In the late 1980s, the Council launched a new program focused on urban poverty in the United States. The Council's program on the Urban Underclass brought together a wide range of disciplinary expertise, and focused on understanding the connections between macroeconomic change, deindustrialization, neighborhood attributes and processes, and individual and family outcomes. In the first of several Items features on the program, its leading staff―Martha Gephart and Robert Pearson―describe its origins and rationale.

social class

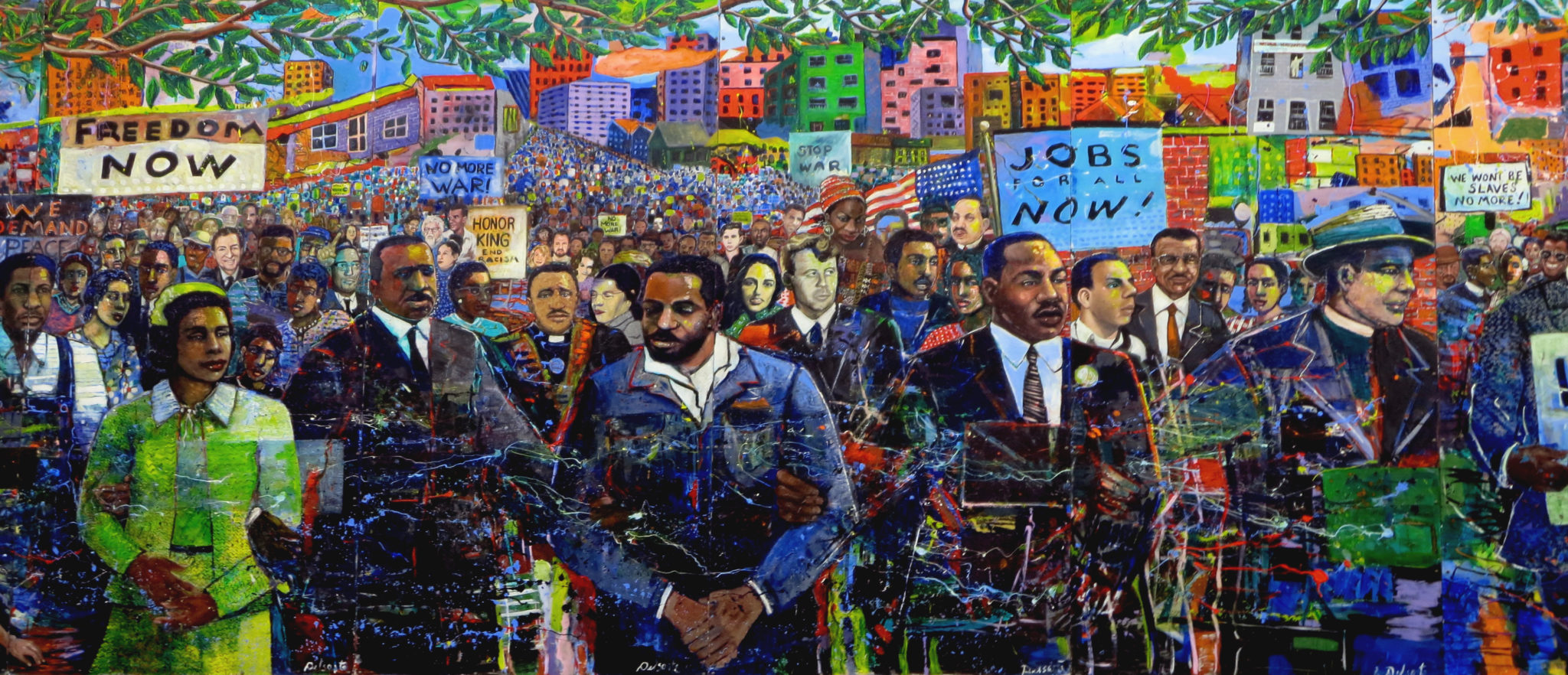

Black and Woke in Capitalist America: Revisiting Robert Allen’s Black Awakening… for New Times’ Sake

by N. D. B. ConnollyIn a new contribution to the "Reading Racial Conflict" series, N. D. B. Connolly analyzes an early gathering of black supporters in the new Trump administration, and much more about the contemporary political economy of race, through Robert Allen’s 1969 Black Awakening in Capitalist America. Drawing on Allen, Connolly makes a strong case for the relevance of (neo)colonialism—and its emphasis on both violence and the co-opting of sections of the elite among the “colonized”—as an essential framework for understanding America’s present.

Ida B. Wells and the Economics of Racial Violence

by Megan Ming FrancisIn the latest essay in our "Reading Racial Conflict" series, Megan Ming Francis draws attention to the extraordinary work of Ida B. Wells. In the late nineteenth century, Wells exposed the extent of racial violence in the United States by documenting lynching and then disseminating her findings through her books, journalism, and activism. Ming Francis emphasizes a further innovation by Wells—i.e., how she connected lynchings to the economic interests and status anxieties of white southerners, as well as the relevance of this connection to understanding contemporary racial conflicts.

Studying Inequality in American Cities

by Items EditorsThis 1992 piece by Alice O'Connor from the Items archive describes a major research effort to document, explain, and compare urban inequality across four American cities: Atlanta, Boston, Detroit, and Los Angeles. The Council’s Committee for Research on the Urban Underclass played a formative role in the early stages of the project, which then went on to publish an influential and prescient volume with the Russell Sage Foundation entitled Urban Inequality: Evidence from Four Cities, which O’Connor, a one-time Council program director, coedited.

Capitalism, Democracy, and Du Bois’s Two Proletariats

by J. Phillip ThompsonJ. Phillip Thompson’s contribution to the "Reading Racial Conflict" series reflects on the concept of the two proletariats developed by W. E. B. Du Bois in his Black Reconstruction. Du Bois’s notion of a working class bifurcated along racial lines, Thompson argues, is critical for understandings of American capitalism and democracy. Thompson sees movements for racial justice as central to addressing inequalities, no less so than those directly claiming to represent the working class, which have historically tended to exclude black workers.

Normative Individualism and Research on Inequality

by Maximilian KasyMaximilian Kasy’s contribution to the “What is Inequality?” series adopts a perspective of “normative individualism,” which considers overall social welfare through the lens of individual welfare and acknowledges that policy changes inevitably create winners and losers in terms of inequality. Drawing from his open online textbook on inequality, Kasy encourages attention to welfare weights that reveal “how much social welfare changes when we change individual welfare,” particularly as different individuals affect the aggregate differently, and argues that egalitarian outcomes emerge when greater weight is given to the poor in the policymaking that shapes wealth distribution.

Why Inequality Matters: The Lessons of Brexit

by Mike Savage and Niall CunninghamMike Savage and Niall Cunningham demonstrate how a focus on inequality can deepen understanding of major political events through their analysis of the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom. Pairing the results of their Great British Class Survey with the geography of support for Brexit, and using data visualization tools, the authors show how the UK regions that voted for Brexit (and the anti-elite sentiment behind it) are also those areas most affected by growing inequalities, social and cultural, as well as economic.

Are We Having the Right Discussion about Inequality in the Twenty-First Century?

by Kevin LeichtIn this contribution to the "What Is Inequality?" series, Kevin Leicht argues strongly that, given the nature and extent of economic inequality in the United States today, scholars and policymakers should address it directly rather than emphasize its social and educational dimensions. Leicht claims that research and public discourse on gaps between identity groups, and on the importance of education for social mobility, distracts attention from the deepening economic differentiation within groups and the need to address broader issues of labor market outcomes and wages.

For an Empirical Sociology of the Future

by Herbert J. GansMotivated by concerns over the problems and tensions of the present, Herbert Gans makes the case for the study of the future—that is, how individuals and institutions imagine and construct future lives and worlds. Understanding future constructions, and their differences across the boundaries of class, gender, race, generation, religion, and other social markers, provides a window into conflicts of the present and new possibilities for engaging them.

Do Disciplinary Boundaries Keep Us from Asking the Right Questions about Inequality?

by David B. Grusky and Kim A. WeedenIn a contribution relevant to both our features on inequality and interdisciplinarity, Kim Weeden and David Grusky examine how tendencies to analyze inequality within disciplinary frames may make it difficult to address key questions about the forms that inequality takes across societies. The authors, who direct centers on inequality at Cornell and Stanford, respectively, focus principally on the assumptions and measurement strategies of economics and sociology and provide suggestions on how these fields can collaborate to provide a deeper understanding of how inequality is structured and how it changes.