The mass shooting in Atlanta on March 16 catapulted anti-Asian violence and hate onto the national spotlight. On that day, a 21-year-old White man murdered eight people in three massage parlors, including six Asian immigrant women: two of whom were Chinese, and four, Korean. Working low-wage jobs that required not only their physical presence but also their physical touch during a global pandemic, their lives laid bare the vulnerabilities at the intersection of race, gender, class, nativity, and citizenship.

Their lives may seem remote and unconnected to mine, but as an Asian woman, an immigrant, and a daughter of Korean immigrant entrepreneurs, I know that my fate is intimately connected to theirs.

The horrors of the deadly massacre elicited a rallying cry that something must be done, but for Asian Americans—76 percent of whom had been worried about anti-Asian violence, harassment, and discrimination since last summer—this cry is a year overdue. Between 2019 and 2020, hate crimes decreased by 7 percent nationwide, but increased by 150 percent against Asians. Zeroing in on New York City, there were three recorded hate crimes against Asians in 2019. By 2020, the number jumped nearly tenfold to 28, and in the first three months of 2021, the number has skyrocketed to 35.

Responding to the rise in anti-Asian hate, Asian American community leaders created the website Stop AAPI Hate for victims to safely and anonymously report hate incidents in English or 11 Asian languages. Within the first 24 hours of the website’s launch in March 2020, 40 incidents were reported. To date, they have received close to 4,000, two-thirds from women.

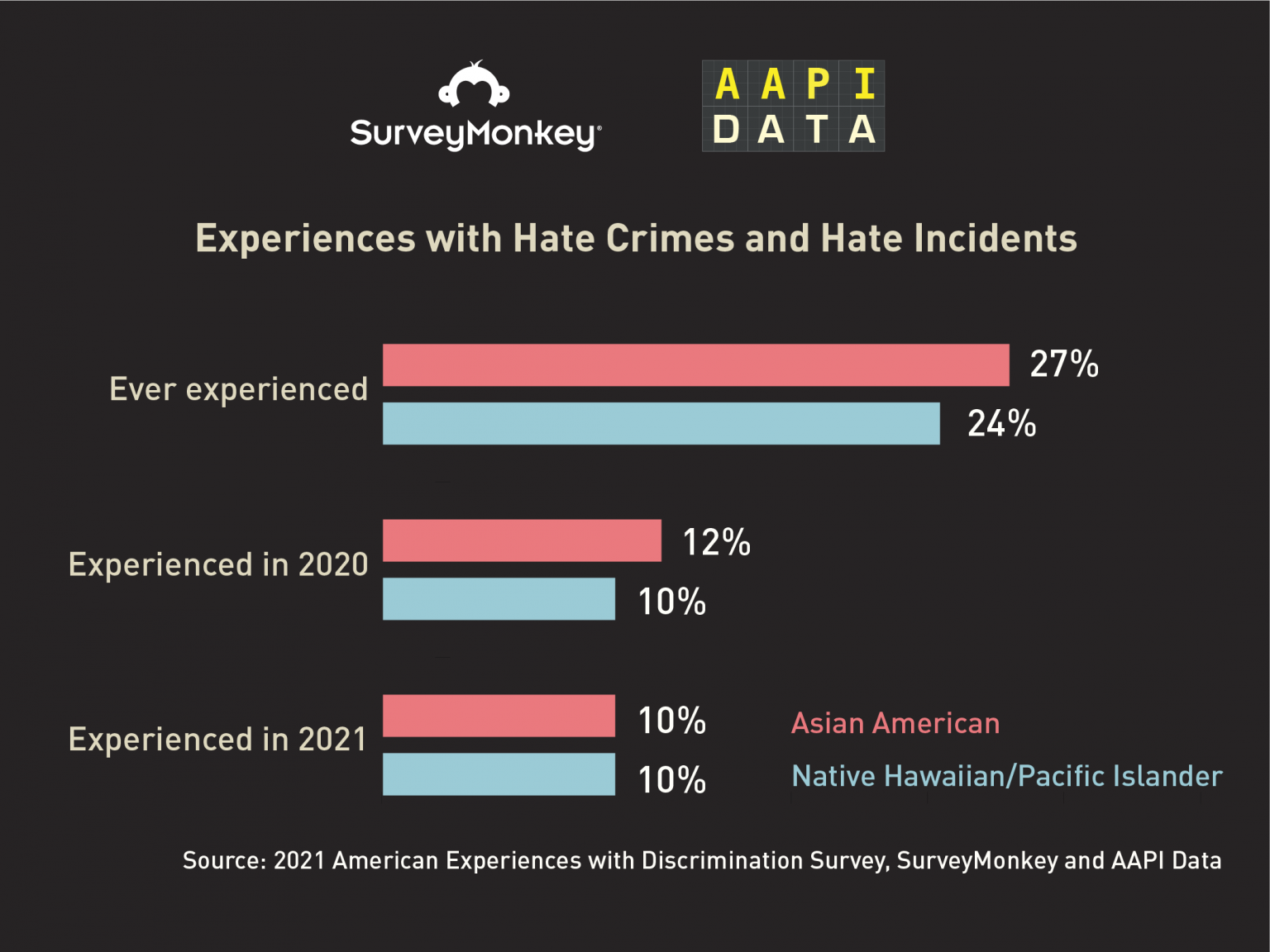

Self-reported hate crime data reflect, however, only a thin slice of all hate incidents against Asians. Missing are the cases that go unreported and unrecorded. Recognizing the need for more accurate data, AAPI Data partnered with SurveyMonkey to field a national survey immediately after the mass shooting in Atlanta. The findings confirmed what researchers at AAPI Data suspected: Anti-Asian hate incidents are far more numerous and affect a larger swath of the US Asian population than earlier accounts suggest.

Since March of last year, upwards of 2 million Asian American adults have experienced an anti-Asian hate incident, including 1 in 8 Asian American adults in 2020, and 1 in 10 in the first three months of 2021 alone.1The respondents were asked, “Have you ever been a victim of a hate crime? That is, have you ever had someone verbally or physically abuse you, or damage your property specifically because of your race or ethnicity?” If they answered “Yes,” then they were asked three additional questions about whether they experienced hate crimes or hate incidents “before the coronavirus pandemic in 2020,” “last year, in 2020,” and “this year, in 2021.” As sheltering-in-place orders are lifted across the country, it is not unlikely that we may see a spike in hate incidents against Asians.

For many observers, these attacks are a result of Trump’s anti-Asian rhetoric, and, more specifically, his persistence in blaming China for the origin and spread of Covid-19, along with repeated reference to the coronavirus as the “China virus,” the “Chinese virus,” and “kung flu.” Research shows that non-Asian Americans exposed to the “China virus” rhetoric were more likely to perceive Asian Americans as foreign and un-American, which can lead to greater hostility toward them.2Sean Darling-Hammond et al., “After ‘The China Virus’ Went Viral: Racially Charged Coronavirus Coverage and Trends in Bias Against Asian Americans,” Health Education and Behavior 47, no. 6 (2020): 870–879.

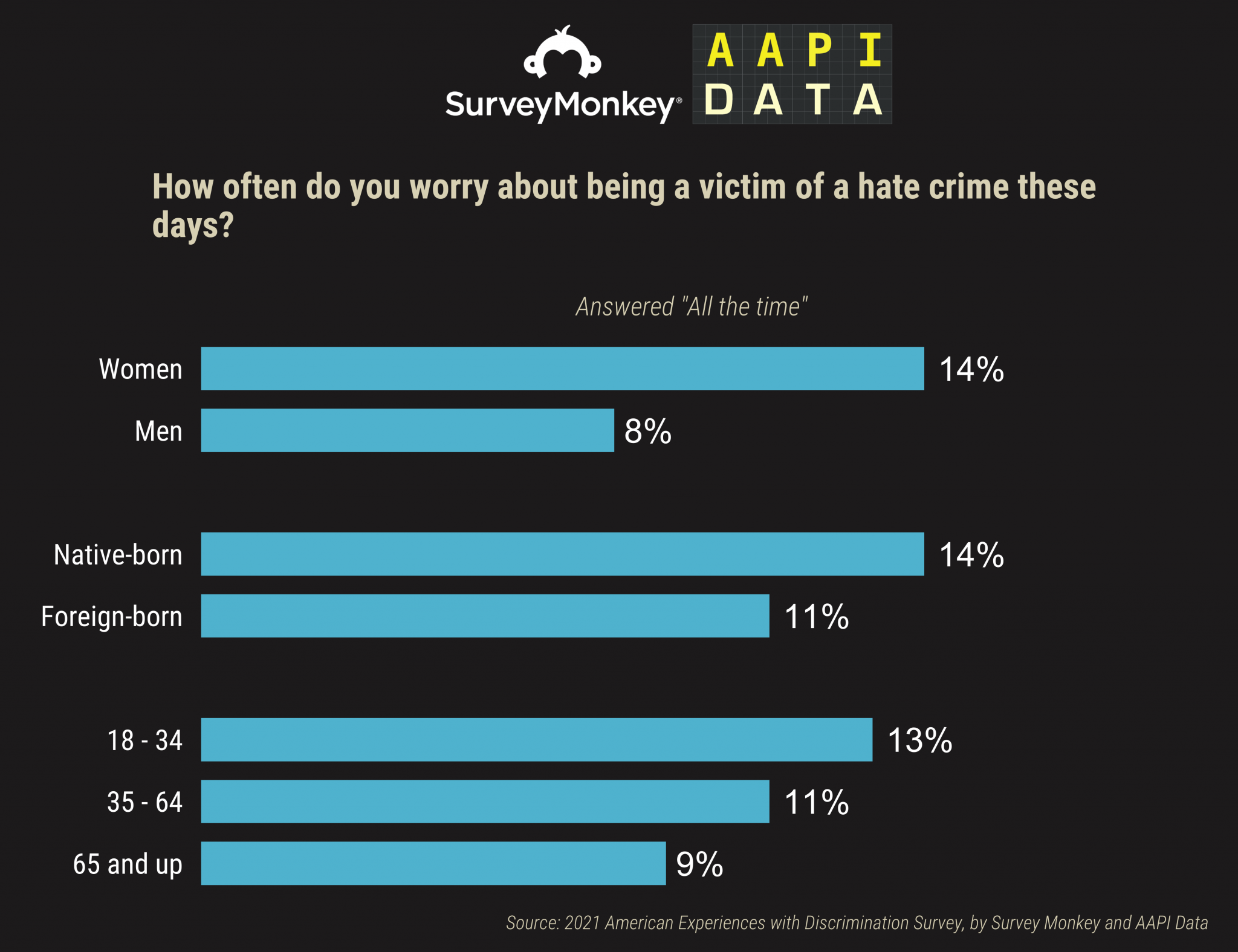

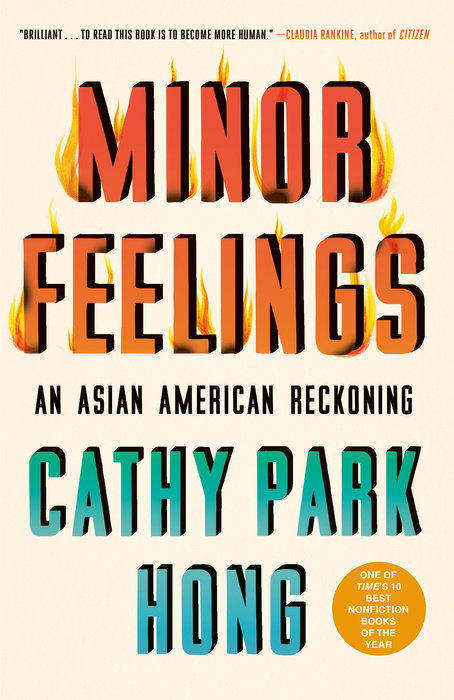

In the US context, the ethnic targeting of Chinese people extends to the racial targeting of Asians, as Chinese is a “synecdoche for Asians the way Kleenex is for tissues,” as poet Cathy Park Hong writes.3 NY: Penguin Random House, 2021More Info → In addition, as Viet Thanh Nguyen and Janelle Wong remind us: “Most Americans are not skilled at distinguishing between people of different Asian origins or ancestries, and the result is that whenever China is attacked, so are Asian Americans as a whole.” Hence, the majority of Asian Americans—regardless of ethnicity—worry about being the victim of a hate crime, including 68 percent of Southeast Asians and 58 percent of South Asians. The concern is especially acute among women, US-born Asians, and young adults—one in seven of whom worry all the time.

NY: Penguin Random House, 2021More Info → In addition, as Viet Thanh Nguyen and Janelle Wong remind us: “Most Americans are not skilled at distinguishing between people of different Asian origins or ancestries, and the result is that whenever China is attacked, so are Asian Americans as a whole.” Hence, the majority of Asian Americans—regardless of ethnicity—worry about being the victim of a hate crime, including 68 percent of Southeast Asians and 58 percent of South Asians. The concern is especially acute among women, US-born Asians, and young adults—one in seven of whom worry all the time.

A legacy of bigotry, violence, misogyny, and exclusion

While Trump’s racist slurs intensified bigotry toward Asians, it would be a mistake to reduce anti-Asian hate to Trump’s rhetoric alone. Even before the pandemic, hate crimes against Asians under the Trump administration increased 31 percent between 2016 and 2018. Most significant, bigotry, violence, misogyny, and exclusion against Asians are deeply ingrained in US history. Scapegoated as economic threats, sexually aberrant disease carriers, and threats to a free White republic, Asians have been targets of violence for more than 150 years.

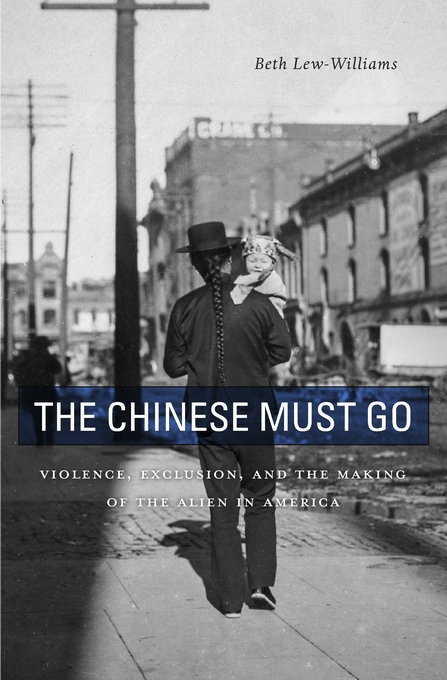

One of the largest mass lynchings in US history took place in Los Angeles in 1871, when 19 Chinese residents—10 percent of the city’s Chinese population at the time—were killed by a White mob. In 1885, the US West erupted in anti-Chinese violence, with taunts that “The Chinese Must Go,” as Beth Lew-Williams powerfully details.4 Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018More Info → In the Rock Springs Massacre, for example, White miners killed 28 Chinese workers, wounded 15, and expelled hundreds more before setting fire to their living quarters.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018More Info → In the Rock Springs Massacre, for example, White miners killed 28 Chinese workers, wounded 15, and expelled hundreds more before setting fire to their living quarters.

Anti-Asian violence was coupled with legal exclusion and misogyny. In 1875, the Page Act was introduced to outlaw “immoral Chinese women” based on the claim that they were all prostitutes, becoming the first federal exclusionary law in the United States. By categorizing Chinese women as lewd vectors of venereal disease, and threats to White manhood, morality, bloodlines, and health, this early law helped institutionalize the sexualization, objectification, and vilification of Asian women. The legacy of this past continues to haunt the present, which became fatally clear when a self-professed White male sex addict sought to eliminate the objects of temptation by murdering the six Asian women in Atlanta. “Hatred does not preclude desire,” as Anne Anlin Cheng poignantly reminds us, “Hatred legitimizes the violent expression of desire.”

The Page Act resulted in a grossly imbalanced gender ratio of 21 Chinese men for one Chinese woman by 1880. Without their wives, male Chinese laborers who helped build the transcontinental railroad were segregated into tight-knit bachelor communities that became the precursors of today’s Chinatowns. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act evolved from the earlier Page Act, and would last six decades until 1943. The nativist bigotry that White settlers imparted, and the discrimination that Chinese endured, shaped societal perceptions of the Chinese in the nineteenth century as economic and sexual threats, clannish, untrustworthy, foreign, and immoral disease carriers.

Subhuman, suprahuman, but not human

The US legacy of violence, misogyny, and exclusion against Asians coupled with what Marie Myung-Ok Lee describes as the US military’s long history of the systematic dehumanization of Asians are only some of the horrors that continue to mark both Asians and Asian Americans as foreign and subhuman. The change in US immigration law in 1965 ushered in a new stream of highly educated, hyperselected immigrants from Asia5 Russell Sage Foundation, 2015More Info → that propelled the racial mobility of Asians from subhuman to suprahuman.6Jennifer Lee, “Asian Americans, Affirmative Action & the Rise in Anti-Asian Hate,” Daedalus (Spring 2021). Whether subhuman or suprahuman, however, Asians are not perceived as just human, thereby marking them as a foreign, un-American “other.”

Russell Sage Foundation, 2015More Info → that propelled the racial mobility of Asians from subhuman to suprahuman.6Jennifer Lee, “Asian Americans, Affirmative Action & the Rise in Anti-Asian Hate,” Daedalus (Spring 2021). Whether subhuman or suprahuman, however, Asians are not perceived as just human, thereby marking them as a foreign, un-American “other.”

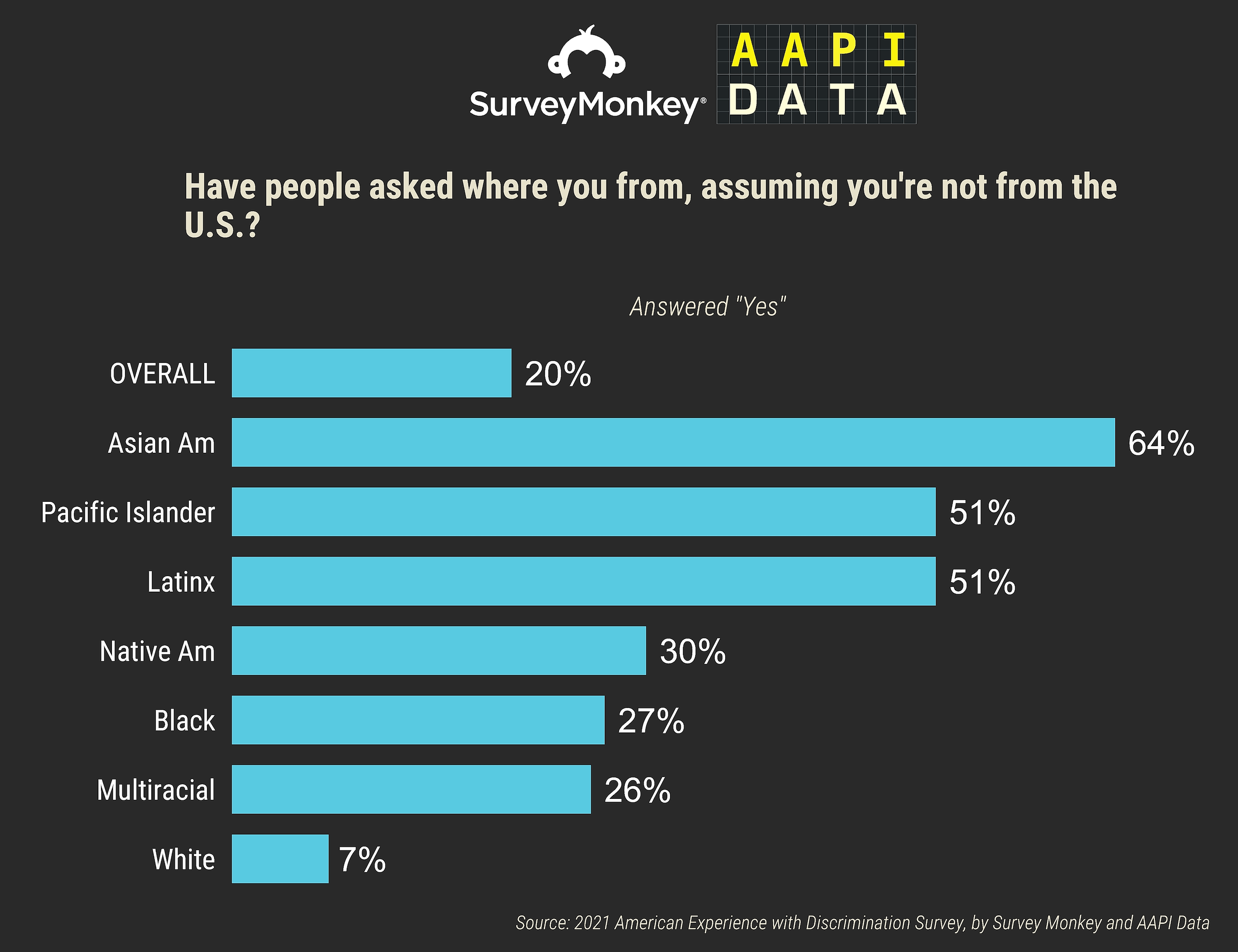

The perceived otherness and foreignness of Asian Americans are reflected in the responses to the survey question inquiring how often they are asked, “Where are you from, assuming you’re not from the US.” Nearly two-thirds of the Asian respondents (64 percent) reported having been asked this question. Asians are 3 times more likely to have been asked this question compared to all survey respondents, and 9 times more likely than White respondents. While seemingly innocuous to an outside observer, the question of where are you from, followed up by where are you really from and where are your parents from, is a reminder that Asians must be from elsewhere, and that they could not possibly be from here.

Ethnicity is not symbolic, costless, recreational, nor optional for Americans of Asian descent the way it is for Americans of European descent, as Mary Waters explains.7 Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 1990More Info → European Americans have the choice of claiming an ethnic identity as Irish, for example, that does not conflict with their national identity as American, yet the perceived foreignness of Asian Americans denies them the parallel privilege.

Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 1990More Info → European Americans have the choice of claiming an ethnic identity as Irish, for example, that does not conflict with their national identity as American, yet the perceived foreignness of Asian Americans denies them the parallel privilege.

So, when Trump referred to the coronavirus as the “Chinese virus,” he vilified a country, its people, and, by extension, Chinese and other Asian Americans whose nativity has always been in question and whose belonging is conditional. Hence, in one fell swoop, Trump put a “bull’s eye” on the backs of Asian Americans, as historian Mae Ngai describes.

On March 16 in Atlanta, our nation’s ugly past of anti-Asian violence, exclusion, and dehumanization became the horrors of our brutal present. To break with the past, we must reckon with our US history and make Asian Americans central to narratives of race in the United States.

Banner photo: Jason Leung/Unsplash.