During the first two years of the Trump administration, the US Congress has voted almost entirely along party lines on most high-profile domestic issues, from the confirmation of Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch, to the repeal of Obamacare, to a major tax overhaul. This pattern conforms to a well-documented, decades-long trend of strong partisan polarization on Capitol Hill.1→Nolan McCarty, Keith T. Poole, and Howard Rosenthal, Polarized America: The Dance of Ideology and Unequal Riches (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006).

→Sean Theriault, Party Polarization in Congress (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

Yet congressional bipartisanship has characterized several important foreign policy debates in the Trump era. Last July, the House and Senate nearly unanimously approved legislation, opposed by President Trump, that imposed new sanctions on Russia and restricted the president’s ability to lift sanctions on that country. More recently, Democratic and Republican lawmakers worked together successfully to preserve the budget for diplomacy and foreign aid after Trump proposed slashing it by one-third. Other current foreign policy debates lack bipartisan consensus in Congress, but nevertheless feature bipartisan coalitions created by intraparty divisions. Examples include efforts to repeal or replace the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) enacted soon after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks; restrict US arms sales to Saudi Arabia based on concerns about the Saudi military’s killing of civilians in Yemen; and limit the president’s ability to place tariffs on imports from other countries.

“Bipartisanship still occurs on a number of key US foreign policy issues, despite the severe overall polarization of US politics.”These examples illustrate two important patterns. First, bipartisanship still occurs on a number of key US foreign policy issues, despite the severe overall polarization of US politics. Second, contemporary foreign policy bipartisanship often deviates from the standard image of bipartisanship, in which the president gains the support of lawmakers in both parties. This political alignment, which I label “classic bipartisanship,” is reflected in the common saying that politics should stop at the water’s edge. But today’s foreign policy debates frequently involve both parties in Congress working together to challenge the president or feature alliances between Democrats and Republicans that are generated by intraparty splits. I call the former alignment “anti-presidential bipartisanship,” and follow other scholars in calling the latter alignment “cross-partisanship.”2Joseph Cooper and Garry Young, “Partisanship, Bipartisanship, and Crosspartisanship in Congress and the New Deal,” in Congress Reconsidered, ed. Lawrence C. Dodd and Bruce I. Oppenheimer, 6th ed. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 1997), 246–273.

Why do we see these multiple forms of bipartisanship in foreign policy, even when US politics is sharply polarized on the whole? My research suggests that three variables—ideology, interest groups, and institutional incentives—help to explain why elected officials align with each other in different ways. These factors illuminate both the persistence of bipartisanship and the diversity of political alignments in foreign policy, which predate Trump and will almost surely continue under his successor.

Frequency of bipartisan alignments in foreign policy

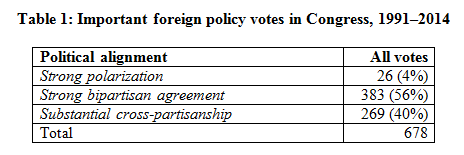

The frequency of multiple bipartisan alignments is illustrated by data I have collected of important congressional foreign policy votes. These data include all 678 foreign policy votes that were highlighted by CQ Almanac (an annual publication that summarizes key congressional activity) between 1991 and 2014. Only 4 percent of these votes were characterized by strong partisan polarization, in which at least 90 percent of Republicans and at least 90 percent of Democrats voted on opposite sides (table 1). On the other hand, 56 percent of the votes were marked by strong bipartisanship, in which at least 90 percent of the members of each party voted together or lawmakers approved legislation by voice vote or unanimous consent.3Congress typically uses voice votes and unanimous consent votes only for legislation with strong bipartisan support.

→Laurel Harbridge, Is Bipartisanship Dead? Policy Agreement and Agenda-Setting in the House of Representatives (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 75.

→David R. Mayhew, Divided We Govern: Party Control, Lawmaking, and Investigations, 1946–2002, 2nd ed. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005), 222. The remaining 40 percent of votes featured substantial cross-partisanship, in which at least 10 percent of the members of a party voted against their party’s dominant position.

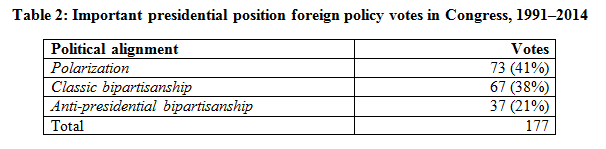

My data further reveal that both classic bipartisanship and anti-presidential bipartisanship are rather common on important foreign policy issues. According to CQ Almanac, the president took a clear public position on 177 of the 678 votes. Of these 177 votes (Table 2), a majority of Republican lawmakers and a majority of Democratic lawmakers voted in support of the president’s position 38 percent of the time, while majorities of both parties voted against the president’s position 21 percent of the time. (In the remaining 41 percent of cases, a majority of Democrats voted on the opposite side as a majority of Republicans.) The instances of classic bipartisanship include legislation funding an expansion in anti-AIDS foreign assistance, approving a nuclear cooperation agreement with India, and backing a trade agreement with South Korea. The cases of anti-presidential bipartisanship include legislation imposing sanctions on Iran, funding weapons systems that the president considered unnecessary, and restricting the president’s ability to transfer detainees from Guantanamo Bay to US prisons.

Although these data certainly do not represent all congressional foreign policy activity, they clearly suggest that severe polarization in this area is not the norm and that alignments featuring different kinds of bipartisanship occur regularly on foreign policy issues.

What we know about polarization and bipartisanship

These patterns are notable in part because many political scientists and journalists see Congress today through the lens of partisan polarization. Indeed, polarization on Capitol Hill has increased dramatically since the 1970s.4McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal, Polarized America; Theriault, Party Polarization in Congress. Scholars have advanced a range of explanations for this phenomenon, with hypothesized drivers ranging from ideological polarization among elites or the public to intensified competition between the two parties over control of Congress.5→Alan I. Abramowitz, The Disappearing Center: Engaged Citizens, Polarization, and American Democracy (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010).

→Hans Noel, Political Ideologies and Political Parties in America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

→Frances E. Lee, Insecure Majorities: Congress and the Perpetual Campaign (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

→Michael Barber and Nolan McCarty, “Causes and Consequences of Polarization,” in Political Negotiation: A Handbook, ed. Jane Mansbridge and Cathie Jo Martin (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2016), 37–89. Increased polarization, in turn, has reduced congressional productivity.6→Sarah A. Binder, “The Dysfunctional Congress,” Annual Review of Political Science 18 (2015): 85–101.

→Barber and McCarty, “Causes and Consequences of Polarization.”

Many, but not all, studies have further found that the trend of rising polarization carries over to foreign policy debates;7Studies finding increased foreign policy polarization include

→C. James DeLaet and James M. Scott, “Treaty-Making and Partisan Politics: Arms Control and the US Senate, 1960–2001,” Foreign Policy Analysis 2, no. 2 (2006): 177–200.

→Charles A. Kupchan and Peter L. Trubowitz, “Dead Center: The Demise of Liberal Internationalism in the United States,” International Security 32, no. 2 (2007): 7–44.

→Frances Lee, Beyond Ideology: Politics, Principles, and Partisanship in the U.S. Senate (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

Studies finding persistent bipartisanship include

→Stephen Chaudoin, Helen V. Milner, and Dustin H. Tingley, “The Center Still Holds: Liberal Internationalism Survives,” International Security 35, no. 1 (2010): 75–94.

→Joshua D. Kertzer, Stephen G. Brooks, and Deborah Jordan Brooks, “Do Partisan Types Stop at the Water’s Edge?” Paper presented at the Princeton IR Colloquium (2017). however, regardless of the trend line, Congress generally is less polarized on international than on domestic issues.8Ashley E. Jochim and Bryan D. Jones, “Issue Politics in a Polarized Congress?” Political Research Quarterly 66, no. 2 (2013): 352–369; Harbridge, Is Bipartisanship Dead? Political scientists have also found that foreign policy bipartisanship is more common when the United States faces a significant international threat, the economy is strong, the two parties are regionally diverse, the views of party elites converge, or the issue at stake involves national security.9→James M. McCormick, and Eugene R. Wittkopf, “At the Water’s Edge: The Effects of Party, Ideology, and Issues on Congressional Foreign Policy Voting, 1947–1988,” American Politics Quarterly 20 (1992): 26–53.

→Mark Souva and David Rohde, “Elite Opinion Differences and Partisanship in Congressional Foreign Policy, 1975–1996,” Political Research Quarterly 60 (2007): 113–23.

→Peter Trubowitz and Nicole Mellow, “Foreign Policy, Bipartisanship and the Paradox of Post-September 11 America,” International Politics 48 (2011): 164–87.

Drivers of bipartisan alignments in foreign policy

But why do we regularly observe several foreign policy alignments, including partisan polarization, classic bipartisanship, cross-partisanship, and anti-presidential bipartisanship, in today’s highly polarized political environment? My ongoing research suggests that ideology, interest groups, and institutional incentives provide a large part of the answer. In what follows, I briefly outline how each of these variables can contribute to different alignments among elected officials.

Ideology

Issues vary in the extent to which they map onto a left-right ideological spectrum. Some policy debates, such as whether to raise taxes, prohibit abortion, or loosen environmental regulations, pit distinct liberal and conservative positions against each other. But other policy debates, such as whether to impose sanctions on a repressive government, support a multilateral agreement to liberalize trade, or use military force to stop a humanitarian catastrophe, lack a clear ideological fault line or feature ideological cross-pressures that can create liberal and conservative bedfellows.

Although liberals generally favor a more cooperative and less militant approach to international affairs than conservatives,10→Eugene R. Wittkopf, Faces of Internationalism: Public Opinion and American Foreign Policy (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1990).

→Peter Hays Gries, The Politics of American Foreign Policy: How Ideology Divides Liberals and Conservatives over Foreign Affairs (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014). left-right ideological divisions are less pervasive on international than on domestic issues.11→Delia Baldassarri and Andrew Gelman, “Partisans without Constraint: Political Polarization and Trends in American Public Opinion,” American Journal of Sociology 114, no. 2 (2008): 408–46.

→Robert S. Erickson, Michael B. MacKuen, and James A. Stimson, The Macro Polity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 196.

→Noel, Political Ideologies and Political Parties in America, 81. This pattern contributes to the persistence of bipartisanship in foreign policy because Republican and Democratic politicians can adopt common positions more easily if they do not fear a future primary challenge due to disloyalty to party orthodoxy.

But variation in the ideological character of debates also helps to explain why foreign policy bipartisanship takes multiple forms. While issues marked by broad agreement among voters or elites are conducive to bipartisan unity on Capitol Hill, ideological cross-pressures often contribute to the emergence of cross-partisanship. For instance, consider debates over whether to intervene militarily to address humanitarian disasters. Liberals tend to want government to help people in need, but tend to oppose a heavy reliance on military power. Conservatives tend to be more comfortable with the use of military power, but tend to oppose expansive government efforts to promote social welfare. The upshot is that elites and voters across the political spectrum may come down either in support of or against humanitarian interventions, facilitating the emergence of competing bipartisan coalitions in Congress. Such cross-partisanship characterized US debates over whether to intervene in the Balkans in the 1990s and in Syria following the outbreak of that country’s civil war. For instance, in a key 2013 Senate Foreign Relations Committee vote on whether to authorize US military action against the Syrian government, seven Democrats and three Republicans lined up against five Republicans and two Democrats.

Interest groups

The interest group landscape also varies considerably across policy issues. In some policy debates, the most influential interest groups maintain strong ties to both political parties. In other debates, the advocacy landscape is split between groups possessing close links to one party and groups tightly connected to the other party. In still other debates, interest groups apply cross-pressures on politicians or simply do not play an important role.

Whereas most major interest groups in domestic affairs have a strong partisan orientation,12→Frank R. Baumgartner, Jeffrey M. Berry, Marie Hojnacki, David C. Kimball, and Beth L. Leech, Lobbying and Policy Change: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

→Michael T. Heaney, “Bridging the Gap between Political Parties and Interest Groups,” in Interest Group Politics, 8th ed., ed. Allan J. Cigler and Burdett A. Loomis (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2012), 194–218.

→David Karol, “Party Activists, Interest Groups, and Polarization in American Politics,” in American Gridlock: The Sources, Character, and Impact of Political Polarization, ed. James A. Thurber and Antoine Yoshinaka (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 68–85. groups that lobby the government on international issues are less one-sided in their party ties on the whole.13Emilie M. Hafner-Burton, Thad Kousser, and David G. Victor, “Lobbying at the Water’s Edge: Corporations and Congressional Foreign Policy Lobbying,” ILAR Working Paper #22 (2015). Groups maintaining strong links to both parties on foreign policy include defense contractors and many ethnic diaspora communities. When such groups engage in intensive advocacy on an issue—for instance, in support of defense spending or on matters concerning Cuba, Israel, or Vietnam—broad bipartisan agreement in Congress often results. By contrast, when party-affiliated groups are pitted against each other—as when pro-Democratic environmental groups line up against pro-Republican business coalitions in debates over environmental regulations—elected officials are usually more polarized.

But foreign policy is also marked by many debates in which the interest group landscape facilitates cross-partisanship. On some issues, politicians within the same party are subject to competing interest group pressures. This is often the case in debates over international trade, in which different economic constituencies frequently push elected officials in multiple directions. On the other hand, there exist some foreign policy debates—for example, the ongoing debate over repealing or replacing the 2001 AUMF—in which powerful advocacy groups are not heavily involved.14→David Karol, Party Position Change in American Politics: Coalition Management (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

→Helen V. Milner and Dustin Tingley, Sailing the Water’s Edge: The Domestic Politics of American Foreign Policy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015). In such debates—as with debates that do not map onto a left-right ideological spectrum—elected officials often have considerable freedom to follow their own compass. In either case, conditions are ripe for the formation of competing bipartisan coalitions.

Institutional incentives

“Since presidents are elected by the entire US population and are held accountable by voters for overall national welfare, they have a strong incentive to promote policies that they expect to advance broad national interests.”An additional factor helps to explain why congressional bipartisanship sometimes coincides with interbranch disagreement. Anti-presidential bipartisanship often occurs because of the distinct incentives of the president and lawmakers. Since presidents are elected by the entire US population and are held accountable by voters for overall national welfare, they have a strong incentive to promote policies that they expect to advance broad national interests.15→Stephen D. Krasner, Defending the National Interest: Raw Materials Investments and U.S. Foreign Policy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978).

→William G. Howell, Saul P. Jackman, and Jon C. Rogowski, The Wartime President: Executive Influence and the Nationalizing Politics of Threat (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013). By contrast, lawmakers are sometimes held accountable by constituents or interest groups for their positions on issues, but are rarely held accountable for the resulting policy outcomes.16→David Mayhew, Congress: The Electoral Connection (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004).

→Frances E. Lee, “Interests, Constituents, and Policy Making,” in The Legislative Branch, eds. Paul Quirk and Sarah A. Binder (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 281–313. Lawmakers therefore have more incentive than the president to adopt positions that reflect their personal values, resonate with voters, or are viewed favorably by important groups, but might carry significant foreign policy costs.

Some of these dynamics have been evident in debates over human rights sanctions. While many lawmakers and voters in both parties believe the United States should penalize foreign governments that violate basic human rights, presidents often worry that such sanctions will reduce the willingness of those governments to cooperate with the United States on other foreign policy priorities. This interbranch difference has resulted in anti-presidential bipartisanship in cases ranging from a 1986 law targeting South Africa’s apartheid government to a 2012 law targeting human rights violators in the Russian government.

The shifting landscape under Trump

Under Trump, anti-presidential bipartisanship has taken on a new flavor. From the presidency of Harry Truman through that of Barack Obama, anti-presidential bipartisanship usually challenged presidential policies that were broadly internationalist. But when the current Congress has united against the president, it has usually done so in an effort to maintain pillars of the US-led international order that Trump has attacked. This was evident last year when the House and Senate passed with a total of just four dissenting votes a resolution reaffirming the US commitment to NATO, after Trump’s sharp criticisms of the security alliance. The congressional effort to block Trump from slashing the budget for diplomacy and foreign aid represents another clear example of this new dynamic.

Such recent legislative efforts have been motivated in large measure by a principled concern shared by key lawmakers in both parties that central elements of Trump’s “America First” agenda are misguided. But anti-presidential bipartisanship under Trump—like earlier anti-presidential bipartisanship—has also been enabled by a favorable ideological and interest group landscape on certain issues. For instance, most Americans support NATO, the alliance is particularly popular among Americans of Central and Eastern European descent, and the institution lacks significant interest group opposition. At the same time, a politically diverse network of business groups, military leaders, and nongovernmental organizations has helped to build bipartisan backing for the diplomacy and foreign aid budget on Capitol Hill.

To be sure, foreign policy debates are not immune from strong partisan pressures, as the House Intelligence Committee’s Russia investigation recently underscored. But Democrats and Republicans are still working together on a range of international issues and in a variety of political constellations. Looking beyond the Trump era, the ideological and interest group landscapes, along with distinct presidential and congressional incentives, will continue to shape the prospects for classic bipartisanship, anti-presidential bipartisanship, and cross-partisanship in US foreign policy.

References:

→Sean Theriault, Party Polarization in Congress (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

→Laurel Harbridge, Is Bipartisanship Dead? Policy Agreement and Agenda-Setting in the House of Representatives (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 75.

→David R. Mayhew, Divided We Govern: Party Control, Lawmaking, and Investigations, 1946–2002, 2nd ed. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005), 222.

→Hans Noel, Political Ideologies and Political Parties in America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

→Frances E. Lee, Insecure Majorities: Congress and the Perpetual Campaign (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

→Michael Barber and Nolan McCarty, “Causes and Consequences of Polarization,” in Political Negotiation: A Handbook, ed. Jane Mansbridge and Cathie Jo Martin (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2016), 37–89.

→Barber and McCarty, “Causes and Consequences of Polarization.”

→C. James DeLaet and James M. Scott, “Treaty-Making and Partisan Politics: Arms Control and the US Senate, 1960–2001,” Foreign Policy Analysis 2, no. 2 (2006): 177–200.

→Charles A. Kupchan and Peter L. Trubowitz, “Dead Center: The Demise of Liberal Internationalism in the United States,” International Security 32, no. 2 (2007): 7–44.

→Frances Lee, Beyond Ideology: Politics, Principles, and Partisanship in the U.S. Senate (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

Studies finding persistent bipartisanship include

→Stephen Chaudoin, Helen V. Milner, and Dustin H. Tingley, “The Center Still Holds: Liberal Internationalism Survives,” International Security 35, no. 1 (2010): 75–94.

→Joshua D. Kertzer, Stephen G. Brooks, and Deborah Jordan Brooks, “Do Partisan Types Stop at the Water’s Edge?” Paper presented at the Princeton IR Colloquium (2017).

→Mark Souva and David Rohde, “Elite Opinion Differences and Partisanship in Congressional Foreign Policy, 1975–1996,” Political Research Quarterly 60 (2007): 113–23.

→Peter Trubowitz and Nicole Mellow, “Foreign Policy, Bipartisanship and the Paradox of Post-September 11 America,” International Politics 48 (2011): 164–87.

→Peter Hays Gries, The Politics of American Foreign Policy: How Ideology Divides Liberals and Conservatives over Foreign Affairs (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014).

→Robert S. Erickson, Michael B. MacKuen, and James A. Stimson, The Macro Polity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 196.

→Noel, Political Ideologies and Political Parties in America, 81.

→Michael T. Heaney, “Bridging the Gap between Political Parties and Interest Groups,” in Interest Group Politics, 8th ed., ed. Allan J. Cigler and Burdett A. Loomis (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2012), 194–218.

→David Karol, “Party Activists, Interest Groups, and Polarization in American Politics,” in American Gridlock: The Sources, Character, and Impact of Political Polarization, ed. James A. Thurber and Antoine Yoshinaka (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 68–85.

→Helen V. Milner and Dustin Tingley, Sailing the Water’s Edge: The Domestic Politics of American Foreign Policy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015).

→William G. Howell, Saul P. Jackman, and Jon C. Rogowski, The Wartime President: Executive Influence and the Nationalizing Politics of Threat (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

→Frances E. Lee, “Interests, Constituents, and Policy Making,” in The Legislative Branch, eds. Paul Quirk and Sarah A. Binder (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 281–313.

Comments are closed.