The outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic has posed new challenges to how labor is valued (attributed value to) and valorized (extracted surplus from) in advanced capitalist societies. With governments across the world implementing national lockdowns to control the spread of the virus, low-paid low-status work has come to the forefront of public attention as “essential” labor. Glorifying accounts presenting “key workers” as national heroes have faced a reality in which too often migrant workers occupy frontline positions, poorly recognized and remunerated as “low-skilled” work. Migrants enter or remain in such high-risk jobs—both during and outside major crises—not as a choice but out of necessity to avoid extreme forms of precarity and vulnerability vis-à-vis hostile border and labor regimes. The pandemic, thus, makes necessary an urgent discussion on the link between migration and essential work.

To initiate such a discussion, this project—sponsored by the SSRC’s Covid-19 Rapid-Response Grant and the Wenner-Gren Foundation’s Global Initiative fund—focused on a particular case of migrant workers that encapsulates some key contradictions that the pandemic crystalized: Venezuelan migrants in Argentina. Since 2014, over 3,500,000 Venezuelans have migrated across South America. A humanitarian crisis, comparable to the Syrian migrant crisis, the situation of many Venezuelan migrants throughout the continent was severely exacerbated by the pandemic; many were deprived of the means to make ends meet while stuck behind closed borders away from their families or opportunities further afield. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, Argentina received over 150,000 Venezuelans. Unlike other migrants—albeit not unlike Ukrainians fleeing across Europe as of this writing—Venezuelans were touted as “university-educated,” “deserving,” “high-skilled” workers. In an anticommunist trope, they were seen as forsaking an authoritarian socialist regime. They were given a right to residency and work via the Mercosur union. They were initially promised gainful employment in their respective, highly qualified fields.1Gabriela Sala, Ingenieros venezolanos residentes en Argentina (Buenos Aires: Organización Internacional para las Migraciones, 2019). Yet, the recession and political crisis left many unemployed over significant periods of time or working in the informal and gig economy,2→Sala, Ingenieros venezolanos.

→Diego Chaves-González and Carlos Echeverría-Estrada, Venezuelan Migrants and Refugees in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Regional Profile (Washington DC and Panama City: Migration Policy Institute and International Organization for Migration, 2020). in sectors seen as “essential” during the pandemic.

Against this background, our project asked how high-skilled Venezuelans experienced working on the frontline of the pandemic: Did it change/reinforce their perception of “skill,” “risk,” and “reward” in relation to essential work; and how did it relate to the professional class’s sense of entitlement to integration into a welfare system and society at large? To address these questions, we conducted mixed-method research, triangulating the results of 20 online semistructured interviews with an online survey among Venezuelans in Argentina. The online survey used a purposive sampling, based on quotas of gender, educational level, and type of employment. The online fieldwork was carried out between April 8–25, 2021. The total sample consisted of 229 cases. We inquired into their motivations to migrate, choice of country, ways of travel and job search, formal and informal support organizations, labor and social integration before and during the pandemic outbreak, as well as for their future prospects.

Re/defining our sample: Social texture of Venezuelan migration to Argentina

With few exceptions during dictatorships and recession, Argentina has historically been a country that receives migrants, but so has Venezuela. Yet, the geographical distance between the two countries, and their position within different regions of Latin America—the more affluent South Cone featuring the countries with the highest GDP on the subcontinent, and the much less economically prosperous South American Caribbean coast—have meant they have also been positioned differently in the nomenclature of countries in terms of standards of living and access to public welfare. This has made Argentina a desirable but also difficult destination for many Venezuelans. Traveling by land, the vast majority of the Venezuelan migrants—at one point in the crisis leaving at the rate of 5,000 people a day3Sala, Ingenieros venezolanos, 13.—stayed in bordering countries like Colombia and Brazil or combined bus journeys and, more rarely, shorter plane travel to reach further destinations along the Andean route.

As a recent study commissioned by the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) and International Organization for Migration (IOM) has shown,4Chaves-González & Echeverría-Estrada, Venezuelan Migrants and Refugees. this has created a polarization especially visible between the migrants who arrived in Colombia (1.4 million) and those who landed in Argentina. While the majority of the Venezuelan migrants in Colombia had significant financial constraints (over 90 percent) and/or rarely had a technical or university degree (only 15 percent), those who arrived in Argentina by 2019 were mostly educated to a higher education or technical college level (70 percent), rarely declared economic hardship (14 percent), and mostly arrived by air (75 percent).5Chaves-González & Echeverría-Estrada, Venezuelan Migrants and Refugees, 6, 9. Yet, despite the fact that over 50 percent of Venezuelans in Argentina were either already in possession of Argentine citizenship or were about to receive residency, over 70 percent of Venezuelans worked in the informal economy and over 50 percent declared their work riskier than back in Venezuela.6Chaves-González & Echeverría-Estrada, Venezuelan Migrants and Refugees, 15, 22.

The MPI/IOM and other existing surveys of Venezuelan migrants in Argentina—which increased exponentially during the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic in fall 2020—were both a convenience and a challenge for us. Especially the MPI/IOM survey, conducted among a larger population unit than our scoping survey, was useful in designing our interview sample. We aimed to be representative according to education level, residence status, employment status, and gender, with just around 60 percent women and 40 percent men respondents. Among these, we were looking specifically for essential workers in spheres designated by the Argentinian government as such, and to which migrant workers could be recruited. Yet, the plethora of surveys emerging at the same time also may have led to survey fatigue among the target population that made us reverse the initially planned sequence of survey and interviews. This allowed us to draw themes from the interviews to inform the survey, rather than the opposite. It also meant that having established rapport, we could ask our research participants to take the survey and distribute it in their network.

Findings: Thin red lines between free market, welfare security, and class

Our survey and interview findings challenged the perception of Venezuelan migrants in Argentina’s unitary representation as more “high-skilled.” As stated earlier, data, featured in earlier surveys,7Chaves-González and Echeverría-Estrada, Venezuelan Migrants and Refugees. had shown that unlike in other countries closer to Venezuela, the Venezuelan migrants in Argentina mostly had superior technical or university education. In our research, we found and reported an internal fragmentation of this group along three trajectories, which varied according to how they faced the pandemic, and how they felt “essential work” was valued/valorized.8Jésica Lorena Pla and Mariya Ivancheva, “Redefiniendo el ‘trabajo esencial’ Covid-19 y migración venezolana en Argentina” in Boletín #6 (Trans)Fronteriza: Cuando los cuidados interpelan las fronteras, eds. Héctor Parra García, Carlos Alberto González Zepeda, and Maeriela Paula Díaz (Buenos Aires: CLACSO, 2021), 60–67. A first small category of professionals managed to keep working in their field of expertise. That gave them a positive (but distant) view of how society at-large valued and rewarded essential work. A second larger group, who had initially gotten office and technical jobs similar to those they held in Venezuela, often lost employment during the pandemic, but could rely on savings, property, social networks, and welfare, “affording” periods of unemployment to avoid risky jobs. A third large category of workers, including those employed in the platform economy,9“Platform economy” refers to economic and/or social exchanges facilitated by online platforms, such as food delivery or taxi service applications. had no financial or social capital to fall back on, and kept working to keep afloat. They experienced first-hand how essential work was poorly valued and rewarded and saw their labor rights and access to public welfare reduced.

“Not me, but other Venezuelans had to go out and do the shopping and delivery for Argentinians…the logic: ‘Go out and get ill, so I don’t get ill.’ It was similar with all essential workers, as in health they just got some claps, but no recognition…”

—C., male, 33, freelance journalist.

“Here I found a job in my field, but when the pandemic started, they asked me to work from home with my own device and paid very little so I quit. […] I am now looking for jobs and living on my savings […]”

—J., female, 38, ex-trade worker, now unemployed, single mother.

“Customers would spray chlorine into my eye, ‘Look, I know you’re afraid, but I’ll go blind!’ If their food is late, it’s never the restaurant’s fault, it’s always my ‘meandering’.”

—S., female, 32, ex-call center, now delivery.

“I was working as a technician but once the pandemic came, I had no other choice, as my employer stopped calling me in. I started working for a platform. This platform previously offered legal work (trabajo en blanco) but now would fire regular workers and employ them informally (trabajo en negro).”

—S., male, 50, ex-technician, now taxi app driver.

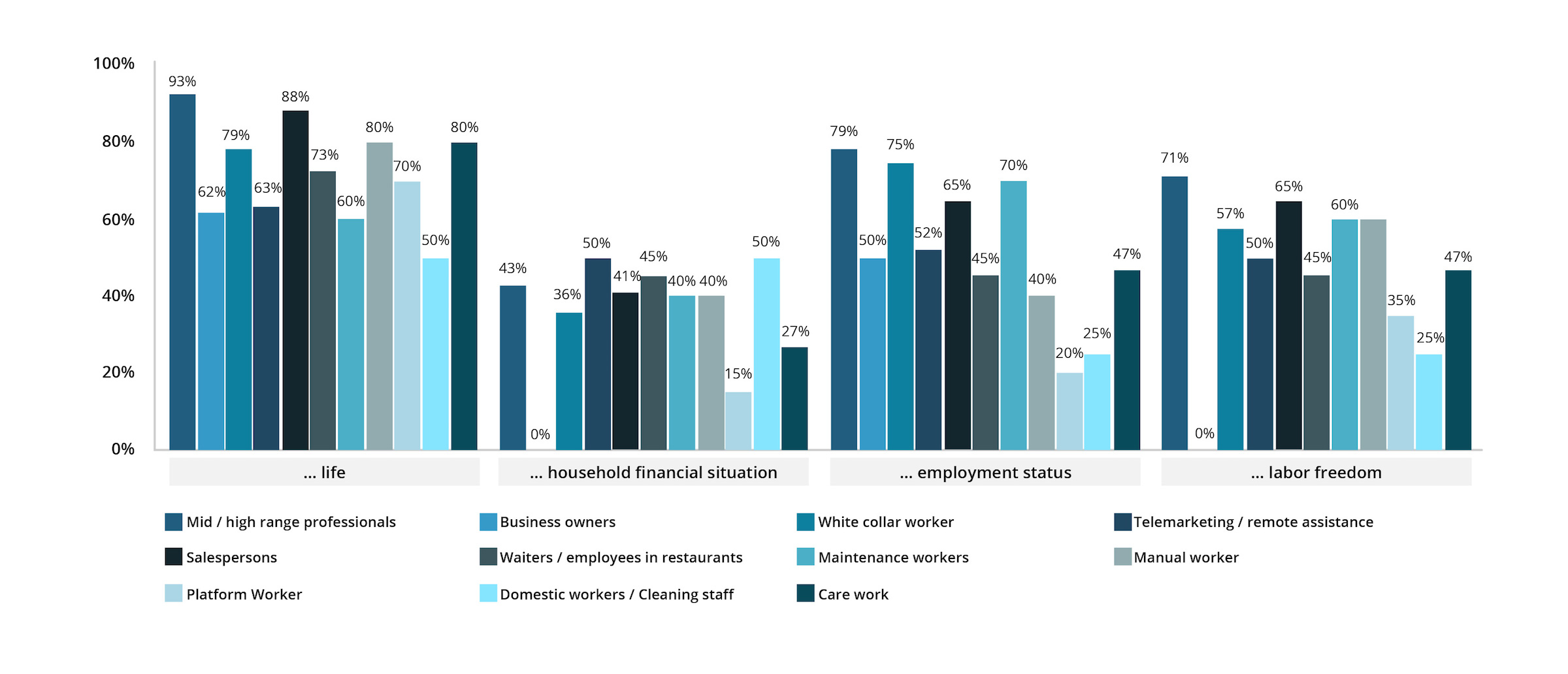

This fragmentation is visible in the aspects of our findings related to perceptions of economic in/justice and work and life dis/satisfaction (see Graph 1), and it is less visible when it comes to political views (see next paragraph). On the first points, among those who self-described as essential workers across different categories, we found that mid- and high-range professionals working in their corresponding field, those in white-collar jobs, and salespeople kept the highest sense of satisfaction with their life (93 percent, 79 percent, and 88 percent, respectively), employment status (79 percent, 75 percent, and 65 percent, respectively), and autonomy at work (71 percent, 57 percent, and 65 percent, respectively), but were relatively unsatisfied with the financial situation of their household (43 percent, 36 percent, and 41 percent, respectively).

This was not the case among small business owners, who were among those least satisfied with their life (62 percent), moderately satisfied with their (self)employment status, but their satisfaction with the financial situation of their household and their autonomy was at 0 percent as many lost their businesses and were dependent on savings to survive.

Beyond them, especially in some male dominated “key” sectors, such as platform work, essential workers’ experiences revealed that they felt undervalued, exposed to significant risk at work, and dissatisfied with their work freedom (65 percent), employment status (80 percent), and income (85 percent), but were relatively satisfied with their life in general (70 percent). As other studies had shown, migrants working in the gig economy were also those who worked the most hours (48–58 hours per week),10Javier Madariaga et al., Economía de plataformas y empleo ¿Cómo es trabajar para una app en Argentina? (Buenos Aires: CIPPEC, BID & OIT, 2019), 105. and their primary income stemmed from this work alone (85-95 percent). In other sectors where the workforce is predominantly composed of women, such as domestic work, the sense of freedom and satisfaction at work were lower (25 percent on both counts), the experience of financial control was higher (50 percent), but life satisfaction is much lower (50 percent). To summarize, the characteristics of occupational position influence the perception migrants have on the value of social solidarity and integration, but also about their integration and satisfaction with it in the receiving country.

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

On the second point about political behavior, we encountered quite a unified position that most Venezuelans shared regardless of their occupation or financial situation. Their views, defined by their experience in Venezuela and opposition media narrative about the country’s crisis, seemed to have decisively colored their opinions of left-wing governments and institutions in general. However, somewhat paradoxically, they appreciated Argentina’s public services and social welfare programs, despite their pronounced fear of the return of socialism. The latter was a mixture of fantastical anecdotes of socialism in Cuba and experiences of its Bolivarian variation in Venezuela, which lead them to categorize it as evil, contagious, and creeping ever closer to Argentina. This phenomenon was envisaged and feared after the 2019 return of Peronismo following the electoral victory of the rather moderate Alberto Fernández.

Escaping political alienation under a left-wing regime, many Venezuelans came to the “postpopulist” Argentina of former President Mauricio Macri in search of a free-market economy and feared the return of Peronism. Landing in recession-struck Argentina with a skyrocketing inflation and growing unemployment,11Sala, Ingenieros venezolanos, 20. the majority had to enter low-skilled jobs in the informal and gig economy of the capital Buenos Aires.12Madariaga et al., Economía de plataformas y empleo. Yet, when deciding to migrate to and remain in Argentina, most of our interviewees stated explicitly that the country was attractive due to its access to public health and generous education and social welfare benefits, from which some benefited during the Covid-19 pandemic. This public infrastructure, however, was an inseparable part of Peronist reforms of the past, and it’s more recent governments under the late Néstor Kirchner and former president and now Vice President Kristina Fernández de Kirchner. These governments have been part of the so-called progressive cycle or Pink Tide in Latin America of which Hugo Chavez’s democratic socialism of the twenty-first century, later inherited by Nicolás Maduro, have also been included, despite their different approaches to reform.

“I came here just while I’m waiting for Maduro to leave, I don’t want to live in a dictatorship. … In Venezuela we had no access to medicines, antibiotics, anesthetics, you had to buy them on the black market at their dollar price… Here, I can get prescriptions from the public healthcare and sent to relatives in Venezuela…”

—S., female, 61, former lawyer, now does elderly care.

“I wouldn’t go back to Venezuela; I want my son to get a good public education.”

—J., female, 38, ex-commercial worker, now unemployed, single mother.

“Socialism is a virus killing Argentina.”

—L., male, 35, ex-professional sports teacher, delivery.

Concluding remarks

As our survey only took place in April 2021 and the results are still to be analyzed in greater depth, this essay presents a snapshot of tentative results. Although this research was conducted almost a year ago, it ironically could also speak to a new wave of mass migration and forced displacement: the mass exodus of Ukrainians into Eastern and Western European countries. Similarly branded as “deserving” and “educated” migrants, unlike previous waves of from Syria, Afghanistan, and other Global South migrants, it is a big question if and how the perception of this migrant wave will change, and what welcome would they receive on the European job market, where Ukrainians have traditionally occupied low-skilled jobs.13Olga Kupets, “Economic Aspects of Ukrainian Migration to EU Countries,” in Ukrainian Migration to the European Union, eds. Olena Fedyuk and Marta Kindler (Springer, 2016), 35–50. In the case of Venezuelans, triangulating the survey results with the interview findings, we show that the Venezuelan migration to Argentina is already quite varied in terms of socioeconomic backgrounds, experiences, and strategies of survival during the pandemic, and we do not predict this tendency changing. While all migrants are relatively satisfied with their life, essential workers, especially in the platform and domestic work sectors, are exposed to greater risk but also see lower levels of economic stability and labor autonomy. What unifies most research participants, however, is a somewhat paradoxical distaste for socialism but desire for access to welfare institutions and services.

References:

→Diego Chaves-González and Carlos Echeverría-Estrada, Venezuelan Migrants and Refugees in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Regional Profile (Washington DC and Panama City: Migration Policy Institute and International Organization for Migration, 2020).