance and the Politics of the Street,” Transversal 9 (2011): 1–29.